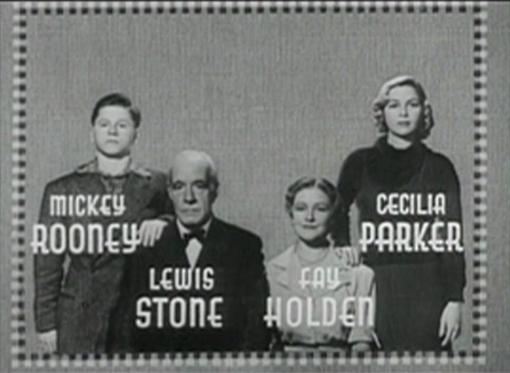

What a strange experience A Family Affair (1937) is for us in retrospect. The first in a series of 16 Hardy family movies, 13 of which were released between 1937-1942, watching A Family Affair through a rear-view mirror leaves me to wonder why there were any sequels at all. Oh, it’s not that I don’t like the Hardy movies, I pretty much enjoy them every time, and it’s not that A Family Affair is necessarily a bad movie, it’s just that it’s a very different Judge Hardy (literally!) and Hardy family acting in ways we’re not all that familiar with. All that is except for young Andrew Hardy (Mickey Rooney), who finds nowhere near enough face time in A Family Affair, but uses what time he does have to introduce us to a character who’d become an American institution and pretty much single-handedly provide us with the answer to the question, “Why more Hardy movies?”

A Family Affair’s origins are interesting in and of itself. First off Hardy stalwarts Lewis Stone and Fay Holden are nowhere to be found. More on other differences in a moment, but for now we’ll trace our Hardy timeline back to Eugene O’Neill of all people! Now the esteemed O’Neill did not have any direct hand whatsoever in creating Hardy Family folklore, those roots trace to much less notable playwright Aurania Rouveral, whose Skidding was the basis for A Family Affair, but the coming of age play Ah, Wilderness! did spring from O’Neill’s pen. MGM adapted Ah, Wilderness! to the screen in 1935 with a cast including Lionel Barrymore, Spring Byington, Cecilia Parker, Mickey Rooney, Eric Linden, and Charley Grapewin, all members A Family Affair’s cast soon thereafter, and all but the last two Hardy Family members.

Yes, Lionel Barrymore, not Lewis Stone, plays Judge James K. Hardy in the initial offering, and boy is it ever so hard to adjust to that! Barrymore’s Judge Hardy is not that far off of Stone’s impressive mark, but at the same time he’s not even close. This Judge is the star of A Family Affair and he’s pretty much all business. Not exactly humorless, perhaps even a touch more folksy, but all the same a little grating as Barrymore tends to both over and underplay the Judge at various points throughout.

When Nichols, a sleazy newspaper man who’s objected to the aqueduct to be constructed in Carvel, has a change of heart that’s obviously been spurred on by a greasing of his palm he tells the Judge he’s ready to drop his complaint. Hardy, who sees merit in the original suit, listens knowingly, wears a creepy smile in original response to Nichols’ offer of a bribe, then physically tosses the younger man out of his offices! Can you imagine Lewis Stone grabbing someone by the neck and putting a boot to his backside?

Barrymore also plays host to one of the Judge’s famed heart-to-hearts, only not with Andy, but with his married daughter Joan Hardy Martin (Julie Haydon), who’s subsequently dropped from the Hardy family quicker than you can say Chuck Cunningham. Joan, the darkest Hardy you could ever imagine, has been on edge because she and her husband Bill (Allen Martin) have recently separated, the fault pretty much all hers from evidence presented to us. See Bill’s been very busy at work lately and hasn’t been paying enough attention to Joan. Another man began showing her attention and Joan was receptive enough to go out with him one night and get a private room at the Blue Rabbit Inn, a dive the Judge says he regrets not shutting down when he had the chance. Anyway, Bill happened into the Blue Rabbit himself on that night and he pulled the curtain just as this mystery fellow was planting a kiss on Judge Hardy’s little Joanie. Bill blew up and word spread around and now the Judge’s aqueduct foes plan on using this little family scandal against the him on the political front.

So Joan gets it all off her chest sitting across from the old man who remains pretty much stone-faced throughout the conversation. Joan’s been busting out in tears all evening, even sharing a cry with Marion (yes, Cecilia Parker) in a most un-Hardylike scene earlier in the film. In her talk with the Judge she finally says what’s been bugging her, “You see,” she says, “I thought I might kill myself.” Well, the Judge didn’t break into a chuckle or anything, but when asked by his daughter if he ever harbored any similar feelings himself his down home answer is that he’s typically too busy to get that upset over anything, what with a new activity always set to distract him just around the corner. Lewis Stone, we missed you here.

Spring Byington is about as invisible as Fay Holden typically is, so nothing really seemed off-kilter there, and Sara Haden is already on the scene as Aunt Millie, so that added some familiarity, but Cecilia Parker’s Marion was a bit more involved than I’m used too a little bit snarky as well. Marion is returning home from college and she met a young man, Wayne (Eric Linden) on the train back. While her mother finds her tale of a train pick-up scandalous I assure you it was completely innocent. Wayne’s not a Carvel native, he’s coming to town for a job involving that aqueduct that the Judge opposes, which naturally leads to some conflict later. Our Marion of A Family Affair is about as involved in the story as sister Joan is, that is to say their tales are pretty much stories 2a and 2b behind only the main affair involving the Judge.

Left to Right: Mickey Rooney, Spring Byington, Sara Haden, Cecilia Parker (standing), Julie Haydon (sitting)

Then there’s son, Andrew, who only appears sporadically throughout A Family Affair for dashes of energy and humor. Mickey Rooney pulls out all the stops this first time around and while we don’t see much of him his main storyline is an important evolution in the life of the Andy Hardy America soon comes to know and love. When his mother insists he go to the Sutton Party, young Andy’s reaction is disgust as he exclaims, “Holy Jumpin’ Jerusalem, a party with girls!”

Even worse, just as he’s going to get ready, with a focus stealing one-legged hop up the staircase by the phone so loud his mother can barely hear the line, Mrs. Hardy takes a call from Mrs. Benedict and agrees that Andy will escort young Polly to the party. This really sets Andy off as he hasn’t seen Polly since Kindergarten and has no interest in having her hang all over him at this point in his life. Well, Andy changes his tune when Polly receives him, though I’d say the viewer is left about as drained in the face as Andy is, but for different reasons. When the door opens there’s no Ann Rutherford but instead an actress named Margaret Marquis, who the IMDb credits with a bit part in Ah, Wilderness!, welcoming Andy back into her life. While Rutherford would go on to play Polly Benedict in a dozen following Hardy features, I must admit Marquis does a good job of establishing the character, as other than appearances she’s every bit of Polly in attitude and character.

The overall tone of A Family Affair is mixed, ranging from Andy’s good times to Joanie’s troubles with the Judge’s aqueduct dilemma keeping things pretty even in between. There’s even a chase scene of sorts in A Family Affair, which because of the general un-Hardy like feel of the proceedings left me on the edge of my seat to some degree wondering what was going to happen! Marion and Wayne have pulled over to quarrel and discover that they’re out of gas. When Wayne manages to get a pair of obviously loaded passers-by to agree to tow them by rope to the nearest service station, the drunkards soon forget that Marion and Wayne are tied to their rear! A truck that’s lost it’s breaks suddenly cuts out of a side road behind them and we have all three vehicles racing around hair pin turns and narrowly avoiding each other and other obstacles. The scene feels like it’s meant for laughs, but at the same time there’s so much potential for violence that I half-expected tragedy.

The two drunks in the lead vehicle may have had the laugh out loud line of A Family Affair when one asks What time is it? and the other replies I-da-ho.

Back to the aqueduct, because it is the main conflict of A Family Affair. The no good Nichols originally brought his complaint to the Judge who saw enough merit in it to grant a temporary restraining order against construction. Judge Hardy is immediately confronted by the builder Mr. Wells (Selmer Jackson), editor of another Carvel paper Frank Redmond (a surly Charley Grapewin) and his own campaign manager, Oscar (Harlan Briggs), who are all in an uproar over his plans to halt the building. They tell the Judge that the construction will be a boon to the Carvel economy and the aqueduct itself is only going to send Carvel’s excess water to needier outlying cities.

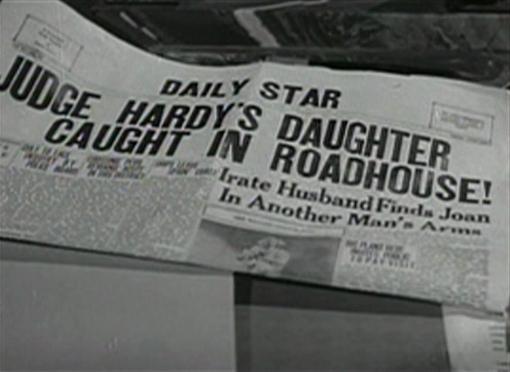

Something about the plan rubbed Judge Hardy wrong and he refuses to lift the restraining order despite the threat of political opposition at the nominating convention for the first time in the Judge’s twenty years on the bench. While Barrymore lacks the cool demeanor with which Lewis Stone would confront such a threat the end result is the same, he refuses to budge until he investigates further and will only do so then if the plans prove up to snuff. When an aggressive Charley Grapewin gives the Judge a taste of tomorrow’s planned headline–“Judge Hardy’s Daughter Caught in Roadhouse!”–the Judge really has to spring into overdrive and in doing so leaves us with a happy ending in every corner of A Family Affair.

A Family Affair was produced in just 17 days, directed by Hardy regular George B. Seitz for MGM, and successful enough to leave the public immediately clamoring for more. Of the casting Thomas Schatz writes in The Genius of the System that “Barrymore was too important an actor to be tied up with a series; MGM also had bigger plans for Byington.” I should note that within a year Barrymore was playing Dr. Gillespie in the first of the Dr. Kildare series, a part he’d recreate fifteen times himself in further Kildare/Gillespie movies between 1938-1947, so I’m not quite sure how enamored MGM actually was with their aging lead’s prospects just a year earlier.

The Andy Hardy character would be enlarged as soon as the second Hardy film, You’re Only Young Once (1937), and would grow to become the center of the series, the name even appearing in the title ten times beginning with fourth entry Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938). Rooney, who appeared in over two dozen films between A Family Affair and 1941, including popular non-Hardy titles such as Boys Town (1938) and its 1941 sequel, Men of Boys Town, paired with Judy Garland in Babes in Arms (1939), and in the title role in Young Tom Edison (1940), would celebrate the first of three consecutive years as Hollywood’s top box-office star beginning in 1939. Not to shabby for a young man who ranked behind both Freddie Bartholomew and Jackie Cooper on MGM’s talent chart prior to A Family Affair!

Coming next: MGM’s Hardy Family Series #2 – You’re Only Young Once (1937)

[…] Cliff from Immortal Ephemera is back again with a look at one of Rooney’s greatest performances: The Human Comedy. Cliff also has included links to two older pieces he wrote on Rooney’s performances in Death on the Diamond and A Family Affair. […]