Change the names—including the title—and the second screen version of Babbitt works better than you’d expect. In fact, a similar movie, minus such influential source material, had proved popular just a couple of months earlier when Babbitt director William Keighley and Babbitt stars Guy Kibbee and Aline MacMahon were teamed for Big Hearted Herbert. They’re both silly movies, folksy enough to justify elevating Guy Kibbee towards the top of the billing as the perfect embodiment of the average middle-aged, middle class everyman for us to laugh at and relate to as he struggles and blusters through his ordinary day. Aline MacMahon costars as his wife in both movies, two of ten films total that they appeared in together. She’s the levelheaded smarter half of the couple whose quick wits save her husband, and so the family, from himself.

In Babbitt this is an invention of the screenwriters. In the Sinclair Lewis novel Babbitt’s wife is just as bad as Babbitt. Worse even, as she rallies husband George to stick on the straight and narrow path he has always traveled as one of Zenith’s respectable, proper men of influence—her attitude in the book is similar to that of Fran Dodsworth in Lewis’s Dodsworth, at least as portrayed by Ruth Chatterton in the 1936 film adaptation (It’s the next Lewis novel I plan to read). The book Babbitt is a character study that unfolds over several hundred pages, whereas the movie is too short for subtlety and too afraid of insulting any portion of its audience to bother with much of the author’s cutting satire. The movie only has time to poke fun at Guy Kibbee’s character, not society at large.

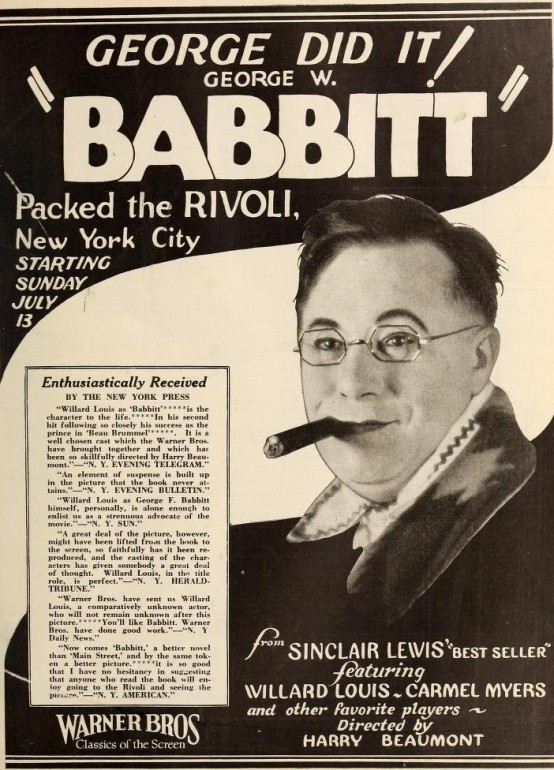

Babbitt really shouldn’t work. It’s a Great Depression-era adaptation of a novel that helped define the previous decade. Warner Bros. first made it in its own time, and while some film critics praised the 1924 version of Babbitt, it was a major flop at the box office. While the term “Babbitt” secured a place in the American lexicon practically from the time of the book’s publication in 1922, nobody has remade the blockbuster Sinclair Lewis novel as a movie since this second attempt in 1934 (And the 1924 silent film is lost, so Guy Kibbee is all we’ve got once you put the book back on the shelf).

Lewis had emerged as an important author a couple of years earlier upon publication of his divisive small town bombshell Main Street in 1920. That book caused an unexpected firestorm, and though some dispute that that was Lewis’s original intention, there’s little doubt Babbitt was a conscious effort by the author to capitalize and do more of the same. Babbitt was an even more sharply satirical novel that zeroed in on a vacuous American middle class ruled by a conformity that rewarded and sustained yes men like George Babbitt. Confident within his crowd, but cowardly when breaking from his familiar bunch, Babbitt’s eventual attempt at individuality is flawed by his inability to overcome the stern stares and hostile rebukes of those he’s surrounded himself with and aspired to be like. Lewis and much of his work are so closely identified with the 1920s that it’s hard to imagine why Warner Bros. would try to transfer already difficult subject material to New Deal America, but then I am probably thinking about it more than they did.

Sinclair Lewis had followed up Main Street and Babbitt with Arrowsmith, Elmer Gantry, and Dodsworth on his way to becoming the first American writer awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1930. By 1934 he remained the sole American found on that list of prizewinners. His popularity waned and never again would Lewis put his finger on the pulse of America as he had all throughout the 1920s, but the author’s top books carried extra box office potential at this moment in 1934 because of the stir Walter Huston was then creating on Broadway in Dodsworth.

It’s no surprise that the movie version of Babbitt doesn’t want to make its viewers as uncomfortable as Lewis had with his novel. That’d be courting bad box office. Variety saw the film as a “smooth, pleasant, but trite story of small town life.” It “carefully avoids ridiculing and thus should bring no objection from those large bodies of men who take their civic and fraternal activities seriously,” said the Motion Picture Herald reviewer after Babbitt’s preview. Somehow the spirit of Lewis’s novel is retained in what is a very polite adaptation. The book is filled with humor, but a lot of what is funny about Babbitt comes out the author’s jeering tone. George F. Babbitt is a very hard man to like on the page. Guy Kibbee is a lovable old fool no matter the title of the movie. Lewis reveals the dark side of Babbitt through the character’s thoughts in the book: ignorance mixed with flashes of pride that build towards independence almost always snuffed out by fear of what others think and say. He’s got too much to lose. A stern stare from a fellow club member is all it takes to give a rebellious Babbitt the jitters. Guy Kibbee keeps nothing bottled up. He wears all of his emotion on the outside. We can see ourselves in Babbitt as portrayed by Kibbee, but we don’t want to recognize the more flawed aspects of Babbitt revealed in the novel.

Above: Kibbee’s Babbitt with his secretary, played by Mary Treen. Miss McGoun pays Babbitt very little attention in the novel where she’s one of the first women he imagines having an affair with. In the movie Treen is perpetually amused by her foolish (and sexless) boss.

I found Babbitt a very trying character until well past the book’s midway point when he begins to rebel. He keeps his youth alive through best friend Paul Reisling, but Paul is just a more idealistic version of Babbitt. He’s followed the same path as a businessman, but he’s a sharper wit who understands what they’ve given up to be a part of the American Dream and he hates himself for it. That Paul still exists in the movie, where he’s played by Minor Watson, but he also carries the weight of failure as the only one of Georgie’s clan affected by the Great Depression.

We first see Paul when Georgie spots him entering a pawn shop to hock his prized violin. Babbitt comes to his best mate’s rescue by slipping Paul a hundred bucks for the violin, but adding that Paul should hang onto the instrument for now since he’s too busy at the moment to take those lessons he’s been meaning to get around to. It’s one of Babbitt’s most endearing moments in the movie. Babbitt then buys Paul a drink while dreaming up their escape to nature, away from their wives. Lewis gave Paul his violin, but otherwise only this last part is Sinclair Lewis and he let the boys have their vacation, supplying Georgie with fond memories to dwell upon and make his life all the more miserable later in the novel. They don’t make it beyond the camping supply store in the movie. Paul’s wife Zilla (Minna Gombell) remains the nagging villain she was in Lewis’s book, but Paul’s business failure gives her something more concrete to nag him about in the movie. She emerges as a cartoon in each version, too much of a villain for us to much fault Babbitt for sticking by Paulibus’s side after he shoots her.

Babbitt’s loss of Paul inspires him to reach for something more in both the book and movie. His oldest friend had always provided Babbitt a connection to his youth and idealistic memories that Babbitt has romanticized over time. Babbitt begins to break away from the sameness of his crowd after friends and acquaintances, even his own wife, speak out against Paul. In the novel he begins associating with a radical politician who he had been friends with in school and carrying on an affair with another woman, Tanis Judique, while trying to keep up with her hard-partying crowd. The politics are dropped in a movie so inoffensive that it even invents a fictional fraternal order rather than risk insulting any real-life Elks, Rotarians, or other club members. Babbitt was released at the end of 1934, several months after enforcement of the Production Code began, so his affair with Miss Judique is downplayed in the movie, more officially presented as an ardent longing for companionship on Georgie’s part. Instead of representing the deeper midlife crisis that she was in the book, Tanis Judique is turned into a blackmailing supervillain in the film. Well, we knew she’d have a bit of an edge to her when Claire Dodd showed up in the part, didn’t we?

To anyone who’s seen enough old movies to know these stars by name, it’s no surprise that Guy Kibbee is outsmarted by the cagey Claire Dodd character and, unless you’ve read the novel (much more likely in 1934 than today), even less of a surprise when top-billed Aline MacMahon—yes, Mrs. Babbitt comes first in these credits—rides to Kibbee’s rescue after their hilariously loyal and supportive son (Glen Boles) blows his cavalry horn.

The result is a movie that’s not entirely Babbitt, but one that’s not bad either. Variety nailed it when it said Babbitt was “not big time stuff,” but it plays as a better than average comedy of the era as long as you’re not looking for the movie to compete with the book. It does help to have read the novel, even if none of the previous paragraph actually occurs in the book. But if you’ve read the book, or are at least familiar with what it revealed, then you can spot a little bit of its darkness at the fringes of this otherwise lighthearted release. Minor Watson’s Paul still manages to upset Babbitt’s mindset and Babbitt’s other acquaintances, especially those played by Alan Hale and Berton Churchill, still reveal an unsettling iciness when Babbitt goes against the grain of society’s expectations. And nobody’s laughing when a policeman sends Georgie on his way after he’s caught eyeing the distance from the bridge he stands upon to the chilly waters below.

The movie ends on a much happier note than the book even if the actual result is much the same, a return to sameness.

As of this writing Babbitt has not yet been released on home video, but the First National-Warner Bros. release does show up on Turner Classic Movies every so often.

Leave a Reply