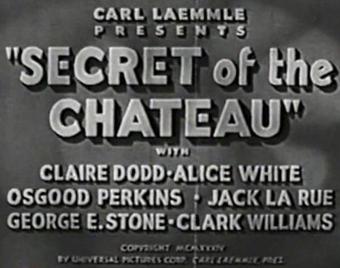

Secret of the Chateau is an effective murder mystery featuring several familiar faces, but no major stars. It’s reputation suffers because it was presented as a horror film, which it is not. At all. It tries to adapt the old dark house feel of Universal’s similarly titled Secret of the Blue Room (1933) and combines that setting with an attempt at the humor and deductive tactics found in MGM’s hit The Thin Man (1934). Secret of the Chateau’s French setting and its focus on a highly prized collectible is also reminiscent of Arsene Lupin (1932), where the Mona Lisa is targeted for theft. This movie doesn’t boast the Barrymores or Powell and Loy, but the cast is lined with favorites from the supporting and character actor classes, such as Claire Dodd, Jack La Rue, Ferdinand Gottschalk, Alice White, and George E. Stone.

Secret of the Chateau is an effective murder mystery featuring several familiar faces, but no major stars. It’s reputation suffers because it was presented as a horror film, which it is not. At all. It tries to adapt the old dark house feel of Universal’s similarly titled Secret of the Blue Room (1933) and combines that setting with an attempt at the humor and deductive tactics found in MGM’s hit The Thin Man (1934). Secret of the Chateau’s French setting and its focus on a highly prized collectible is also reminiscent of Arsene Lupin (1932), where the Mona Lisa is targeted for theft. This movie doesn’t boast the Barrymores or Powell and Loy, but the cast is lined with favorites from the supporting and character actor classes, such as Claire Dodd, Jack La Rue, Ferdinand Gottschalk, Alice White, and George E. Stone.

Secret of the Chateau is set around the world of rare books and features a killer bibliophile. The movie even opens at a rare book auction where top-billed Claire Dodd steals a valuable volume of Moliere from the hands of the winning bidder.

An aspiring painter (Clark Williams) visits the auction house to find out more about the pristine copy of the Gutenberg Bible he’s just inherited. He seats himself next to the attractive young book thief, Julie Verlaine (Dodd), who bolts the auction after falling under the familiar glare of Inspector Marotte (Gottschalk).

Julie and the young painter, Paul, engage in small talk about his Gutenberg Bible with Paul extending an invitation for her to come to his chateau and examine the volume. While he’s interested in selling the book, Paul is even more interested in Julie and the feeling seems to be mutual. Julie buys a painting from him for a hundred francs before making another quick departure that goes awry when she is immediately cornered by Marotte.

It’s revealed that Julie has recently completed a six-month prison sentence that Marotte pinned on her. The detective is now on the trail of a book thief and murderer who’s eluded him for the past decade. The rapier-tongued Inspector, who speaks of himself in the third person, hasn’t even managed to decipher if the killer is man or woman, which is why he remains interested in Julie. She gives Marotte the slip and scampers home where boyfriend Lucien (Jack La Rue) awaits.

Lucien is Julie’s partner in crime and is excited by her theft of the Moliere. He remarks that every time she pulls a new job he loves her even more, but Julie, looking uncomfortable, counters that she thinks less of herself after each new job. She’s fed up with this racket and with Lucien, who she breaks up with on the spot. Lucien’s response exposes a streak of jealousy and a violent temper, each intended to make us suspect he may possibly be the murderer Prahek. He tries to calm Julie down so he can tell her about her next job involving a newly inherited volume of the Gutenberg Bible. The volume Paul had just told her about. Julie refuses to go to the chateau, but Lucien seems rather sure that she’ll obey his wishes. She does not reveal she’s met the Gutenberg’s owner and has already secured an invitation.

Upon entering the chateau Julie runs into a huffy butler (Osgood Perkins) who soon escorts her into the office of cranky estate executor Bardou (DeWitt Jennings). Paul comes to Julie’s rescue before Bardou can kick her out of the chateau. Bardou has the Gutenberg Bible under lock and key with plans to donate it to a museum. He keeps it in a vault alongside a convincing reproduction that he’s had made to fool prospective thieves who make it past the screeching alarm. Paul wants to sell the book, but he’s not allowed to touch it for five years. His sour Aunt, Madame Rombiere (Helen Ware), who’s inherited half of the books, is also insistent about selling. Also on the premises are Paul’s obsessively neat friend, Armand (George E. Stone), and a wisecracking former admirer, Didi (Alice White), who teases Bardou in hopes of prying away the two thousand francs she feels she’s entitled too.

This group is eventually joined by a Professor Racque (William Faversham), who had made Paul an offer of 150,000 francs for the Gutenberg; Julie’s boyfriend Lucien, who arrives shortly before the first murder; and Chief Inspector Marotte, who is on the case the following morning.

This cast of ten-plus characters works very well together providing a fair share of quirks, phobias, and laughs. The weakest links are George E. Stone, a victim of poor material, though the weakness of his gags is more than made up for by Alice White’s cutting tongue, often sharpened at Helen Ware’s expense. Clark Williams also falls short as he lacks the leading man charisma required of his part. Old-timers Jennings, Gottschalk, and Ware all excel, as does Alice White. Besides her nastier interactions with Ware, White is great playing the flirt with DeWitt Jennings, who loses both his hairpiece and his watch down the front of her shirt. Dodd, who typically casts fangs at leading ladies from top supporting roles, handles her part well, though occasionally seems a little uncomfortable in such a sympathetic part.

The mystery holds up throughout with practically everybody except Gottschalk, Dodd, and Williams arousing suspicion. Gottschalk’s egotistical detective provides many chuckles and despite his small stature makes for an intimidating presence who seems more than capable of eventually deducing the villain.

A nice twist is provided when it turns out everybody is a murder suspect except for the person who stole the Gutenberg. The two incidents took place at the same time on different levels of the chateau so they had to be done by at least two different people. An additional curve eliminates one of the biggest red herrings by also absolving the thief of the counterfeit volume. A rare but mild disappointment comes in the actual reveal of the murderer, a bit of a cheat even if I didn’t see it coming myself. PS: Don’t read the IMDb credits because it doesn’t take Marotte’s deduction skills to figure out the killer from there.

When I wrote about Arsene Lupin I took time to research the actual theft of the Mona Lisa, so I wanted to see if there was any special reason for moviegoers to be fascinated by the Gutenberg Bible at the time of Secret of the Chateau. Sure enough, there was. On July 3, 1930 the Library of Congress purchased a large collection of early printed work that included a perfect three-volume edition of the Gutenberg Bible. Cost to taxpayers: $1.5 million for 3,000 pieces total. More on that expenditure, including what happened to a large share of the proceeds, is detailed below.

Secret of the Chateau has never had a home video release, though in this age of manufactured-on-demand DVD-R releases we can hold out hope that Universal will eventually put it out as part of their Vault Collection. For now gray market copies can be had, seek them out through the FindOldMovies search engine (iOffer listings recommended).

Not a ton of coverage out there about Secret of the Chateau, but I enjoyed this take over at Classic Film Freak.

Also recommended is the entry in the classic Universal Horrors, which should be on a nearby shelf for all fans of old horror movies. Which, again, this really isn’t.

Historical Aside:

U.S Government Inadvertently Funds Nazi Propagandist Through Gutenberg Purchase

I was sidetracked from this review for a good six hours because of the fascinating circumstances surrounding the 1930 Library of Congress purchase of the Gutenberg Bible. My headline is a bit of a spoiler, but it’s still a shard of Depression-era history that I wanted to get down while it was fresh in mind.

In the mid-1920s Dr. Otto H.V. Vollbehr arrived in America from his native Germany and began making headlines for his discoveries and purchases of rare 15th century incunabula (Defined by AbeBooks as “a book, pamphlet or other document that was printed, and not handwritten, before the start of the 16th century in Europe.”). He was hailed a great benefactor upon presenting the U.S. Library of Congress with a collection of fifteenth and sixteenth century printer’s marks. Later it was remarked that these items were then only worth “a dime to a dollar each.” But Vollbehr’s gift brought a bookman national celebrity at a time when bookmen were claiming their fair share of press through fabulous sales. Pre-Depression trade peaked in a January 1929 rare book auction that grossed $1.8 million. The rare book trade was booming, until the Crash.

Dr. Vollbehr had a collection of incunabula totaling 3,000 pieces including what was far and away the top item of the bunch, his Gutenberg Bible. Never mind that this copy of the Gutenberg still belonged to an Austrian monastery, Vollbehr deemed it centerpiece of a collection he was offering in whole for a mere three million dollars. After Harvard turned him down at that price Vollbehr offered the entire collection, except the Gutenberg, to a Chicago Cardinal for $200,000, but that deal didn’t happen either. Vollbehr then decided to make his collection “a gift” to the Library of Congress, all for the token fee of $1.5 million. A bill passed through both Houses of Congress authorizing the sale and President Hoover signed off on the purchase on July 3, 1930, just over eight months after the Stock Market had crashed.

There was some controversy in the immediate aftermath of the sale because the monastery still held the Gutenberg and Austria wanted a fresh export permit after learning that it was to be transferred to the U.S. government. But by September 1930 the volume was reportedly in the hands of the U.S. librarian of Congress, or more accurately sealed inside a zinc-lined trunk within his office. Vollbehr had secured the volume for a figure reportedly ranging between $300,000-$375,000, the exact number likely depending upon that final tax from Austria. The book was appraised at $600,000 at that time which, even if accurate, makes the overall deal a head-scratcher since the other 2,999 items had previously been offered to that Chicago Cardinal for just $200,000.

There’s no doubting that the U.S. government had secured some treasures, but there’s just as little doubt that they had overpaid in 1930 dollars.

Dr. Vollbehr continued to pop up in the book news from time to time, but began making waves on other fronts in 1934.

Vollbehr returned from a trip to his native Germany with kind words for Hitler in a Los Angeles Times interview: “America must do as Germany did, stamp out Communism, which had all but destroyed Germany when Hitler came into power and freed the German people of Moscow domination and its thousands of paid agents.” Before the year was out Vollbehr was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities where he admitted he’d been distributing Nazi propaganda and anti-Semitic documents to U.S. schools and colleges. A specific example recalled his spending $5,000-$6,000 to mail a series of pamphlets titled “Hitler’s Memoranda” to American schools. In 1937 Representative Dickstein of New York listed him on the Congressional Record as one of 46 people described as “expert spies and agitators.” Dickstein’s listing referred to Vollbehr as a “Nazi propagandist and anti-Semitic writer.”

Vollbehr traveled back and forth between the U.S. and Europe numerous times throughout the 1930s buying and selling rare books. The old newspapers last placed him in America in 1938, when he attended several parties at Montauk on Long Island. He then returned to Germany, where he died in 1946.

Burton Rascoe published a Vollbehr expose in the May 18, 1940 edition of the Saturday Review of Literature. In his article, “Uncle Sam Has a Book,” Rascoe writes of the Gutenberg sale, “Nearly all of the net proceeds of the $1,500,000 sale … was spent in the United States by him [Vollbehr] for the dissemination of pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic propaganda!” Rascoe delves into the history of Vollbehr’s business activities in the U.S., specifics of the Library of Congress sale, and Vollbehr’s subsequent involvement in pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic activities on U.S. soil. Rascoe’s piece covers most of the information that I’ve included in this section, though I’ve also chased down other original sources that you’ll find cited below.

Vollbehr References

- “Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia. STANFIELD Et Al. v. VOLLBEHR. 60 F.2d 670 (D.C. Cir. 1932).” Casetext. May 16, 1932. https://casetext.com/case/stanfield-v-vollbehr.

- “Dickstein Lists 46 as Spies and Agitators.” New York Sun. 27 July 1937, 32.

- Friedheim, Eric. “Sift Activities of Reds and Fascists.” Syracuse Journal. 17 December 1934, 9.

- “Gutenberg Bible Kept Under Lock.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 15 September 1930, 26.

- “Nation Warned On Red Danger.” Los Angeles Times. 25 April 1934, A2.

- Rascoe, Burton. “Uncle Sam Has a Book.” Saturday Review of Literature. 18 May 1940. 3-4, 14-16.

- “Sale of Gutenberg Bible Is Opposed.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 20 August 1930, 2.

Note: New page on the site, Personality Index, collects all personalities tagged in more than one article on Immortal Ephemera. I think it’s pretty cool, check it out: Personality Index.

Leave a Reply