Bad Reception but Better With Age

Critics didn’t care for Panama Flo when it was released in early 1932.

Critics didn’t care for Panama Flo when it was released in early 1932.

Film Daily said, “this melodrama carries a story that is nevertheless so weak in spots that even the most gullible will find it unconvincing.” Photoplay complained that none of the capable cast members, “can rise above the inconsistencies of the characters and the trite dialogue,” and those top three stars, “deserve meatier stuff.” Picture Play even knocked some of Helen Twelvetrees’ past work claiming, “The plot of this one is too involved to go into here … The picture is better than most of her recent ones, which isn’t saying much.” They did then make an accurate comparison stating, “It is an obvious attempt to recapture the dramatic tang of Her Man.”

While none of that is entirely inaccurate, even if a bit too mean-spirited in spots, I thought Panama Flo was a title that deserved a much heartier recommendation today then it received back in ‘32. New York Times film critic Andre Sennwald nails what I liked best about Panama Flo in this comment, even if his intention was to further cast the movie in a negative light:

“The story offers all the coherence, credibility and realism of a hasheesh dream, and it managed to confound a startled audience last night right down to the fade-out …”

Panama Flo captures the hardboiled spirit of 1932, a dark side not so easily enjoyed in that time itself. For most viewers Panama Flo’s most familiar visit to the wrong side of the tracks comes in the New York speakeasy portion of the story that frames an even more morally objectionable flashback. Moving back in time we first join Flo (Helen Twelvetrees) as she sings and dances with a line of girls in a Panama honky-tonk before circumstance forces her south for a more extended stay in the dense jungles of South America where she is more or less a captive of wildcat oil man McTeague (Charles Bickford).

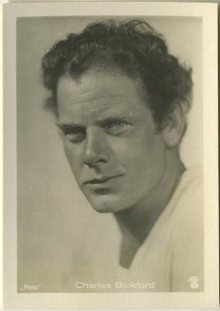

Bickford is more wildman than wildcatter as he-man McTeague. Sporting a permanent scowl Bickford’s poor temper keeps the volume of his voice at about three times that of the other characters. He breaks furniture during tantrums and makes sport of breaking liquor bottles. He’s rude, crude and vows that, “Some day I’m gonna be the richest guy in South America.”

Sennwald referred to him as, “the terrible McTeague, alias the King of South of America.” But in this 1932 programmer, which came and went so fast that I can’t locate poster art better than a few unimpressive newspaper ads, Bickford’s boisterousness becomes a camp attraction that adds an extra element of fun to a forgotten film whose parts are greater than its whole.

On a similar score, how about that lingo? Overlooked if not openly scorned jargon and slang in its time, lines like these are priceless treasures for the viewer today:

“He’s got a roll that will choke a walrus.” — Sadie (Maude Eburne) on McTeague’s bankroll.

“Everything goes here these days, huh? Mickey Finns and lifting rolls.” — McTeague to Sadie when the jig is up.

“C’mon, snap out of it. You pulled a phony, now you’ve got to pay for it.” — McTeague to Flo, when she can’t make proper restitution.

“So this is geology, is it? Well I’ll take a baked apple.” — Flo to McTeague after he tries to explain geology to her. (I’m still trying to figure out that baked apple!)

“One of these days I’m gonna be King of South America. You can be Queen,” McTeague says, taking Flo’s arm.

“You’re gonna get crowned right now if you don’t stop pawing me.” — Flo’s reply.“Say listen, sweetheart, anyone smart enough to walk off with a million bucks is no crook. He’s a financier.” — Babe Dillon (Robert Armstrong) to Flo.

“That’s my car and it belongs to my daddy.” — Flo to McTeague, definitely not speaking of her father.

Despite polar opposite acting techniques displaying a Bickford who seems to be speaking to the last row in the theater and a Twelvetrees who would have been a wonder on the silent screen as her beautiful features always manage to express just the right emotional note, these two personalities manage to spark with one another. Bushy haired Bickford with a face chiseled from rock towers over petite Twelvetrees who looks as though she’s going to break whenever he grabs her.

Grab her he does, with an extra bit of force, after she takes part in a plot to fleece him of his bankroll. He drags her out of Sadie’s Place into the streets.

“You’re breaking my wrist,” she screams.

“You’ll get more than your wrist broken if that dough ain’t there,” he says, refusing to break his grip as he drags her to her partner-in-crime’s apartment.

He does pause once. In front of the jail. “You see that? You know what that is? That’s the hoosegow. That’s where you’re going later,” he says.

She pleads for mercy but McTeague is a hard man. “All this hearts and flowers stuff ain’t getting me back my bankroll,” he says.

“Sending me down there with all those filthy men won’t bring it back either.”

With McTeague’s money gone and Flo the only culprit on hand for reprisal, she has no choice but to agree to go with him to South America to serve as his housekeeper.

She only asks one thing: “You gotta promise not to–” She can’t look at him. Flo lowers her head, shamed by the possibility, and adds, “Get rough.”

Helen Twelvetrees

Beautiful Helen Twelvetrees is every bit as natural throughout Panama Flo as Bickford is over-the-top. Picture Play had got it right, except for the judgement on quality. After Twelvetrees scored in 1930’s Her Man she repeated the same role time and again for Pathe and then RKO Pathe.

She was the good girl who had to overcome bad circumstance. Bad circumstance usually meant men.

Looking at it from the producer’s standpoint it was a good decision: The formula worked and it made money. After Her Man Twelvetrees repeated her act in the better remembered Millie (1931) shortly before Panama Flo. Her movies are a bit hard to find today, but another good one fitting the type is My Woman (1933) for Columbia, which I wrote about a while back HERE.

Understandably Twelvetrees had a different opinion of the parts she played during what turned out to be her relatively brief Hollywood career, which included just over 30 films between 1929 and 1939. When asked in 1955 if she missed movie acting Twelvetrees replied in no uncertain terms: “I was completely fed up when I left Hollywood — with my roles, with my life.”

The Brooklyn born and bred Helen Twelvetrees, by then an Air Force wife accompanying her fourth husband, Major Conrad Payne, around the world, realized that her greatest talent was her curse in Hollywood.

“You see, they found out right away that I could cry real tears in a well written situation. No glycerin stuff, but tears. So they turned me into a weeper, which seems funny because I never was a crier … But I wept my way along for years—in rags, in satins, abandoned, deserted—I just kept weeping along. I finally ran out.”

She was born Helen Marie Jurgens, Christmas Day, 1907.

She had acted some in school, but cast that interest aside for the fine arts and attended the Art Students’ League in Manhattan. While there her instructor, George Bradshaw Crandall, received a commission to paint a cover for the Saturday Evening Post. While the cover of the Post was dominated by Norman Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker throughout the twenties, other artists occasionally slipped in as Crandall did sporadically throughout the decade. The beauty on the cover caused a bit of a sensation as more than one stage producer contacted the artist to inquire about the identity of his model.

Based on the timing of Helen’s biography and the fact that none of Crandall’s other Post covers of the period resemble her, I believe that the October 23, 1926 cover shown on this page is the one which served to spark Helen’s renewed interest in acting and, more importantly, the interest in her.

Based on the timing of Helen’s biography and the fact that none of Crandall’s other Post covers of the period resemble her, I believe that the October 23, 1926 cover shown on this page is the one which served to spark Helen’s renewed interest in acting and, more importantly, the interest in her.

While Helen’s family first opposed her desire to act, they relented when she agreed to enroll at the American Academy of the Dramatic Arts. It was likely there that she met her first husband, Clark Twelvetrees. Her husband took work with Stuart Walker’s Stock Company in Cincinnati on condition that there was work for his wife as well. It was Clark who went to Chicago hoping to land a part in An American Tragedy, but it was Helen who emerged with the socialite role that was originated on stage in New York by Miriam Hopkins.

Their marriage was strained by the time Helen landed a film contract with Fox in 1929. She and Clark were divorced in April 1931 and later that same month Helen married for a second time to Jack Woody, a Beverly Hills real estate man. She was Mrs. Woody at the time of Panama Flo although she was billed as Helen Twelvetrees for the remainder of her career. Helen had a child by Woody in 1932, but the two divorced in 1936.Her final movie was Paramount’s Unmarried in 1939. She returned to the stage taking a lead role in The Man Who Came to Dinner with a U.S.O. troupe and was reported to have met fourth husband Payne when the show reached Oberstdorf in the Bavarian Mountains. Cythia Lowry’s 1955 AP report claims they were married in Paris just five months after they met.

“I’m very lucky,” Helen told Lowry. “If something happens tomorrow I know that I’ve had the happiest nine years a woman could have,” she said, referencing her marriage. “Go back to acting? Oh, I’ve thought it might help fill in the time until my husband gets back and we can be together again—but that’s all.”

Unfortunately Helen Twelvetrees was ill. She had supposedly been suffering from a kidney ailment for some time before her death, which was caused by an sedative overdose that wound up being ruled a suicide. Helen Twelvetrees died February 13, 1958. She was fifty-years-old.

Panama Flo

After McTeague tracks Flo down in a New York speakeasy Panama Flo flashes back to tell the tale that has led them to this uncomfortable reunion.

Those were happy enough times for Flo, singing and dancing with a group of girls at Sadie’s Place in Panama while her boyfriend, Babe Dillon (Robert Armstrong), sat and watched.

Luck turns quickly though when Sadie (Maude Eburne) decides to fire the girls because they’re not bringing in enough cash. In addition to losing the paying gig Sadie won’t pay to send them back to New York. Flo objects, stating that was in their agreement. “So sue me,” Sadie tells her.

Boyfriend Babe pops his head in next. “I’ll keep my eyes open for some heavy sugar, girls” he says after learning they’ve all been canned.

Later that night Babe tells Flo he has to leave Panama for awhile. Babe works as a aerial photographer for a syndicated newspaper and has been ordered down to the Amazon to take some shots. When Flo suggests they get married that night so she can come along he tells her that he already has someone from the military filling the passenger seat of his two-seat plane.

Babe is gone longer than expected. Flo runs out of money and Sadie runs out of charity. Not that Sadie doesn’t like the younger girl. When Dan McTeague bounds in flashing his bankroll Sadie convinces Flo to use the situation to her advantage.

This is Flo’s first time taking part in a con like this and her inexperience winds up getting her caught. That leads to the eventual agreement of her accompanying McTeague to South America to work off her debt as his housekeeper.

McTeague sends away his native girlfriend, Chacra, played by Lupe Velez’ sister, Reina Velez, in her only film, and plants Flo inside his house in her place. Flo realizes what McTeague wants from the start so she quickly takes possession of a gun she spots when he’s not looking and, sure enough, that first night together she has to hold him off at gunpoint from her bed. She even fires a warning shot just past McTeague!

Flo and McTeague soon settle into an uncomfortable life together where neither is really getting what they want. Flo is plagued by the heat and the insects and McTeague tries to curb his sexual frustration by drinking himself into a stupor each night.

One evening McTeague gets Chacra to steal Flo’s gun when she isn’t looking. Charmer that he is McTeague thanks the native girl and then points to the jungle. “You see that jungle?” he asks. She nods. “Well, scram. Beat it. If I catch you hanging around here anymore I’ll string you up by the thumbs.”

In a few moments McTeague corners Flo into a dance. She objects when he cuts off the music but he says, “We don’t need music now. We ain’t gonna dance anymore.” He picks her up in his arms and barely notices her pounding at his face and chest. Just as he reaches the bedroom door the jungle silence is broken by the sound of a plane roaring overhead.

“Dillon’s the name,” Babe says, greeting McTeague. “Can you put me up for the night?”

“If I got to,” comes the cheery reply.

Babe tells Flo to pretend she doesn’t know him. They plan an escape but all three characters face some surprises on the way to a creative ending to the South American flashback. What happened there, once fully revealed in our New York speakeasy a few years after the deed is done, actually winds up anticipating the ending to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

This final section of the film includes an outraged Flo in some of Twelvetrees’ best scenes before a conclusion that is left more open than I’m used to with movies of this period. But it is an ending that does provide more than a little hope that the guy gets the girl once we’ve left the theater.

Production and Personalities

Film Daily called Garrett Fort “one of the busiest writers on the Coast” in their issue of July 13, 1931. At that time they reported that the Frankenstein screenwriter was then busied by daily conferences with James Whale wrapping up that project at Universal, but that he would return to RKO Pathe the following week to finish up work on The Second Shot.

The Second Shot became Panama Flo by the time it entered production in the Fall.

A former stage actor, 36-year-old Ralph Murphy, was chosen to direct Panama Flo. It was only the second movie he directed though he had previously worked on the screenplay for the Helen Twelvetrees hit Millie. Murphy was a Hollywood director from that time through 1952, and on television after that, though not many of his films are familiar today.

Murphy may be best remembered as Gloria Dickson’s ex-husband, but they had divorced a little less than a year before 30-year-old Dickson died in a house fire.

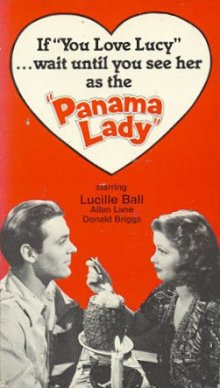

Panama Flo opened in New York, January 19, 1932, and nationwide ten days later. It received those less than impressive reviews referenced at the top of the page and quickly disappeared for several years before being remade as Panama Lady starring Lucille Ball in 1939.

Panama Flo opened in New York, January 19, 1932, and nationwide ten days later. It received those less than impressive reviews referenced at the top of the page and quickly disappeared for several years before being remade as Panama Lady starring Lucille Ball in 1939.

Panama Flo has never been released on video and even the remake starring the iconic Lucy has only ever had a VHS release that is now long out of print and fetching top dollar on the reseller market. At the time of this writing the original Panama Flo had recently aired on Turner Classic Movies and could be viewed in its entirety on YouTube.

A little over a year after the release of Panama Flo Robert Armstrong would enjoy his greatest success as Carl Denham in King Kong. Armstrong, whose show business roots came courtesy of his uncle, playwright-producer Paul Armstrong, trasitioned from stage to screen in Pathe’s The Main Event,a silent drama released late in 1927. Of the three stars of Panama Flo he is the weakest, but his part turns out to be rather thankless, especially considering the long absence he takes after being first introduced.

Just over forty at the time of Panama Flo, Charles Bickford’s best days already seemed to be behind him.

Just over forty at the time of Panama Flo, Charles Bickford’s best days already seemed to be behind him.

He had responded to a film offer from Cecil B. De Mille which lured him from the stage to appear in Dynamite (1929). That turned out to be a lousy experience for both men as Bickford wound up punching out the famed director during production.

The burly actor caught a break when MGM cast him in Anna Christie (1930), the movie where Garbo talked for the first time and Bickford became a star in her wake. But he didn’t get along with Louis B. Mayer and when another offer came along Bickford asked out of his contract. Mayer obliged and the other offer then disappeared.

Bickford became an independent actor and slowly faded into obscurity. Later he’d have a fine second act as a character actor, most famously in The Farmer’s Daughter (1947), but that’s fifteen years removed from Panama Flo and another story.

Returning to the AP story that caught up with Helen Twelvetrees in 1955, Cynthia Lowry wound up her piece writing, “The only thing she really worries about is that some of those dreadful old weepers will be coming back on television.”

Returning to the AP story that caught up with Helen Twelvetrees in 1955, Cynthia Lowry wound up her piece writing, “The only thing she really worries about is that some of those dreadful old weepers will be coming back on television.”

“Oh no,” said Helen. “Anything but that.”

Not to worry, Miss Twelvetrees. Time has been kind. Unfortunately since you were never cast in anything major, no classic that has sustained its popularity over time, you are unfairly forgotten. But with a few better known titles there would be no reason for Helen Twelvetrees not to be remembered as well as fellow screen sufferer Sylvia Sidney.

Of the few Helen Twelvetrees titles I have been able to see it is very hard not to leave her movies without her providing the most memorable performance and emerging as a favorite.

Anything but that, she had pleaded. I’m sorry to disobey, but my advice is not to miss any movie featuring Helen Twelvetrees.

Sources:

- Blair, Harry N. “Helen Twelvetrees: Champion on the Bike.” The New Movie Magazine 1931 Jan: 16.

- Lowry, Cynthia. “For Nine Years No Tears After Long, Briny Career.” Daytona Beach Morning Journal 1 Aug 1955: 2. Google News. Web. 14 Mar 2013.

- Sennwald, Andre. “Panama Flo.” The New York Times 20 Jan 1932. New York Times Archives. Web. 14 Mar 2013.

Note: All news and reviews quoted from Film Daily, Photoplay and Picture Play magazines come from the Internet Archive’s holdings as accessed via the Media History Digital Archive.

Leave a Reply