Back again, this time as a MOD DVD-R from Warner Archive.

A couple of generations didn’t get to grow up on Broadway Bill as we had other Capra classics such as It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) or It’s a Wonderful Hor Life (1946), but not long after Capra’s 1991 death at age 94 we youngsters were treated to a theatrical re-release of Broadway Bill, unseen beyond rare museum screenings since at least the time of Capra’s own 1950 remake, Riding High starring Bing Crosby. While Broadway Bill doesn’t rank as high as those classics named above or Capra’s pair starring Gary Cooper, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and Meet John Doe (1941), I’d include it among what I consider the director’s more middling creations of the period, titles such as Lady for a Day (1933) or You Can’t Take it With You (1938). While Broadway Bill did not quite receive the critical fanfare of those titles, it fared better with its contemporary audiences than it does with modern crowds. It is not a timeless classic like Capra’s best films, but a slightly dated, better-than-average movie more suited to fans of the oldies than a general audience today.

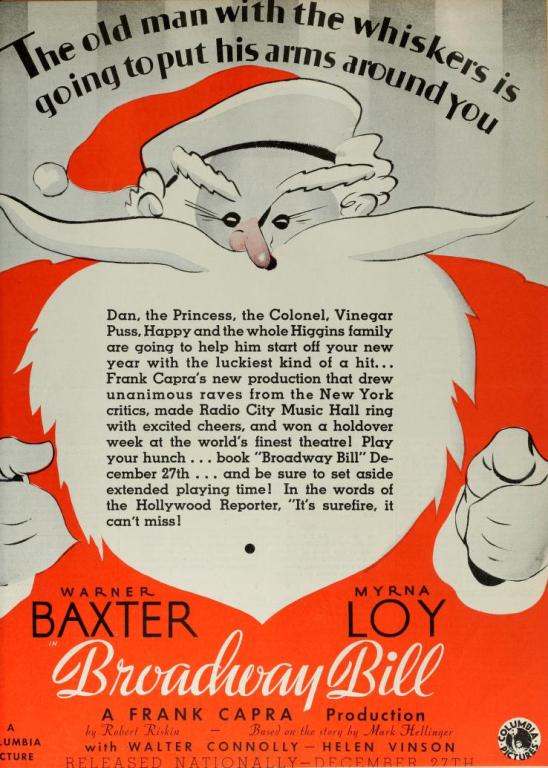

Two page trade ad from Film Daily, November 16, 1934 issue. All Film Daily ads on this page found through the Lantern search engine.

It still beats Riding High, the 1950 version made by Capra for Paramount that tosses in a few Crosby tunes with heaps of recycled footage and many familiar faces, some aged as they reprise their roles, others, thanks to that recycling, looking no older than they had in 1934 (Hello, Clara Blandick!).

Above: Scene from Riding High shows star Bing Crosby with four returnees from Broadway Bill: Clarence Muse to the left of Bing; Ward Bond, Douglass Dumbrille and Charles Lane to the right.

To remake the movie in 1950 Capra had to swing a deal with his old Columbia boss Harry Cohn that resulted in the original film and its rights transferring from Columbia to Paramount. Capra could then proceed with his remake, but Paramount kept the original movie under wraps to prevent it from eating into profits of the new version starring Crosby and Coleen Gray. Beyond any issues of rights there also turned out to be issues with the original film negative leaving us to speculate over 21 missing minutes of Broadway Bill to this day. Any murky issues of availability are now long settled and since shortly after the time of its 1992 theatrical re-release Broadway Bill has been available to the general public on home video in a variety of formats over the years. It has most recently been released by Warner Archive as a Made-on-Demand DVD-R that I requested for review.

Broadway Bill is not so much about a man and a horse, or even a man and a woman, as it is about that man seeking his independence. The horse is a tool towards that goal. This is the movie known for including Capra’s first mention of the “little fellas,” using its everyman lead character, here Warner Baxter as Dan Brooks, to damn his wealthy father-in-law for gobbling up people and their dreams simply for the sake of accumulating money. In that theme fans of the more standard Capra classics will find familiar ground in Broadway Bill.

Free spirit Dan Brooks (Baxter) has somehow married into the richest family in Higginsville, the Higgins family, of course. Patriarch J.L. Higgins (Walter Connolly) presides over the town bank and has installed each of his sons-in-law in charge of various other family holdings: One heads the Higgins Iron Works, another the Higgins Lamp Shade Company and J.L. has only just acquired the Acme Lumber Company with intentions of it one day being run by the man who’s to sit in the empty chair across from youngest daughter, Alice (Myrna Loy). Dan was installed as head of the Higgins Paper Box Company when he married eldest daughter, Margaret (Helen Vinson). He did well by the company for a couple of years, but J.L. holds a family meeting to expose its decline and blame Dan for being distracted from the business of paper boxes because of his involvement with his racehorse, Broadway Bill. J.L. insists Dan give up horses.

After a moment of pained thought Dan rebels. “Everything here seems lopsided to me,” he says in protest before invoking the “little fellas” and accusing J.L. of eating up people and their life’s ambition for no other reason than to grow his own empire. When Dan rises from his chair and opts out of Higginsville young Alice applauds him but his wife, Margaret, refuses to join him on his journey. Dan leaves Higginsville with the clothes on his back, Broadway Bill and his trainer, Whitey (Clarence Muse), alongside him.Broadway Bill stands for Dan’s independence from the paper box factory, Higgins money and Higgins influence. Dan’s ultimate goal is not simply success for Broadway Bill, but to pyramid Bill’s winning purses towards his own horse empire, training them, perhaps even breeding them, in order to return to Higginsville one day and reclaim his wife from a position of respectability. Dan has to scrimp, save and scam every dollar he can grab in order to run Bill at the track and eventually pay for his place in the Imperial Derby. Along the way he’s joined not by his wife, but her little sister, Alice, who Dan affectionately calls “The Princess.” The Princess is in a tough spot emotionally as she carries a torch for her brother-in-law and so aligns every bit of her heart with Dan’s goals, while trying not to make her deeper feelings more obvious to him.

Dan’s racehorse is a lot like him, a bit of a bad penny who has the tools for victory but is a bit too stubborn for it to come easy. His time around the track continues to improve, but Bill rebels at the start of a practice run intended to boost Dan’s kitty towards the Derby entry fee. Broadway Bill refuses to be loaded into the starting gate and protests by tossing his jockey to the ground.Broadway Bill, more than Baxter’s Dan, winds up becoming “friend of the downtrodden,” as Dan’s partner Colonel Pettigrew (Raymond Walburn) refers to him on race day. This occurs after another wealthy magnate, J.P. Chase (Claude Gillingwater), inadvertently turns Dan’s personal tool for independence into a bastion of hope for all those feeling the Great Depression. The rich man is restless in his hospital bed and begs his nurse to tell him what she does to keep herself distracted in such a place. She tells him that she runs with the angels and explains that she’s just put a two-dollar bet on hundred-to-one long shot Broadway Bill. When Chase asks her to wager two smackers for him the nurse is so amused that she jokes about it with her co-workers. What follows is a great Capra scene where Chase’s two-dollar bet grows as the gossip passes from one hopeful bettor to another (including Lucy’s switchboard operator). So many two dollar bets flood the track from Capra’s “little fellas” that Bill’s odds drop, first to sixty-to-one and eventually all the way down to six-to-one, while the odds grow longer on formerly favored horses.

“Sucker money,” Eddie Morgan (Douglass Dumbrille) explains to his co-conspirators as he waits for odds on his partner’s horse, Sun Up, to drop before unleashing a hundred thousand dollars into the Derby’s now crooked gambling coffers. Morgan has already paid off the jockey riding favorite Gallant Lady and will eventually saddle his own jockey onto Broadway Bill as well, but first he has to get hot-tempered Dan Brooks out of jail and out of hock in order for Bill to run. Morgan explains that he has a stake in seeing Bill run and Dan is thankful that his “old man with the whiskers” has finally shown up to clear the path for Broadway Bill to the finish line.

Above: Another Film Daily ad readies film exhibitors for the coming holiday release of Broadway Bill. From the December 11, 1934 issue. A few days earlier Film Daily published suggested ballyhoo for Broadway Bill centered on the “old man with the whiskers” angle. Each of the gimmicks involved putting Santa Claus in store windows or out on the streets to pitch the movie.

What follows is not the expected feel good ending nor is it the original ending from the screenplay by regular Capra collaborator Robert Riskin. The Riskin script had been adapted from an unpublished story, “On the Nose,” by Mark Hellinger. It was while filming on location at the Tanforan Race Track near San Francisco that Capra realized he needed a better ending to make Broadway Bill anything more than a routine follow-up to his most recent film, It Happened One Night. Riskin was on vacation at this time leading to eventual controversy over who came up with the revised ending to Broadway Bill, but whatever the case it certainly is more memorable than what was originally intended.

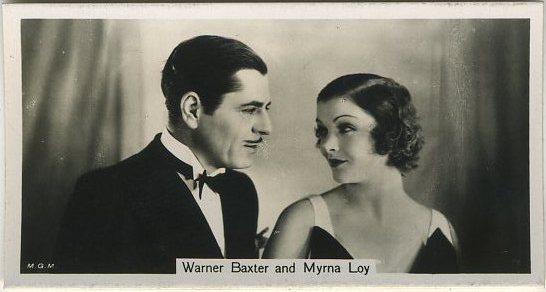

Frank Capra had received his first Academy Award nomination for Best Director earlier that year for his screen adaptation of Damon Runyon’s Lady for a Day in 1933. By the time of Broadway Bill additional praise was being heaped upon Capra for It Happened One Night, the film which would capture the first of his three Oscars. He had originally planned the starring role of Broadway Bill for Clark Gable, but ironically after Gable’s success on loan to Columbia for It Happened One Night, MGM refused to lend him again. The eventual selection of Warner Baxter leads to very little comment from Capra over the years other than his disappointment over the actor’s fear of horses. I may be a biased Baxter fan, but this isn’t something I noticed watching the movie as I found the star acting natural and warmly towards Broadway Bill. Myrna Loy, who had previously refused the Claudette Colbert part in It Happened One Night, jumped at a second opportunity to work with Capra. It was a good year for Loy who MGM began teaming with William Powell in films such as Manhattan Melodrama and The Thin Man.

Myrna Loy was a star on the rise while Warner Baxter at the time, already with his Oscar on the mantel, was one of Fox’s top stars and biggest earners. Baxter and Loy had previously co-starred in Renegades (1930) for Fox and, possibly their best remembered film together, Penthouse (1933) at MGM. They would be teamed together once more for To Mary – with Love at Twentieth Century-Fox in 1936.

There would be a growth in the number of movies about horse racing throughout the 1930s as the Sport of Kings regained many fans throughout one of its most exciting decades. The lift of a ban on parimutuel betting brought regular races back to Tanforan Racetrack in 1933 and that would be where Capra filmed the racing scenes in Broadway Bill and later return for Riding High. That same year saw a bit of notoriety and excitement inside the sport when Brokers Tip beat Head Play by a nose in the Kentucky Derby’s famed “fighting finish.” While Broadway Bill had its premiere in New York on Thanksgiving Day, 1934, by the time it was put into general release Hollywood had grown even more excited about the races with the opening of the Santa Anita racetrack near Los Angeles that Christmas Day. Broadway Bill opened in San Francisco, home of Tanforan, and nationwide, just two days later, December 27, 1934. It was a true holiday release and based on some of the trade ads on this page seems to have broke out of the gates to strong business. Capra biographer Joseph McBride wrote that Broadway Bill was “only a modest commercial success” (319).

Both Broadway Bill and Riding High have been criticized for it’s treatment of African-American actor Clarence Muse as Dan’s whipping boy, Whitey. While Dan’s treatment of Whitey will sit poorly with modern viewers it may be worth noting that in the earlier movie Dan is just as quick to take a kick at the backside of two other characters who are both white. Each of those men also rank lower in society than Dan and so some of the worst moments with Muse actually look worse in the vacuum of a short clip than they play in the movie as a whole. What are usually thought of as some of the film’s more racist moments may in fact be a more general misplaced notion of superiority held by our supposedly everyman hero. It’s not nice to kick anyone in the ass, regardless of color. That said, Whitey is most definitely Dan’s subordinate and treated as such throughout. By the same token, Broadway Bill probably is no more overtly racist than any other film of the period featuring a black actor in such a memorable supporting role. As usual Muse holds his own in Broadway Bill and his Whitey turns out to be as important as any other character in the movie except those played by leads Baxter and Loy.

Warner Baxter is excellent as Dan Brooks, the greatest sin in his performance being that he simply is not Clark Gable. Broadway Bill was never going to be It Happened One Night, despite Walter Connolly’s presence in each. Baxter’s Dan Brooks is a little obnoxious at times but that appears to be by design and Baxter’s version is slightly less abrasive than Bing Crosby’s later portrayal. Myrna Loy shines as the suffering Princess and shares several strong scenes with Baxter. Many from the supporting cast, most notably Muse, would be brought back by Capra in 1950 for Riding High, including Raymond Walburn, Margaret Hamilton, Frankie Darro, Douglass Dumbrille, Charles Lane and Ward Bond. Besides reusing the Clara Blandick footage mentioned above, Capra also repurposes all of the original horse racing scenes, scenes with Gallant Lady’s trainer (that actor, Forrester Harvey, had died in 1945), and several bits of original footage of the Dumbrille, Lane and Bond trio, who also appear in new footage sixteen years older! One notable addition to the Riding High cast was Oliver Hardy, who plays the Colonel’s pawn in the racetrack scam originally enacted by Harry Holman in Broadway Bill.

Above: Raymond Walburn and Margaret Hamilton are off to the races in Broadway Bill. Lynne Overman in background at right in a part that would be taken over by William Demarest in the 1950 remake Riding High.

Highlights of Broadway Bill include the mania produced by J.P. Chase’s two-dollar bet; Walburn being bilked by his own chicanery after his Doughboy tip to Harry Holman’s racetrack sucker; and, of course, the tension surrounding the Imperial Derby itself. Smaller bits of pleasure are derived from several of Loy’s scenes including one with Connolly where the father realizes his daughter is in love with her sister’s husband and scenes shared with Baxter such as when he innocently tries to take back his pants from her and Loy’s lovelorn look when he puts her to bed during the rainstorm. Lowlights mostly grow from the self-centered nature of the Baxter character and, I’ll be honest, just about everything about the final scene grated on me.

Overall, Broadway Bill is recommended viewing even if it doesn’t quite rank with Capra’s best.

Many thanks to Warner Archive for sending along a review copy of Broadway Bill. The title was recently released as a Made to Order DVD-R that you can order direct from the Warner Archive website. Their copy is much crisper than the screen captures presented on this page, but as my disc would not play in my desktop I had to grab these images from other sources.

Cited

- McBride, Joseph. Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success

University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

It’s an OK Capra film, though I’m marginally fonder of RIDING HGH. It has a better supporting cast, plus a couple of nice songs.

I agree on Broadway Bill, though I probably would have called it “upper middling” if that didn’t sound so awkward. I didn’t care much for Riding High–maybe because I had seen Bill several times before, so it was the more familiar version; maybe because watching them so closely together makes Capra look a bit lazy (He used a lot of 1934 footage in the 1950 movie, not just the races). Dan Brooks wasn’t my favorite Capra character in either version, but I found Baxter a little less annoying than Bing. On the other hand I thought Myrna Loy was much better than Coleen Gray and thought Raymond Walburn came across better in the original. I actually expected more songs in Riding High, but thought that what was there was weaved into the movie well.

The two movies are definitely an interesting case for comparison though, and whether we agree or not I thank you for taking the time to add your perspective.

I thought parts of BB ok, but along with the treatment of Muse, it had a downer ending (I remember gasping out loud when I first saw the film and its horse race). It’s put me off horse race pictures. Also, Baxter just seemed too old for Loy. I think Gable just would have been better, but that’s just another might-have-been to speculate over!

The funny thing is that Myrna Loy is supposed to be the youngest daughter at that table and Helen Vinson, who occupies the seat closest to their father (Walter Connolly) and is presumably the eldest daughter, is actually two years younger than Myrna!

Baxter looks a bit old to me no matter the date on the movie, but I thought the age difference here (and he was 16 years older than Myrna Loy) worked in that Bax is completely unaware of Myrna’s crush for most of the film. She’s just a pal to him. By the way, I love the shattered look that crosses her face when he jokes that he married the wrong sister. She is so good here!

I really like Warner Baxter, but yeah, I’m going to chose Gable over him most every time.

I don’t mean to downplay the treatment of Muse, but I didn’t think he put up with more here than he does in most other films. Actually, the Muse character seemed to have a freer hand than the Loy character in some regards though that was in the name of gallantry rather than any intended sexism.

I agree with Grand Old Movies – I just couldn’t buy Warner Baxter in this role, as good as he is. I also had trouble liking the film overall, but I did think the scene where Broadway Bill dies was quite moving.

I enjoyed your thoughtful review.

One of my favorite little moments in the movie is how Frankie Darro, as Bill’s crooked jockey, reacted after the tragedy. We only see him for a couple of seconds but he left no doubt of his regret. Nice touch for one of the movie’s most minor characters, who didn’t even need to be included in the scene.

I seem to be in the minority on Baxter. I usually like him and I liked him here, even if the character could be obnoxious at times.

Glad you enjoyed it, thanks for letting me know!