Above: Trade advertisement for The Shame of Temple Drake, Motion Picture Herald, February 25, 1933.

I hate issuing a “spoiler alert” for something that’s been around so long, but specifics and key plot points for both William Faulkner’s 1931 novel and Paramount’s 1933 film adaptation are mentioned, compared, and contrasted throughout this article.

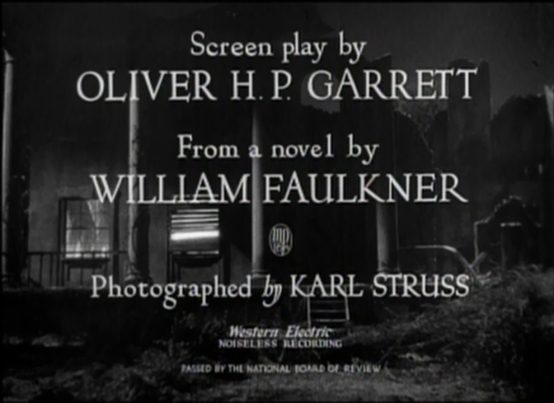

If you’re at all familiar with the source material, it’s hard to believe this movie was even made. Familiarity with the production notes makes the existence of The Story of Temple Drake even more unlikely. The movie is based on William Faulkner’s Sanctuary, a novel in which the leading character’s sexuality is awakened after an impotent gangster rapes her with a corn cob. Let’s try and get that past the Hays Office! No, even in the wild and woolly pre-Code era, nothing close to that is going to fly.

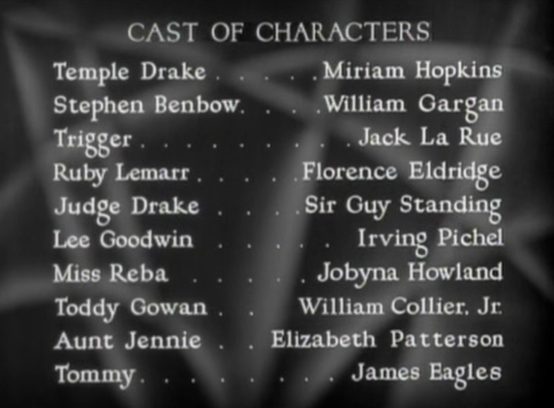

Paramount paid Faulkner $6,000 for film rights to Sanctuary in October 1932. Miriam Hopkins and George Raft were slated to star. Representatives from the Hays Office notified the studio of their objections to the material, later insisting that the title of Faulkner’s book not appear in any advertising for their film. Paramount responded with The Story of Temple Drake, a title that could hook those familiar with Faulkner’s book by way of its title character. The Hays Office rejected the original script, but after rewrites Paramount earned their approval to proceed with production by the end of January 1933.[1] George Raft was less enthusiastic.

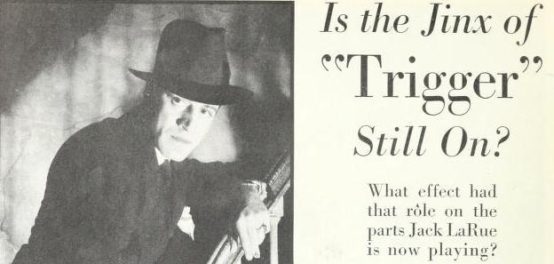

The option on Raft’s contract was due for renewal around this time, so it’s possible his labeling the part he was cast in—Popeye in the book, but for copyright reasons Trigger in the film—“screen suicide.”[2]

The option on Raft’s contract was due for renewal around this time, so it’s possible his labeling the part he was cast in—Popeye in the book, but for copyright reasons Trigger in the film—“screen suicide.”[2]

“They took up my option on the same mail they wrote me a letter suspending me from the payroll for refusing to play a part,” Raft said. “I was promised … ‘No more gangster and racketeer roles.’ Then they spring this on me.”[3]

The Scarface (1932) actor was a rising star at Paramount after films like Night After Night and Under-Cover Man (both 1932). “People have been good to me—they’ve liked me,” he said of his success. “If I had done what Paramount ordered me to do and played the part of Trigger they wouldn’t have liked me any more.”[4]

“That’s the way I got it figured out. That part was plain suicide for me—a fellow with my face. Any other actor might play it and maybe get away with it, but I look like that kind of guy. Not just on the screen—on the street, anywhere. There’d be just one thing for the public to think and they’d think it—‘George Raft, himself, is like Trigger.’”[5]

Paramount and Raft settled in mid-March, and Raft next appeared in Midnight Club (1933) for the studio.(The Trumpet Blows was originally announced as Raft’s return picture, but it wound up delayed until the following year.) [6]

Paramount wasted no time in replacing Raft with Jack La Rue, another actor who looked like “that kind of guy.” The switch caused a sensation in fan magazines, an unexpected benefit that an astute La Rue saw as a positive: “All this newspaper stuff and argument is going to be great publicity for the picture—and for me. Everybody will be curious to see the fellow who took the part George Raft wouldn’t play.”[7]

La Rue (1902-1984) turned professional actor out of high school when he joined Otis Skinner’s Blood and Sand road company. His Broadway debut came in The Crooked Square at the Hudson Theatre in late 1923, and he stuck on the Great White Way beginning with his appearance in Crime during 1927. La Rue’s most notable Broadway credit came opposite Mae West in Diamond Lil at the Royale in 1928. Throughout the late 1920s he also made a handful of bit appearances in movies filmed on the East Coast, especially for Paramount at their Astoria studio.

La Rue (1902-1984) turned professional actor out of high school when he joined Otis Skinner’s Blood and Sand road company. His Broadway debut came in The Crooked Square at the Hudson Theatre in late 1923, and he stuck on the Great White Way beginning with his appearance in Crime during 1927. La Rue’s most notable Broadway credit came opposite Mae West in Diamond Lil at the Royale in 1928. Throughout the late 1920s he also made a handful of bit appearances in movies filmed on the East Coast, especially for Paramount at their Astoria studio.

Jack La Rue arrived in Hollywood in 1932, and seemed poised for an immediate breakout when Howard Hawks cast him as Rinaldo in Scarface (1932). “I’d worked only four days when Hawks said to me, ‘Come into the projection room. I want you to see the rushes,’” La Rue said in a 1975 interview. La Rue viewed his footage with Hawks but saw nothing wrong. Hawks told him, “You’re taller than Muni and your voice overpowers his.’”[8] He was replaced by George Raft, a move that adds irony to the casting change in The Story of Temple Drake.

Raft famously flipped his coin to stardom in Scarface, while La Rue wound up working for Frank Borzage, who cast him as the priest in Paramount’s adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1932). “I was glad to get the part,” La Rue said in 1933. “I didn’t think ‘Farewell’ would mean much, but it turned out to be more important than any I ever played. On account of it, I got Raft’s role,” he said, referring to Trigger in The Story of Temple Drake.[9]

There were no hard feelings between the men. “George Raft and I are good friends,” La Rue said. “I don’t blame him, understand. He has more than I to lose—he has gone farther.” Raft, despite his distaste over the role didn’t blame Paramount for making the film, or La Rue for taking the role he had rejected. “I’m not criticizing Jack La Rue,” he said. “I’m only thinking of me—George Raft.”[10]

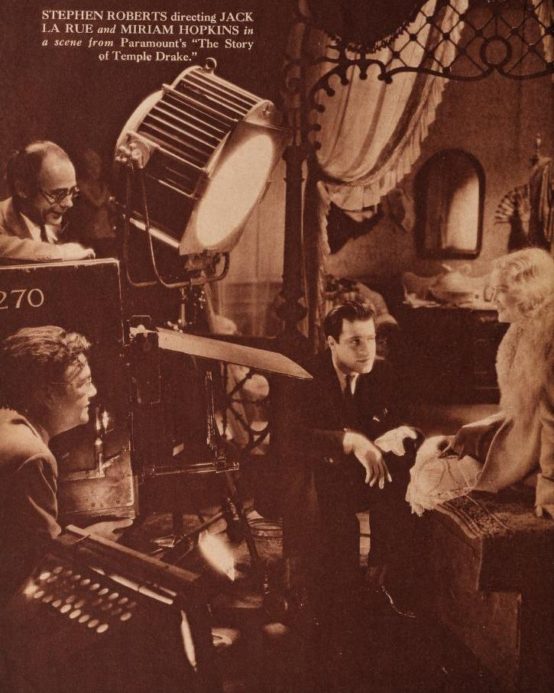

Above: “Trigger Jinx” title to story running Photoplay, November 1933.

La Rue’s Trigger moves as slow and deliberate as he speaks. Embodying danger, La Rue is often enshrouded by a haze of smoke, almost always with a freshly lit cigarette dangling from his lips. His well-dressed bootlegger looks as though he’s dropped out of some big city, Chicago or New York, to boss the grim backwoodsmen he’s forced to do business with. Those rural bootleggers are dressed in rags and based out of a dilapidated house with boarded windows and no electricity. Fueled by their own product, their minds are mush and their souls empty, the homemade hooch seemingly all that allows them to function in any capacity. A sober Trigger amuses himself by splitting the liquor jug from a blind man’s grip with a bit of indoor marksmanship.

Prohibition is still on, so there’s profit behind the boozing of these country folk, though their surroundings lead you to suspect Trigger earns the lion’s share. The room they’ve gathered in inside the Goodwins decrepit home is a speakeasy for drunks to gather. Toddy Gowan (William Collier Jr.) may be even more depraved than the regularly assembled group who belong there. Toddy is well born, a college man who learned to drink as part of his education. He carries a flask to power through his social life, but Toddy needs more than a sip here and there to feel fulfilled. After Temple Drake (Miriam Hopkins) fights off his advances in the parking lot at a society ball, Toddy quickly grows bored.

Above: Temple and Toddy (Miriam Hopkins and William Collier Jr.)

Temple teases him as far as propriety allows before going inside to dance. A Southern belle, Temple has been raised under the respectable eye of her grandfather, a judge (Sir Guy Standing). She can do no wrong by the old judge, though he’d like her to settle down and marry, preferably lawyer Stephen Benbow (William Gargan). But Temple teases and flirts with so many boys that she’s even the subject of bathroom graffiti, civil enough in content, though not so much so in its context (“Temple Drake is just a fake / She wants to eat and have her cake.”). There’s a special place in her heart for Stephen, but Temple is too confused by her awakening sexuality to commit herself to any one man.

Above: William Gargan and Miriam Hopkins

“Stevie, I’ve wanted to marry you ever since I was little. But I won’t. I can’t,” she confesses in a private moment on the balcony outside of the party she’s come to with Toddy.

“It’s like there were two mes,” she tells him. “One of them says, ‘Yes, yes, quick, don’t let me get away.”

“And the other?” Stephen asks.

“I won’t tell you. Or what it wants, or does, or what will happen to it. I don’t know myself. All I know is I hate it.”

Temple runs away from the party, from Stephen, and is passenger on a drunken hell ride through the woods with Toddy Gowan, who overturns his car on a hidden path nearby the Goodwins. It’s Trigger who shines a flashlight over their fallen bodies, pausing his beam on Temple’s bare legs. Temple is terrified, but Toddy is happy to be led to what had always been his ultimate destination anyway, Lee Goodwin’s place. Trigger abandons them for work, so the pair are led by Tommy (James Eagles), a slow-witted young man whose words drip out of his mouth.

Above: Trigger shines a light.

Thunder rumbles as they near Goodwin’s place, its threatening presence highlighted by cracks of lightning overhead. The scene is as unwelcoming as The Old Dark House (1932), only the misfits waiting inside this once stately structure have self-inflicted their insanity through extensive doses of homemade liquor. Toddy leaves Temple outside to rush in for his share of drink. Temple knows she shouldn’t go in. She peers between the boards slatted over the broken window and sees a table surrounded by drunken men. All men, until Ruby (Florence Eldridge) enters. Temple runs around the outside of the house until the weather finally forces her inside. She joins Ruby in the kitchen.

Above: Another old dark house.

She didn’t want to go in. The weather forced her to do so. Would she have gone in if she hadn’t spotted Ruby? Probably not, but the company of another woman offered some suggestion of safety. If Ruby could survive there, then the men probably wouldn’t tear Temple to pieces. But Temple is like a new piece of candy.

“Sit here, kid. Right on my lap,” one of the drunks (James Mason) says, grabbing Temple and propping her atop him.

Terrified, Temple calls to Toddy, who is face down on the table, dead drunk. Toddy finally rises and objects, but the man knocks him out with one punch.

Luckily, the men have work to do. They have to get their booze to town, and it’s suggested that they drop Temple and Toddy off along the way.

“Nah,” Trigger says. “You’re taking the drunk. Not her.”

Temple is a prisoner of the house. Ruby tries to make her comfortable, but Ruby’s main interest is keeping her man, Lee Goodwin (Irving Pichel), away from Temple. The men try to get to her before they go, but one is interrupted by Tommy, who’s proving himself a useful watchdog. The other—Trigger—is driven away by Ruby.

Above: Florence Eldridge (Mrs. Fredric March) as Ruby.

“Well, now you’re satisfied,” Ruby says, scolding Temple. “You got ‘em all fighting over you. You nice women,” she says, practically spitting the words. “I know your kind. You get a kick out of playing the kids. Burning their gas, eating their food, spending their money. And what do you give ‘em? Always got away with it before, ain’t you? And now you’re scared. Because these ain’t kids, they’re men.”

Ruby moves Temple from the bedroom inside the house outside to the barn, where Tommy stands guard over her overnight.

Temple survives the threatening night; the next morning is sunny and beautiful. But Trigger has returned from the liquor haul. Tommy is awakened from his post by the tapping of the blind man’s cane. When Tommy checks on Temple, Trigger scales a ladder leading to the hayloft out of view behind him. Temple reclines on the hay amid a pile of corn cobs as the sun shoots through the wooden slats that seem to safely enclose her. She’s distracted for a moment by footsteps over head. A trap door opens revealing Trigger, who makes eye contact with Temple for a moment before descending to join her in the tight confines of her enclosure. Tommy checks in once more, but Trigger shoots him dead. Trigger and Temple exchange stares, and then he approaches her, passing out of the camera’s view as he nears Temple. We see nobody, but hear Temple’s scream as the scene comes to an end.

Above: Trigger descends (Jack La Rue with Miriam Hopkins).

“It was an-y-thing but done in a distasteful way,” Miriam Hopkins told film historian John Kobal many years later.[11] But what about the corncob? Wasn’t Temple Drake raped with a corncob? Yes—in Faulkner’s novel.

“I offer as evidence this object which was found at the scene of the crime,” the District Attorney says in the book. “He held in his hand a corn-cob. It appeared to have been dipped in dark brownish paint.”[12]

In March 1933, the Hays Office warned Paramount boss Adolph Zukor about including a shot where a corncob is picked up and examined following Temple’s rape. The American Film Institute notes about The Story of Temple Drake also state that the Hays Office forced the scene to take place inside of the barn rather than the corn crib of Faulkner’s novel, and that no corncobs were to be either shown or referenced.[13] They are shown. Attention is not called to them, but if you’re looking for them, they are there.

Above: Temple tries to sleep … corn cobs at top right.

The film works on multiple levels to this point before veering further away from its source material afterward. Trigger creeps into the barn and rapes Temple Drake, but if you know the book you’d swear he did it with a corn cob because he’s impotent. Those details leave viewers who are unfamiliar with the book wondering what they missed. The rape scene is necessary to the story, and its implications work on different levels in the film depending on whether you’ve read the book or not.

“If you can call a rape artistically done … it was,” Hopkins said. “As a matter of fact, If anybody would say to me: ‘What is one of the finest pictures you’ve made?’ I would say: ‘Sanctuary.’”[14]

Miriam Hopkins was a Paramount contract player at the time of The Story of Temple Drake. She had turned to acting after a broken ankle halted her burgeoning dance career in 1922. After some early highs and lows, Hopkins made good on Broadway in dramatic productions such as Puppets (1925) and An American Tragedy (1926), as well as the comedy Excess Baggage (1927). Hopkins signed with Paramount and made her feature film debut in Fast and Loose (1930).

During her first several months under contract to Paramount, Hopkins was able to work at their Astoria, New York, studios during the day, while continuing to moonlight on Broadway in the evenings. She appeared in The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), the first three films for director Ernst Lubitsch, while in New York, but after that the studio shipped her out to Hollywood as they scaled back east coast operations.

During her first several months under contract to Paramount, Hopkins was able to work at their Astoria, New York, studios during the day, while continuing to moonlight on Broadway in the evenings. She appeared in The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), the first three films for director Ernst Lubitsch, while in New York, but after that the studio shipped her out to Hollywood as they scaled back east coast operations.

“When five weeks passed and the studio ignored me, I marched in and insisted on testing for the part of a night club singer.”[15] This was for Hopkins’ first film in Hollywood, Marion Gering’s 24 Hours (1931), a movie that did little for her reputation at that time, but which holds up well today. Hopkins next worked for director Rouben Mamoulian opposite Fredric March in the classic Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931). Hopkins had hoped to play Jekyll’s love interest in the film, but Mamoulian convinced her otherwise: “He said: ‘It’s three scenes. It’s dull! You want to play the little cockney streetwalker of this, it’s the greatest.’”[16] Rose Hobart played the dull part; Hopkins made much more of an impression as the prostitute.

She next appeared in Two Kinds of Women (1932) for director William C. de Mille (Cecil’s brother); as a taxi-dancer opposite Jack Oakie in Dancers in the Dark (1932); and opposite George Bancroft for director John Cromwell in The World and the Flesh (1932), a drama set during the Russian Revolution. Then Lubitsch brought her back for another classic, Trouble in Paradise (1932) with Herbert Marshall and Kay Francis.

Known for stealing scenes and being difficult to work with, Miriam Hopkins is best remembered today for feuding with legendary star Bette Davis during two later films, The Old Maid (1939) and Old Acquaintance (1943). But Hopkins was on her best behavior and did her best work for the men who are remembered as her best directors. “Me temperamental? I never was,” Hopkins said in 1961.

Above: Hopkins with Bette Davis in Old Acquaintance (1943).

“Proof of that is that I made four pictures with Willie Wyler, who is a very demanding director. I made two with Rouben Mamoulian, who is the same. Two [sic] with Ernst Lubitsch, such a dear man.”

Mamoulian didn’t think she was difficult. “She was tenacious,” he said, “but when she discovered that someone could give her something better than she had thought of, she became pliable, and you could get all kinds of things from her that are unavailable from more malleable actresses.”[17]

Hopkins was scheduled to star in No Man of Her Own opposite MGM loan-out Clark Gable when Paramount bought screen rights to Sanctuary.[18] Paramount had promoted the coming Gable-Hopkins teaming for months, but temporarily dropped the entire project after the Hays Office rejected the script as too steamy.[19] Hopkins pulled out of the film for good in November 1932, with the excuse of “not liking the story.”[20] She was replaced by Carole Lombard, making No Man of Her Own required viewing for anyone who wants to see Hollywood’s future royal couple, Gable and Lombard, in their only movie together.

If No Man of Her Own was too hot for the censors, than Miriam Hopkins went out of the frying pan and into the fire with her next assignment: The Story of Temple Drake.

Above: Temple during the ride to Miss Reba’s.

Hopkins appears frozen with concern—or is it shame—as La Rue drives her off Goodwin’s property that morning. Ruby sees the pair leave, but Lee Goodwin cuts her short to tell her that Tommy’s dead. When Goodwin goes to town to report the killing, he’s arrested and charged with murder. Goodwin initially refuses an attorney: “Nobody’s got nothing on me. It’s up to them to prove it, ain’t it? Besides, I ain’t got no money.” The judge appoints Stephen Benbow as Goodwin’s defense.

“If I talk to you, nothing can save me,” Goodwin tells Stephen, showing him a bullet hole in the wall of his cell and the bullet casing that whizzed by him from across the way the night before. Goodwin figures he has a better chance of surviving the trial than he does Trigger. Ruby, who sits by loyally, cradling their baby, lets Trigger’s name slip, giving Stephen enough of a lead to follow-up for his court-appointed client.

Above: Stephen and Lee Goodwin (William Gargan and Irving Pichel)

Meanwhile, Trigger places Temple in a room at Miss Reba’s place—a local whorehouse.

“I’m not keeping you,” Trigger tells her. “If you want to go back to that town and to your grandfather, go ahead,” the implication being that Temple isn’t courageous enough to choose that path and confront her shame. Trigger moves from the door towards Temple with tight close-ups of La Rue and Hopkins emphasizing his menace and her fear and confusion. “I ain’t hurt you none,” he tells her. “Spotted you the moment I seen you. You holler and you faint, but—”

“No,” she says, her voice barely a whisper.

“You’re crazy about me.”

“No.”

“You’re going to stay,” he says. “You’ll like it here.”

She does like it—in the book—though the “it” is the sex, not necessarily Trigger. This is where Faulkner’s subject matter becomes too sensitive for the movie to handle. The movie continues to work and entertain on its own level, but it becomes a different story than what Faulkner wrote. The movie cannot even hint at Trigger’s impotence, whereas in the novel it leads to his next bit of depravity: Faulkner’s Popeye brings in another man, Red, to have sex with Temple while he watches, unable to do anything more. Temple later seeks out Red for another encounter, leading to Red’s murder at the hands of Popeye. There is no Red in the movie, nor any character taking on a role similar to this in any way. In the movie, Temple is held captive by her shame as much as Trigger, leaving whatever goes on behind their bedroom door at Miss Reba’s to our own imaginations.

The only time that Temple likes it in the movie is when she pretends for Stephen’s benefit after he comes to Miss Reba’s seeking out Trigger in relation to the Goodwin murder case. Stephen opens the door to Trigger’s room and is horrified when he sees Temple there. Practically speechless, Stephen threatens Trigger, but Temple notices Trigger reaching to his pocket for his gun. Temple then pretends that she’s Trigger’s woman, and that she likes being so, for benefit of saving Stephen’s life.

“He didn’t bring me here. I came because I wanted to come. And I stayed because I wanted to be here,” she tells Stephen.

Above: Temple plays a part (Gargan, Hopkins, and La Rue).

Temple sits on Trigger’s lap, telling him not to worry about Stephen, “he’s just a jealous busybody.” She takes the cigarette from between Trigger’s lips and kisses him before taking a deep drag off of his smoke. Trigger is placated. He smacks her on her rear end, smiles, and says, “Okay, kid.”

Trigger claims ignorance as to the charge against Goodwin. Temple confirms Trigger’s alibi, claiming they were right there in the room at Miss Reba’s on the night of the murder. Stephen leaves subpoenas for each of them, which Trigger tears up the moment Stephen departs.

“Poor lug … He don’t know yet how near he came,” Trigger says, removing his pistol from his pocket for a quick inspection. “I’d have let him have it sure, if you hadn’t stepped in when you did … You came through for me. Stood up for me against one of your own kind.”

Trigger finally seems—happy. He’s content, as though he’s finally won the girl he’s been courting. But Stephen’s visit has exposed Temple’s shame: her secret is out in the open. So she’s packing.

“It was a rib,” Trigger finally realizes. “You put on an act for me so I wouldn’t croak the boyfriend.”

He stops her from leaving the room, realizing, “… now you’re going to put the finger on me.”

“I’m not going back,” Temple says. “I’ll never go back. I’ll just disappear.”

That changes after she kills him.

The Shame of Temple Drake was a working title for this film, and it would have proved accurate. The hero, Stephen Benbow, eventually gets Temple to testify, though he relents before exposing her shame to the court. Before he gives up, Stephen arouses Temple’s pride by invoking the long line of proud Drake family members. It’s only when Stephen stops questioning her—when he values Temple over his own values of justice—that Temple rescues him with a full confession that fingers the now departed Trigger and frees Lee Goodwin.

It’s a very different path from the novel.

There is no romantic attachment between Stephen and Temple in the book. He only knows her in relation to this case. When Temple takes the stand in Sanctuary, Popeye is still alive. And she doesn’t tell the truth. Lee Goodwin is convicted and would hang, if not for the lynch mob that burns him to death before he ever has a chance to face the noose. While Temple had to kill Trigger in the movie to free herself, Popeye doesn’t have to pay for Tommy’s death in the book, where he also gets away with murdering Red. Not directly, at least. Faulkner’s Popeye is done in by mere coincidence. He’s arrested in another town for a murder he didn’t commit. He accepts the charge, and is executed for a crime committed by somebody else.

… Random Louise Beavers sighting, working the door at Miss Reba’s …

“This book was written three years ago. To me it is a cheap idea, because it was deliberately conceived to make money,” William Faulkner famously wrote in his 1932 introduction to the Modern Library edition of Sanctuary.

“I took a little time out, and speculated what a person in Mississippi would believe to be current trends, chose what I thought was the right answer and invented the most horrific tale I could imagine and wrote it in about three weeks.”[21]

This sounds like a hack rushing something hot to market, but Faulkner isn’t referring to his finished product.

When he first sent Sanctuary to Harrison Smith at Cape & Smith publishers, Faulkner claims that Smith’s response was, “Good God, I can’t publish this. We’d both be in jail.”[22] Faulkner went to work on As I Lay Dying.

Faulkner wrote that he had all but forgotten about Sanctuary at this time, “just as you might forget about anything made for an immediate purpose, which did not come off.” He received the galleys for Sanctuary after As I Lay Dying was published. “I saw that it was so terrible that there were but two things to do: tear it up or rewrite it.”[23] He chose the latter action. It is that revised version of his manuscript that Cape & Smith published on February 9, 1931.

Faulkner did not want the Modern Library introduction included in future editions from Random House. The damage was done though, Sanctuary is forever labeled by many as “a cheap idea … deliberately conceived to make money,” but Faulkner was only applying those ideas to his original intention.

Faulkner’s dialects have always made him a difficult read for me. I had read Sanctuary several years ago, both because of its comparative brevity and its notoriety. It didn’t stick with me. In fact, my only memories were of a negative experience. I purchased another copy in anticipation of this essay, tackling it well in advance of revisiting the Paramount film, just in case it prove as difficult as I remembered. And it was not an easy book, but it did get through to me this time. It’s unpleasant, yet haunting. I’ve found myself dwelling on its details the past few weeks and am surprised to find that I enjoy my memories of Sanctuary better than I did the actual reading of it.

Above: Director Stephen Roberts, 1927 image.

Temple is practically catatonic after Trigger rapes her. In the novel it leads to her encounters with Red, the stud Popeye supplies for his own entertainment. A stud Temple eventually seeks out for pleasure on her own. There is no pleasure in the movie. The only area of confusion in the movie comes when Trigger tells her she’s free to leave. Her shame keeps her from leaving, but is that enough of a reason to stay, without at least implying pleasure? It’s not how I view the scene. I don’t think she’s really free until after she kills Trigger. Which she doesn’t do in the novel.

The movie applies its just desserts to Temple by rewarding her only after she saves Stephen. Her reward, another movie standard, is Stephen’s protecting arms. Temple gives her testimony, her confession, and then faints. Stephen picks her up and carries her out of the courtroom with her concerned grandfather trailing along beside him. “Be proud of her, Judge. I am.”

The moral uproar surrounding The Story of Temple Drake extended beyond George Raft’s refusal to play Trigger. P.S. Harrison, founder of Harrison’s Reports and oftentimes a one-man moral watchdog, addressed his complaints directly to the head of Paramount, Adolph Zukor. He received and published replies from Zukor underling Russell Holman, who assured Harrison that Dr. James Wingate, former Chairman of the New York Censorship Board, approved Paramount’s script and added that “‘sexual perversion and degeneracy’ are utterly and entirely absent.” Harrison wasn’t satisfied, noting that Wingate was not the final word on what was or wasn’t acceptable, and further scolded Paramount for choosing material solely because of the “sordid notoriety” of its source material, adding, “There isn’t a single situation that can be pictured.”[24]

Above: From the June 1933 issue of Broadway and Hollywood Movies via Lantern.com search.

Harrison was far from the exception in panning the material as unacceptable. The Hollywood Reporter suggested “the Academy might create a special award for it. ‘The Most Unnecessary Picture of the Year.”[25] The New York Daily News despised the film, stating “it should never have been bought and never produced … the scrap heap is where the picture belongs.” Also from New York, the American called it “a shoddy, obnoxiously disagreeable melodrama.”[26]

New York’s Herald-Tribune picked up on some of the charms of the movie: “It is so daring a film, so frank and unabashed in its narrative and so maturely sinister in its implications that it possesses an undeniable fascination,” while other critics thought Paramount had done as well as it could, given the difficult source material. “The richness and atmosphere is somewhat missing as are the more spectacular elements of degeneracy,” said the New York Sun, “But as talkies go, Temple Drake is original and dramatic melodrama.”[27] Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times was impressed, “considering the changes that were to be expected in bringing this novel to the screen, the producers have wrought a highly intelligent production.” Hall admitted, “there are loopholes in the story as it comes to the screen, but the adroitly sustained suspense atones for such shortcomings.”[28]

Above: The shadow of La Rue.

Negative reviews didn’t impact The Story of Temple Drake, at least not upon its release. Hollywood Reporter said, “those pan reviews written by some of the local dailies … attracted people to the Paramount box office instead of keeping them away.” The Story of Temple Drake opened so strong at New York’s Paramount that it topped box office receipts for the entire previous week in just its first three days playing at the theater.[29]

When it ran into trouble with Catholics in Rhode Island, Providence’s police censor contacted exhibitors in Boston and New York to see if The Story of Temple Drake had caused them any trouble. He was told they faced “no opposition” to the film. The police censor held a preview for the press and clergy, and gave the film his approval afterward. The print shown in Providence supposedly had several cuts from what had played in New York, but the censor said he himself had made no deletions.[30]

Above: The shame of Gargan.

In an article about movie censorship in Modern Screen, published about a year after The Story of Temple Drake’s release, author James B.M. Fisher dedicated several paragraphs to New York’s notoriously tough film censors, but made a point of stating Temple Drake was released there without any cuts. Fisher added that “Pennsylvania sheared material amounting to three typewritten pages from it and Ohio two.”[31] The Pennsylvania mention is corroborated by Variety who reported the film “was passed through after a flock of eliminations had been made.” Ironically, Variety’s mention of The Story of Temple Drake was because it was replacing Bed of Roses (1933) at the Stanley Theatre after state censors rejected the latter film in its entirety.[32]

Charles S. Aaronson of Motion Picture Herald admired The Story of Temple Drake more than any other contemporary critic I could find. He began his review complimenting Paramount for its “grave courage” in even attempting to produce a film based on Sanctuary. Aaronson wrote:

“Paramount has done remarkably well by the material at hand, contriving, with care and intelligence, to disregard the numerous inherently objectionable features of the Faulkner novel, to avoid the motion picture pitfalls with which the original was crowded, and at the same time to turn out a motion picture of definitely strong dramatic power, containing much which should be found popularly appealing.”[33]

Temple Drake returned in William Faulkner’s sequel to Sanctuary, Requiem for a Nun, published in 1951. The rights to The Story of Temple Drake were purchased by Twentieth Century Fox, who used both Sanctuary and Requiem for a Nun as source material for their 1961 release Sanctuary, which was directed by Tony Richardson and starred Lee Remick, Yves Montand, and Bradford Dillman. This time around Remick’s Temple Drake is more responsive to the Popeye character—here dubbed Candy Man and played by Montand—but censors still proved too stringent for a truly faithful adaptation. The earlier movie remains superior.

Above: Trade ad for Sanctuary, sourced from Box Office magazine, February 27, 1961.

In celebration of Paramount’s sixtieth anniversary, Miriam Hopkins attended a showing of The Story of Temple Drake at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) on July 12, 1972. According to MoMA’s website, Twentieth Century-Fox donated their original print of the film to them in 1974. Turner Classic Movies (TCM) got in touch with the Museum and they collaborated on a restoration that premiered at MoMA’s “To Save and Project” series in October 2010.[34] The movie first played on TCM September 14, 2011, and continues to play on the channel a few times each year. As of this writing The Story of Temple Drake is not yet available on home video.

The Story of Temple Drake ranks with releases such as Red-Headed Woman (1932), Baby Face, and I’m No Angel, (both 1933) as one of the more notorious releases of the pre-Code era. The reputation is deserved, though notoriety today translates to boldness. Unlike those other films, The Story of Temple Drake boasts important literary origins, and while the film is not nearly as daring as the story it is based on, it is a high quality release featuring superior writing, direction, cinematography, and acting. Jack La Rue is one of the most menacing screen scoundrels that you’ll ever encounter, and Miriam Hopkins gives a performance that underscores her reputation as one of the finest screen actresses of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Above: Hopkins in your face.

This article first appeared more than one year ago in Classic Movie Monthly #5 for Kindle (no longer available). While there were only small changes to the text, most of the images (including all screen captures) are new to this post.

References

1. “New ‘Drake’ Treatment,” Hollywood Reporter, January 24, 1933, 3; “Temple Drake,’ Alias ‘Sanctuary’ Started,” Hollywood Reporter, January 31, 1933, 1.

2. “Raft Will Quit Rather Than Play in “Temple Drake,’” Hollywood Reporter, February 13, 1933, 1.

3. Dorothy Calhoun, “Will His First Big Role Make or Break Jack La Rue?” Movie Classic, May 1933, 58.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. “Raft-Paramount Argument Settled,” Hollywood Reporter, March 18, 1933, 1.

7. Calhoun, 58.

8. “Yesterday’s Stars: La Rue Doesn’t Like Gangster Stereotypes,” Pottstown Mercury (PA), November 8, 1975, 40.

9. Hubbard Keavy, “Screen Life In Hollywood,” Altoona Tribune (GA), April 26, 1933, 4.

10. Calhoun, 58.

11. John Kobal, People Will Talk (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 355.

12. William Faulkner, Sanctuary, in Novels 1930-1935 (1931; repr., New York: Library of America, 1985), 376.

13. “The Story of Temple Drake,” AFI: Catalog of Feature Films, accessed January 6, 2017, http://www.afi.com/members/catalog/DetailView.aspx?s=&Movie=4944.

14. Kobal, 356.

15. Erskine Johnson, “In Hollywood,” Gloversville and Johnstown Morning Herald (NY), August 25, 1950, 4.

16. Ibid.

17. George Eells, Ginger, Loretta and Irene Who? (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976), 101.

18. “Gable’s Paramount Film,” Film Daily, June 1, 1932, 6.

19. “Par Ditches ‘No Man’ After Story Troubles,” Variety, September 27, 1932, 4.

20. “For Legal Advice,” Variety, November 22, 1932, 6.

21. Faulkner, 1029-30.

22. Ibid., 1030.

23. Ibid.

24. P.S. Harrison, “The Case of ‘Sanctuary,'” Harrison’s Reports, March 18, 1933, 41.

25. “Best Example of Bad Taste Yet Seen” Hollywood Reporter, May 11, 1933, 4.

26. “New York Reviews,” Hollywood Reporter, May 10, 1933, 2.

27. Ibid.

28. Mordaunt Hall, “Miriam Hopkins and Jack LaRue in a Pictorial Conception of a Novel by William Faulkner,” New York Times, May 6, 1933, accessed December 27, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9904E4DF1538E333A25755C0A9639C946294D6CF.

29. “‘Temple Drake’ OK At N.Y. Paramount,” Hollywood Reporter, May 10, 1933, 4.

30. “Severe Opposish, But ‘Temple’ OKed in Prov.,” Variety, May 23, 1933, 21.

31. James B.M. Fisher, “Here’s What the Censors Took Out,” Modern Screen, July 1934, 111.

32. “Penn. Censors Nix ‘Bed,’ But ‘Temple’ OK,” Variety, July 11, 1933, 6.

33. Charles S. Aaronson, “Showmen’s Reviews: The Story of Temple Drake,” Motion Picture Herald, May 13, 1933, 22.

34. Anne Morra, “Temple Drake: Was She Ever Lost?” Inside/Out: A MoMA/MoMA PS1 Blog, December 8, 2011, accessed January 5, 2017, https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2011/12/08/temple-drake-was-she-ever-lost/; Katie Trainor, “Out of the Vaults and onto the Screen,” Inside/Out: A MoMA/MoMA PS1 Blog, October 14, 2010, accessed January 5, 2017, https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2010/10/14/out-of-the-vaults-and-onto-the-screen/.

[…] Jahr, bevor man Clark Gables nackten Oberkörper im Kino sehen konnte, war dieser Film der Skandal Amerikas. So ausgezogen-angezogen war die kleine Temple Drake in ✺The Story […]