Talk about bad timing. The Wolf Man was released five days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The press viewed it a few days earlier at a December 9 Universal preview, and like most horror films the immediate critical reception was typically either savage—especially given the poor timing—or mocking.

Talk about bad timing. The Wolf Man was released five days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The press viewed it a few days earlier at a December 9 Universal preview, and like most horror films the immediate critical reception was typically either savage—especially given the poor timing—or mocking.

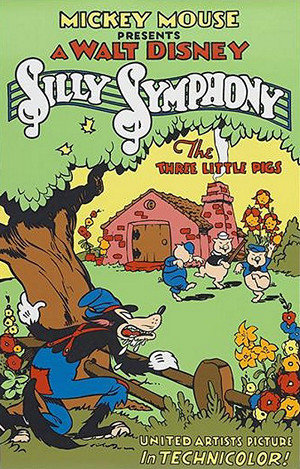

Variety called The Wolf Man “dubious entertainment at this particular time.” Theodore Strauss of the New York Times wrote that the monster “looks a lot less terrifying and not nearly as funny as Mr. Disney’s big, bad wolf.” To many, The Wolf Man was a silly little genre film most notable for wasting a deep and respected cast of stars.

Within a few months the silly little genre film pulled in over a million dollars at the box office (Weaver). By 1997, it was so ingrained within American culture that it was honored with an appearance on a postage stamp. Every few years a new werewolf movie comes along, but usually they just confirm how much The Wolf Man deserves its exalted status.

Built on the foundation of Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Mummy, Universal’s second wave of horror releases, beginning with Son of Frankenstein in 1939, was largely composed of sequels and retreads. The Wolf Man provides a major exception, the original proving so successful that its monster was soon stalking the dark alongside the studio’s more established creatures of the night. After Dracula and Frankenstein (both 1931), Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff appeared in several genre classics throughout the decade, but by 1941, Universal limited Lugosi to supporting roles, and Karloff was finding new success on the stage. Before Lugosi and Karloff, Universal had had Lon Chaney, famed star of silent classics such as The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Chaney’s death in 1930 opened the door for Lugosi and then Karloff to don capes and collodion while taking up the late master’s mantle at the box office throughout the 1930s. With horror relevant again in the new decade, a new star was finally smelling some success after several years of toil.

The Wolf Man breathed fresh life into Universal’s horror cycle throughout the 1940s. Its success reached beyond Universal and quickly inspired titles such as The Undying Monster (1942) at Twentieth Century Fox and Cat People (1942) at RKO. But it was the unique talent under Jack Pierce’s Wolf Man makeup who emerged as one of the most important horror movie actors of all-time.

He had appeared in over fifty films by the time his Lennie Small touched moviegoers hearts in Of Mice and Men.

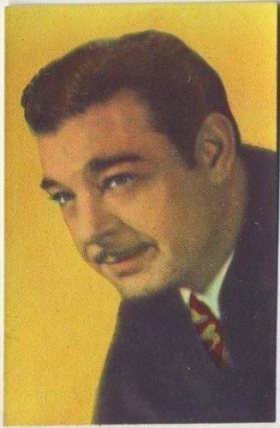

Born Creighton Tull Chaney on February 10, 1906, he spent his earliest years barnstorming vaudeville with his parents, Lon and Cleva Chaney, but any show business career for young Creighton was stalled by the time his parents divorced in 1913. Creighton’s father discouraged his son from embarking upon an acting career, though the young man found himself intrigued by Hollywood and his father’s unique screen stardom. By the time Creighton reached adulthood, Lon Chaney was still terrorizing moviegoers, but his son had to settle for a place out of the limelight. Creighton Chaney took on jobs that called for hands-on work, eventually settling into a position as a plumbing contractor and marrying the boss’s daughter in 1926.

It wasn’t until after a throat hemorrhage claimed the life of his famous father, “Man of a Thousand Faces,” Lon Chaney, at age 47 in August 1930, that Creighton felt comfortable embarking upon his own acting career. Despite a steadfast refusal to capitalize upon his late father’s name, in 1932 he landed a contract with RKO where he played bits and supporting roles under his own name, Creighton Chaney. You’ll find a baby-faced Creighton in a variety of entertaining RKO Radio releases such as Bird of Paradise (1932), Lucky Devils (1933), and The Life of Vergie Winters (1934).“I am not Lon Chaney, Junior. If my father had wanted me to have that name, he would have given it to me. He called me Creighton Chaney and Creighton Chaney I’m going to remain!” (Walker 105).

That is, until 1935. He caved, but he caved for good reason and with dignity:

“I tried for three years to make a go of things without capitalizing upon dad’s name, but the cards have been stacked against me. If I had only myself to think of, I would battle it out to the end. But I’m getting older every year and I don’t think it’s right to make my family suffer just so I can fight for a principal” (Chaney Entertainment).

Even so, it still took Lon Chaney Jr. another four years to make a name—for himself. He signed with 20th Century Fox for $125 per week in January 1937, and he was let go at exactly the same salary, exactly two years later (Mank 440). Towards the end of his time there Chaney Jr. was cast in supporting roles in major films like Jesse James and Union Pacific (both 1939), but otherwise his career had plateaued on a low, level plane just like his salary.

“Things looked rather dark professionally a few months ago,” he told Kolma Flake of Hollywood magazine about that period. “Then Wally Ford had sufficient love for my father and enough courage of his own to cast me as Lennie in Of Mice and Men in the West Coast stage production. Critics opinions were very good and I feel that out of that will come something” (Flake 56).

It did, but only after Chaney Jr. bowled over director Lewis Milestone to wrest the movie role away from Broadway’s Lennie, Broderick Crawford, in the acclaimed 1939 United Artists film release of Of Mice and Men. Chaney Jr.’s performance was so visceral that it inspired near immediate parody (as soon as Tex Avery’s Of Fox and Hounds for Leon Schlesinger’s Merrie Melodies in December 1940), while so touching that it’s still hard not to shed a tear upon encountering it today. Produced by Hal Roach Studios, Of Mice and Men received four Academy Award nominations including Best Picture, which was awarded to Gone With the Wind (1939) that year. Roach used Chaney again in the caveman cult favorite One Million B.C. starring Victor Mature and Carole Landis.

Meanwhile, the monster movie was back at Universal. They had been wiped from the programming slate after the Standard Capital Corporation took control from the Laemmles in March 1936. Then a couple of years later something funny happened.

In August 1938, a theater proprietor in Beverly Hills was looking for films to fill the triple bills he had been running. He made a deal pairing the original Dracula and Frankenstein with Son of Kong (1933), and found himself with such a crowd on opening night that he had to call on the police to maintain order. Son of Kong was dropped from the bill on the second night, and by the fourth night the exhibitor had made a deal to keep running the Universal chillers indefinitely. The sensation spread throughout the country and by October Universal announced that a total of five hundred prints had been ordered to fulfill the demand for this “twin-horror” bill (Horror Dual, 1; Need 500, 2).

The following month Son of Frankenstein (1939) was in production and horror had returned to Universal.

In early December 1940, Universal announced the signing of Lionel Atwill to play the title role in The Mysterious Dr. R. The project was based on a story called “The Electric Man” that Universal had bought for Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi back in 1935. Karloff and Lugosi would reunite later, but Black Friday (1940) had been their fifth and final pairing at Universal—I say pairing, but Black Friday is infamous for never actually pairing the two horror icons on the screen at the same time.

Subsequently, Lugosi continued in supporting roles for Universal and also busied himself in several Poverty Row releases (especially for Monogram), while Karloff was off to New York in January 1941 to begin rehearsals for the long-running Broadway hit, Arsenic and Old Lace. From early 1941 through late 1944 Karloff’s stage commitments only allowed him time to appear in one film (The Boogie Man Will Get You [1942] for Columbia). The horror movie still had legs, but its most reliable monster was unavailable.

“The Electric Man” was eventually adapted by George Waggner, who also directed the 1941 film that released as Man Made Monster. While Atwill is at his devious best in the film, the title change alone is indicative of Universal’s pleasure with second-billed Lon Chaney Jr., who played the titular monster created by Atwill’s Dr. Rigas.

Above: Lon Chaney Jr. in Man Made Monster (1941).

The underrated Man Made Monster is a fast-paced, well-acted, and visually exciting Universal horror film that belongs at least towards the top tier of all but their most classic monster titles. Chaney Jr.’s monster-movie debut was so well-received that Universal put him (and Waggner) under contract in a deal that paid off mightily before the year was through!

Not immediately though. Despite the success Lon Chaney Jr. enjoyed with the March 1941 release of Man Made Monster, he spent most of 1941 filling out the casts of musicals and westerns for Universal. With little fanfare Universal began production upon a Curt Siodmak script tentatively titled Destiny on October 27, 1941.

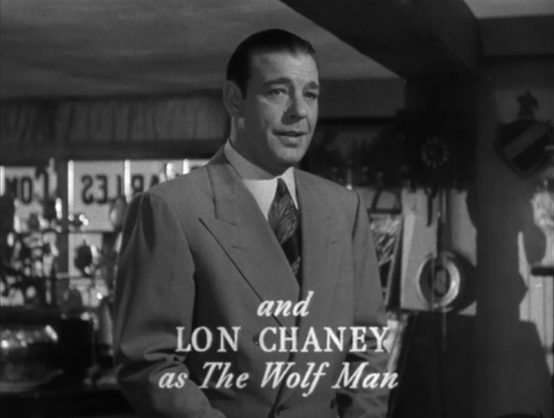

The opening credits introduce a sterling group of cast members, each shown in brief clips from the film to follow, punctuated by an image of Chaney as the character we soon meet as Larry Talbot. But Larry Talbot isn’t mentioned in these credits, instead we’re teased by the caption, “And LON CHANEY as The Wolf Man.” The “Jr.” has been dropped from Chaney’s billing for the first time, and so I’ll also drop it as we proceed.

First billed after the title was Claude Rains, who claims his own unforgettable horror credit as star of The Invisible Man (1933), but by this time had also appeared in Warner Bros. titles such as They Won’t Forget (1937), The Adventures of Robin Hood, Four Daughters (both 1938), Juarez, and They Made Me a Criminal (both 1939), plus played an unforgettable supporting role for Frank Capra at Columbia in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). Other supporting roles in The Wolf Man were less demanding parts that ordinarily would have been played by lesser known actors, but Universal cast a recognizable yet affordable group of faces, such as pre-Code king Warren William; sturdy “other man” Ralph Bellamy; and Warner’s former threat to Errol Flynn, fresh-faced Patric Knowles.

If the Chaney name and the creepy title didn’t quite spell out horror for you, The Wolf Man also boasted the brief, but memorable presence of Bela Lugosi, whose character Bela is the only werewolf in action during the first half of the movie. Acting coach Maria Ouspenskaya runs so well with her supporting role that she remains better remembered for her gypsy woman Maleva than she is for the two Academy Award-nominated roles she had played prior to The Wolf Man. (Ouspenskaya received nominations for Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Dodsworth (1936) and Love Affair (1939).)

Then there’s Chaney’s leading lady Evelyn Ankers, who notches her most famous portrayal on the way to becoming the “Queen of the B’s” through work in additional genre titles like The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Captive Wild Woman, Son of Dracula, The Mad Ghoul (all 1943), Weird Woman (1944), and a host of other roles including two appearances in the Sherlock Holmes series.Before we get to see any of these actors interact with one another, an encyclopedia is pulled from a row of books and opened to the following entry:

“LYCANTHROPY (Werewolfism). A disease of the mind in which human beings imagine they are wolf-men. According to an old LEGEND which persists in certain localities, the victims actually assume the physical characteristics of the animal. There is a small village near TALBOT CASTLE which still claims to have had gruesome experiences with this supernatural creature.

The sign of the Werewolf is a five-pointed star, a pentagram, enclosing a …”

According to director-producer George Waggner, an executive at Universal insisted the word “legend” be presented in all capitalized letters.

This stress on legend opens up some interesting possibilities for The Wolf Man that Waggner had discarded by the time of the final version of the script.

There was a major change in the background of Chaney’s character, who screenwriter Curt Siodmak originally intended to be Larry Gill, an American engineer visiting Talbot Castle to install Sir John’s (Claude Rains) telescope. Larry Gill became Larry Talbot, Sir John’s second-born son returning home from America after the death of his older brother in a hunting accident. The change takes what would have been an incidental connection between the Chaney and Rains characters, and instead allows them to try to close the awkward distance caused by their long separation amid the outside forces of terror about to be unleashed around Talbot Castle. Larry calls Sir John “Sir” during an early portion of The Wolf Man. Before the movie ends he’ll call him “Dad.”

Another major change to the script is far more intriguing in that it would have added a thick layer of ambiguity to the question as to whether or not Larry or anybody else in the film had actually physically transformed into a wolf man.

As film historian Tom Weaver points out in his highly recommended commentary track on Universal’s DVD release of The Wolf Man, a lot of the dialogue that made it into the final version of the film also works in an alternate arena where Larry’s lycanthropism remains a delusion within his own mind (Weaver, “Commentaries”). Warren William doesn’t get to do much in The Wolf Man as Dr. Lloyd, but practically every line he utters would fit into either version of the story. Brian Eggert of the Deep Focus Review website posted an excellent online review of the film from this alternate perspective in which The Wolf Man “contains no monster at all,” and “this initial film (of the Wolf Man series) is about madness as a symptom of duality, not some supernatural creature of the night.”

Almost all other critics dismiss this possibility because we do see Larry Talbot as the Wolf Man, three times, in fact. And that is assuredly what Universal, Waggner, and—after several revisions— Siodmak meant. In any case, I find myself now watching the film from both of these perspectives. To experience a more literal version of what might have been, do have a look at the 1951 Realart Pictures release Bride of the Gorilla, which was written and directed by Siodmak and features Chaney Jr., albeit in a supporting role. (Raymond Burr is the “monster.”) Do have a look, I say, it’s fun, but don’t raise expectations very high.

All this talk of delusions, mental suggestion, and mass hypnotism, combined with werewolf legend builds the horror element of The Wolf Man leading to an uneasy anticipation of the appearance of an actual monster. Making this anticipation all the more horrifying is the fact that our hero, fresh-faced American Larry Talbot, is an outsider experiencing and hearing all of this for the first time—just like us.

All the poor kid wants to do is reestablish his roots around Talbot Castle and date the pretty young woman he spied through his father’s telescope. But before Gwen Conliffe (Evelyn Ankers) even agrees to accompany Larry on the town, she’s introduced him to werewolves, pentagrams, and that famous old poem of legend that originated from the mind of screenwriter Siodmak:

“Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.”

Larry brushes this all off, happy to buy a cane featuring a big silver wolf’s head as its handle in order to further ingratiate himself with Gwen, who he insists on meeting again later that night. Larry pops home in the meantime and shows off his spiffy new accessory to his father, who offers a bit more about werewolves, even if he’s no believer himself:

“But like most legends, it must have some basis in fact,” Sir John says. “It’s probably an ancient explanation of the dual personality in each of us.”

Sir John then repeats the poem Gwen had recited to Larry. Larry finds it odd that his father recites the same legend to him, but at this point the viewer is dwelling upon that much more than Larry, who’s more excited to whisk Gwen away later that evening.

When he meets Gwen she surprises him by calling her friend Jenny (Fay Helm) out of the shadows to accompany them to the gypsy carnival. Larry is happy as a lark as he walks the two women through the foggy night and the iconic scenery that is forever associated with danger by anybody who has already seen the movie. Jenny grabs an armload of wolfsbane and then recites the old poem once again before the trio come upon Bela the gypsy (Lugosi) at the outskirts of the carnival. Larry and Gwen have so charmed one another that they leave Jenny alone with the creepy gypsy to have her fortune told.

While Larry practically pins a willing Gwen against a crooked tree, where she apologizes for her engagement to another man (Knowles), inside Bela’s tent legend is turning into fact.

A groggy Bela thrusts Jenny’s wolfsbane to the ground as he tries to overcome a vision of a pentagram on her palm, a sign that marks her as the next victim of the werewolf. Jenny freaks out when Bela commands her to leave, running off, but not fast enough. Back in the foggy pick-up area Larry and Gwen’s attentions are broken from one another by an eerie wolf’s howl in the near distance. While the howl freezes them, Jenny’s screams send our hero bolting away from his lady love and into the night where he confronts the horrifying sight of a wolf on all fours tearing Jenny to shreds.

Larry launches himself at the wolf, engaging in a life and death brawl, mostly obscured by the crooked trees, and ending when Larry begins to beat the wolf with the silver-topped end of his cane. Larry stumbles away from the scene of his kill reeling from the wolf’s bite. The old gypsy woman Maleva (Ouspenskaya) happens along and helps Gwen get Larry home.

“Wolf? Gypsy woman? Murder? What is this?” Colonel Montford (Bellamy) proclaims in perfect tone upon Larry’s staggering entrance.

It turns out Bela the gypsy has been murdered. Larry’s told that there was no wolf, and Larry is shown that there is no wolf bite upon his body. Everybody in town assumes that Larry killed Bela the gypsy, and an unforgiving group of women led by Jenny’s mother (Doris Lloyd) are quite sure that Larry also bears responsibility for Jenny’s death.

“Very strange there were no murders here before Larry Talbot arrived,” she says.

It wears on formerly happy-go-lucky Larry, who lashes out at anyone suggesting that anything happened other than what he believes he experienced. This includes practically everybody surrounding him with one exception: Maleva the gypsy woman, who offers information, advice, and protection to the outsider who has killed her son.

“Whoever is bitten by a werewolf and lives becomes a werewolf himself,” Maleva tells Larry before offering him a necklace with a charm as protection.

Maybe this would have worked—Maleva seems to know what she’s talking about—but Larry almost immediately passes the charm onto Gwen, sacrificing his own welfare for her protection. And it is a sacrifice because in the act of giving Larry is admitting that the charm offers protection.

“I never accepted a present without giving something in return,” Gwen says. She offers him a penny, but Larry takes a kiss. Gwen then flees the scene, but before Larry can follow he’s distracted by gypsies scampering from camp after Maleva spreads word of a werewolf. Larry is left in the swirling montage of a flashback bringing us all up to date with the truth and his tragedy, one and the same, and about to be shown through the details of Larry’s first transformation, a little over forty minutes into The Wolf Man.

Forty minutes spent building a legend.

It had always been there, but never so specific. “This book is a monograph on a peculiar form of popular superstition, prevalent among all nations, and in all ages,” Sabine Baring-Gould writes in The Book of Were-Wolves, published in 1865 (Baring-Gould, xi). An impressively complete text in collecting myth, legend, and science surrounding lycanthropy around the world and throughout the ages, perhaps Baring-Gould’s book found a place on the well-researched Curt Siodmak’s werewolf-reading list. Nevertheless, despite all of the detail presented in this surprisingly readable antique text, I’d still say most of what I know about werewolves dates no earlier than December 1941.

When I think werewolf, I think Lon Chaney. I also think Jack Pierce, the legendary head of the Universal make-up department, associated to some degree with all of their monster creations of the 1930s and ‘40s. Chaney’s wolf man, with its artificial snout and layers of yak hair, is among Pierce’s most legendary creations.

Granted, I am a fan of Universal’s earlier werewolf release, Werewolf of London (1935) starring Henry Hull and Warner Oland, but that offering failed to capture the public’s imagination in the same way as The Wolf Man’s tragic everyman Larry Talbot did. Pierce’s make-up is more conservative in the earlier movie, but the lack of attraction has more to do with the rigid personality of the Hull character.

On the other hand, Chaney’s Larry Talbot starts out brash, but likable. He’s confident, courageous even. After he tangles with the wolf, Larry is upset, disturbed, angry, but most of all scared. With so many Americans soon headed overseas to face strange and terrifying circumstances, an audience could soon relate. Larry has earned a lot of leeway for his actions by this point, because by this time we already like the big lug.

For some reason contemporary reviews of The Wolf Man presented the movie as old hat, but other than Hull’s werewolf and a couple of earlier silent releases, there just weren’t that many werewolf movies around by that time.

“The fantastic legend of the werewolf again is brought to the screen,” wrote Charles S. Aaronson of Motion Picture Daily, whose thirst for werewolves must have been satisfied by Universal’s earlier release, six years prior to this one. Aaronson, who viewed the film in Universal’s projection room on December 9 with other critics, did find the film exploitable merchandise, praising it for having “a full measure of suspense and thrill” Aaronson, 8).

“Weaknesses are familiarity of the subject (and inadequacy of the dialogue),” said Motion Picture Herald, who must have been worn out by a decade of horror films rather than any nonexistent glut of werewolf movies. While their reviewer praised “photograph, settings and some performances,” the review forfeits its reliability in criticizing “Siodmak’s script, which falls far short of the Universal standard of effectiveness in the field of the horror film” (“Reviews,”420).

I have to wonder if Theodore Strauss of the New York Times even bothered to watch the movie: “the wolf man is left without a paw to stand on; without any build-up either by the scriptwriter or director,” he writes before slipping in the Disney gibe I mentioned at the open. No build-up? Was this guy on line for popcorn during the first forty minutes of the movie?

I have to wonder if Theodore Strauss of the New York Times even bothered to watch the movie: “the wolf man is left without a paw to stand on; without any build-up either by the scriptwriter or director,” he writes before slipping in the Disney gibe I mentioned at the open. No build-up? Was this guy on line for popcorn during the first forty minutes of the movie?

The Film Daily was among the few trade papers who got it right when reporting upon The Wolf Man: “Many of the elements found most effective for producing goose pimples and spine chills are found in this yarn of murder, psychiatry, superstition and romance,” their reviewer wrote, concluding “It’s pretty fantastic, but none the less stirring stuff which will have the ‘horror’ seekers on chair edge” (“Reviews,” 6).

Variety, despite their leeriness over timing, was also on target: “‘The Wolf Man’ is a compactly knit tale of its kind, with good direction and performances by an above par assemblage of players” (“Film Reviews,” 8).

Returning to the action of the film, Larry is terrified as he comes to believe that he is in fact a werewolf.

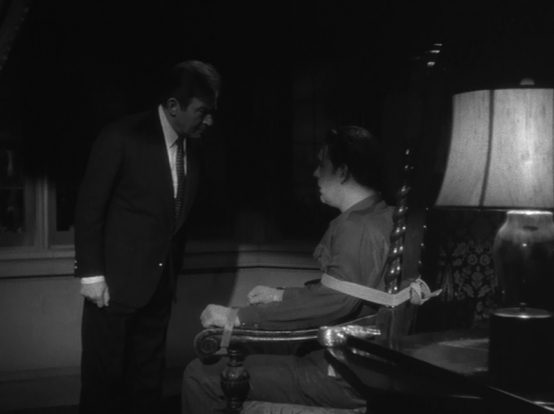

“They’re out hunting for me!” Larry tells his father. Sir John scolds his son for abandoning common sense in favor of the ravings of a gypsy woman, but he takes some pity on his son and offers help. Sir John binds Larry into a chair and confirms all of the windows are locked. He’ll lock the door on the way out.

“Now you’ll see that this evil thing you’ve conjured up is all in your mind,” Sir John says, words which will make the outcome of this night all the more tragic.

Sounding like a little boy, Larry utters hope that Sir John stay by his side.

“Oh no, I’ve got to go, Larry. These people have a problem, you must make your own fight.”

Larry convinces his father to at least take along his silver-topped cane. Sir John carries it when he encounters Maleva the gypsy woman in the night. Sir John is standoffish, yet worried for his son. He should be, as the Wolf Man is now loose.

When the monster takes Gwen in his clutches it’s Sir John who responds, beating the impossible creature over the head with the silver end of Larry’s cane. If he’s shocked to have a Wolf Man dead at his feet, he’s devastated to watch it revert to its familiar human form as Maleva utters the same epitaph she had spoken earlier over the corpse of her own dead son:

“The way you walked was thorny through no fault of your own. But as the rain enters the soil, the river enters the sea, so tears run to a predestined end. Your suffering is over. Now you will find peace for eternity.”

Or at least until Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943).

The Wolf Man earned over a million dollars in just a few months, breezing past its cost of $180,000 and earning bonuses for Waggner and executive producer Jack J. Gross (Weaver, 262). And that only represented The Wolf Man’s first legs. Chaney monopolized the Wolf Man part, playing it again in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945), and ultimately Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). In addition to being Universal’s only Wolf Man in the 1940s, Chaney was also made-up as Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Mummy throughout the decade for the studio.

That second cycle of Universal horror that had begun with Son of Frankenstein in 1939, wound down with House of Dracula in 1945. It was a period dominated by Lon Chaney. Abbott and Costello breathed new life into the monsters near the end of the decade, but despite how serious Chaney and Lugosi take their roles, that one obviously played for laughs.

In June 1957, Screen Gems took a ten-year lease on 550 feature films from Universal’s back catalog. The Wolf Man was among the fifty-two movies in their Shock! package, which began playing on television around the nation that fall. Universal’s classic monsters rose from the scrap heap and created a sensation among Baby Boomers that is still felt today.

Boomers formed a willing circulation base for Forrest Ackerman’s Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, and they lifted Bobby “Boris” Pickett’s “Monster Mash” to number one on the Billboard charts by October 1962. That same month they thrilled at Lon Chaney made-up as the Wolf Man alongside Boris Karloff and Peter Lorre on the Halloween episode (“Lizard’s Leg and Owlet’s Wing”) of the Route 66 television series. They bought toys, models, and trading cards. They ate up strange TV sitcoms like The Addams Family and The Munsters; then home video releases of key Universal horror titles in the 1980s; the 1997 US commemorative stamp issue. Even now, Turner Classic Movies earns praise from fans whenever they manage to license Universal horror classics like The Wolf Man for their Halloween-themed horror programming.

Universal’s horror classics remain among us. And The Wolf Man remains front and center with Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Mummy.

“That’s my baby,” Lon Chaney said of the Wolf Man (Borst). It sure was. It may be a backhanded compliment to say Chaney never did anything better after The Wolf Man movies, yet he’s always a welcome presence, no matter how low the budget or our expectations. He did distinguish himself in supporting roles in non-horror classics like High Noon (1952) and The Defiant Ones (1958), but there were more misses than hits after his 1940s peak. Still, it’s impossible for fans of The Wolf Man not to smile whenever Lon Chaney fills the screen.

“That’s my baby,” Lon Chaney said of the Wolf Man (Borst). It sure was. It may be a backhanded compliment to say Chaney never did anything better after The Wolf Man movies, yet he’s always a welcome presence, no matter how low the budget or our expectations. He did distinguish himself in supporting roles in non-horror classics like High Noon (1952) and The Defiant Ones (1958), but there were more misses than hits after his 1940s peak. Still, it’s impossible for fans of The Wolf Man not to smile whenever Lon Chaney fills the screen.

Bad timing? Maybe the critics had forgotten how well Dracula and Frankenstein had resonated with audiences in the lean times of 1931. The Wolf Man was in fact well-timed entertainment in the wake of the attack upon Pearl Harbor, and it was still around to offer distraction during the Cold War’s hottest moments. It’s very likely at your fingertips today if you need a little escape after a rough day. The Wolf Man now transcends time.

This article originally appeared just over one year ago in Classic Movie Monthly #2 for Kindle. Most of the images (all of the screen captures) are new to this post.

References

- Aaronson, Charles S. “Reviews: The Wolf Man.” Motion Picture Daily. December 10, 1941.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine, M.A. The Book of Were-Wolves: Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition. London: Smith, Elder and Co, 1865.

- Borst, Ron. Biography – Lon Chaney: Son of a Thousand Faces. Directed by Kevin Burns. 1995; Twentieth Television, A&E Home Video. Web, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s1VfY8IJ0qE.

- Eggert, Brian. “The Definitives: The Wolf Man (1941).” Deep Focus Review. February 10, 2010, http://www.deepfocusreview.com/reviews/wolfman.asp.

- “Film Reviews: The Wolf Man.” Variety. December 17, 1941.

- Flake, Kolma. “Signs of Success.” Hollywood. July 1940.

- “Horror Dual Revival Stirs General Box-Office Riot.,” Motion Picture Daily. October 19, 1938.

- “Lon Chaney, Jr.” Chaney Entertainment. Accessed September 27, 2016. http://lonchaney.com/lon-chaney-jr/.

- Mank, Gregory William. Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting Collaboration. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.

- “Need 500 Prints to Meet ‘Twin-Horror’ Bill Dates.” Film Daily. October 7, 1938.

- Strauss, Theodore. “The Screen.” New York Times. December 22, 1941, http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9E00E7DC173DE333A25751C2A9649D946093D6CF.

- “Reviews of the New Films: The Wolf Man.” Film Daily. December 10, 1941.

- “Reviews: Wolf Man.” Motion Picture Herald. December 20, 1941.

- Walker, Helen Louise. “What About the Second Generation?” Modern Screen. July 1932.

- Weaver, Tom. “Commentaries.” Disc 1, The Wolf Man, The Legacy Collection DVD. Directed by George Waggner. Universal City, CA: Universal Studios, 2004.

- Weaver, Tom Michael Brunas, and John Brunas. Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931-1946. 2nd edition. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007.

Leave a Reply