I might be waiting for one more package to arrive (c’mon, UPS!) but my Christmas shopping has been all done for a few days now. It’s been several years since I’ve dared to shop in person, though I try to have a good time online and bought more from my peers (eBay/Etsy sellers) than ever before this Christmas season. The mall in my neck-of-the-woods has been a bit upscale for my tastes for a few redesigns now, so the online boutique seller is about the only way I can recapture a little of the magic I enjoyed most back when I did actually venture out in December.

You can’t beat Christmas for most retailers. In addition to the extra dollars earned come the holiday season, there’s that kick, a bit of an adrenaline high, that comes from the increased volume and pace of the sales. I just caught The Shop Around the Corner again on TCM Sunday night. I loved that Frank Morgan couldn’t bear to be away from his shop on Christmas Eve. Against doctor’s orders he returned to the floor and the buzz of activity, an energy that can be measured at the end of the day simply by counting the receipts.

One of my favorite classic movie settings is the business world, be it big business or the local five and dime. I especially get a kick out of seeing the old products and hearing the pocket-change prices called out in a retail setting. I’ve never owned a shop myself, though my current online business has its roots in trade shows. That was a world of handshakes and familiar faces, wheeling and dealing with cash exchanged across a table. The setting, a transient one, more resembled an ancient Roman bazaar than it did any store inside that mall I referenced above.

The Christmas counter frenzy is at a peak during a scene in one of my more recent favorites of the retail world, Sweepings (1933). Sweepings is not a Christmas movie. The original 1926 novel by Lester Cohen (1901-1963) and the two RKO adaptations that followed in the 1930s are about the Pardway family, especially the legacy Daniel builds for his children and his disappointment as they grow up to leave little doubt that they will never measure up to his lofty expectations. Spoiled from youth they, in fact, fail to live up to even normal societal standards.

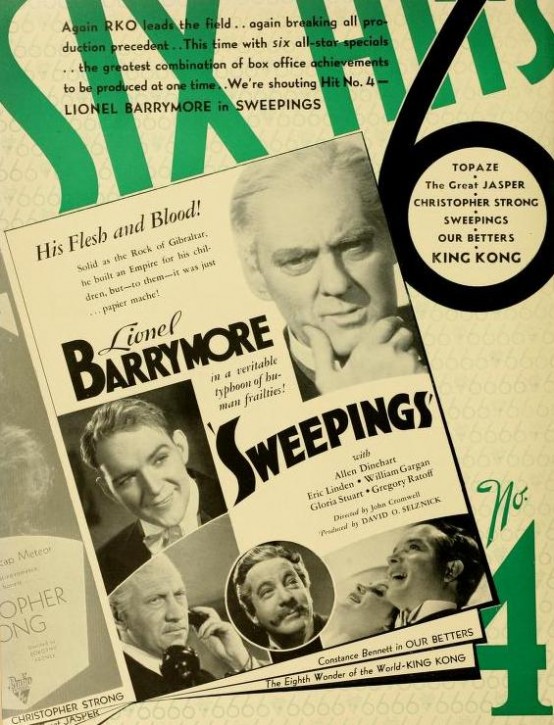

In 1933 RKO hired Cohen to adapt his own novel for the screen. With RKO he would also work on the script for One Man’s Journey (1933), which like Sweepings starred Lionel Barrymore, before handling the 1934 adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage. That latter title was also directed by Sweepings’ John Cromwell and featured Bette Davis’ breakout screen performance. The earlier Sweepings was in the same production cycle as King Kong at RKO and thus shared a good deal of the more sensational Kong’s publicity from filming through release.

Full-page trade ad in Hollywood Reporter, February 10, 1933. Note King Kong among the other 6 big RKO movies coming soon.

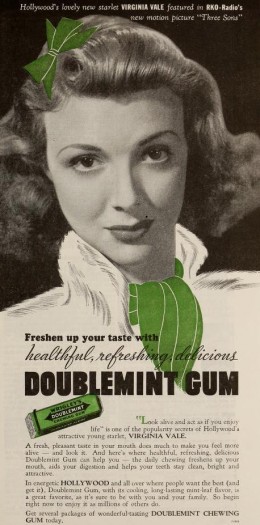

Not surprisingly the 1933 adaptation of Sweepings sticks close to the author’s original novel, trimming sections from the beginning and the end, but retaining a toned down version of much of the detail found throughout the original text. A 1939 remake, Three Sons, adapted by John Twist and directed by Jack Hively, features a strong performance by star Edward Ellis, but is otherwise pretty colorless. Understandably the script veers further away from the original and the finished film seems more an excuse to celebrate Jesse Lasky’s two “Gateway to Hollywood” contest winners, Virginia Vale and Robert Stanton, than anything else.

This 1939 Doublemint Gum ad was part of the Virginia Vale push in the wake of the “Gateway to Hollywood” contest.

Daniel raises his empire from the ashes of the Chicago fire, building a legacy that his children want no part of beyond cash handouts from their father. They rebel one at a time until the final indignation of the youngest Pardway, Freddie, long his father’s pride and joy, smashing Daniel’s last hopes by revealing himself as not only adverse to work but also as the worst type of cad.

While the overall atmosphere of the 1939 movie feels far removed from the 1933 original, when it comes to the details the films actually only differ in a few small ways. In every case the 1933 Cohen adaptation sticks closer to his original novel, but that earlier film also benefits from a more experienced and, in most cases, more talented supporting cast. William Gargan provides a fun casting twist in appearing as eldest son Gene in the earlier movie and then returning to play Gene’s uncle, Thane, in the remake (Played by Alan Dinehart in the original).

One of the more fascinating characters in Cohen’s novel is Mamie Donahue, the shop girl we witness youngest son Freddie seduce in each movie adaptation. In the 1933 film, Sweepings, Mamie is played by young Helen Mack (pre-Son of Kong even), and she’s a sensation in the part, making you wish for more (and you get it in the book). As in Cohen’s novel Mack’s key scene, in which Mamie meets Freddie, is set on the floor of Pardway’s Bazaar during the Christmas Eve rush.

“Wuzza matter, girlie?” Freddie asks the worn-out girl in the novel.

The floor of the Bazaar is packed with people on Christmas Eve. In the prior scene Barrymore’s Daniel paged through the paper with Freddie (Eric Linden), proudly showing off pages and pages of Bazaar sales ads for Christmas Eve. Cohen details the frantic sales schedule more precisely in his novel:

At seven o’clock of that night the gaudy wares of the Main Floor and of Toytown were to be sold at slightly above cost. At eight o’clock everything was to go at cost. An hour later prices were slashed to slightly below cost. What Main Floor and Third Floor merchandise remained after that was to be sold at almost any price.

Freddie enters the Bazaar shortly after store manager Abe Ullman (Gregory Ratoff) has scolded a salesgirl for not lowering prices below cost. He spots Mamie at the gift wrapping counter and makes a beeline towards her.

William B. Waits, in his history The Modern Christmas in America, writes that this was typically a high stress seasonal job held by a woman or young person or, like Mamie Donahue, someone who fit both ends of the description. This type of holiday worker became a seasonal cause for the muckraking journalists who were prominent during the period in which this scene of Sweepings was set, about 1910. Waits discovers that writers of the period found the poor treatment of these workers, specifically “low pay, long hours, and poor working environments” (183) against the spirit of Christmas. Beyond the general labor laws that followed were reforms aimed at making the current situation better, such as the Shop Early Campaign, which helped spread out the Christmas shopping season, and the Society for the Prevention of Useless Giving, which aimed to eliminate the almost “compulsory gift giving” of the period (185).

In Sweepings Mamie is astounded by Freddie Pardway’s casual interruption of her toil and it touches off a breakdown that Cohen shows just as effectively in his book as Helen Mack does on screen. He writes:

In Sweepings Mamie is astounded by Freddie Pardway’s casual interruption of her toil and it touches off a breakdown that Cohen shows just as effectively in his book as Helen Mack does on screen. He writes:

“What was the matter? She’d tell him what was the matter. She tried, but the words would not leap over her sobs. Her bones ached. Her body felt as if it were falling apart. A terrible resentment, like a running sore, was discharging within her heart. What was the madder? The madder! She heard herself scream” (245-246).

Mamie loses control and is shown in each movie tossing packages and wrapping materials at the customers before she faints. She comes to in the back of a taxi riding with Freddie Pardway.

Cohen describes Freddie’s come-on to Mamie as shown in the 1933 film, but adds Mamie’s thoughts to his telling. She “became the exalted as his fingers felt over her flesh and fed the fires of her revolt. The love hunger in her was being appeased. Here, at last, was one beside her who dared drink of that which others had just dared to desire” (248).

She gives in to her desires. It’s a steamy scene in the 1933 movie with Linden moving his hands around Mack’s throat and down the top buttons of her shirt as he whispers that it “May never be like this again.” He then puts his class ring on her finger and twists it around to hide its insignia, adding in a heavy whisper, “Just like-this.” They kiss. As hot as this plays in the movie, the book provides a reason beyond any symbolism for Freddie’s screwing the ring around Mamie’s finger: It will look like a wedding band to the hotel clerk.

Mack: “You know, you’re the first guy that was ever nice to me.” His hands move over her. “You think that’s nice?”

While the movie fades to the next scene, the novel tells us that Freddie left Mamie in a hotel the next morning with a hundred dollar bill as her reward. The reward becomes her downfall. “Why, I never seen a hundred bucks!” she later explains to Daniel. “And I was such an innocent fool, mister, I thought I’d get a hundred bucks every night. So I went on the turf, see?” (278). Both movies skip that bit, but each shows her being bought off by Daniel Pardway. After Daniel writes her a check, Mamie disappears from the screen.

In the novel Mamie takes takes the handful of bills that Daniel offers her, but her temper winds up ruining any bigger payoff. Her character returns later in the book and we’re treated to her rise from the “six-fifty per” she used to make each week in the Bazaar as her story outlasts even the Daniel Pardway character.

Helen Mack, as the Mamie of Sweepings, really brought this character to life and provided a believable template for Mamie’s later adventures, which I only read after first seeing the movie. Mack’s outrage over being had by Freddie and her anger over her general lot in life as well as her vindictiveness when given the opportunity to cash out, made it impossible for the actress not to invade my reading of Cohen’s novel and enhance his original creation.

Forget Three Sons as it tones down too many elements of Sweepings and is filled with underwhelming performances (One major exception, Edward Ellis, whose Daniel Pardway I actually preferred to that of Lionel Barrymore’s in the original).

Both movies effectively show Daniel Pardway’s success in business and failure in family, with major differences coming mainly between the relationship between Daniel and his general manager, Abe Ullman.

The scenes that Barrymore’s Daniel shares with Gregory Ratoff’s Abe closely resemble what transpires in the novel. Cohen translates much of his original intention to the screen. But in the later movie Edward Ellis’ Daniel is a much softer touch with J. Edward Bromberg’s Abe, who along with the youngest Pardway boy come together to make for an overall happier ending. Neither movie fully captures the complicated feelings that Cohen’s original Daniel Pardway had for Abe. Right or wrong Daniel considers Abe a turncoat, but he also realizes that Abe has become the greatest hope for his continued legacy, through the Bazaar, after his own death.

Gregory Ratoff’s Abe talks business with Lionel Barrymore’s Daniel Pardway. Daniel’s brother Thane (Alan Dinehart) stands between them.

Cohen’s novel is highly recommended for fans of either movie as it provides much more to the Pardway story. It take fifty-seven pages before the novel reaches the opening of the movie, Daniel’s arrival in Chicago, with a prehistory tracing the Pardway family to the American Revolution and describing Thane and Daniel’s boyhood and youthful adventures. Where the movies end, the novel continues with an additional section titled “The Alien Conqueror,” all about Abe Ullman. It also reveals what happens to the Pardway children and, most importantly, Mamie Donahue, who really could have been the focal point of an entirely different movie in a later era.

Edward Ellis is Daniel Pardway in Three Sons. William Gargan stands at his left. Gargan played Daniel’s oldest son, Gene, in Sweepings, but returns to play Daniel’s brother, Thane, in Three Sons.

The book is also more lurid than even the pre-Code version of the movie with more sex, though tastefully described, as well as surprising accounts of drug use and addiction. Almost all of Cohen’s characters are better brought to life on the page with one, Daniel’s second wife, not even appearing in either movie. The book is tops, but the 1933 movie is very good. Most will want to skip the 1939 remake.

I watched both Sweepings and Three Sons on Turner Classic Movies. Sweepings can also be purchased as a Made-to-Order DVD-R from WarnerArchive. Three Sons is not yet available on home video.

Cited

- Cohen, Lester. Sweepings

. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1928.

- Waits, William B. The Modern Christmas in America: A Cultural History of Gift Giving

. New York: New York University Press, 1993.

Well, I’m glad you did a review of a movie that Helen Mack is in. I am a huge fan of Helen’s (see my website dedicated to her at http://www.helenmack.us). Because of this movie, I suspect she caught the attention of a few people. I’ll have to order the movie as it wasn’t in print a few years back. Unfortunately most of her starring roles were in rather poorly written movies. There are some exceptions, but for the most part, she never got a good chance to showcase all her talents.

Hi Daryl,

Great to hear from you. I’m a long-time fan of your site … I think we did a link exchange about a decade ago 😉

Helen’s part here is small, but I think you can tell that she really won me over! After you catch the movie I definitely recommend grabbing a copy of the book because her character’s story extends well beyond what is shown in the movie (got mine for under $10 at Amazon). As mentioned above, after watching the movie, Helen totally invaded my reading of the novel. She fit the part very well!

I’m hoping to write about something else with Helen in the New Year. I’ve been meaning to cover Girls of the Road for a long time now, though The Return of Peter Grimm looms as a possibility as well.

Thanks for taking the time to comment and Happy New Year —

Cliff

PS: Just updated my first mention of Helen Mack in this post with a link over too.