First National’s Show Girl in Hollywood, released in April 1930, ties together many individually interesting elements that should add up to an all-time classic. While that somehow doesn’t happen, I do hope to sell you on seeking this title out

First National’s Show Girl in Hollywood, released in April 1930, ties together many individually interesting elements that should add up to an all-time classic. While that somehow doesn’t happen, I do hope to sell you on seeking this title out from the Warner Archive to see how great a whole these many pieces add up to for you.

The story centers around a character named Dixie Dugan, a name which may ring a bell. Dixie made here greatest fame as a comic strip which ran in newspapers into 1966.

Dixie Dugan

The character, drawn by John H. Striebel, strongly resembled film star Louise Brooks. This was no coincidence as Brooks’ biographer Barry Paris wrote that Dixie’s creator, writer J.P. McEvoy, “modeled Dixie on Louise” (204) right from the start.

But the comics were actually Dixie’s final landing spot.

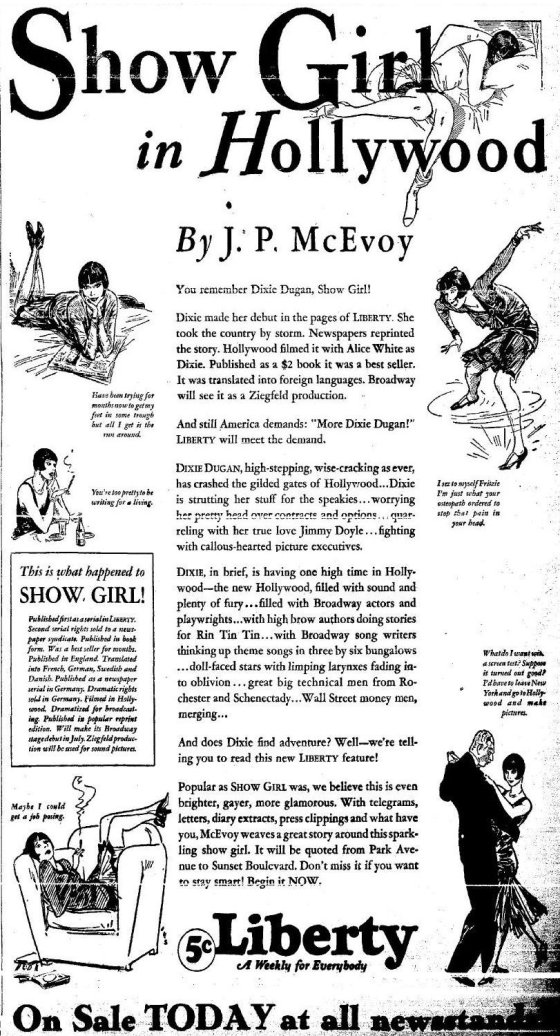

Dixie Dugan wasn’t around very long before making her way to the comics, but she had been around nonetheless. The character was created in McEvoy’s original story, Show Girl, which began its serialized run in Liberty magazine early in 1928.

Dixie Dugan wasn’t around very long before making her way to the comics, but she had been around nonetheless. The character was created in McEvoy’s original story, Show Girl, which began its serialized run in Liberty magazine early in 1928.

McEvoy wrote two Dixie Dugan novels, Show Girl and Hollywood Girl, the latter of which our movie is based upon. The original Show Girl graduated from magazine serial to novel in book form later in 1928. That same September the first film, also titled Show Girl, premiered.

This first Show Girl film was also from First National, but was a silent film with music and additional sound effects added via the Vitaphone process. It charted the rise of Dixie Dugan from nightclub entertainer to Broadway star handing a big publicity assist to reporter Jimmy Doyle. Dixie and Jimmy marry at the end of Show Girl.

Dixie makes the move from Broadway to Hollywood in Show Girl in Hollywood, though she and Jimmy (now Jimmie) aren’t married in this one.

An advertisement for the latest issue of Liberty Magazine featuring the Show Girl in Hollywood story by J.P. McEvoy and including illustrations of Dixie Dugan by John H. Striebel. Originally published in the Oakland Tribune, June 7, 1929, page 9

Jimmie is no longer a reporter either. He is author of Rainbow Girl, a Broadway flop he blames on his financial backer because he wasn’t allowed to star Dixie. The writer and his understudy begin their journey in New York but Jimmie and Dixie will each soon find their way to Hollywood.

In between the two films McEvoy’s Dixie Dugan kept busy. The second film was based on his second novel, titled Hollywood Girl, which was adapted for First National by Harvey Thew.

The first story remained alive when Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. Brought Show Girl to Broadway in July 1929. Ruby Keeler starred as Dixie and Frank McHugh as Jimmy in a show also featuring Jimmy Durante’s Broadway debut. Somehow it flopped.

First two panels of an early SHOW GIRL strip before the title was changed to DIXIE DUGAN. Originally published in the Independent of Helena, Montana, November 4, 1929, page 2.

That October Show Girl first appeared in the papers as a comic strip by McEvoy and Streibel. The title of the comic was changed to Dixie Dugan just before the calendar turned to 1930.

In the comics Dixie eventually morphed into a working girl, and would later be depicted as such on the screen in Twentieth Century Fox’s war-time Dixie Dugan (1943). She remained a comic strip regular through 1966.While Dixie Dugan claimed a small but daily part of the lives of the World War II generation and their Baby Boom offspring into the Vietnam era, this pop culture glow is just one of Showgirl in Hollywood’s footnotes of interest.

Vitaphone

Warner Brothers and First National were soon famed for their backstage musicals, but Show Girl in Hollywood offers a fascinating peek at the behind the scenes goings-on of a Hollywood musical.

Of even greater curiosity is the peek it gives us at the Vitaphone process that was used not only for Show Girl in Hollywood, but the film within the film, Rainbow Girl.

I’m not a nuts and bolts guy but from my understanding, greatly enhanced by Show Girl in Hollywood’s visuals, the Vitaphone process gave the best sound by way of the most labor and equipment. Rather than having a soundtrack included directly on the film itself, the Vitaphone process recorded the soundtrack separately to a phonograph record which was synchronized to the film itself.

As for playback at the movie theater, Kyle Westphal of the Northwest Chicago Film Society explains: “Running a feature meant at least three people in the booth—two to run the projectors and another to synchronize the 16-inch disk to the picture. Anything but constant and even playback of sound and image broke synchronization between the two.”

He offers up Singin’ in the Rain (1952) as depicting the most famed example of what could go wrong in his introduction to this interview with The Vitaphone Project’s Ron Hutchinson about the process specifically in relation to Show Girl in Hollywood.

Show Girl in Hollywood offers several glimpses of the equipment and the filming process as Dixie wanders around the Superb Productions lot which is, of course, First National’s own digs.

In the film we see Dixie ruin a shot when she walks onto a soundproofed set during filming.

Later, Jimmie uncovers a bit of sabotage when former studio director Frank Buelow brags to his old assistant director about the destructive advice he has given Dixie. Jimmie is seated in a sound booth and hears every word Buelow says from under a distant microphone.

And most impressively, Show Girl in Hollywood offers dual entertainment by way of a a complete Rainbow Girl musical number shown to us from the vantage point of the Vitaphone production crew as they record Dixie’s performance in the studio.

Technicolor

Unfortunately Show Girl in Hollywood’s Technicolor sequences no longer survive for us to view. But a little imagination along with knowledge of where the color sequences had appeared earn the film some bonus points on creative grounds.

Most sources offer a general report that the Technicolor sequences were used for the last reel of Show Girl in Hollywood: Basically Dixie’s final number in Rainbow Girl, “Hang Onto a Rainbow,” which was a lavish extravaganza featuring many performers wearing bizarre costumes and aligning into patterns that will put an inkling of Busby Berkeley* in your mind.

*Note: Jack Haskell directed the dance scenes here, Show Girl in Hollywood being the first of four films he’d work on for Warner Brothers and First National that year.

The October 12, 1929 edition of Motion Picture News doesn’t make mention of Dixie’s big final number appearing in Technicolor, but does report that Warner Brothers had taken two Technicolor cameras out to film Hollywood’s elite as they entered the premiere of Mammy (1930) starring Al Jolson. The piece specifically notes that “Technicolor shots were made for future use as inserts in Show Girl of Hollywood.”

Jolson himself is shown arriving with wife Ruby Keeler, three years before 42nd Street, at the premiere of Rainbow Girl starring Dixie Dugan. By virtue of the Motion Picture News tidbit we know that footage is actually of the Jolsons showing up to Al’s own Mammy.

I’m picturing Show Girl in Hollywood transitioning from black and white to Technicolor right at the beginning of this premiere sequence, and I’m imagining it would have been a spectacular way to greet Rainbow Girl as finished product and see Hollywood burst to life on an opening night through the use of color.

The Jolsons weren’t the only stars to show up for Rainbow Girl’s premiere. Show Girl in Hollywood boasted a few other guest stars.

Guest Appearances

Al and Ruby just wave to us from their car, but Show Girl in Hollywood’s next guest actually makes her way down the red carpet to greet us.

“Good evening folks,” seventeen year old Miss Loretta Young says. Then sounding every bit her age: “This certainly is a big crowd and heaps of lights and lots of fun and excitement for the premiere of the Rainbow Girl. Thanks.”

Noah Beery stands with our red carpet host next: “I’m always glad to see the younger generation succeed. And I take advantage of this opportunity to congratulate Miss Dugan.”

From the background another youngster steps up to the mic. It’s Noah Beery, Jr. Who offers, “Well, my dad knows what he’s talking about, so that goes for me too.”

Following our special guest stars each of the key film characters arrive and say a few words. All but our villain, Buelow, that is; the red carpet host doesn’t recognize him and eventually shoves him away from the microphone to make way for Dixie and Jimmie.

After that we head inside the theater where the projectionists compliment the film while setting up the final reel. That big final production number comes next before a triumphant Dixie takes to the stage after being introduced by a youthful Walter Pidgeon.

Show Girl and Hollywood winds to its happy ending as Dixie and Jimmie come together and Rainbow Girl’s producer, Sam Otis, stands for one final cost cutting chuckle. The End.

It sounds like it should be much more than a curiosity, doesn’t it?

Beyond all those bits of trivia on film Show Girl in Hollywood also offers one last meaty role for a former silent star and a pretty humorous talkie role for one of the original Keystone Kops.

But Show Girl in Hollywood finds itself savaged largely on account of its star.

Alice White as Dixie Dugan

Poor Alice White. Yes, I’m in that camp.

Descriptions of Alice on screen typically congratulate her for being cute and energetic but tear into her for not having any talent. She’s a petite figure with high cheekbones, puckered lips and giant eyes whose pupils glide every which way. Formerly a brunette, sometimes a redhead, she wears a bleached blond bob by this point, her best remembered hairstyle, and unleashes a screen personality that draws comparisons ranging from Betty Boop to Clara Bow.

Descriptions of Alice on screen typically congratulate her for being cute and energetic but tear into her for not having any talent. She’s a petite figure with high cheekbones, puckered lips and giant eyes whose pupils glide every which way. Formerly a brunette, sometimes a redhead, she wears a bleached blond bob by this point, her best remembered hairstyle, and unleashes a screen personality that draws comparisons ranging from Betty Boop to Clara Bow.

White pushed her way from studio stenographer onto the screen insisting on nothing less than second supporting actress along the way. She debuted in The Sea Tiger with Milton Sills and broke out as Lorelei Lee’s pal Dorothy Shaw in the original screen production of Anita Loos’s Gentleman Prefer Blondes (1928).

She first worked with boy wonder director Mervyn Leroy in 1928’s Harold Teen and Show Girl in Hollywood would be their sixth and final film together. Leroy’s own legendary run hit its first major high note less than a year later with the January 1931 release of gangster classic Little Caesar. He was done with Alice White films by then.

Leroy and White are often romantically linked by Hollywood historians with Richard Barrios mentioning Leroy’s “offscreen interest” in his star (207) and Eve Golden writing that LeRoy next turned his interests to Ginger Rogers while Hollywood “whispered that Alice White had slept her way to success” (340).

Leroy and White are often romantically linked by Hollywood historians with Richard Barrios mentioning Leroy’s “offscreen interest” in his star (207) and Eve Golden writing that LeRoy next turned his interests to Ginger Rogers while Hollywood “whispered that Alice White had slept her way to success” (340).

“Alice White Reigning Queen of First National Studios” was the headline on a 1930 Mayme Ober Peak article which offers clues as to how Alice may have sustained her success beyond the casting couch.

Warner Brothers purchased their controlling interest in First National late in 1928, at about the time of the release of the first Show Girl, and originally the two studios ran as separate entities.

Ober Peak noted the recent departures of First National stars Corinne Griffith, Colleen Moore and, most recently, Billie Dove. “If it weren’t for the glamorous presence of Marilyn Miller, First National Studios would look like an abandoned beehive,” she wrote. And, Alice, one of First National’s top remaining draws, likely remained because of the bottom line: She was making $150 per week.

And she griped about it. In fact, much of Show Girl in Hollywood, especially those scenes after Dixie “goes Hollywood,” bear a sharp resemblance to the Alice White legend. Later on in the decade Alice White reflected upon the hard time she gave her bosses and her fall from grace, explaining, “I was a star and I was paid like a bit player, and simply couldn’t keep up the front that was necessary.”

And she griped about it. In fact, much of Show Girl in Hollywood, especially those scenes after Dixie “goes Hollywood,” bear a sharp resemblance to the Alice White legend. Later on in the decade Alice White reflected upon the hard time she gave her bosses and her fall from grace, explaining, “I was a star and I was paid like a bit player, and simply couldn’t keep up the front that was necessary.”

After Dixie turns temperamental Jimmie tells her, “Don’t kid yourself, honey. Motion picture producers are businessmen. Making motion pictures is their business. Not arguing with temperamental dames.” The line didn’t hit home for Dixie and it seems it didn’t do much for Alice either.

Alice White’s performance as Dixie Dugan in Show Girl in Hollywood consists mostly of rolling her eyes from one side of her head to another and botching the delivery of the better portion of her lines. That said, she does offer a certain carnal charm.

She speaks slowly coating each word with a youthful naughtiness. Her tone varies little and almost always suggests the bedroom, if not with her words certainly with those eyes. No, Alice’s Dixie isn’t actually using sex to get what she wants, just flaunting it as reminder that it’s there.

But Alice White can’t turn this off. It infects every line, even her scenes with other women, mostly limited here to those with former silent star Blanche Sweet, who easily rides away with every scene they appear in together.

Alice wisecracks with sex appeal to much better effect with the male stars of Show Girl in Hollywood. Her put-downs are assured by her position with boyfriend Jimmie Doyle, played by Jack Mulhall; She’s businesslike with dabs of childlike innocence and impudence in response to her older producer, Ford Sterling as Sam Otis; But Alice is at her best with John Miljan, who plays sleazy Hollywood director Frank Buelow.

Miljan’s Buelow is dangling what Dixie wants: A part in his film. She chases the opportunity from New York to Hollywood only to be spurned by Buelow’s producer, Sam Otis.

Bumping into Buelow on her way out of the studio, Dixie is soon in his office listening to Buelow’s reassurances.

“You’re a peach, Mr. Buelow,” she tells him.

“You mustn’t call me Mr. Buelow,” he says taking her hand in his. “Call me Daddy. It’s better.”

“You don’t need to hold it,” Dixie says of her hand. “I won’t hit you.”

Buelow tries his best to get Dixie to give him what he wants suggesting she come up to his house for a private party where he’ll have her contract ready for her to sign.

Dixie fights back saying, “I’m kind of suspicious of contracts that aren’t signed in the daytime. In a business office.”

Buelow certainly would have persisted in his chase of Dixie had he not pushed Otis to his own breaking point. Soon enough Buelow’s name is being scraped off of his office door as he reads an interoffice memo from Otis dismissing him: “… as far as this company is concerned, you are just a memory.”

Later, after she has secured the leading role in Rainbow Girl, Dixie runs into Buelow while lunching at the Montmartre. “Hello big shot, run any girls out from New York lately?” she asks him.

The sex still oozes from Dixie, but cast out of the studio Buelow is little more than an impotent plaything for self-assured film actress.

Buelow asks her how she is and Dixie replies, “If I felt any better I’d be a national menace.” He tells her that he’s happy for her success and asks if he could join her at her table. “Sure, sit down. I’m not proud,” Dixie replies.

Once seated Buelow begins to win Dixie over again, but with no hope of sex he turns to revenge and convinces the Hollywood novice that she and her production are both being mishandled by a director who used to be his chauffeur.

“I guess I’d be all washed up if my first picture was a flop,” says Dixie, taking Buelow’s condemnation of Rainbow Girl completely to heart.

Buelow offers some flattery and reassurances when he tells Dixie he’s just signed with another studio, Ideal, and that she could always have a spot with him. “You sure chop that baloney fine,” Dixie says, at least understanding that Buelow is a louse on a personal level, even if she trusts him too much with professional matters.

Buelow drives Dixie back to the studio, where she has kept the entire cast and crew of Rainbow Girl waiting on her. But Dixie doesn’t report to the set. Instead she storms Sam Otis’ office to get all of Buelow’s complaints off her chest.

“So I’ll tell you how this picture is going to be made,” Dixie tells Otis mentioning both rewrites and a new director. “I’m not asking, I’m demanding,” she says, giving the producer just a half hour to get back to her.

While dishing out more temperament to Jimmie a shadow appears on the other side of Dixie’s dressing room door and the familiar screech of the razor blade begins to remove her name from the glass. Dixie receives her own memo from Otis, his message concluding just as it had previously for Buelow: “You are just a memory.”

The Men of Show Girl in Hollywood

The actors wearing the primary white and black hats in Show Girl in Hollywood, Jack Mulhall and John Miljan, were each silent film veterans, especially Mulhall, whose screen career dated back to 1910. Both men proved more than equal to their talkie tasks in this film.

Each of these men continued working well into the 1950s, but both had already enjoyed their best days by the time of Show Girl in Hollywood.

I was especially impressed by Jack Mulhall, actually the elder of these two men by five years and already past 40 when playing the very boyish Jimmie Doyle. While Miljan has an easier task in playing the scoundrel Buelow, Mulhall could have easily proved unconvincing as an up-and-coming writer hooked on his mid-20s understudy.

I was especially impressed by Jack Mulhall, actually the elder of these two men by five years and already past 40 when playing the very boyish Jimmie Doyle. While Miljan has an easier task in playing the scoundrel Buelow, Mulhall could have easily proved unconvincing as an up-and-coming writer hooked on his mid-20s understudy.

He immediately endears our sympathy when Rainbow Girl flops on Broadway and Buelow quickly turns Dixie’s head with ideas of Hollywood. Dixie leaves Jimmie behind and Mulhall disappears from Show Girl in Hollywood for awhile, but when times are tough out West Dixie sends Jimmie a series of telegraphs that add up to an apology.

Meanwhile, out in Hollywood, producer Sam Otis discovers that not only was recently dismissed Buelow a lousy person, but that his creative trips to New York consisted of stealing his ideas from Broadway shows. It’s been revealed to him that the former Buelow project he’s put new director Kramer in charge of is actually Jimmie Doyle’s Rainbow Girl.

They don’t even share the screen together, but Otis and Jimmie’s negotiations over the Rainbow Girl property, facilitated by Otis’s secretary (Virginia Sale–Chic’s sister) show each character at his best.

Jimmie, loaded down with telegrams from Dixie, takes the call from Hollywood and turns down any offer on Rainbow Girl because he plans to produce it again himself, presumably with Dixie in the lead. When he learns that the studio only wants film rights he assents and makes his demands: He wants $20 thousand cash for the rights, a 6-month Hollywood contract at a thousand per week and his fare paid to Hollywood.

“That’s fine,” Otis relays to his secretary. “Tell him we’ll give him a thousand dollars cash, a 3 months contract at $100 a week, and we’ll advance his fare to Hollywood.”

The secretary returns in a moment: “He says all right.”

“He did?” says Otis. “He must be crazy.” The other men in conference with the boss all chuckle.

Ford Sterling plays Rainbow Girl’s producer, Sam Otis. Slapstick fans know Sterling as the Chief of the original Keystone Kops, but by 1930 the 47-year-old Sterling appears in his own face—no fake goatee—and seems made for character parts in talking films.

Ford Sterling plays Rainbow Girl’s producer, Sam Otis. Slapstick fans know Sterling as the Chief of the original Keystone Kops, but by 1930 the 47-year-old Sterling appears in his own face—no fake goatee—and seems made for character parts in talking films.

Upon arriving in Hollywood Jimmie and Otis almost immediately butt heads over who should play the lead in Rainbow Girl. Jimmie is holding out for Dixie and, little surprise, Otis is doing the same, though neither realizes that they’re promoting the same girl to the other.

Since Show Girl in Hollywood is, after all, a Hollywood film, Sterling’s producer remains light and kind-hearted. He’s a businessman first, yes, but he wrings his hands a bit more than is believable over Dixie’s hard luck and really takes a personal interest in her fortunes for no other reason than the kid has had a tough break.

Mulhall’s Jimmie remains even-keeled and honest throughout Show Girl in Hollywood, his virtues even rubbing off on the Dixie character somewhat. It is really thanks to her relationship with Mulhall’s Jimmie that we can see through Dixie’s shallow exterior and accept her as being more than she may appear to someone such as Buelow.

Jack Mulhall’s career soon fell off a cliff. He was making $2,250 per week in 1930 and saw himself bumped up to $2,750 after a jump to RKO. “I knew it was all over when they started saying, ‘This part calls for a young Jack Mulhall,’” he recalled in 1955.

Mulhall found himself on the wrong side of the news in 1933 when a wild night with a friend led to assault and battery charges. Mulhall and a pal stumbled into the wrong home, drunk, and what’s described as a pretty wild brawl broke out.

Mulhall was sued for damages of $135,000 and while I couldn’t discover exactly how that case turned out it was only a year and a half later that Mulhall filed bankruptcy charges claiming $355,000 in debts versus just over $6,000 in assets. One item alone amounted to $240,000, but Mulhall didn’t specify what that was.

25 years of mostly bit parts followed.

Blanche Sweet as Donny Harris

“I’m 32. And in this business when you’re over 32 you’re older than those hills up there.”

Former silent star Blanche Sweet stands as one of the highlights of Show Girl in Hollywood. Sweet had been on the stage since she was an infant, but is most famously recalled as D.W. Griffith’s leading lady at the Biograph from about 1910-1914, in between similar such runs for Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish.

After Judith of Bethulia (1914) she jumped from Griffith to De Mille and worked at Famous Players-Lasky through 1917 before dropping off of the screen for a couple of years. One of her Famous Players-Lasky directors was Marshall Neilan, whom Sweet married in 1922.

She scored one of her most memorable successes starring in 1923’s Anna Christie for Thomas Ince before she and Neilan signed with MGM for films such as Tess of the D’Urbevilles (1924) and The Sporting Venus (1925).

Sweet’s career faded before the end of the silent era and her marriage to Neilan ended in 1929. She went overseas to star in The Woman in White (1929) and then came home to talk on screen for the first time in the Vitaphone one-reel short Always Faithful (1929).

Sweet’s career faded before the end of the silent era and her marriage to Neilan ended in 1929. She went overseas to star in The Woman in White (1929) and then came home to talk on screen for the first time in the Vitaphone one-reel short Always Faithful (1929).

Her final three films would each be talkies for a different studio. All were released in 1930: The Woman Racket for MGM; our Show Girl in Hollywood for First National; and The Silver Horde for RKO.

By 1933 Blanche Sweet seemed to have bottomed out worse than even Jack Mulhall. At least Mulhall had screen work and assets of a few thousand. Sweet declared bankruptcy listing her only assets as $200 in furniture plus two life insurance policies.

She was back on track both professionally and personally by 1935 when she began the year on Broadway in Robert Sherwood’s The Petrified Forest. She played the Mrs. Chisolm—the part taken up in the screen version by Genevieve Tobin—in the stage production starring Leslie Howard with Humphrey Bogart.

Later that year she married former co-star Raymond Hackett, a union which lasted until his death in 1958.

Blanche Sweet appeared in a few additional Broadway productions after The Petrified Forest and later made a few appearances on television following Hackett’s passing.

Blanche Sweet appeared in a few additional Broadway productions after The Petrified Forest and later made a few appearances on television following Hackett’s passing.

Given the evidence of Show Girl in Hollywood it is a shame that there were no more feature films with speaking roles for Blanche Sweet.

Sweet’s background leads me to wonder if period audiences shared my goosebumps when her Donny Harris first meets with Dixie Dugan. Dixie is just coming from the obnoxious Buelow’s office when she bumps into Donny on the lot and asks if she works there too:

“I did once. When this part of the studio was just an orange grove.”

Blanche Sweet is handed two big scenes as Hollywood has-been Donny Harris and she makes the best of both of them.

First, when she has Dixie back to her house after they’ve first met our famed silent star soon breaks into song. Sweet told author Anthony Slide that whenever Richard Griffith, former curator at the Museum of Modern Art, would see her he’d always sing a few lines of that song, “There’s a Tear for Every Smile in Hollywood” (365).

Later Donny pops up as a Rainbow Girl cast member after Dixie had insisted upon her appearing in the film. But Donny’s comeback becomes the unintended casualty of Dixie’s showdown with producer Otis after she returns puffed up from that lunch with Buelow.

While Dixie takes the offensive to defend herself against Jimmie’s rebukes, director Mervyn Leroy allows the legendary silent film star her final big moment on film:

It’s all over for Sweet’s Donny. She rises from this window and is a small figure in a dark empty house, one which she’s already admitted to Dixie is kept open only to retain the last vestiges of her image. At her desk Donny reaches for a vial, but the silence is unfortunately interrupted to exchange some lines with her chauffeur.

Elsewhere Jimmie argues with Dixie until the phone rings. It’s Donny. Dixie senses something is wrong and Donny confirms her worst fears: “Dixie. I’m going away. And I’m not coming back.” She drops the phone in pain.

This is Dixie Dugan’s moment of reckoning. She and Jimmie race to Donny’s and the scene that follows turns out funny for all of the wrong reasons as a mostly silent Blanche Sweet steals every moment from Alice White who is really giving it her dramatic best.

Show Girl in Hollywood doesn’t quite have the nerve to send Donny Harris the way of Max Carey or Norman Maine, but Blanche Sweet still manages to deliver this film’s most dramatic moments in a character that has up until this time seemed all too close to reality.

Final Thoughts

Show Girl in Hollywood remains a fascinating film even if it is buoyed more by the trivia not only surrounding it, but unfolding within it, than it is by virtue of its actual content.

If you happen to like Alice White than Show Girl in Hollywood can’t miss. If you’re not a fan than this isn’t the film that’s going to turn you into one. All of her weaknesses are on display.

There’s even some confusion as to whether Alice does her own singing or not. A somewhat mysterious vocalist named Belle Mann is credited with Alice’s songs in the original Show Girl and it’s quite possible she was back for the same duties in Show Girl in Hollywood as well.

But I can’t help but to think if you like the much better known Busby Berkeley musicals that Warner Brothers released just a few years later, titles such as 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, and Footlight Parade (all 1933), than you’ll find Show Girl in Hollywood a worthwhile viewing experience.

It doesn’t hold a candle to the others in terms of music or performance, but stands out in offering a behind the scenes look at the Hollywood musical rather than the stage performances of the others. In doing so Show Girl in Hollywood offers an entirely different type of spectacle.

And if anyone can ever turn up that Technicolor footage I could see Show Girl in Hollywood’s reputation improving by leaps and bounds.

In addition to all of the Dixie Dugan history outlined at the top of this article, First National also produced a separate French language edition of SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD titled “Le masque d’Hollywood” and starring Suzy Vernon as Dixie.

Alice White would play Dixie in an NBC radio version of SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD aired during the “Del Monte Coffee Hour” in May 1930. An original newspaper advertisement for that program is shown on this page.

SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD is a Warner Archive DVD-R manufactured on demand and can be purchased either HERE

through my Amazon affiliate account (thank you!) or at the Warner Archive website itself.

The First National release makes occasional appearances on Turner Classic Movies as well which is where my copy, and the resulting screen shots, came from.

Sources

- “Alice White’s Back Again! Recall Her?” Milwaukee Journal 4 Sep 1938: 7. Google News. Web. 23 Nov 2012.

- Barrios, Richard. A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film

New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. 207.

- ”Blanche Sweet Is Bankrupt, Report.” Hayward Daily Review 21 Apr 1933: 5. NewspaperArchive. Web. 22 Nov 2012.

- Golden, Eve. Bride of Golden Images

Albany, GA: BearManor, 2009.

- Greene, Walter R. “Talk in Hollywood.” Motion Picture News 12 Oct 1929: 32C. Media History Digital Library. Web. 22 Nov 2012.

- Hall, Leonard. “Reeling Around.” Photoplay April 1929: 39. Media History Digital Library. Web. 22 Nov 2012.

- ”Jack Mulhall Broke Along With Extras.” Ogden Standard Examiner 24 Mar 1935: 3. NewspaperArchive. Web. 21 Nov 2012.

- ”Jack Mulhall, Film Actor, Is Defendant.” Nevada State Journal 18 Aug 1933: 1. NewspaperArchive. Web. 21 Nov 2012.

- Ober Peak, Mayme. “Alice White Reigning Queen of First National Studios.” Boston Globe 6 May 1930: 4. Boston Globe Archive. Web. 24 Nov 2012.

- Paris, Barry. Louise Brooks: A Biography

. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989.

- Slide, Anthony. Silent Players

. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002.

- Thomas, Bob. “Jack Mulhall Now Is Actors Union Agent.” Mt Vernon Register News 9 Nov 1955: 9. Newspaper Archive. Web. 21 Nov 2012.

- Thomas, Bob. “TV Films Are Boom to Former Hollywood Stars.” Lowell Sun 17 Jan 1952: 16. Newspaper Archive. Web. 21 Nov 2012.

- Westphal, Kyle. “On the Vitaphone: Show Girl in Hollywood.” North West Chicago Film Society 8 Aug 2011. Web. 22 Nov 2012.

[phpbaysidebar title=”eBay Shopping” keywords=”Alice White,Blanche Sweet” num=”5″ siteid=”1″ category=”45100″ sort=”EndTimeSoonest” minprice=”39″ maxprice=”699″ id=”2″]

Well I think Alice White was a great actress,and to single her out like that,what about all the other so called actresses,that done the same thing..Let’s not be judgmental here…If yuo want to single out her then do the same for the rest,……

I’m not quite sure what I singled her out for. I like Alice White and was originally drawn to the movie because of her–all of the other elements were a pleasant surprise.

But all in all, I think I gave Alice White a pretty fair shake and a good deal of the benefit of the doubt in terms of what happened to her career after 1931 or so.

I’m sorry if you don’t think I did her proud, feel free to let me know any specific problems you may have with the piece. And thanks for reading it!

Very interesting article Cliff! I saw Show Girl in Hollywood quite a while ago at Jonas from All Talking! All Singing! All Dancing! suggestion. It’s a cute picture and I do like how it’s very meta like Singin’ in the Rain.

I’m curious now about Alice White and her career. Especially all that drive she had that didn’t seem to get her very far in terms of a long career. It seems she got famous quick but it fizzled quickly too.

To Jobill’s point, I wonder how many other actresses careers were similar.

And I also wonder about other very driven individuals like Joan Crawford who had long careers. In the case of Crawford, longer than it should have been.

Thanks for making it down this far, Raquelle. It’s such a tricky era and Alice White advanced before the boatloads of Broadway talent came in, so I’m sure that wave helped end her initial run. She was with First National through 1931–even billed over Edward G. Robinson in “The Widow from Chicago” that year–but her contract was not renewed once it was up. She doesn’t come off well in a lot of the reporting from the period and by the late ’30s even she was admitting that she had been too demanding. I love her in support in “Employees’ Entrance” (1933) and was just charmed all over again this weekend watching her in “Secret of the Chateau” (1934). She made the papers a couple of times for “sex scandals” but seems to have left on her own terms when she married again in 1941 (“I went domestic with a vengeance.”) I’ve been curious about her for awhile and went digging in the papers a couple of years ago to see if I could find out any more–posted about that here.

I really enjoyed your review Cliff and I think you did Alice proud.

I love Alice White but I’m not going to stand up and say her acting

performances are award winning material. She looked adorable

and I thought was perfect for the roles she played – mostly

feather brained chorus girls, sweethearts etc whose head is

usually turned by some seedy promoter or villain but whose

boyfriend is usually there at the end to kiss away her tears.

Judging from some of the contemporary reviews most critics

liked her at first.

I think if you want to see really, really bad acting there is an

actress in “Broadway Babies” who plays the vamp – I think her

name is Jocelyn Lee. She is so bad she is actually hilarious and I

watch the movie for her just as much as Alice. From putting the

wrong emphasis on different words that can change the whole

meaning of the sentence to speaking in a cooing Marilyn Monroe

type voice she is a real knock out and a must see!!