I’ve included an expanded article about Child of Manhattan in my eBook Classic Movie Monthly #1

If you’re coming to this because of Preston Sturges, hopefully the engaging performance of Nancy Carroll keeps you from being too disappointed. Child of Manhattan is based on a play by Sturges that wasn’t exactly a flop (it ran for 87 performances on Broadway), but leaves you hard-pressed to find a critic saying anything nice about it back in 1932. The play took a critical drubbing at a time when Sturges the playwright really needed a success. Instead it drove him to Hollywood where he worked as a screenwriter through the remainder of the 1930s before beginning to establish his legendary directorial career with The Great McGinty in 1940.

If you’re coming to this because of Preston Sturges, hopefully the engaging performance of Nancy Carroll keeps you from being too disappointed. Child of Manhattan is based on a play by Sturges that wasn’t exactly a flop (it ran for 87 performances on Broadway), but leaves you hard-pressed to find a critic saying anything nice about it back in 1932. The play took a critical drubbing at a time when Sturges the playwright really needed a success. Instead it drove him to Hollywood where he worked as a screenwriter through the remainder of the 1930s before beginning to establish his legendary directorial career with The Great McGinty in 1940.

Child of Manhattan caused critics to torpedo Sturges on multiple fronts: 1) For a too transparent attempt at cashing in on a Hollywood adaptation (which backfired when Sturges lost the rights as collateral on a loan), 2) For lewdness, which helps it play well on any pre-Code bill today, even if it is pretty tame on the whole, and 3) For its dialogue, especially that of Greenpernt’s own Madeleine McGonagle (Carroll), who’ll pass on that plate of ersters because she has an aperntment at some other jernt. Catch my drift?

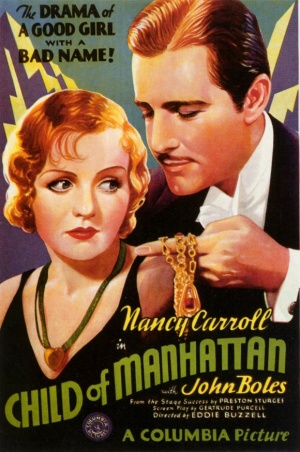

Even with Nancy Carroll’s boundless charisma those exaggerated New York inflections begin to feel forced and are overused to such an extent that their early charm wears off for everyone except leading man John Boles.

Carroll is Madeleine, the thoughtful taxi-dancer that New York millionaire Paul Vanderkill (Boles) lucks into upon entering Loveland, a dance club that rents its space on Vanderkill family property. Paul, a widower, has volunteered his services to his Aunt (Clara Blandick) to make sure Loveland isn’t too scandalous a property for the family portfolio. He falls hard for Madeleine, largely charmed by her speech, but also for her kindness after she misunderstands him and suspects that he’s hard-up. The contrasting manners and speech of the two romantic leads are based on an actual incident in playwright Sturges’s life that provided the initial spark for his play.

It takes a thousand-dollar tip—which earns a hell of a smack from her mother (Jane Darwell)—for Madeleine to understand who Paul really is. Paul soon declares his love for Madeleine, but he refuses to marry her because he wants to protect his daughter (who we never see) from scandal. Madeleine is just as hooked on Paul, and the next scene finds her being tossed out of the family apartment by her mother. For good measure her brother (Garry Owen) calls her a tramp on her way out the door. Those of you coming to Child of Manhattan for the early billed appearance by sixteen-year-old Betty Grable will be disappointed to discover that this is her only scene. Grable doesn’t do anything more than collapse onto a chair sobbing as her sister leaves forever.

An unplanned pregnancy causes Paul to relent and offer marriage. Madeleine, understanding how much Paul’s name means to him, is overcome by the offer, which she accepts. When their baby dies shortly after birth, Madeleine decides to seek out a quick and quiet Mexican divorce, but leaves without telling Paul of her plans.

Paul has no idea where she’s run off to until her ambitious divorce lawyer (Luis Alberni) appears in his New York office to have him sign papers that include a $100,000 per year alimony settlement. Money is the least of Paul’s problems, so he signs with the belief that Madeleine was just a very cagey gold digger. Back in Mexico Madeleine is distraught by what her lawyer has done. She zeroes in on a provision of the agreement that nullifies alimony payments if she were to remarry and decides this is the best way to correct her overzealous lawyer’s reach for Paul’s money. Her decision makes one of her old suitors, Panama Canal Kelley (Charles “Buck” Jones), very happy, at least until a Mexican bar brawl exposes Madeleine’s actual intentions to Paul back in New York.

Nancy Carroll became a major star in the late 1920s while mostly playing perky ingenues in lighthearted musical comedies. She opened eyes with her performance in the more dramatic The Shopworn Angel (1928) and received an Academy Award nomination for her work in The Devil’s Holiday (1930). The acclaim for that latter role provided more dramatic opportunities, though she often had to overcome bad casting decisions by her employer, Paramount. Stolen Heaven (1931) and Broken Lullaby (1932) are a couple of other gems you’ll want to check out. Carroll was loaned to Columbia for Child of Manhattan and impressed enough to receive a contract from them in 1934 after Paramount did not renew their agreement with her.

Likewise, John Boles first achieved stardom along a different route, rising as the leading man in early musicals like The Desert Song, Rio Rita (both 1929), and King of Jazz (1930). Director John M. Stahl put him to use as the leading man in melodramas Seed (1931) and Back Street (1932), and Child of Manhattan continued his string of leading men in so-called “women’s pictures.” If the label is at all accurate it may be for the way Boles disappears into the background when cast opposite strong actresses such as Irene Dunne and Nancy Carroll. The same can be said of later efforts alongside Margaret Sullavan in Only Yesterday (1933) and, of course, Barbara Stanwyck in Stella Dallas (1937).

Cowboy star Buck Jones makes a rare non-Western appearance in Child of Manhattan, though he’s certainly not miscast as the silver seeking Panama Canal Kelley of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Jones is hampered by some strange patterns of dialogue that I can only imagine drifted down from the original Sturges play.

Also on hand is 68-year-old Jessie Ralph, here billed as Jessie Rolph, in her first of many talkies. Ralph’s German-born Aunt Minnie watches over the girls at Loveland and later accompanies Madeleine to Mexico where she shares a funny scene with Jones and a bartender (Jack Kennedy).

While the opening scene of Child of Manhattan provides an interesting look at a taxi-dance hall, you’d do better checking out Stanwyck in Ten Cents a Dance (1931) if you’re looking for that flavor. This film is an interesting curio for Preston Sturges fans, but I think they’re mostly going to be disappointed, or possibly intrigued, by an immature, or at least incomplete, developing talent. No, the entire draw here is Nancy Carroll, superior to her material and alternately able to make you laugh with her natural charm and innocence or tug your heartstrings with her heartbreak and sacrifice.

Directed by Edward Buzzell for Columbia Pictures and released just before Valentine’s Day, 1933.

I don’t believe Child of Manhattan has ever been released on home video, but it has aired on Turner Classic Movies in the past (accompanying screen captures are from a copy I recorded when it did). I suspect, given its Columbia roots, Child of Manhattan also stands a chance of showing up on GetTV in the future.

I’ve included an expanded article about Child of Manhattan in my eBook Classic Movie Monthly #1

Leave a Reply