I only mentioned Harry Reichenbach once when writing about The Half Naked Truth, but all it takes to want to learn more about this real life figure is a snippet of text following any comma after his name.

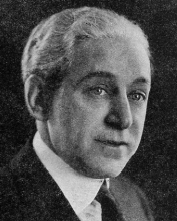

Harry Reichenbach was the “Father of Ballyhoo” whom the Jimmy Bates character played by Lee Tracy in The Half Naked Truth is based upon.

Harry Reichenbach was the “Father of Ballyhoo” whom the Jimmy Bates character played by Lee Tracy in The Half Naked Truth is based upon.

Reichenbach was one of those characters of the early 20th Century whose real life exploits were so colorful that history calls him up every so often and leaves us little more than legend. The stories are so over the top that I don’t even know how much of them are true. They certainly qualify as oft-repeated.

In case you haven’t seen it I won’t explain exactly what happens in The Half Naked Truth, but I’ll begin by describing two of Harry Reichenbach’s most famous bits of ballyhoo which certainly played a part when Gregory La Cava and Corey Ford wrote the script for the 1932 film.

In 1920 one Thomas R. Zann called for a reservation at New York’s Hotel Bellclaire. When Mr. Zann asked if the hotel had any problems with his bringing a pet along he was told, “None in the world” (”Feline Pet”). Zann arrived with a moving van out of which came a large crate that onlookers suspected must have contained a piano. The crate was dragged from the van and raised through the Bellclaire’s windows from outside by a system of pulleys.

Later in the day, after Mr. Zann had settled into his room, he phoned room service and ordered fifteen pounds of raw and lean beefsteak. The hotel manager got on the phone to confirm the strange request and soon accompanied a waiter to deliver the steaks to suite 117. “A roar, deep mouthed and anticipatory greeted them.” And then supposedly all hell broke loose as the men came face to face with Mr. Zann’s pet lion.

The original 1920 reportage concludes with the mention that “It occurred to the desk sergeant that this might be some one trying to put over a deep laid press agent scheme and trying to get the police to help put it over. He suggested as much, but later Zann strenuously denied that he had ever so much as heard of press agent stuff” (”Feline Pet”).

It turns out the desk sergeant was on the right track, though he apparently didn’t notice the connection between Mr. Thomas R. Zann, or T.R. Zan for short, and the new Goldwyn distributed film, The Revenge of Tarzan (1920).

Another time a half dozen or so Turkish men checked into another of New York’s top hotels (the Plaza in one telling) and turned all press away. At first.

They finally let it be known that they were searching for a kidnapped Turkish maid known back home as “the virgin of Stamboul.” They offered a $20,000 reward for information leading to the virgin. The moment the newspapers picked up the story Universal’s The Virgin of Stamboul (1920) was put into release (Swan).

Over the years this pair of stories have come to more closely resemble the action shown in The Half Naked Truth, so I’ve chosen to share versions told in earlier days. The Tarzan story as told above is from a 1920 period syndicated newspaper report. The story about The Virgin of Stamboul comes from a Gilbert Swan article published just a few weeks after Reichenbach’s death in 1931. Later tellings also put the virgin in the room and more closely resemble the story of Lupe Velez' Princess Exotica character from the film.Harry Reichenbach was born in Maryland in 1882. He was uneducated yet claimed to be fluent in six foreign languages. He started small, as amusement manager of Island Park. He left Maryland in about 1905 and was soon working as manager of magician the Great Raymond whom he took on a world tour. That partnership ended in 1909 when Reichenbach landed a job managing a summer stock theater at Hartford, Connecticut for David Belasco (”A Cumberland”).

His obituaries claimed that besides Belasco he also worked for the Schuberts, Klaw and Erlanger and William Fox.

He was personal press agent at one time or another for Gloria Swanson, Wallace Reid, Thomas Meighan, Ethel Barrymore, Charlie Chaplin and Pola Negri. His obits credited Reichenbach as discoverer of Douglas Fairbanks, Marguerite Clark and Clara Kimball Young and said he made Barbara La Marr and Francis X. Bushman popular.

One story tells about a bit of Reichenbach trickery used to secure Bushman a new contract with a significant pay hike.

Reichenbach stuffed his pockets with twenty dollars in pennies when he and the actor arrived in New York at Grand Central Station. On the walk to Metro Studios Reichenbach let the pennies drop to the sidewalk where they were collected by children. After a time a crowd grew simply out of curiosity. Supposedly when Reichenbach and Bushman reached Metro they were followed by such a large entourage that it was taken as an unexpected sign of the actor’s popularity.

Reichenbach stuffed his pockets with twenty dollars in pennies when he and the actor arrived in New York at Grand Central Station. On the walk to Metro Studios Reichenbach let the pennies drop to the sidewalk where they were collected by children. After a time a crowd grew simply out of curiosity. Supposedly when Reichenbach and Bushman reached Metro they were followed by such a large entourage that it was taken as an unexpected sign of the actor’s popularity.

Bushman had been making $250 per week. Metro snatched him up at $1,000 per week under the new deal and thought they had a bargain (Orrock).

When Francis X. Bushman returned to film in 1951 he told Hollywood columnist Erskine Johnson a story about one of Reichenbach’s stunts on his behalf:

“I was to open the state fair and I had made reservations at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco. But something came up and I put off the trip for a day. Suddenly the telephone rang. It was the chief of police in San Francisco.

“They had found a real bomb in the room reserved for me at the St. Francis. And with it there was a note from a woman named Mildred. It said, ‘If I can’t have you, Francis, no other woman will.’

“Next day when I arrived in San Francisco the town was wild. The news about the bomb had been flashed around the world. Headlines everywhere.

“When I drove to the fair grounds there were 25,000 people outside the gates. They couldn’t get in. I broke the record of three United States Presidents and Billy Sunday” (Johnson).

Bushman said he didn’t even realize it was a publicity stunt at first. He wouldn’t have thought even Reichenbach would use a real bomb for press! A few weeks later Bushman received a call from the San Francisco chief of police who told them the whole thing was a hoax and that Reichenbach would get locked up for life if he ever showed up in San Francisco again.

Away from the screen world Reichenbach’s most famous bit of exploit appears to have been the furor he raised over September Morn. This seems to have been pretty well debunked at the Museum of Hoaxes website, but the Reichenbach legend is not complete without its retelling.

Matinee de Septembre was painted by Paul Chabas in 1912. It depicted a nude woman standing ankle deep in water, presumably on a September morn.

Matinee de Septembre was painted by Paul Chabas in 1912. It depicted a nude woman standing ankle deep in water, presumably on a September morn.

A small New York art shop had 2,000 September Morn prints in stock and they weren’t selling. Not even at 10¢ apiece. Reichenbach saw opportunity.

He told the owner of the shop to put one of the prints in his window and that he’d sell out his entire stock within a month. Once the image was on display Reichenbach began a campaign of complaints aimed at Anti-Vice Society head Anthony Comstock.

The outraged Reichenbach finally managed to get Comstock to accompany him to see the lewd painting. When they reached the shop there was a group of young boys leering at the image in the window. Comstock was outraged and eventually took the matter up in the courts. Comstock was unsuccessful, but Reichenbach, who had hired those leering boys himself, cleaned up.

The 2,000 prints which wouldn’t sell for a dime were soon gone—at a dollar apiece. In all seven million copies of September Morn sold at that price and in our story it was all thanks to the publicity Reichenbach had generated.

Reichenbach was just 49 years old when he died July 4, 1931. He hadn’t been active for eight months prior to his death, his ailment having, in his own words, “jerked me out of the picture” (”Theatrical World”).

It was a couple of years after the death of Harry Reichenbach, early in 1933 as The Half Naked Truth played in theaters, when columnist O.O. McIntyre gave a concise history of Reichenbach’s profession to that time:

“Pressagentry has gone through many refinings since Toby Hamilton’s silk hat and circusey alliterations. The next school was sponsored by Harry Reichenbach, a little more subdued, but still blatant. After him, came the Ivy Lees, with frock coats and in diplomatic comity, styling themselves counsels of public relations. The person who has tamed press agent exaggerations more than any other is Marlen E. Pew, whose trade journal of newspapering exposes such buncombe to editors.”

Some other bits of ballyhoo I found attributed to Harry Reichenbach:

“I went through Italy doing press work for President Wilson … and I made them bow down and pray to him before they did to the saints,” said Reichenbach himself to New York’s district attorney during a 1920 investigation into fake publicity (”A Cruel”).

The same article also credits Reichenbach for being behind:

“Having the Hudson river dragged in search of May Yohe, the actress, while she was in hiding ready to appear at the theater to greet an extra sized crowd drawn by publicity.”

“Of having a large picture of a matinee idol stolen from in front of a theater and finding it in a girl’s school where he had planted it.”

“And of conceiving a plan, which he said was to be aided from the White House, of having Clara Kimball Young kidnapped by Mexican bandits and rescued by ‘eight blond cavalrymen.’”

“And of conceiving a plan, which he said was to be aided from the White House, of having Clara Kimball Young kidnapped by Mexican bandits and rescued by ‘eight blond cavalrymen.’”

More second and third hand reports of Reichenbach coming long after the fact:

He “once caused the overthrow of a South American government with a coupon-ad campaign that fired up the country’s citizens” (Orrock).

Gave an expensive ham sandwich at Reuben’s Delicatessen the necessary push that resulted in the famed Rueben’s Sandwich coming to popularity (Pegler).

From Leonard Lyons:

“He lost a British film account when he proposed to advertise a movie by using a magic-lantern and get himself arrested by throwing the ad onto the walls of Buckingham Palace.”

Also from Lyons: “He made Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks a bestseller by flooding the small-town postmasters with letters asking that the book be barred from the mails.”

From one obituary: “Then there was the elephant that swam ashore at Coney Island one summer evening. ‘Toto’ was Mr. Reichenback’s elephant.”

And finally, calling The Half Naked Truth’s Ella Beebee to mind: Winning a $50 bet when he claimed he could take an unknown sewing machine girl and turn her into a vaudeville headliner at the Palace within ten days.

True, false, in between, I don’t know. The stories about the lion and the virgin certainly seem to have evolved over time from the clippings I read. I wanted to believe September Morn, but it did smell a little fishy. I’m left feeling a little bit like Frank Morgan’s Merle Farrell in The Half Naked Truth: “Course, I knew all along that she wasn’t a princess.”

Harry Reichenbach’s autobiography Phantom Fame was published in the year of his death, 1931. Phantom Fame would also be the working title of the film The Half Naked Truth while in production. The movie was released at the end of 1932 and from that time well into 1933 it gave Harry Reichenbach his own last great round of publicity.

Sources

- “A Cruel Hoax.” Manitowoc Herald News 5 Aug 1920: 5. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- “A Cumberland Boy.” Evening Times Cumberland Maryland. 30 Mar 1910: 3. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- “Feline Pet Accustomed to Best Hostleries and Bred, Owner Says.” Oakland Tribune 6 Jun 1920: 18. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- “Greatest of Press Agents Is Dead.” Decatur Daily Review 5 Jul 1931: 18. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- Heimer, Mel. “My New York.” Daily Review. 2 Nov 1972: 29. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- Johnson, Erskine. “Bushman Back in Movies.” Rhinelander Daily News 5 Oct 1951: 4. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- Lyons, Leonard. “The Lyon’s Den.” Amarillo Daily News 10 Sep 1948: 22. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- McIntyre, O.O. “New York Day by Day.” Piqua Daily Call 3 mar 1933: 4. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- “Native of This County Lives Again in Movies.” Cumberland Times 5 Feb 1933: 6. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- Orrock, Ray. “Harry and the Naked Lady.” Daily Review 23 Sep 1975: 20. NewspaperArchive 18 Sep 2012.

- Pegler, Westbrook. “Early days of Gotham Recalled.” Lima News 4 Jan 1958: 4. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

- “Theatrical World Mourns Death of Noted Character.” Charleston Gazette 4 Jul 1931: 1. NewspaperArchive. Web. 18 Sep 2012.

I’ve been looking for a copy of Phantom Fame to no avail. This article is the next best thing. Thank you!