Freddie Bartholomew in Brief

Child star Freddie Bartholomew was born Frederick Cecil Bartholomew on March 28, 1924 in Willesden, Middlesex, London, England to parents Cecil Llewellyn and Lillian Mae Bartholomew. They would soon put him under the care of his aunt, Millicent, his father’s sister, who had the talented young Freddie reciting on the stage as early as age 3 before he was eventually cast in some small parts in early 1930’s British film productions.

Freddie’s rise to fame came as Millicent, called Cissie by Freddie and soon the worldwide press, ushered him off to America to star in David O. Selznick’s production of David Copperfield (1935) at MGM. Freddie’s instant success led to his parents regaining interest in his custody and several Bartholomew vs. Bartholomew court battles primarily over money for many years afterward.

Meanwhile, Freddie Bartholomew solidified his box office standing as second to only Shirley Temple among child stars starring in classics such as Anna Karenina (1935) with Greta Garbo, Little Lord Fauntleroy (1936), Captains Courageous (1937) with Spencer Tracy, and several other minor classics of the 1930’s.

After the success of Captains Courageous, Freddie tried to get an increase in salary from MGM but this action just led to suspension and a critical year away from film. Freddie’s screen popularity dwindled as the young man grew taller and it would take a major hit when World War II saw him take another extended absence from the screen. Bartholomew only served a year before being discharged due to a back injury, returning to Hollywood in January 1944 as an American citizen.

Freddie’s screen career was all but over and he spent the remainder of the 1940’s on small stages across America and, briefly, in Australia. One such early project led to the first of three eventual marriages, but that first union would cause a split with Aunt Cissie who soon returned to England. By 1949 he had returned to America and began a new career in television, not in front of the camera, but behind it as TV director at WPIX in New York.

By 1954 Bartholomew was working for the Benton & Bowles advertising agency where he would eventually rise to Vice-President. Fred C. Bartholomew last gained some mention in the press in the early 80’s as executive producer of a few of the more popular soap operas on network TV. He’d soon retire to Florida where he’d live out his final years before succumbing to emphysema at age 67, January 23, 1992.

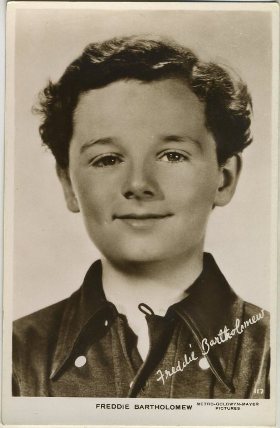

Settle in and keep reading below the following Freddie photo for the long version!

Introduction

This biography of Freddie Bartholomew is not yet complete. That said it is the most complete biography ever written about him.

I began researching Freddie Bartholomew for what was intended as a short blog post. I became more intrigued by the subject when I quickly spotted errors in his 1992 New York Times obituary. This was the Times after all and the facts were obviously wrong! What’s worse, over the next couple of decades those inaccuracies were passed down across the Internet and even into print books.

From there I became obsessed with mining as much information as I could about the former child star and I am pretty certain that as of this publication I’ve scoured every available source about Freddie Bartholomew. Some mysteries remain. But isn’t that always the case?

Before the biographical puzzle came the films. As one who normally accepts the presence of child stars as a necessary evil just what was it that drew me to the work of Freddie Bartholomew?

Before the biographical puzzle came the films. As one who normally accepts the presence of child stars as a necessary evil just what was it that drew me to the work of Freddie Bartholomew?

After extensive viewing of Freddie’s films over the past couple of years what I’ve most appreciated about him is that he doesn’t come across as a spectacle like many child stars. Rather than wishing he was your kid you wished that you were that kid again. Freddie Bartholomew behaves in a way that the adult can relate back to their own childhood, he recalls a nostalgia of experience rather than simply causing you to point and say look at the cute kid!

I think Freddie best accomplished this through the sense of wonder he brought to his characters. Rather than sing, dance or simply act cute, Bartholomew is always discovering.

He reacts to his often adult environment and despite the occasional outbreak of tears he must come to cope with serious problems in realistic ways. Not coincidentally some of his best reactions come when paired with the courser Mickey Rooney, who’s typically introducing Bartholomew to the ways of American youth.

I don’t think the charm of Freddie in his classics such as David Copperfield, Little Lord Fauntleroy or even the brattier Freddie of Captains Courageous comes from the viewer simply observing him–I find that more than any other child star we’re walking in Freddie’s shoes in these films and experiencing the world as he experiences it.

Freddie Bartholomew

With only a handful of British film credits to his name Freddie Bartholomew exploded to stardom in his first American film, David O. Selznick’s production of David Copperfield for MGM in 1935. The interruption of World War II timed with Freddie’s growth spurt into adulthood would just as quickly push Freddie’s career off a cliff. Despite several postwar attempts to recapture his earlier successes Freddie Bartholomew’s path would eventually lead to other careers off the screen.

After sifting through all of the available information my general thought is, yes, we’ve heard a lot about child stars having it tough but little Freddie Bartholomew had it rougher than most.

After sifting through all of the available information my general thought is, yes, we’ve heard a lot about child stars having it tough but little Freddie Bartholomew had it rougher than most.

He was paid and paid well. Or at least the Freddie Bartholomew name was paid–after Captains Courageous Freddie’s paycheck would be $2,500 a week or $98,000 annually depending on how the numbers were presented. This salary was second only to mega moppet Shirley Temple among child stars.

But not only did Bartholomew not see anywhere near as much of his fortune as he should have, he had to go to court over two dozen times to do battle with his parents over not just his earnings, but other aspects of his life and livelihood as well.

Freddie Bartholomew was one of the most popular movie stars alive from approximately 1935 to 1940. But he was not yet an adult. Had he been he could have had the type of movie star life that is often dreamed of. Freddie’s finances became public because of his legal entanglements. One release of his bank figures put his savings at $1,800 at the time of his Captains Courageous raise. Much more than most Depression Era teenagers no doubt. But a movie star?

Nobody: not Freddie, not his parents, his two sisters, nor even his Aunt Cissie, saw as much money as the various lawyers involved on each side must have banked. And then there was Uncle Sam.

Freddie Bartholomew didn’t squander his fortune. He was an earning machine for everyone but himself.

Freddie’s parents, Cecil Llewellyn and Lilian Mae Bartholomew, 1936

Corrected Biography

The pre-MGM years of Freddie Bartholomew are the most uncertain, but one agreed upon fact is that he was born March 28, 1924.

The general consensus, apparently established by his 1992 New York Times obituary, has held that Freddie was born in Dublin, Ireland. I was never able to uncover the source information leading to this incorrect citation but the Times piece has been cited so often that Freddie even appears in books about Irish stars now. He doesn’t belong in them.

Freddie’s birth was registered in the Willesden Registration District in the January to March quarter of 1924. This would make Freddie Bartholomew’s place of birth Willesden, Middlesex, London, England.

Many modern sources also list Freddie’s birth name as either Frederick Llewellyn or Frederick Llewellyn March, adding that he didn’t take the Bartholomew name until coming under his Aunt’s care between ages 3 and 4. This implies that the Bartholomew name was either his aunt’s married name or his mother’s maiden name. Wrong again.

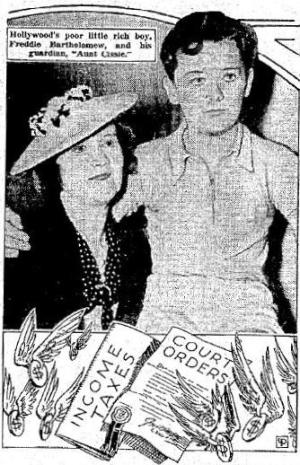

Freddie with his Aunt Cissy, 1937

My hypothesis is that some sources are confusing Freddie with either his father and/or his one-time early co-star, Frederic March to come up with these alternate incorrect names.

Freddie Bartholomew was born Frederick Cecil Bartholomew.

Freddie had two older sisters, Hilda, 2 years his elder, and Eileen, 2 years older than her, who were both raised by his parents, Cecil and Lilian Mae. Freddie’s talents would soon put him under Aunt Cissie’s care.

Show Biz Beginnings

These talents are said to have been first exposed to the public sometime between Freddie’s third and fourth birthday, approximately 1927, when he recited poetry at a Church social.

In Helen Hoerle’s 1935 biography of Bartholomew which is, mind you, a Big Little Book targeted directly at children with a very positive spin, Freddie developed into the local “Boy Wonder Elocutionist” while living at the Carlton Villa, his grandparents big home in Warminster.

Aunt Cissie also lived at Carlton Villa and it was she who would accompany Freddie about the area as he gave his recitations. Hoerle writes that Freddie began with nursery rhymes before progressing to the poetry of Winnie-the-Pooh author A.A. Milne and eventually portions of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice!

He eventually performed a number called the Toytown Artillery at a Concert Party in Warminster. For Toytown Artillery Freddie rode a make-believe horse while delighting the crowd with a song from atop it. This success led to an invitation to appear at a benefit for blinded soldiers at Wigmore Hall, a famed London auditorium. Hoerle credits that engagement for attracting the interest of the Gaumont Studio which led to Freddie’s film debut in the short Toyland for Gainsborough Pictures.

He eventually performed a number called the Toytown Artillery at a Concert Party in Warminster. For Toytown Artillery Freddie rode a make-believe horse while delighting the crowd with a song from atop it. This success led to an invitation to appear at a benefit for blinded soldiers at Wigmore Hall, a famed London auditorium. Hoerle credits that engagement for attracting the interest of the Gaumont Studio which led to Freddie’s film debut in the short Toyland for Gainsborough Pictures.

Hoerle’s account seems an idealized quick rise that leaves out the toil in deference to reimagined quotes of wonder from the young performer.

Hoerle is backed up by a mid-1930’s newspaper report that also claims by age seven Freddie was performing Shakespeare at benefits and concert parties.

Another account of Freddie Bartholomew’s earliest performing days comes courtesy of a 1976 letter by a P.Bond of Essex to the Daily Mirror. While the accuracy of these claims only go as far as you are willing to trust Mr. Bond, he said that Freddie had played the part of Tiny in a song and dance act performed around Warminster which saw himself, Mr. Bond, as a character named Lofty and their partner playing the part of Shorty. Bond says Freddie was just 4 at the time!

Aunt Millicent soon put him in the hands of Italia Conti, a specialist in training young actors who counted Noel Coward and Gertrude Lawrence among her trainees. Conti operated an Academy in her name which was founded in 1911 and is still highly respected today.

In a 1936 Liberty Magazine article Ring Lardner, Jr. wrote that young Freddie “has never appeared in a legitimate play, his appearances in England having been confined to benefits, concert parties, and to three motion pictures.”

In a 1936 Liberty Magazine article Ring Lardner, Jr. wrote that young Freddie “has never appeared in a legitimate play, his appearances in England having been confined to benefits, concert parties, and to three motion pictures.”

Taken as a whole these varied reports indicate a very active young performer beginning in the year 1927.

Freddie Bartholomew’s screen career started slowly in his native land. After the Gainsbourough short Toyland in 1930 his next film appearance came the following year in Miles Mander’s Fascination starring Madeline Carroll. Mander was also among the cast in Freddie’s next U.K. production, Lily Christine (1932), featuring former American silent screen star Corinne Griffith, trying to revive her career overseas, along with, fresh off of Frankenstein, Colin Clive.

Lily Christine received a lot of extra fanfare through the interest of the Prince of Wales, who even appeared at its premiere. Despite the extra coverage afforded Lily Christine accompanying reviews found the film lackluster at best. It was a flop. Freddie then appeared in one additional British short, Strip, Strip, Hooray, prior to his exploding to stardom in his next role in America.

Star

Researching Freddie Bartholomew’s peak years it quickly became obvious that there were two main themes to the period coverage: hit films and court battles. Of course, the hit films came first.

Like much of Freddie’s life his actual entry to America, where he would one day become a citizen, is a story requiring some dots be connected. Poring through numerous sources, what follows appears to be most accurate.

In attempting to cast the title role of David Copperfield

In attempting to cast the title role of David Copperfield MGM producer David O.Selznick cast a wide net eventually recruiting over 300 applicants. Of these only six children spoke cultured enough English to be seriously considered for the part. None of those six were even British, a more than minor detail which would surely tick off Mr. Dickens’ native country.

Selznick and director George Cukor are said to have spotted Freddie on a trip to England and were immediately sold on him, but selecting Freddie for the part was complicated by British immigration and child labor laws which forbade Freddie’s legally working in America.

The Daily Express explained it best when it reported “Aunt Millicent winked. She packed their bags and sailed for a holiday in Hollywood.”

According to later articles and testimony that is also similar to what Freddie’s parents thought: Aunt Millicent (Cissie hereafter) had taken Freddie on a two month vacation to New York. Well, Cissie and Freddie quickly found themselves in Hollywood where Freddie replaced the previously announced David Jack Holt in the part of young David Copperfield.

Selznick himself writes in the Rudy Behlmer edited Memo from David O. Selznick that Freddie and Cissie arrived in August 1934 “having come here with hopes getting title role David Copperfield, for which we thought him strong possibility.” Selznick writes that Freddie’s case was complicated by his father telling the British press that it was a done deal “falsely putting us in position of trying to violate English law against importation of children for labor.”

Selznick tells attorney Sol Rosenblatt that they can’t budge on production until gaining approval from the British government which costs the studio $1,000 daily, certainly Selznick’s own wink that Copperfield by then belonged to Freddie Bartholomew.

Soon after Selznick contacted MGM’s Managing Director in London, Sam Eckman, Jr., with the text to be released to the British press: “Freddie’s stage experience, plus charming personality and distinctly English manner of speech swayed opinion in his favor.” That manner of speech was key as Selznick had written Rosenblatt that the “English public would certainly resent seeing American child as David Copperfield.”

Soon enough Freddie’s parents would be using the word “kidnapping” in describing Aunt Cissie’s extraction of their son from British soil.

Copperfield, or more officially The Personal History, Adventures, Experience, and Observation of David Copperfield, the Younger, was an immediate hit upon it’s release in January 1935 and remains a critical success to this day.

Most of the praise is heaped upon W.C. Fields’ portrayal of Micawber, but reviews at the time also discussed how much more enjoyable the first part of the film, that featuring Freddie as young David Copperfield, was in comparison to the latter half after David grows up to become Frank Lawton. I certainly agree.

We see the neophyte actor cling to his mother, played by Elizabeth Allan, when taken by Jessie Ralph’s Peggoty to her brother Dan’s seaside home where Freddie buzzes Lionel Barrymore with questions. Master David recoils at the treatment of Basil Rathbone’s Murdstone and finds his footing under the roof of Fields’ Micawber before really being allowed to enjoy boyhood under the auspicies of his Aunt, played by Edna May Oliver, and Lennox Pawle’s wacky Mr. Dick. Finally Copperfield is afforded a brief and awkward scene with Roland Young’s creepy Uriah Heep before growing into the much less charming Frank Lawton after a passage of years.

Andre Sennwald of the New York Times wrote that Copperfield’s “superb caricatures of blessed memory” were “led by a manly and heartbreaking David who is drawn to the life in the person of Master Freddie Bartholomew,” though like others Sennwald reserves much of his praise and the majority of article space for Fields.

Fields, by this time notorious for his distaste of working with children, by all accounts found Freddie Bartholomew more pleasing to work with than other child actors. Freddie himself, by then preferring to be called Fred, confirmed the amiable relationship in a 1962 AP interview where he said, “Some of my happiest memories are those of W.C. Fields entertaining with his juggling when we made David Copperfield.”

Freddie Bartholomew was rewarded with immediate stardom and a sugary part as Greta Garbo’s little Sergei in Anna Karenina (1935).

The part was small with Freddie not even showing up until nearly halfway through Anna Karenina, but he held his own with the great Garbo, often clinging to her cheek to cheek while serving the important purpose of being the only thing strong enough to keep Garbo under Basil Rathbone’s roof and out of Fredric March’s arms.

While Little Freddie fails to spoil Big Freddie’s good time with Garbo, he does lure his mother back for one final heartbreaking reunion which is one of the most memorable scenes of the movie. Freddie only interacts with Fredric March once in Anna Karenina but more than holds his own with Rathbone and, surprisingly, Garbo.

Basil Rathbone recounts difficulties with Freddie getting through a scene on Anna Karenina in his autobiography In and Out of Character. Hollywood’s newest child star and Rathbone, thus far Freddie’s own personal on-screen villain, actually got along very well and so director Clarence Brown left the problem to be sorted out by the older actor.

Rathbone told Freddie that the scene was a flop advising that “You are not listening to what I am telling you, about your mother’s going away for a long time. And if you are listening you are not conveying any feeling. You are just making a lot of noise and hamming it up.” To get the desired reaction out of Freddie, Rathbone told him to forget about the script: “Just imagine it’s me, your Uncle Basil, and I am breaking the news to you that Cissie is dead.”

Well, this imagined news about his beloved Aunt hit Freddie like a ton of bricks and you can see the results on screen in Anna Karenina.

With just these two MGM hits under his belt Freddie Bartholomew was given a pay bump from $100 per week to $1,250 placing him second only to Shirley Temple’s $2,500/week among child stars at that time. Promotional articles of the period claimed Freddie pocketed anywhere from a nickel to a dollar a week for himself, confident that his Aunt Cissie was saving the rest of his earnings for when he came of age.

With just these two MGM hits under his belt Freddie Bartholomew was given a pay bump from $100 per week to $1,250 placing him second only to Shirley Temple’s $2,500/week among child stars at that time. Promotional articles of the period claimed Freddie pocketed anywhere from a nickel to a dollar a week for himself, confident that his Aunt Cissie was saving the rest of his earnings for when he came of age.

Of Cissie, who was legally appointed Freddie Bartholomew’s guardian October 22, 1935 by the Los Angeles Country Superior Court, Freddie would say, “She’s my aunt and my uncle, my sister and my brother, my sweetheart and everything else–and she always will be too!”

Aunt Cissie also received $800 per month for the trouble. And yes, the same sweet boy audiences saw on the screen in David Copperfield and Anna Karenina was presented by the press with special stress always placed on his politeness and intelligence which was said to rival that of many Hollywood adults.

Freddie’s final release of 1935 was Professional Solider which hit theaters just before the New Year. Based on a Damon Runyon story, Professional Soldier starred Victor McLaglen, in his first release following his Academy Award winning performance in The Informer. In this one McLaglen is a soldier of fortune given the task of kidnapping Freddie, a young European monarch. The two were said to get along famously during the production of this film, McLaglen even gifting his young co-star a horse afterwards.

Bartholomew was on loan out to Twentieth Century-Fox for Professional Soldier. Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times enjoyed the film despite admitted deficiencies calling it “incongruous, it is loud, and, intermittently, it is funny.” The best part of Nugent’s review is it’s close where he writes that it has “the claim to fame in presenting the most amazing co-starring team in film history–Victor McLaglen and little Freddie Bartholomew.”

By the time Nugent had reached this line his review had taken on the overall fun tone of Professional Soldier and so I can imagine he made this statement with tongue in cheek. While Professional Soldier doesn’t have nearly the reach today that Freddie’s first two movies have, the film he was working on towards the end of 1935 certainly does: Little Lord Fauntleroy, also for Twentieth Century-Fox.

Little Lord Fauntleroy

Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times declared that “Master Bartholomew was a much better Lord Fauntleroy than he was a David Copperfield,” and while Nugent acknowledges that as a literary property Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Fauntleroy, “scarcely merits association with David Copperfield and Anna Karenina” he goes on to state that David O. Selznick has “transferred it to the screen with equal consideration and understanding.”

A big deal was made of the fact that Freddie’s Fauntleroy did not appear with the usual curls and fancy dress, instead Burnett’s literary property was more or less molded to the Freddie Bartholomew character formed over his two previous outings.

Unabashedly sentimental and marred by the intermittent interruption of Mickey Rooney working with one of his worst accents (a forced Brooklynese), Fauntleroy stands out not only because we are treated to the world of Freddie’s discovery as previously mentioned, but because we are also allowed to marvel at his pure goodness through the eyes of his elders.

Unabashedly sentimental and marred by the intermittent interruption of Mickey Rooney working with one of his worst accents (a forced Brooklynese), Fauntleroy stands out not only because we are treated to the world of Freddie’s discovery as previously mentioned, but because we are also allowed to marvel at his pure goodness through the eyes of his elders.

This group included characters played by Jessie Ralph, Guy Kibbee, Henry Stephenson, and most importantly, C. Aubrey Smith, who plays Freddie’s grandfather, the Earl of Dorincourt. Each of their characters, hardened by life in one way or another even if it’s just the simple passing of time, respond throughout Fauntleroy with their own moments of wonder in response to the young Faulteroy’s absolute innocence.

Time and again the elders are astounded by the boy’s charity and his simple ignorance caused by not expecting anything but the best out of others.

Fauntleroy begins in my favorite Freddie fashion where his cultured young Ceddie sticks out like a sore thumb amongst the rest of the rotten city. If you thought Freddie a little sugary with Garbo in Anna Karenina, well then you may have a tough time swallowing his Ceddie’s relationship with his mother, Dearest, played by Dolores Costello Barrymore in Fauntleroy.

When a gang of toughs harass Ceddie for a ride on his new bicycle, he winds up getting popped in the eye by one of them. His pal, the bootblack Dick (Rooney), rushes to his aid and bodies fly everywhere. Rooney and Bartholomew are well on their way to handling the entire gang of toughs before the neighborhood policeman sends the other boys scattering. That policeman is a Ceddie fan, like everyone else in the neighborhood who has had the pleasure of this pure boy’s acquaintance.

Before heading home to Dearest, Ceddie stops by Mr. Hobbs’ (Kibbee) general store where the two ruminate over the evils of the British Lords. In Ceddie’s next visit to Mr. Hobbs he is much embarrassed to admit he’s just found out he’s been made a Lord himself and will soon be departing to England to live whatever life it is that a Lord lives. He promises not to forget Mr. Hobbs or Dick the bootblack.

In heading to England Ceddie is kept ignorant of the fact that his grandfather, whom he believes is a kindly and generous old Earl, is in reality a mean-spirited old miser who will have nothing to do with Ceddie’s mother. Dearest does make the trip but is placed in a home separate from Ceddie and the Earl. She refuses to tell Ceddie the real reason for their separation out of fear of alienating the boy from his grandfather. C. Aubrey Smith as the Earl is as cranky as you could imagine, blowing up at servants and terrorizing the townsfolk, but even the crusty old Earl is taken in by Ceddie’s charm and softens as a relationship grows with the boy.

Perhaps more than any other Freddie Bartholomew film we are meant to observe his character as much as we walk in his shoes and frankly the kid is quite likable as a thoughtful, overly polite young man, full of questions and curious as to what his own fate shall mean.

Little Lord Fauntleroy would be Freddie Bartholomew’s fourth consecutive hit and unlike Copperfield, in which he appeared before audiences as an unknown quantity who disappeared halfway through the film, or Anna Karenina, where he tallies maybe ten minutes total screen time, Fauntleroy is Freddie’s showcase. Surrounded by wonderful character actors, including a few noted scene stealers, Freddie holds his own and there can be no doubt the project is his. He’s a star.

After the success of Fauntleroy Freddie was making $1,500 per week. This number was high enough to start bringing other Bartholomews across the Atlantic for a claim of their share.

Legal Troubles

Mother Lillian Mae came first, arriving in New York in early April 1936. Lillian Mae, described by United Press as “a quiet, black-haired woman about 35 years old,” told the world that Freddie and Cissie had cut off all communications back home. She claimed that “We have not had a letter from Freddie or his aunt since they left England. We have written and cabled a number of times without reply. We have tried to telephone Hollywood, but the call was refused. So at last I decided to make the trip. I would have done so before but lack of funds prevented it.”

Mrs. Bartholomew crossed the Atlantic third class with her husband’s blessing. Cecil, described by United Press as a “war cripple” told Lillian Mae to bring Freddie back, “but not to injure his future.” Whatever that may mean.

Mrs. Bartholomew crossed the Atlantic third class with her husband’s blessing. Cecil, described by United Press as a “war cripple” told Lillian Mae to bring Freddie back, “but not to injure his future.” Whatever that may mean.

Over the years the older generation of Bartholomews put together a press packet as thick as Freddie’s own and it was fantastic right from the start with headlines trumpeting that Lillian Mae had gone missing sometime after her New York arrival.

The story of Lillian Mae’s disappearance made headlines on both sides of the Atlantic when a frantic Cecil told the press that he believed his wife had been kidnapped as part of a plot to keep them from regaining Freddie. At Penn Station in New York a westbound train was delayed so detectives could search for Lillian Mae, but they came up empty.

Upon arrival she was supposed to meet attorney Phillip A. Levy in New York, but Levy had no word from her and reported her disappearance to the Missing Persons Bureau. Back in England Cecil received a wire in which Lilian claimed to have arrived safely and to be traveling igcognito; this sent Cecil into a greater panic as he said his wife would have no idea what the term incognito would even mean.

It turns out that Lillian had met a Joseph G. Hobbs, London barrister, on the ship over to the States and it appears that Hobbs had convinced her to book a flight to Washington to bring her case directly to the government’s attention. Inclement weather caused Lillian to cancel the Washington flight.

Two days of kidnapping headlines came to an end when Lillian Mae arrived in California where she checked in with the British consulate and a local attorney who branded the nationwide search for her as publicity.

Meanwhile Freddie was kept ignorant of all this with Millicent’s attorney stating that the boy star would not be told “unless it was absolutely necessary.”

Upon settling in Los Angeles and taking some time in seclusion Lillian would file petition with the courts attempting to reverse the previous ruling which had appointed Millicent as Freddie’s legal guardian. Cecil dropped a bomb on the case from overseas when he sent a wire stating “The deponent has complete confidence in Millicent Bartholomew, and feels that the interests of the minor will be best served by leaving his control in the said Millicent Bartholomew’s hands, subject to the co-operation with the deponent.”

In other words Cecil had withdrawn his support from his wife and thrown it in favor of his sister, Freddie’s Aunt Cissie.

Lillian claimed that Cecil had made an agreement with Millicent whereby one third of Freddie’s earnings would go to them, a third to Millicent, and a third into a trust fund for Freddie.

The first battle came to a seemingly peaceful end before April 1936 was out when it was arranged for Lillian to meet with her son, Freddie, for the first time since he had departed England. Freddie’s grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Robert Bartholomew, who made the trip over to give Millicent backing over Lilian Mae, would also be present at that meeting.

Judging by their mention in later reporting this elder generation of Bartholomews apparently stayed on in America in a home financed by their grandson.

The Devil Is a Sissy

Back at work Freddie’s home studio, MGM, would give him top bill in a fun project teaming him with their two other top child stars, Mickey Rooney and Jackie Cooper. Rooney, who had just appeared with Freddie in Fauntleroy, was clearly on the rise, while Cooper, who had grown a little large for his age had already left his most famous days behind him.

The film, The Devil Is a Sissy, was an exciting romp which saw Freddie leave his high class mother’s custody to spend the summer on the skids with his bohemian father, played by Ian Hunter. Freddie, a kind-hearted little dandy, does his best to win the approval of a gang of kids led by Buck Murphy (Cooper) and Gig Stevens (Rooney), a boy whose criminal father was just electrocuted in the electric chair.

Spreading the spectrum from comedy to drama with a touch of romance, a musical number thrown in out of the blue after Peggy Conklin turns a cartwheel that lands her at her piano bench, and a climax hinging on a brief gangster plot, The Devil is a Sissy is all over the place but remains great fun at a break neck pace.

Freddie is at his best here trying to overcome his high fallutin’ accent and the upper class ways that come packaged with it to get down and dirty with the other boys, a group also including Bugs–who eats bugs–and Six Toes–who has six toes, “By Jove, I say now, this is something!”

Following Sissy Freddie was again loaned out to Twentieth Century-Fox to play young Jonathan Blake in the first quarter or so of Lloyd’s of London, a historical drama which would see Freddie grow up to become … Tyrone Power!

Perhaps the most amazing thing about Lloyds is Power, in an early role, more of less stepping right into the Blake personality established earlier in the movie by Freddie. Freddie’s Blake was his most rough and tumble character to date. For instance, he was considered the bad influence over his boyhood chum, who incidentally grows up to become Lord Nelson.

As in Copperfield we see Freddie take a long hike that leaves him in bedraggled clothing, though in Lloyd’s this was a voluntary journey which would wind up taking him out of poverty and placing him in Lloyd’s coffee house. There his entrepreneurial spirit is immediately stirred by the excitement of business.

After Lloyd’s Freddie returned to MGM to appear in what would become his most important role, little Harvey in Captains Courageous which would win Spencer Tracy his first of two back to back Academy Awards and receive three other Oscar nominations as well.

Captains Courageous

Kipling’s original Harvey was 19 in the story, but in order to cast Freddie the character was changed to a 12 year old. Captains Courageous gave Freddie his first opportunity at playing a spoiled brat. Harvey gains his comeuppance at the hands of Tracy’s proud Manuel, a second generation fisherman who creates songs out of thin air and reels his fishing line in and out by hand.

The son of a super-wealthy Melvyn Douglas, not a bad guy himself, Freddie’s Harvey tortures his schoolmates with his inherited power but steps too far and eventually finds himself expelled. Harvey accompanies his father on a cruise which is supposed to offer them a chance at bonding with the hope that Harvey somehow manages to absorb his father’s better qualities. Harvey continues his power trip on board the ship where he forces a soda stand to open and insists upon drinking several milkshakes in order to impress a couple of kids who he has met on board. How else is a 12 year old to prove their power?

Sick as a dog after accomplishing his feat, Harvey tumbles overboard into the sea where, unconscious, he is picked up by Manuel who dubs him his “Little Fish.”

Harvey tries to assert his power on board the schooner, We’re Here, but after humoring him for a few moments the Captain, Disko Troop (Lionel Barrymore), gives it to him straight: he’s trapped on board, the livelihoods of too many men are at stake to turn back based on what is probably a made up story about his father, a man supposedly rich enough to own the big ship Harvey fell from. If Harvey wants to eat he had better learn how to work. Disko provides an exclamation point in the form of a backhand across the obnoxious Harvey’s face, which judging from Bartholomew’s expert expression of hurt and shock marks the first time in his life that little Harvey didn’t get his way.

Harvey sulks at first but eventually accepts his fate through his bonding with Manuel which goes through it’s ups and downs but winds up cementing itself as what will undoubtedly be the most important relationship of Harvey’s entire life.

Nugent of the Times admitted “Young Master Bartholomew, who, frankly, has never been one of this corner’s favorites, plays Harvey faultlessly,” and draws a comparison to one of Freddie’s previous co-stars calling his Harvey, “as reptilian a lad as a miniature Basil Rathbone might have managed,” before softening him through his relationship with Tracy’s Manuel.

Upon winning the Academy Award for Best Actor Spencer Tracy said, “It was really Freddie Bartholomew who should have won that trophy. I’m not trying to be modest or heroic but actually my ‘Manuel’ wouldn’t have been so much without him. There is one marvelous kid. He can give lessons in acting to anybody in this town.”

Captains Courageous still holds up and remains the classic in which the casual film fan is most likely to encounter Freddie Bartholomew.

Money Troubles

It was while Captains Courageous was in production that a bodyguard would have to go to work for Freddie Bartholomew after Aunt Cissie received a kidnapping note demanding $50,000 and further threatening “If the police are told it will be just too bad for Freddie.” The threat came from an ex-convict named David Harris Weazend who also sent out a similar note to Jane Withers. “I was hungry and I figured it was a way to make easy money,” Weazend said. He’d be sentenced to 25 years in prison for his appalling gamble.

Little could the would-be kidnapper guess that Freddie needed more money himself.

With four years remaining on his traditional seven year contract at MGM Aunt Cissie declared that Freddie was broke and needed a raise.

Bartholomew’s demands were well-timed, just a month and a half after the release of the hit Captains Courageous, but the battle would keep Freddie Bartholomew off the screen for nearly a year and it is no surprise to see that upon his return he would never again act in films the quality of his first few major screen appearances. The career span of a child star isn’t long so I can understand the Bartholomews pressing for as much as they could get while Freddie was a hot property. But I have no doubt that the studio struck back with lesser projects, and even those Freddie would soon grow out of.

The contract battle would play out in the courts and the newspapers with Cissie taking the stance that they were going to break contract with MGM for greener pastures because of the shady circumstances under which Freddie was originally signed by the studio for David Copperfield.

Cissie said that she was told in England by a Mrs. Bollio, an agent for MGM, that “it will be necessary for him to go to Hollywood to make the picture; to take him there is illegal and in violation of the child labour laws of England; we must therefore not discuss the matter with anyone.”

Cissie went on to say that since they were too broke to afford the trip overseas on their own MGM paid for everything leaving her under pressure to sign: “I didn’t want to sign, but I didn’t know what else to do … I was in a strange country, without funds except those MGM provided … I finally signed Freddie’s contract, but it was against my will.”

The courts sided with the studio and blocked Freddie from working for anyone other than MGM while on his suspension which had begun July 15.

While admitting Bartholomew was a mega-star who made them a ton of money it looked good for MGM that they had given him voluntary pay raises after his early successes. The battle was settled in mid-October when MGM raised his salary to $2,500 per week.

In the meantime Freddie had lost the lead in Thoroughbreds Don’t Cry to New Zealand’s 14-year-old Ronald Sinclair who managed a fine Freddie Bartholomew impersonation opposite Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland.

Perhaps the most humorous story to come in the wake of Freddie’s raise was the report of “More Bartholomews” from the October 21 edition of The Daily Mirror in which Freddie’s dad, Cecil, announced he’d be bringing his daughters Eileen and Hilda to Hollywood to set them to work. I don’t see any evidence of him having followed up on this dollar induced dream.

Freddie’s legal woes continued through the close of 1937 when a Superior Court Judge ruled against Cecil and Lillian Mae’s latest attempts to wrest custody from Cissie.

Freddie himself testified, “I would not care to go to my parents, for, you see, they are practically perfect strangers to me. I am very happy with my aunt. I love her very much. She is like a mother to me. In. fact, she has been my mother since I was three years old.”

Cissie meanwhile was trying to take away control of Freddie’s financial affairs from a trust company who had been granted guardianship over his earnings. On another front his former agents at The Selznick Company filed a breach of contract suit attempting to recover $39,500 in fees from a broken contract. The Selznick Company was headed by Myron Selznick, brother of producer David O. Selznick who had made himself into one of Hollywood’s top agents. Freddie’s filmography is notably absent of any Selznick productions following Little Lord Fauntleroy, so this likely turned ugly.

Soon enough all of Freddie Bartholomew’s financial troubles would be laid out in black and white for public consumption.

Freddie Bartholomew was finally back to work in early 1938, initially on loan-out once more to Twentieth Century-Fox for their production of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped, and then back on the home lot paired again with Mickey Rooney for Lord Jeff. After that, Freddie found himself opposite Judy Garland for the only time in his career in the disappointing Listen, Darling

, best remembered for Garland’s performing “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart,” but little else. It’s a tough watch for the Freddie fan.

Early in 1938 Freddie Bartholomew petitioned the courts for permission to discontinue payments of 20% of his salary to his father, an amount awarded in one of the previous Bartholomew court sessions. In doing so Freddie’s assets and debts were disclosed to the public record with the latter far outweighing the former.

With just $1,800 in his bank account Freddie had debts amounting to $56,800. And somehow the itemized tally totals far more that that. He owed $67,000 in income tax, $15,000 in attorney’s fees, $5,000 in agent’s fees, $44,300 in past agent’s fees thanks largely to The Selznick Company suit named earlier, plus $3,800 in living expenses.

The courts allowed payments to his parents and attorneys to be set aside and also made Freddie a financial ward of the Superior Court. This removed responsibility from the bank that his Aunt had previously battled for custodianship. That bank had depleted his savings from $30,000 to $400.

Now with his finances in the court’s control even Cissie couldn’t spend a dime of Freddie’s money without court approval. The result of these actions led to Freddie finally banking some money in 1939 which was made public record in January 1940. At that time Cissie reported to the courts that his savings account had swelled to $75,000, his checking account to $14,000, and that he owned $37,909 worth of U.S. savings bonds, increasing his estate overall by $94,324 since January 1 of that previous year.

1939 wasn’t entirely smooth sailing for Freddie’s finances however as in June of that year his parents sued him for $1 million naming Cissie in the case and claiming a conspiracy to cost them Freddie’s affection and companionship (value: $200,000), lost earnings ($300,000), and general punitive damages of half a million. A settlement was reached which tided things over until Cecil and Lillian Mae decided it wasn’t enough. They managed to get the high court to reopen the case in 1942 after Freddie had turned 18.

1939 wasn’t entirely smooth sailing for Freddie’s finances however as in June of that year his parents sued him for $1 million naming Cissie in the case and claiming a conspiracy to cost them Freddie’s affection and companionship (value: $200,000), lost earnings ($300,000), and general punitive damages of half a million. A settlement was reached which tided things over until Cecil and Lillian Mae decided it wasn’t enough. They managed to get the high court to reopen the case in 1942 after Freddie had turned 18.

On the screen Freddie was still credited with fine acting though he had lost appeal with audiences after shooting up to nearly 6 feet tall–Lord Fauntleroy was not so little anymore.

In 1939 he appeared in a pair of films on loan out to Universal, Spirit of Culver and Two Bright Boys. With his $100,000 MGM contract set to expire in October 1939, Freddie arrived at the studio one day in July to find his dressing room locked and his belongings packed up in a storeroom. “I don’t mind,” Freddie told reporter Sheilah Graham, “But it’s the wear and tear on poor Aunt Cis that gets me down.”

But his name still had value and he soon found work on another literary classic in Swiss Family Robinson with Thomas Mitchell and Edna Best heading the family Robinson. Freddie and Terry Kilburn, child star who’s face you’ll immediately recognize from Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), garnered the most publicity from the film with the press even trying to set up a rivalry based upon Kilburn out Bartholomewing Freddie.

Swiss Family Robinson was the first of only three films produced by The Play’s the Thing Productions, Inc. Freddie would also appear in The Play’s the Thing’s second film, Tom Brown’s School Days, but he wouldn’t be a part of their final effort, Little Men (1940).

Jimmy Lydon actually had the lead role in Tom Brown’s School Days, but Freddie was still one of the top three billed stars in the film along with Sir Cedric Hardwicke, who played the headmaster of Rugby, Dr. Thomas Arnold. The movie opens with Freddie’s character, East, apologizing to Lydon’s Tom Brown over a memorial to the since deceased Dr. Arnold. Then we’re taken back in time and treated to the entire rise and fall of their friendship with Lydon’s Tom Brown of the title the focus of the movie.

Freddie played the cocksure young man who welcomed Brown to the new school at first seeming only to have ideas on Brown’s pocketbook but soon earning a respect for the way Tom carried himself.

While the boys hold an uprising against bullying they must do so without tattling on their tormentors because the greatest crime of the school is telling tales out of turn. Tom Brown eventually discovers that doing so leads to total ostracism. Freddie’s East has the unenviable task of cutting himself off from Brown and circumstances cause him to hold out longer than any of the other boys in severing what was once a close friendship.

While Freddie’s East does come off as a little stubborn he’s still a likable chap and on the whole a much more realistic character than Brown himself, who can be, like some of Freddie’s own earlier characters, a little too sugary.

The film was a poverty row knock-off of the classic Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), but with it’s own literary legacy and a fine cast that also included Josephine Hutchinson, Polly Moran and Gale Storm in her film debut. It’s easily enough seen today as a public domain offering, but unfortunately the quality of the available prints is poor.

Freddie’s career slowed down after being cast off by MGM. He only appeared in one film in each 1941 and 1942, Naval Academy and Cadets on Parade both for Columbia.

Finally MGM welcomed him back for 1942’s A Yank at Eton where in a reversal of previous fortune he offered support to the star, Mickey Rooney.

18 year old Freddie, tall and gangly, must have still retained some of his old appeal as Columbia, where he had made the two films prior to Yank, signed him to a contract. First reported by Louella Parsons in April 1942 as a two picture deal with terms undisclosed, in July the Associated Press reported that Superior Court had approved what was a one-year contract with Columbia at $2,250 per week.

Freddie appeared in just one movie under the Columbia deal, Junior Army, in which he headed a cast reuniting him with Tom Brown co-star Billy Halop along with Halop’s fellow Dead End Kid chums Huntz Hall and Bobby Jordan.

Showing us another side of Freddie as he recalled him in a 1974 interview Halop said, “Freddie Bartholomew used to play sissy types in pictures, but he wasn’t like that at all. We used to cruise up and down in a Cadillac and pick up broads.”

War

Just prior to the one year anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor 18-year-old Freddie Bartholomew enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. “America gave me an opportunity and I am glad for a chance to serve her,” he said. Time Magazine pointed out that after taking out his first citizenship papers in March 1942, Freddie would automatically be awarded U.S. citizenship upon completion of three months of service.

Freddie was sworn in to the Army January 13, 1943 and served as a student-mechanic at the airfield in Amarillo, Texas. He was discharged a year later, January 12, 1944 due to a back injury. This injury is often reported as having taken place during his service time but I found it referenced as having been suffered in 1939 at the hands of someone pulling a chair out from under him as a practical joke. Perhaps the injury was reaggravated during service.

At the time of his discharge Freddie said, “I’m going to try to get well and get back in the Army. If I can’t make it I may go back to pictures.”

Back in Hollywood, Freddie was no longer a child star and appears to have had a hard time finding work appearing only in the Roth-Greene-Rouse production The Town Went Wild in 1944. This one reunited him with Tom Brown’s School Days co-star Jimmy Lydon. The Town Went Wild would be Freddie’s last film appearance for seven years and unfortunately that later effort would not be the beginning of a comeback, but a pretty concrete good-bye.

1944 also saw Freddie involved in an auto accident which must have weighed on him. Freddie was driving his midget automobile between 25 and 30 miles per hour on November 4 when he crossed a West Los Angeles intersection and collided with another midget auto driven by Betty Lee Cast, 22. “A sudden blur of lights,” was all that Freddie could remember according to his account before the Municipal Judge in January 1945.

Riding with Freddie was his grandfather, Frederick Bartholomew, 85. Neither they nor Miss Case were injured. However, Miss Case’s two passengers were Mary and Katherine Brown, daughters of Hollywood star Joe E. Brown. Mary was unconscious for 16 days after the crash with injuries including a triple skull fracture, a broken leg and internal injuries. Katherine was not badly hurt. Mary Brown was still unable to walk under her own power as many as 11 months later when she appeared in the papers walking with the aid of steel braces.

After Freddie testified all charges were dismissed against Miss Case.

Despite his barren postwar filmography Freddie was somehow considered for a comeback part in 1945’s Adventure which starred Greer Garson with Clark Gable, who was making his return performance after serving in World War II. Adventure was most definitely an A level production making Freddie’s consideration all the more interesting.

There was also talk of Freddie going to England to appear in Gabriel Pascal’s L’Aiglon, but the project never came to be.

Postwar

The fact that Freddie Bartholomew was off the screen didn’t mean that he was without work altogether. Or for that matter without representation. On April 25 of 1946 22-year-old Freddie married his press agent, the former Maely Daniele, whom he had met during a Little Theater production of “Candida” on the West Coast.

Freddie Bartholomew with first wife, Maely Daniele

Maely was 6 years older than Freddie and already had two marriages behind her. This was much to the consternation of Aunt Cissy who was quoted in papers as saying “Isn’t it dreadful? This is the worst thing that has happened in the 12 years we’ve been in Hollywood.” Cissy continued, “He told me she had been married four times (actually Freddie was Maely’s third husband, though there’d be two more after him). It’s all so sordid.”

The papers also asked grandfather Frederick what he thought and the old-timer plainly told them, “I’d like to wring his neck.” Maely’s divorce had gone through just the month before her marriage to Freddie Bartholomew.

Aunt Cissy had previously put a stop to Freddie and Maely’s first attempt at getting married earlier that April and it appears as though his going through with the surprise elopement a few weeks later drove a wedge between them that soon drove Millicent Bartholomew back to England. She remained overseas until her death in 1970.

Whether Freddie and his Aunt ever truly reconciled I do not know, but he did honor her legacy by naming his first daughter Kathleen Millicent in 1956 and spoke fondly of her in the interviews I’ve seen after his marriage to Maely.Freddie didn’t fare well in The Billboard reviewing his Vaudeville act as it stopped at Loew’s State Theater in New York, December 1946. The Billboard gave Freddie and A for effort but said that he failed to get his act over with the audience. “He gabs a little, chants a little, tells dialect stories, does a whiff of Shakespeare and closes with mimicry, but nothing really clicks solid.”

That same month Freddie appeared as himself in Herald Pictures Sepia Cinderella (1947), a musical with an otherwise all-black cast that was released to segregated theaters.

By New Year’s 1948 an Amsterdam, NY paper seemed pretty excited by its headline of “Noted Actor to Appear in City At Junior High.” Yes, our man Freddie is the noted actor and he had the lead in a performance of “The Hasty Heart” being put on at the Junior High by The Amsterdam Business and Professional Women’s Club.

Freddie continued the push towards a comeback on the American vaudeville circuit before departing for a gig at the Celebrity Club in Australia in November 1948. His wife, Maely, did not accompany him overseas.Freddie received a salary of approximately $2,093 with round-trip airfare and hotels all taken care of by the Club. Jerry Rosen, who booked the tour from the U.S., planned on acts staying in Australia for months, touring theaters and appearing on radio after finishing up at the Celebrity Club.

Most of Freddie’s biographical information credits him with owning a club during his time in Australia, but there is no record of that.

During this tour Freddie made numerous appearances in Australian newspapers. His act was said to consist of singing plus some patter with audiences all accompanied by his playing on the piano. Basically the same act that The Billboard had previously panned. Australian papers were more polite.

While the more in-depth coverage of Freddie’s Australian engagements always made a point to talk about how happily married he was they also pointed out that Maely remained home in America during Freddie’s stay in Australia.

Maely was an interesting figure who I’ve seen listed as being born in places as varied as Paris, Russia and Czechoslovakia. During the time of her marriage to Freddie, Maely would become a lifelong friend and by some reports business manager of the legendary Billie Holliday. It appears that through Holliday she met her next husband, William Dufty, ghostwriter of Holliday’s Lady Sings the Blues, and himself a future husband of Gloria Swanson.

Maely’s involvement in Civil Rights activities is always mentioned in her later clippings, usually planting her in Harlem rallying for one cause or another. She married once more and died Maely Dufty Lewis in 1984.

A New Career

After returning from Australia Freddie Bartholomew settled down with Maely in New York where he became involved with television.

While he has a handful of early TV credits on the IMDb, acting wouldn’t be Freddie’s primary occupation. Instead he had become the WPIX TV director in 1949, a profession which would lead to some of my favorite Freddie Bartholomew stories courtesy of Guy LeBow who gives over an entire chapter to the story of Freddie’s life at this time in his entertainingly titled Watch Your Cleavage, Check Your Zipper!

LeBow writes that Freddie “was immediately and eagerly accepted by the Channel 11 staff. And loved by most everyone. As he settled in among his new colleagues, his own defenses slowly gave way and he returned love and loyalty in heaping amounts, to say nothing of laughter.”

It seems Freddie had grown into a practical joker and LeBow recounts one of his more daring exploits:

One late evening while Freddie was in charge of station operations, a staff film projectionist privately showed him a five-minute clip of explicit sexual action. What led Freddie to his next move we innocent but interested bystanders will never know. At 12:30 a.m. the station signed off and played the National Anthem. At 12:34 a.m. Freddie had the fornication film put on the air. And so appeared television’s first pornographic show. Several viewers wrote enthusiastic letters. But until this day, Channel 11 executives think it never happened (250).

LeBow tells another story of a time WPIX was going to air a show investigating local Communist activities. This was right in the middle of the Red Scare and the heights of McCarthyism. Freddie somehow got his hands on an official Communist Party membership card and flashed it to one of their co-workers on the side. Freddie scared the kid to death when he told him, “I’m a charter member and I’ve been told to contact you because you’re the new recruit. Welcome.” He strung the kid along for a bit before letting him off the hook.

LeBow wrote that Freddie wouldn’t discuss his Hollywood career at all and that he was shocked to see the hard times his one time favorite child star had fallen on. He describes Bartholomew as “experiencing hell. His fortune has been spirited away. He has outgrown his screen image. His good looks have been disarrayed by nature and problems. A bad marriage. And he is broke” (248).

Freddie earned his own chapter in LeBow’s book because of the impact he had on the author’s own life: “This decent person who lived with grace and dignity among the famous and infamous was a lesson in human strength and humanness at its best.”

In August 1950 The Billboard announced that Freddie had signed a contract with Admiral Records, not to record the live routine he had been performing the past few years, but to record fairy tales for a series of children’s recordings.

But LeBow’s coverage was really the last up close and personal look I was able to find of Freddie Bartholomew. Certainly we wouldn’t learn much from Freddie’s final feature film, St. Benny the Dip, released in 1951.

St. Benny the Dip is pretty good for a poverty row production and I would imagine especially enjoyable for fans of Lionel Stander or Roland Young, but it is a very depressing screen finale for Freddie Bartholomew fans.

Fifth billed in the Edgar G. Ulmer directed tale of redemption behind Dick Haymes, Nina Foch and the aforementioned Stander and Young, Freddie, as Reverend Wilbur, is the more or less invisible sidekick to the elder Reverend Miles, played by Dick Gordon.

Armed with dialogue consisting of oohs, ahhs and various other exclamations, Freddie’s Wilbur follows Miles around like a puppy dog as the elder Reverend oversees the reformation of Haymes, Young and Stander, three petty crooks who soak in the atmosphere of the religious garb they stole from the Reverend’s church while escaping the police.

Released by United Artists I can only imagine St. Benny the Dip was Freddie’s last gasp at resurrecting his film career simply because Danziger Productions, who made the film, was local to him and the filming was done in New York. Or perhaps he owed someone a favor, in either case the film certainly didn’t do him any good turns.

Freddie popped up on the air again for WPIX in New York as emcee of Fashion Review, which was called “pretty bad” by journalist John Lester . Lester did find novelty in Freddie occasionally modeling some of his own items from time to time, “masculine items, of course.” A few months later in May 1952 Freddie popped up in the same TV column as Lester introduced viewers to PIX’s “Melody Scrapbook,” a music clip program directed by Freddie that aired at sporadic times following day games of the New York baseball Giants.

After his divorce from Maely and while he was still working at the television station, Freddie would meet his second wife, Aileen Paul. At that time Paul was a television personality herself who Freddie directed in her WPIX program “New York Cooks.”

Freddie and Aileen were married in Yonkers Unitarian Church, December 12, 1953 and would remain married for approximately 23 years. Daughter Kathleen Millicent was born in March 1956 and son, Frederick, Jr. came two years later. While Freddie would receive a rash of publicity in the early 1960’s for his success as an advertising executive with Benton & Bowles Agency, for whom he went to work in 1952, most of the later press would go to Aileen who authored a series of books teaching children how to cook.

While his film career was firmly behind him, Freddie did continue to associate with the celebrity set. He’s reported to have been at a Hollywood party at Chuck Conners’ home in 1962 while in town on business. The Bartholomews settled in Leonia, New Jersey where many other celebrities also called home. Neighbors included young Alan Alda, writer Robert Ludlum, comedian Buddy Hackett, and singers Pat Boone and Sammy Davis, Jr.

Freddie’s job would also keep him in touch with celebrity, but from behind the camera where for Benton & Bowles he produced television shows such as “The Andy Griffith Show” and “Many Happy Returns” for B&B’s General Foods account.

The former Little Lord Fauntleroy was living the life of Mad Men in his 40’s!

America was astounded to see this well circulated shot of Freddie Bartholomew, then and now, in 1964 newspapers

Freddie and Aileen separated sometime in late 1976, possibly early 1977, with the couple still together as late as September 30, 1976. Santa Fe, New Mexico newspapers announced Aileen’s moving permanently to the area by February 1977. By September 1977 Aileen is now referred to in the press as Aileen Paul Phillips, having remarried. She continued to be a very active writer and remained Mrs. Steven Phillips until her death in 1997 just past her eightieth birthday.

Freddie Bartholomew continued working and often appeared in the Soap Opera notes in the early 1980’s when he was executive producer of soaps such as As the World Turns and Search for Tomorrow.

The final reference I can find to Freddie’s career came in 1983, but from that time until the end of his life in 1992 it is a bit of a mystery.

Just prior to his death Freddie finally sat down to discuss his career in the still popular 1992 documentary MGM: When the Lion Roars. Of old MGM boss Louis B. Mayer Freddie said, “He loved us so much he would do anything for us except, of course, pay us what we were worth.” Special attention is called to Freddie’s contributions in many of the reviews which appeared when the special first aired. By the time it aired Freddie was gone.

According the his New York Times obituary he married a third time to a woman named Elizabeth who survived him. I wasn’t able to track down Elizabeth’s maiden name, nor any reference to her at any time except in the Freddie Bartholomew obituaries.

Freddie Bartholomew died of emphysema, January 23, 1992 in Sarasota, Florida, where I assume he relocated upon his retirement.

One of the greatest child actors in the history of cinema, Freddie Bartholomew will always be remembered as Little Lord Fauntleroy and David Copperfield and we can only hope more of his films return to print sometime in the future (especially a decent copy of Swiss Family Robinson!).

Blessed with one of the greatest speaking voices the screen has ever seen, Freddie suffered through numerous legal battles with his family throughout the peak of his career and possibly wasted the opportunity of carving out an even greater screen legacy through money battles with M.G.M. that cost him a prime chunk of his film career during his youthful peak.

Freddie’s career was already headed south when he enlisted at age 18 and saw World War II cause another interruption to whatever momentum he may have had on screen at that time. Who knows, perhaps the press covering Freddie’s service time made everyone realize that yes, he really was all grown up.

Sources

Books:

- Behlmer, Rudy, ed. Memo from David O. Selznick

. New York: The Modern Library, 2000.

-

Hoerle, Helen. The Story of Freddie Bartholomew

. Akron: The Saalfield Publishing Co., 1935.

-

LeBow, Guy. Watch Your Cleavage, Check Your Zipper!

. New York: SPI Books, 1994.

-

Rathbone, Basil. In and Out of Character

. 5th ed. New York: Limelight Editions, 2007. 94-95.

-

Spicer, Christopher J. Clark Gable: Biography, Filmography, Bibliography

. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002. 226.

-

Zelizer, Viviana A. Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children

. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Magazines:

- Lardner, Jr., Ring W. “Will Hollywood Spoil Freddie Bartholomew?” Liberty. 11 Apr 1936.

- York, Cal. “Cal York’s Gossip of Hollywood.” Photoplay. Feb 1936.

Newspapers:

- “Actor.” The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 Nov 1948: 3.

- “Actor Has Turned Soap Producer.” The Baytown Sun. 6 Mar 1983.

- Anderson, Nancy. “Billy Halop Says There’s No Dead End.” The Gastonia Gazette. 1 Sep 1974: 40.

- “Agency Sues Freddie Bartholomew.” The Courier-Mail. 16 Nov 1937: 19.

- Baker, Ainslie. “Film Cry-Baby Now Amiable Man of the World.” The Australian Women’s Weekly. 11 Dec 1948: 24.

- Brownstone, Cecily. Tribune-Star. 22 Nov 1970: 43.

- “Celebrity Questions.” Winnipeg Free Press. 9 Jan 1982.

- “Child Film Stars. Kidnapping Threats. Ex-Convict Surrenders.” The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 Jan 1937: 10.

- “Child Star, Wanted by Mother and Aunt, Likes Dickens–And Sometimes Raises It.” The Galveston Daily News. 2 May 1936: 11.

- “Death of Italia Conti, Trainer of Stars.” The Advertiser. 11 Feb 1946: 7.

- “Film Star’s Daughters Hurt in Crash.” The Mercury. 7 Nov 1944: 5.

- “Freddie.” The Daily Mirror. 20 Feb 1976.

- “Fred Bartholomew Enlists.” The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 Dec 1942: 8.

- “Freddie Bartholomew. Boy Screen Star. Father’s New Attitude.” Cairns Post. 25 Apr 1936: 11.

- “Freddie Bartholomew Can’t Live Aunt Says on 225 A Week.” The Daily Gleaner. 16 Aug 1937: 19.

- “Freddie Bartholomew Gets Ready for Comeback at 25.” The Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner. 25 Jun 1948: 7B.

- “Freddie Bartholomew, Mother to Meet Sunday.” The Salt Lake Tribune. 26 Apr 1936: 10A.

- “Freddie Bartholomew Runnerup as ‘Most Valuable’ Film Child.” The Racine Journal-Times Sunday Bulletin. 27 Oct 1935: 6.

- “Freddie Bartholomew. Question of Custody. Father Supports Aunt.” The Mercury. 24 Apr 1936: 9.

- “Freddie Bartholomew’s Financial Affairs.” The Advertiser. 14 feb 1938: 21.

- “Freddie Bartholomew Spurns Parents for Aunt.” The Daily Messenger. 2 Nov 1937.

- “Freddie Bartholomew Tells of Injury to Joe E. Brown Girls. Los Angeles Times. 10 Jan 1945: A1.

- “Freddie Bartholomew To Marry TV Star.” Newport Daily News. 12 Dec 1953.

- “Freddie Bartholomew Wishes Public Would Forget Childhood.” Portland Press Herald. 31 Mar 1950.

- “Freddie Faces Aunt Cissie’s Ire.” San Antonio Light. 26 Apr 1946: 2-D.

- “Freddie’s In Town: Brings No Tears Now.” The Courier-Mail. 28 Dec 1948.

- “Freddy Bartholomew an Ad Executive Now.” Press-Telegram. 7 Nov 1964: B-12.

- “Funeral Services and Memorials: Aileen Paul Phillips.” Santa Fe New Mexican. 3 Aug 1997.

- Graham, Sheilah. “Say Metro Will Drop Freddie Bartholomew in October.” The Calgary Herald. 21 Jul 1939: 5.

- Harrison, Paul. “Paul Harrison in Hollywood.” Edwardsville Intelligencer. 4 May 1938: 5.

- Heffernan, Harold. “Spencer Tracy Grateful to Freddie Bartholomew.” The Milwaukee Journal. 25 Mar 1938: 1.

- Honan, William H. “Freddie Bartholomew Is Dead; Child Star in Films of the 1930’s.” New York Times. 24 Jan. 1992.

- Johnson, Erskine. “In Hollywood.” Daily Kennebec Journal. 1 Oct 1945:4.

- Lesem, Jeanne. Simpson’s Leader-Times. 5 May 1971: 9.

- Lester, John. “Freddie Bartholomew Should Try New Show.” Long Island Star-Journal. 21 Feb 1952: 24

- Lester, John. “‘Melody Scrapbook,’ On View Over at WPIX.” Long Island Star-Journal. 20 May 1952: 24.

- “‘Little’ Freddy Bartholomew Is Now Ad Executive of 40.” Racine Journal Times Bulletin. 12 Aug 1962.

- “Live Letter of the Week: Selected by The Old Codgers.” The Daily Mirror. 6 Mar 1976.

- “Loew’s State, New York.” The Billboard. 21 Dec 1946: 36.

- Marsh, Molly. “Notes on Being a Boy.” Oakland Tribune. 17 Nov 1935: 12.

- “More Bartholomews.” The Daily Mirror. 21 Oct 1937.

- “Mother of Boy Film Star Missing.” The Daily Mirror. 11 Apr 1936: 1.

- “Movie Star’s Mother Plans Custody Fight.” The Lima Sunday News. 12 Apr 1936: 2.

- “Music As Written.” The Billboard. 22 Apr 1950: 26.

- “Noted Actor to Appear in City at Junior High.” Evening Recorder. 2 Jan 1948: 2.

- Nugent, Frank S. “Little Lord Fauntleroy, a Pleasant Film Version of the Familiar Novel, at the Music Hall.” New York Times. 3 Apr 1936.

- “PTE Freddie Bartholomew Discharged.” The Argus. 13 Jan 1944: 12.

- Rawles, Obera H. “Freddie Bartholomew Anxious to Make More Movies and Use His New Men’s Dressing Room.” The Corpus Christi Times. 30 Aug 1937: 5-B.

- Reichardt, Nancy M. “Soap Scoop.” Brandon Sun. 25 Feb 1983.

- “Rosen Booking For Down Under.” The Billboard. 6 Nov 1948: 46.

- “‘Runaway’ Marriage: Freddie Bartholomew Married to Maele Daniele.” Cairns Post. 27 Apr 1946: 6.

- Shales, Tom. “Turner’s MGM Retrospective Comes Up Short.” Roanoke Times. 21 Mar 1992: E-2.

- Soanes, Wood. “Curtain Calls: U.S. Divorce From Films Is Prospect.” Oakland Tribune. 18 Nov 1946: 17.

- “Star Coming.” The Courier-Mail. 17 Nov 1948: 3.

- “Substitute Star: A Deputy for Freddie Bartholomew.” The West Australian. 3 Jun 1938: 4.

- “Tax Windfall for Boy Film Star.” Army News. 26 Dec 1944: 3.

- “Then and Now–Portway, Warminster.” Wiltshire Times. 27 Sep 2007.

- “Threat to Kidnap Boy Film Star.” The Canberra Times. 30 Nov 1936: 1.

- “25 Years’ Gaol. Man Who Threatened Film Stars.” The Mercury. 16 Apr 1937: 6.

- Ullyett, Kenneth, ed. “Freddie Bartholomew–The Truth.” The Daily Mirror. 16 Apr 1936.

- “Yesterday & Today in the Lives of Famous Folk.” The Record-Eagle. 15 May 1947.

Website Links:

- Bartholomew v. Bartholomew, 56 Cal.App2d 216. LawLink.com

- The Italia Conti Academy of Theatre Arts.

- Wikipedia: Freddie Bartholomew (This page has had a fantastic update since I began work on my Freddie project!)

- Wikipedia: William Dufty.

Primary Sources:

- Soldiers of the First World War – CEF. Library and Archives Canada. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/databases/cef/001042-119.01-e.php?id_nbr=27485

[phpbaysidebar title=”Freddie Bartholomew on eBay” keywords=”Freddie Bartholomew” num=”5″ siteid=”1″ category=”45100″ sort=”StartTimeNewest” minprice=”59″ id=”2″]

Cliff? I am … speechless. I knew you were the go-to-guy on Freddie, but this post just knocked me over. THANK YOU SO MUCH for all of your passionate, very hard work! Fans of Freddie, like me, are VERY grateful to you for it! (you should… oh, I don’t know…. maybe… *** write his biography ***)

Thanks so much @twitter-1590591:disqus I really appreciate that. This post is soooo long that I expect not many will get down this far, but I do hope the Freddie-fans are entertained if they do!

I’ll tell you, I very nearly turned this into an eBook (and maybe I still will to help out people on the go) but there are still a few questions that need to be answered and a few films I should probably detail a little more so I decided to save that for the next update. On TCM’s next Freddie-day. Which I hope happens! Thanks again!

I was watching “Captain’s Courageous” today on TV and suddenly got very curious about what ever happened to Freddy Bartholomew. Imagine my pleasure when I happened upon your wonderfully researched article. With a little more digging, this would make a terrific book. It’s really interesting and edifying to discover how people who have early incredible fame live out their lives. Thanks and good luck.

Thanks so much @fc9d7086c201ff907eaabd8bb37e374d:disqus I hope I managed to satisfy any curiosity you had in coming over. I think Freddie’s biography is made all the more interesting by such an unusual “Act 2”.

Congratulations on putting all this together, Cliff – a very interesting in-depth piece. I liked your discussion of the impression Bartholomew makes as an actor and the way we see through his eyes rather than just watching him. So far I have only seen two of his films, ‘David Copperfield’ and ‘Captains Courageous’, but I would agree with this from seeing his performances in these two.

I was interested in your descriptions of his other films and would like to see more of them – he certainly starred in adaptations of a lot of literary classics/period dramas, and that’s an area which interests me in particular, so I hope to track a few of them down and will keep my eyes open to see if any turn up on UK TV. A shame that he made so little money from his years of fame due to all the court cases, something which sadly seems to have happened to quite a few child stars over the years.

Thank you, @google-5c190b60953bd9f39343ba49126b58c4:disqus if and when I get to the next version of this I’d like to add a little more about a few of the films I just sort of name-checked in the current version. Well, at least you’ve seen the big two, those and ‘Little Lord Fauntleroy’ are the ones aired most often, at least over here in the States.

As I mentioned in a reply above Freddie seems to have had a very successful and unusual second Act where what appears to have been a very difficult post-WWII era for him turned out to be a wildly successful career in Advertising and TV. Good for him!

I just saw him in Anna Karenina for the first time on TCM and loved it. I definitely could relate to him when his father lied and told him his mother was dead. I wish that I had said the same thing back to my father when he told me to think of my mother as if she were dead. As far as his personal life, it’s shameful what his parents did once they found out he was a child star and wanted money.

@facebook-100000196337639:disqus did you see the bit from Basil Rathbone about how they managed that scene? It’s tucked somewhere up above but basically Rathbone wrote that he told Freddie his Aunt Cissy was dead to get that reaction out of him!

As for his parents, well. I’m a big believer in there being two sides to every story, but I’d really need someone to make a case for them before being able to give them more than even the slightest benefit of the doubt.

“The love that dare not speak its name” in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art, like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as “the love that dare not speak its name,” and on that account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an older and a younger man, when the older man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so, the world does not understand. The world mocks at it, and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.”

Thank you @facebook-672755654:disqus for classing the place up with some Oscar Wilde.

As a child I was totally captivated by Freddie. His elocution and the forthrightness he conveyed balanced by his delicate features and luminescent eyes I found mesmerizing. His portrayals whetted my appetite for the classics… After watching several of his movies some 60+ years later on TCM, I still find myself totally drawn to him whenever he appears on screen, striving to listen to his precise eloquent presentation that outshone most of his adult counterparts. I remember the tears shed while watching “Captains Courageous” and the vicarious feeling of bravery felt while watching “Kidnapped”. To me his portrayals were subtle and compelling rather than the more typical heavy handed forced nature of many young performers. Thank you so much for this in depth article; your dedication in researching is self evident. It demonstrate how much we are a product of our environment; in some instances able to surmount the deficiencies and in others simply succumbing to things totally out of our control. For me Freddie was a pressure valve, giving me the opportunity to escape the reality of life for an hour or two,,,,something that most children and adults need at times…the imagination that allows you to be conveyed at least for a short time to a plane where you are in control and not a victim of your circumstance. Again, gratitude for a reawakening of childhood memories of a person and time that I can recall with fondness.

Thank you @twitter-144208799:disqus for the very kind reply. Yes, Freddie was subtle compared to the others, I completely agree! He just sort of was and that’s saying a lot when you consider he often played some of the greatest characters from classic literature. I’m glad if I could help recall some of the pleasure that Freddie has given you over the years, makes this feel like a job well done. Thank you!