All the fellows love Millie Blake, small-town girl who picked up a bit of a reputation after her father died. Wild as she may be, when Jack suggests they go to New York together, Millie tells him, “That’s the one thing I won’t do.” Jack’s proposal solves Millie’s moral concerns and her lack of experience soon shows itself in their honeymoon hotel where the terrified virgin has to be reassured that Jack is quite a catch when she phones her mother. Sensing her nerves Jack asks, “Who’s your boss?” Millie meekly replies, “My husband.”

The porcelain-featured former artist’s model Helen Twelvetrees cements the brief reign of stardom she nailed down the year before in Pathe’s Her Man (1930) as she stars for RKO in their adaptation of the recent Donald Henderson Clarke novel, also titled Millie. While Twelvetrees’ fame would be fleeting, Millie allows her another opportunity to excel after the men around her let her character down. A difference between Millie and the several similar films Twelvetrees appeared in around this time is that the story doesn’t end with Twelvetrees swept into the arms of any actor.

When Jimmy Damier (John Halliday) finally gets his time with Millie he asks her what her ambition is: “To keep my independence,” she tells him. “And perhaps a little comfort.”

When marriage proves disappointing to Millie she rebels against the institution. When monogamy does the same she gets her kicks by running roughshod over the entire male sex. There is a price to pay for such independence in the final act, but Millie succeeds in the end.

No more men as boss of our Millie after she discovers her husband (James Hall) with another woman. She confronts him in a crowded cabaret and rewards the other woman with a quick jab to the chin when she talks back. Twelvetrees looks tiny, but her Millie is the daughter of a blacksmith, who seems to have taught her to defend herself. Millie leaves the pampered home her marriage had provided and takes a job at a cigar stand where she spends most of the day exchanging flirty banter with the male customers.

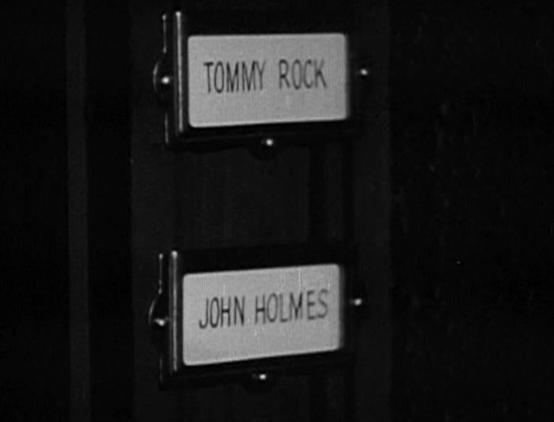

While marriage is out, Millie isn’t so hard yet as to reject love as out of hand. She overcomes the tempting advances of wealthy banker Jimmy Damier (Halliday) to take up with newspaper reporter Tommy Rock (Robert Ames). Millie settles down to a quiet life of domesticity with Tommy for a few years, but that blows up after she catches him cheating on her as well.

Millie lets her rage boil over. She slurps a few drinks, publicly dresses down and ultimately drops Tommy before departing with Jimmy. “Before I go anyplace with you, you’re coming somewhere with me,” she tells Jimmy. When he objects she says, “Say, who follows who? I follow you? No sir, you follow me.” She takes Jimmy with her to Tommy’s apartment where she erupts, smashing Tommy’s photo of her and tearing down the curtains she had added to give the place a feminine touch.

One man failed her in marriage, another failed her in an exclusive relationship, so now Millie tosses aside any qualms about traditional morality and can be found Christmas night, drunk in the arms of what appears to be a quite casual male acquaintance as she takes phone calls fending off offers from Jimmy, whose fling must have been short, and Tommy, who’s obviously broken her heart.

Millie finds support through her girlfriends, Angie (Joan Blondell), from back home, and Angie’s wisecracking friend, Helen (Lilyan Tashman), the most jaded woman of the bunch from start to finish. While the video case from Alpha Video unnecessarily tries to spice up this pre-Code title by referring to these characters as “a thinly veiled portrayal of lesbian lovers,” that’s not what I saw in the movie. The idea is spurred on by our introduction to the pair, who provide a scandalous screen capture (below) sharing a bed as their landlady hounds them for their rent.

But remember, it’s the Depression, dearie, and no one found it very strange when Blondell later shared a bed with both Ruby Keeler and Aline MacMahon in Gold Diggers of 1933.

While it would be wrong to call a bed and a roof to sleep under luxuries during the early ’30s, they could be to the poor and especially young people, just starting out and willing to sacrifice comfort for independence.

Gold diggers are what Helen and Angie are, and though they don’t have any strong desire for romance, they certainly hope to land men who can support them in style.

Above: Tashman and Blondell return from a trip upstate with some new furs and accessories. Robert Ames at left; Helen Twelvetrees between Tashman and Blondell.

Blondell, in an early supporting role released between Other Men’s Women and Illicit back at Warner Brothers, plays the ditziest of the women, but her Angie is also the one who lands a rich husband, who is then kept very much in check. With Angie’s marriage the Blondell-Tashman pairing disintegrates leaving Tashman a strong scene shared with Twelvetrees over a Christmas bottle and a whole lot of tears.

Time passes in Millie, which is divided into three sections beginning with “Youth,” which briefly covers Jack Maitland’s (Hall) courtship of Millie and their marriage night. After that a title card tells us that “Three Years Pass,” removing any jarring effect that the first scene of Millie with her infant daughter may have caused. This is the section of Millie where the men in her life let her down and make Millie into the woman that she becomes. It’s the lengthiest portion of the movie.

Later Twelvetrees is aged as another “Eight Years Pass.” Millie is still rabidly independent, but more involved in her now 16 (or 17) year old daughter’s life (Anita Louise). Jimmy, who Millie had pushed away for years, more successfully romances younger chorus girls now and is able to politely reject Millie. Up until this point Halliday has been likable in his part, even sympathetic as he was always kind to Millie despite her rejection, but he has aged into a cad who wrangles an invitation to Sunday Church service just to take a peek at Millie’s daughter, Connie Maitland. After Connie meets with his eye approval Jimmy takes to chasing the teenaged girl even more aggressively than he used to court her mother.

It all boils to a melodramatic confrontation where shots ring out over Connie’s screams and Millie winds up in a courtroom proving how much she loves her daughter.

Helen Twelvetrees gets to do a lot as Millie, beginning as an innocent bride and winding up an ashen version of the youthful Millie, who despite her wild times holds her tongue in hope of sparing her daughter’s reputation. It’s a Stanwyck-type role portrayed by more fragile and, granted, less talented, yet still capable actress.

Novelist Donald Henderson Clarke brings Millie back several years later in Millie’s Daughter, which was adapted into a movie that starred Gladys George as Millie. I have yet to see that film, from Columbia in 1947, but I see the older Millie has taken to using her married name, Maitland, and the daughter of the title is not Connie, but a Joanna, who isn’t around in this 1931 movie. Clarke wrote an even more controversial novel about a woman of modern morals called Female, which was adapted into the Warner Bros./First National movie starring Ruth Chatterton in 1933. Another strong credit for Clarke comes in his screenplay for the dark 1943 thriller at sea, The Ghost Ship starring Richard Dix.

Charles R. Rogers, an associate producer associated with RKO bought talkie rights to Millie in August 1930. Playwright Ralph Murphy collaborated with veteran Hollywood screenwriter Charles Kenyon on the screenplay which was produced by Rogers with John Francis Dillon directing. Film Daily reported on September 24 that Rogers signed Pathe star Helen Twelvetrees to star. RKO’s acquisition of Pathe was still officially a few months away, but it was reported in late July that the contracts were being prepared and that Rogers specifically was going to work on the Pathe lot if the deal went through as planned. The film went into production in November 1930 and premiered in New York, February 6, 1931.

Besides John Halliday, and even he’s a bit stiff in spots, Millie’s leading men were a bit bland making it all the easier to root for Twelvetrees’ title heroine.

Former silent star James Hall, who had co-starred with Clara Bow and Louise Brooks while a leading man at Paramount and is best remembered today for his performance alongside Ben Lyon in Howard Hughes’ Hell’s Angels (1930), was nearing the end of his film career at the time of Millie and would only appear in a few more films, his last released in 1932. After that Hall moved to Jersey City with his wife where his celebrity status was used to emcee at local clubs. He died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1940, just 39 years old. Within a couple of weeks of his passing Hollywood journalist Jimmy Fidler would report his wife was destitute.

Unfortunately James Hall was not the only member of the Millie cast to come to a tragic and youthful end, nor was he the first. As mentioned in my article about 1931’s Smart Woman, Robert Ames, who played Tommy Rock in Millie, did not last out the year, passing away that November at age 42 from a case of delirium tremens. Lilyan Tashman was just 37 when she died following cancer surgery in 1934. Director John Francis Dillon had a heart attack and died that same year. The lovely Helen Twelvetrees lasted a bit longer, but was reported to have taken her own life when she died of an overdose in 1958, just 49 years old.

Millie is one of the easiest Helen Twelvetrees’ movies to find, though given the juicy, yet relatively small, part played by the popular Joan Blondell it is surprising that it is not even better known. While Her Man is the better Twelvetrees title overall, Millie offers a more versatile showcase for the Brooklyn-born star. Blondell and Lilyan Tashman also give noteworthy performances in Millie with John Halliday shining best among the male cast members. Anita Louise doesn’t appear until the final twenty minutes and is appropriately innocent in her part as young Connie Maitland, peaking with a pair of bloodcurdling screams as Millie comes to its climax.

Also standing out are Frank McHugh, playing a reporter friend of the Ames’ character. McHugh figures late in the scenes around the courtroom and gets to sing “It’s Nice to Be a Geranium” while doing a little drunk dance amongst a party crowd in an earlier scene.

As if Robert Ames’ Tommy Rock didn’t have a porntastic enough name, get a load to the name of his roommate, played by Frank McHugh.

Former silent leading lady Charlotte Walker, Sara Haden’s mother, accords herself well as Millie’s mother-in-law. I was surprised she didn’t get much more character work in the movies after this.

Songwriter Nacio Herb Brown, whose best known hit was Singin’ in the Rain, contributes a tune titled Millie here. Performed by a trio with megaphones in a nightclub the song is a gift to Millie from the Halliday character. It’s lyrics figure as Millie’s theme song:

She isn’t a blonde

She’s not a brunette

She’s Millie the red-head and hard to forget

Look out for your heart

Look out for your nerves

She’s Millie the red-head with dangerous curvesShe’s good and she’s bad

She cannot disguise

An angel and devil look out of her eyes

If you’ve ever met

You never forget

That Millie’s a red-headed gal.

Twelvetrees even hums a few bars to Halliday later in the night after she discovers Ames’ infidelity. But apparently those singers only performed the flattering parts of “Millie” back when she was young and in full control of her own destiny. As the movie nears its end, the portion where Millie is punished for her previously carefree ways by Jimmy’s predatory behavior towards her daughter, a new bar is crooned over the accompanying title card:

She wasted her heart

On hopeless affairs

She’s Millie the red-head

But nobody cares.

After Connie is briefly shown as a toddler Millie soon leaves her husband and gives over her daughter to her in-laws to raise. The bright spot for Millie is that she refused to take any money from the Maitland family in exchange for Connie, a point that mercenary airhead Angie (Blondell) cannot figure. As quick as the point of Millie’s motherhood is raised it is dropped and we’re supposed to enjoy and root for Millie as she battles through the relationships that follow.

In the end the mother must save the daughter from the clutches of one of the many men Millie encountered during her days of independence. This takes a major toll on her but as Millie winds down our heroine appropriately does not win any man of her dreams, but instead claims a seemingly more concrete role in the life of her daughter.

Millie was released on DVD by Alpha Video in 2006 (accompanying screen captures from my copy) and is also available to stream

on Amazon Instant Video. By all means pick-up the dirt cheap DVD, but if you’re just going to check it out online do so for free on YouTube (HERE as of this writing). Turner Classic Movies also plays it on occasion. TCM needs to correct the brief synopsis they have on their site: Millie was never a prostitute.

Grrr! I really wish I had read this post sooner and recorded “Millie”. Ah well! Will keep an eye on the TCM schedule…

Good review of this underrated pre-code gem. Helen Twelvetrees is a cutie. The DVD transfer is pretty nice, unlike some other titles from Alpha.

Thanks, Anthony, it’s a favorite of mine, so I’m glad you enjoyed my look at it. Helen Twelvetrees is very addictive, I wound up writing an entire book about her and her movies! Totally agree about the DVD, nicest looking Alpha disc I’ve run across so far—well worth the 5 or 6 bucks.