Chester Morris was an early Academy Award nominee who starred in a handful of pre-Code classics opposite some of Hollywood’s most glamorous and best loved actresses, but is best known for portraying reformed criminal Boston Blackie in a series of fourteen “B” movies for Columbia during the 1940s.

Chester Morris was an early Academy Award nominee who starred in a handful of pre-Code classics opposite some of Hollywood’s most glamorous and best loved actresses, but is best known for portraying reformed criminal Boston Blackie in a series of fourteen “B” movies for Columbia during the 1940s.

“Blackie kind of messed up my career. Even now the public usually visualizes me as Blackie. Only someone like Logan would cut through and cast me in something else.” — Chester Morris, 1958, when he was appearing in Blue Denim for Joshua Logan.

He was born John Chester Brooks Morris in New York City, February 16, 1901, to a show biz family that produced show biz kids. His father, William Morris (1861-1936), had been on stage since 1875 and made a few film appearances including a brief run as an early ‘30s character actor (Among other parts he was ”Ham, old egg”, Warren William’s co-conspirator in 1932’s Skyscraper Souls). Chester’s mother, Etta Hawkins (1865-1945), was a popular stage comedienne around the turn of the century.

Chester was the the Morrises second-born son. His older brother, Gordon (1898-1940), was an actor with some movie screenwriting credits and younger brother, Adrian (1907-1941), a very active bit actor throughout the 1930s until the time of his death. A sister, Wilhelmina, a year younger than Chester, was also said to be in the family act and is credited as having made a hit as the warden’s daughter in The Criminal Code on Broadway.Morris actually made his film debut in 1917 as rival suitor to Gladys Leslie in An Amateur Orphan, described at the time as one of Leslie’s “poor little rich girl” roles. Morris appeared in a few other silent films, but he really made his first major mark on the legitimate stage. He’s said to have had some training with the Westchester Players, but it was not long until his Broadway debut in support of Lionel Barrymore in The Copperhead at the Shubert Theatre in 1918. The 17-year-old Morris played a 35-year-old in the play. By the mid-1920s he was under the personal management of George M. Cohan and appeared in three plays for the Broadway legend between 1926-1928, The Home-Towners, Yellow and Whispering Friends. His biggest hit of the period was said to be the Shipman-Hymer underworld melodrama Crime which saw Morris and Kay Johnson support James Rennie.

In November 1928 he and Regis Toomey were among five Broadway players selected by director Roland West to appear in his adaptation of Broadway’s Nightstick, soon retitled Alibi for the screen. The film catapulted Chester Morris to fame and secured him his only Academy Award nomination for Best Actor (He lost to Warner Baxter). It also forged a friendship and working relationship with West, who Morris would star for in two additional films.

In November 1928 he and Regis Toomey were among five Broadway players selected by director Roland West to appear in his adaptation of Broadway’s Nightstick, soon retitled Alibi for the screen. The film catapulted Chester Morris to fame and secured him his only Academy Award nomination for Best Actor (He lost to Warner Baxter). It also forged a friendship and working relationship with West, who Morris would star for in two additional films.

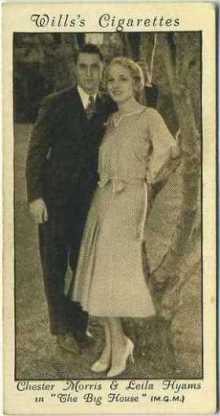

Alibi immediately established Morris as a star and he continued to impress throughout 1930 when parts included his playing a Russian escaped from a German prison camp in The Case of Sergeant Grischa, a lost film; As Norma Shearer’s unfaithful husband in The Divorcee, a role that won Shearer her Academy Award in a film that is now considered a pre-Code classic; Starring behind bars in groundbreaking prison flick The Big House, which won a couple of Academy Awards itself; Back with Roland West in old dark house mystery The Bat Whispers, a talkie remake of the director’s earlier The Bat (1926); Morris was a Wall Street financier turned pirate on the high seas in West’s final film, Corsair, in 1931; 1932 saw Morris succumb to Jean Harlow’s charms in another classic of the era, Red Headed Woman; He’s also very good that year opposite Sylvia Sidney in a talkie remake of The Miracle Man, which sees character actor John Wray twist himself into the part originally played by Lon Chaney in 1919; We have previously looked at his gum-chewing, cigarette-smoking gangster opposite Joan Blondell in Blondie Johnson (1933) and gave brief mention to King for a Night (1933) in another past post.

After his second movie for West, The Bat Whispers, Morris had a shot at what would have been a career defining role, though one which could have typecast him in a genre that may have cost him some of those plum roles that followed. West himself either cursed or (more likely) saved his friend when a producer from Universal wrote asking if it would be possible for Chester Morris to play Dracula in their coming production. West replied, “Don’t think I’d care for that part for Chester as we are looking for romance” (Donati 60). While the idea of Chester Morris as Dracula is intriguing I think I’m happier that in the end Morris wound up playing parts more reminiscent of Cagney than Lugosi from 1930 onwards.

After his second movie for West, The Bat Whispers, Morris had a shot at what would have been a career defining role, though one which could have typecast him in a genre that may have cost him some of those plum roles that followed. West himself either cursed or (more likely) saved his friend when a producer from Universal wrote asking if it would be possible for Chester Morris to play Dracula in their coming production. West replied, “Don’t think I’d care for that part for Chester as we are looking for romance” (Donati 60). While the idea of Chester Morris as Dracula is intriguing I think I’m happier that in the end Morris wound up playing parts more reminiscent of Cagney than Lugosi from 1930 onwards.

Above: Lionel Barrymore and Chester Morris on the set of Public Hero #1. Morris had made his Broadway debut with Barrymore in The Copperhead back in 1918.

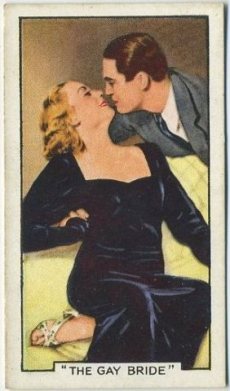

Between enforcement of the Production Code and the onset of Morris’ years as Boston Blackie, he starred in several interesting films, though not as many gems as he had previously appeared in. Among those I’m familiar with comes a part opposite Carole Lombard as boss Nat Pendleton’s underling in crime comedy The Gay Bride (1934); Chester going undercover in the entertaining Public Hero #1 (1935) with Jean Arthur and Joseph Calleia as unlikely siblings; As one of the Three Godfathers along with Lewis Stone and Walter Brennan in the 1936 version of the film better remembered in its next incarnation from John Ford in 1948; Morris gets mixed up with Fay Wray in Alf Green’s They Met in a Taxi (1936); Richard Dix competes with Morris for young Joan Fontaine in Lew Landers’ Sky Giant (1938); Ralph Bellamy tries to get to the bottom of what makes psycho-Chester tick in Blind Alley; Morris is stranded in the jungle with passengers including Lucille Ball in Five Came Back (1939), one of his more popular and better known “B” efforts thanks to Lucy’s presence.

Boston Blackie began as a Jack Boyle story in the American Magazine in 1914. Boyle wrote additional Blackie stories and the character was eventually adapted to the silent screen. He’d been out of circulation since the late 1920s when Columbia rebooted it as their latest crime series with 1941’s Meet Boston Blackie starring Morris. The fourteen Blackie films were largely lighthearted crime stories that saw Morris’ Blackie, a reformed criminal, along with sidekick Runt (usually George E. Stone) implicated in some crime by Inspector Faraday (Richard Lane) and working to clear his name, often with an assist from millionaire pal Arthur Manleder (usually Lloyd Corrigan). The series had a very similar template and tone to Columbia’s Lone Wolf series. Fun and breezy, you don’t have to think too hard during any Boston Blackie entry. Most of the enjoyment comes from the interaction of the likable recurring characters. Here’s a brief look at Confessions of Boston Blackie (1941) from a past post.

Boston Blackie began as a Jack Boyle story in the American Magazine in 1914. Boyle wrote additional Blackie stories and the character was eventually adapted to the silent screen. He’d been out of circulation since the late 1920s when Columbia rebooted it as their latest crime series with 1941’s Meet Boston Blackie starring Morris. The fourteen Blackie films were largely lighthearted crime stories that saw Morris’ Blackie, a reformed criminal, along with sidekick Runt (usually George E. Stone) implicated in some crime by Inspector Faraday (Richard Lane) and working to clear his name, often with an assist from millionaire pal Arthur Manleder (usually Lloyd Corrigan). The series had a very similar template and tone to Columbia’s Lone Wolf series. Fun and breezy, you don’t have to think too hard during any Boston Blackie entry. Most of the enjoyment comes from the interaction of the likable recurring characters. Here’s a brief look at Confessions of Boston Blackie (1941) from a past post.

Morris starred in all fourteen Boston Blackie films in addition to playing the part on the radio in 1944. During the war years Morris also kept busy entertaining the troops in hundreds of shows for the U.S.O. His specialty was magic tricks, a passion since his boyhood. He is said to have entertained the troops in hundreds of shows during this period, with approximately 380 performances the number reported in his obituaries. He also managed to peeve the magic community with a 1947 Popular Mechanics article that exposed some tricks of the trade.

Morris starred in all fourteen Boston Blackie films in addition to playing the part on the radio in 1944. During the war years Morris also kept busy entertaining the troops in hundreds of shows for the U.S.O. His specialty was magic tricks, a passion since his boyhood. He is said to have entertained the troops in hundreds of shows during this period, with approximately 380 performances the number reported in his obituaries. He also managed to peeve the magic community with a 1947 Popular Mechanics article that exposed some tricks of the trade.

Like many of his peers Morris did a great deal of television work throughout the 1950s when he appeared in several episodes of the various anthology series that were popular at the time: Schlitz Playhouse, Lux Video Theatre, Suspense, Omnibus, Studio One, Playhouse 90, etc. He had a recurring role as a detective in the 1960 series Suspense: Danger and also made guest appearances throughout that decade on shows such as Rawhide, Naked City, Ben Casey, Route 66, Doctor Kildare, The Defenders and others.

“I’m ham enough to love to watch the replays of my old movies on television.” – More from Morris in 1958.

Morris also went back to live theater during those last couple of decades of his life. He appeared with the touring company of Detective Story in the early ‘50s and made it back to Broadway for Joshua Logan’s Blue Denim in 1958 and then the political thriller Advise and Consent, based on the popular Allen Drury novel, in 1960. He had been appearing as Captain Queeg in The Caine Mutiny Court Martial at the Bucks County Playhouse in New Hope, Pennsylvania when on September 11, 1970 he was found dead in his hotel room. He was ill with cancer at the time, but his death was reported to be from an overdose of barbiturates. The Bucks County coroner was unable to tell if the actor had taken his own life or if his death was accidental.

Morris also went back to live theater during those last couple of decades of his life. He appeared with the touring company of Detective Story in the early ‘50s and made it back to Broadway for Joshua Logan’s Blue Denim in 1958 and then the political thriller Advise and Consent, based on the popular Allen Drury novel, in 1960. He had been appearing as Captain Queeg in The Caine Mutiny Court Martial at the Bucks County Playhouse in New Hope, Pennsylvania when on September 11, 1970 he was found dead in his hotel room. He was ill with cancer at the time, but his death was reported to be from an overdose of barbiturates. The Bucks County coroner was unable to tell if the actor had taken his own life or if his death was accidental.

Chester Morris was married twice and had three children, a son and a daughter by first wife, Suzanne Kilbourne, to whom he was married from 1926 through 1940. Just days after his divorce was finalized Morris married socialite Lillian Kenton Barker, a former Powers model and the original Chesterfield girl. They had one son.

Chester Morris was 69 years old. Shortly after his death the public saw him playing a fight promoter in his final film appearance with the release of The Great White Hope (1970) starring James Earl Jones in October 1970.

Cited

- Donati, William. The Life and Death of Thelma Todd

. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012.

Thanks, Cliff! My goal is now to get my hands on the BOSTON BLACKIE radio show.

Love the info about his entertaining the troops.

Fantastic photos, too!!!!

Best wishes,

Laura

Thanks so much, Laura, I know he’s a favorite of yours! I think I needed all of the movies TCM played with him today, so I’ll be excited to check out my DVR later.

There were at least three playing today I didn’t have so I’m excited to have a new supply of Chester movies to watch in addition to my ongoing viewing of the BOSTON BLACKIE movies!

Best wishes,

Laura

Laura, I actually don’t think I’ve seen any of the Chester Morris that TCM played on Wednesday. Of course, I began my viewing with the 1930 flick starring Alice White, Playing Around, but looking forward to the Dix-Morris title now!

Thanks for all the swell info on my new “crush”. I have to get caught up on these films.

Hah ha, enjoy @loveless — sorry if I scare you off your new crush any with that last pic: That mustache rivals Cagney’s of the same period for pure cheesiness 🙂 Enjoy the movies, I know I will!

Morris really was a talented and versatile actor. I’m impressed by his ability to move between nice-guy and villain roles (he’s especially memorable playing a nasty bandit in the ’36 version of Three Godfathers). His leading-man career at MGM seemed to have petered out after the ascent of Clark Gable, leaving him to specialize in character roles. My sense about Morris is that he was an actor’s actor, and playing character roles suited him fine – you can see his range in Boston Blackie, in which he did a number of impersonations (elderly gents and even women).

Shoot, I forgot to mention his Boston Blackie disguises, I love when he does the old man. It’s a shame MGM didn’t run with him, he could have been their Cagney–not that he’s that good, but he could have definitely pulled off more tough guy parts. Like my previous subject, Richard Dix, he comes naturally equipped with jagged facial features that make him very believable as a tough or even a he-man type. I envy their respective jawlines! And the fact that they both look like rough guys also enhanced their less threatening roles. Thanks for the comment, GOM!

Chester Morris is one of my favourite actors and you have done him proud with

your piece. Just last week we watched “Blind Alley” and he must have been

thrilled to be able to sink his teeth into a really meaty “baddie” role. Another

one I like is “I Promise to Pay” – just a B but he made his role really special.

Interesting to read about “Dracula” – “The Bat Whispers” he did play a very

sinister character but I really liked the way he came out at the end and

asked the audience not to reveal the ending. I think he had just way too much

humour to play “Dracula” – I could imagine him cracking up, I suppose because

he always seemed a likable player.

“Alibi” – I thought he really should have won the Academy Award for his role

(I also think Bessie Love should have won the Best Actress as well). I think

his performance still holds up really strongly today, Regis Toomey, I think the

“happy drunk” act is just kept up too long!! Must watch it again soon.

I agree, it was pretty neat the way he comes out at the end of The Bat Whispers though, unfortunately, that’s my favorite part of the movie. I hope I have a copy of I Promise to Pay, sounds good and I like Helen Mack in about anything. Yep, Regis Toomey was a bit much.

Here is the Facebook page for the new book on Chester Morris being written by me and my wife: https://www.facebook.com/ChesterMorrisBook/

Great, Scott, thanks so much for sharing! Congratulations on this, a worthy subject!