I had seen pictures of the Wild Children of revolution-racked Russia. I had read of the free youth of Germany after the World War. I knew that in every nation, following a plague, an invasion, or a revolution, children left without parents and homes became vagrants.

Before my own experiences I had always believed that in America we managed things better (Minehan xvi).

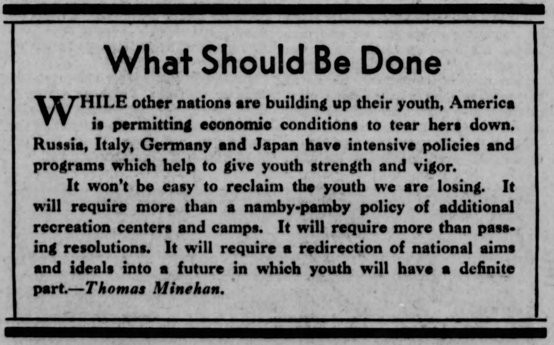

Before Wild Boys of the Road came to America’s movie houses, a sociologist named Thomas Minehan had spent two summers, plus weekends and holidays, integrating himself among America’s youth on the road. The result was his classic study Boy and Girl Tramps of America, which itself wasn’t published until 1934, several months after Wild Boys of the Road had premiered in September 1933. The movie had been a response to newspaper headlines about America’s transient youth, and it in turn helped keep the subject alive and raise interest in Minehan’s accessible study when it appeared. A title that ordinarily may have only been read by academics and shelved by Universities fell into the hands of a large mainstream audience who heard about it from those same newspapers already publicizing the problem and promoting the recent film.

When I first met Wild Boys of the Road, as someone who had grown up in a comparatively cozy era two generations removed from The Great Depression, it seemed more like an alternate history that could have never happened than any sort of former American reality. It’s depressing stuff, and hard to take, these children on the lam, losing limbs, risking rape, living in sewer pipe cities, and doing their best to grin and bear it without stopping to think tomorrow will probably be worse.

Credit three excellent lead actors for lightening this dose of reality. Director William A. Wellman also includes many little touches to occasionally lighten the mood, whinnying horses and stolen cakes, the wrinkly-nosed smiles of the actress he’d soon marry, and Sterling Holloway doing pretty much anything, as usual. Then there’s the athleticism of star Frankie Darro bunny-hopping into a trash can or letting loose with a series of handsprings, youth keeping him an admirable bundle of energy no matter how downtrodden life is around him. But the overall tone is morbid, and even the happy ending doesn’t seem so very happy if you stop to think about it on the way out of the theater. The future is bleak.

The trade papers had a love-hate relationship with Wild Boys of the Road, though their inclinations proved wrong with paying audiences. “Fact is that while the picture has been very well done, indeed, it should never have been done at all for general commercial release,” said Variety. Good intentions, but lousy business sense they surmised, daring to release a film whose “every incident, every character ceaselessly brings to mind the most gruesome underside of the hard times.” A writer for fan magazine Screenland damned it as just another horror film, beginning with comparisons to Frankenstein before detailing every moment of the shocking scene of a character losing his leg, and concluding, “The agony of the boy induced many in our audience to deplore that scene, and it succeeded only in upsetting us.” Way over on the other side of the spectrum, Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times criticized the film for not going far enough. He deplored those lighter touches I mentioned, and thought “its tragedy has been oversentimentalized, its drama is mostly melodrama and, by endowing it with a happy ending, the producers have robbed it of its value as a social challenge.”

Too much, too graphic, not enough: such wildly varying opinions from three experienced film viewers, each speaking to a different audience, help illustrate the power of Wellman’s film.

Frankie Darro plays Eddie, whose world is upset when he learns of best pal Tommy’s (Edwin Phillips) financial hardship, and completely capsizes when he finds out his family has it just as bad. After Eddie sells his car and pops the proceeds into the family kitty, he and Tommy decide the folks would have an easier time without them around to support. The teens decide to fly the coop without a world of good-bye. Eddie leaves behind an encouraging note promising that he’ll send money once settled into greener pastures. From brainstorm to departure, it’s mere minutes before Eddie and Tommy hop their first freight train and settle in for an uncomfortable night’s sleep on a breezy flat car, almost entirely open to the elements.

Eddie and Tommy rise with an appetite, but the sandwiches they packed are missing. They turn their suspicions on the only other tramp resting on their car, who Eddie awakens, confronts, and winds up with a pop in the nose for his trouble. Eddie then goes on the attack, but is repelled by a high-pitched scream and comes up startled, his nose dripping blood, as he realizes, “He’s a she!” She is Sally (Dorothy Coonan), and she’s all tears for the moment, but she’ll be strong through most of what follows. After Tommy discovers their sandwiches in another pack, Eddie offers one to Sally, who first refuses on principal, and then gives into hunger, yanking the sandwich from his hand and gobbling it up.

The trio meet up with other youthful wanderers and the most intriguing parts of Wild Boys of the Road becomes the escalating episodes of vagrancy in the middle of the movie. The parts that terrorized and turned off early reviewers. Most of the highlights come on the trains or in the railroad yards, though I’m partial to the scene when Sally discovers her aunt is a madam after the cops arrive to make a pinch. There are no greener pastures. In addition to the more shocking single scenes are a series of confrontations with authority, adults who take no pleasure in their duty, but whose service demand they take the proper steps and shoo away the vagabonds to the next town. Everyone feels for them, but nobody wants them.

Minehan’s experience:

The young tramps seldom remain a week in any community. Relief policies force them to move. In addition, there is the lure of the road inspiring them with hope of better times just beyond the hills and a nervous ‘itching foot’ for travel per se. It was, in truth, impossible for the transient boy or girl to stay anywhere when this study was made. Relief authorities gave a meal and an invitation to move on. No matter how tired he or she was, how willing to work, how weary and disgusted with the road and its aimless wandering, he had to take to it. Police did not trouble transients so long as they kept moving. As soon as they attempted to halt, however, police acted. Jungles were raided, soup and bread lines searched for non-residents, mission lists combed. The child tramp was out again on the road (54).

The author spent two years learning what Warner Bros. and Wellman show us in a tight 68 minutes.

Our main trio, Eddie, Tommy, and Sally, follow the map east, eventually settling in New York, where opportunity finally knocks when Eddie is offered a job as an elevator operator. Unfortunately, the position is contingent upon his acquiring an alpaca coat, which runs about three bucks, so out to the streets our trio take to panhandle the required funds.

Just three dollars from freedom, an independence that would have made for a more interesting ending than either the script’s original law-and-order conclusion packing our heroes off to various detention centers, or the studio’s revised bit of open-ended charity that provides just enough of a happy ending for us to get out of the theater. But it all goes wrong. Eddie, Tommy, and Sally are hauled into court where they face a judge (Robert Barrat) who wants to be kind, but who finds himself unable to offer leniency when the youths cannot truthfully answer either who they are or where they come from. Finally, Eddie speaks, his answer a verbal smack meant to redden faces on both sides of the screen:

I knew all that stuff about you helping us was baloney. I’ll tell you why we can’t go home. Because our folks are poor. They can’t get jobs. And there isn’t enough to eat. What good will it do you to send us home to starve? You say you’ve got to send us to jail to keep us off the streets. Well, that’s a lie. You’re sending us to jail because you don’t want to see us. You want to forget us. Well, you can’t do it. Cause I’m not the only one. There’s thousands just like me. And there’s more hitting the road every day.

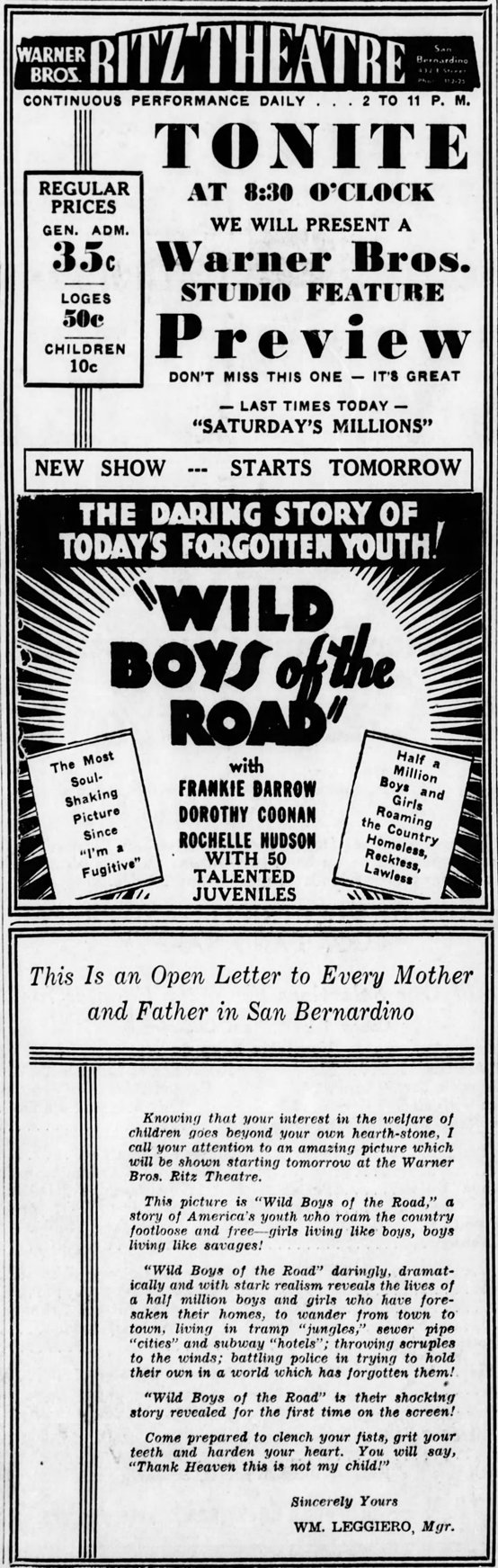

Frankie Darro, who previously appeared for Wellman at the opening of The Public Enemy (1931), leads the cast and the honors. A great talent, blessed with the skills of a Mickey Rooney, but cursed by similar stature and a less trustworthy face, Darro otherwise had all of the tools for stardom. His biographer and friend, John Gloske, noted that this was Frankie’s favorite of his movies, and wrote that “until his death he would keep a newspaper stuffed away that he would gladly pull out and show to guests,” a front page that showed the huge crowd surrounding the premiere of Wild Boys of the Road (57).

Edwin Phillips, who acted in barely any other movies, holds his own alongside Frankie, and is especially good with him after the tragedy in the railroad yard, and later in the sewer pipe city, where he struggles to come to terms with the physical maladies of the road. Dorothy Coonan, who director Wellman married after completion of Wild Boys of the Road, is involved slightly less than the two boys, but is as much of a charmer to audiences as she is to all of those adults in the movie who scrunch their noses back at her.

The supporting cast is filled with familiar faces including Rochelle Hudson as Eddie’s date at the beginning of the movie; Grant Mitchell and Claire McDowell as Eddie’s parents; Minna Gombell as Sally’s aunt; Sterling Holloway as the oddball drifter; Ann Hovey as the poor girl who Ward Bond stumbles upon; Willard Robertson as the detective sorting through the kids off the train; Arthur Hohl, playing nice as a jungle surgeon; and Robert Barrat as the juvenile court Judge pitying the kids.

While director William A. Wellman’s bits of humor, whether you find them quaint or cornball, stand out as all his own, so does his more special talent of illustrating complicated relationships between men, or, in this case, boys. Wellman’s most personal movies are often touched the most influential experience of his life, the unique and intimate ties he forged with his fellow soldiers during the Great War. What he took out of this is an ability to show the close attachment two men are capable of forming with one another as loving brothers, a brotherhood that reaches beyond any simple surface friendship. Eddie and Tommy begin Wild Boys of the Road as old pals, and the Depression immediately lands its first shots when the haves eject have-not Tommy from the dance. The hardships of the road only bring Eddie and Tommy even closer together. They are each their own man, proud and independent, yet of a shared experience that makes for an unbreakable bond.

While director William A. Wellman’s bits of humor, whether you find them quaint or cornball, stand out as all his own, so does his more special talent of illustrating complicated relationships between men, or, in this case, boys. Wellman’s most personal movies are often touched the most influential experience of his life, the unique and intimate ties he forged with his fellow soldiers during the Great War. What he took out of this is an ability to show the close attachment two men are capable of forming with one another as loving brothers, a brotherhood that reaches beyond any simple surface friendship. Eddie and Tommy begin Wild Boys of the Road as old pals, and the Depression immediately lands its first shots when the haves eject have-not Tommy from the dance. The hardships of the road only bring Eddie and Tommy even closer together. They are each their own man, proud and independent, yet of a shared experience that makes for an unbreakable bond.

The story was adapted for Wellman by Earl Baldwin from an original by Danny Ahearn, who is probably the most interesting character with any hand in this classic. Ahearn, who also wrote the original story that Warner Bros. turned into Picture Snatcher (1933), was promoted as the man who committed—and got away with—a couple of murders. He had credibility along those lines as author of a book called How to Commit a Murder (And All the Major Crimes on the Calendar and Get Away With It), which supposedly fulfilled the promise of its title. A review of Ahearn’s book in the July 1930 issue of True Detective described what was inside:

Ahearn tells exactly how to cover one’s tracks after committing a murder. He discusses crime with the flair of one who knows it and he makes it clear that there lives in the midst of the law-abiding people of this country a strange and dangerous group apart. People who have different habits, customs, methods of living, ethics and dangers. People who have no center balance—who are either up in prosperity or down in despair; who are either in or out—and far too many of them out (8).

The critic then concludes, Ahearn’s book is “not merely absorbing–it’s astounding.”

The critic then concludes, Ahearn’s book is “not merely absorbing–it’s astounding.”

As Hollywood got to know him, Ahearn was compared to Jim Tully (who worked on the story for Wellman’s similar Beggars of Life [1928]), but beyond Picture Snatcher and Wild Boys of the Road, the only other story of Ahearn’s adapted to film was Bulldog Edition for Republic in 1936. This mysterious figure was eventually convicted of a robbery and assault that landed him a life sentence in 1948. A technicality lowered that sentence to 15-to-30 years in 1952, with the possibility of parole in six years. Whether Ahearn ever got out or not is a mystery. He died in obscurity in 1960 at age 59.

Wild Boys of the Road was marketed as important and was quickly accepted as such. It was one of several early Warner Bros. titles acquired by the Museum of Modern Art Film Library in 1935, alongside pioneer talking features The Jazz Singer (1927) and Lights of New York (1928), and fellow headline-snatched tales such as I am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (1932) and gangster classics Little Caesar (1930) and The Public Enemy (1931). It seemed to score well with audiences too, beginning as early as its premiere in New York’s Hollywood Theatre, where it was held over a second week, and continuing a few years later with its appearance on a 1936 list of popular reissues said to include, “only those [titles] which exhibitors mention as having done outstanding business on such runs” (‘Marked Trend’).

While Wild Boys of the Road can feel like the flip side of Carvel, an Andy Hardy movie gone awry, it’s another Mickey Rooney movie that makes for a more logical follow-up: Boys Town (1938).

In reality, the new Roosevelt administration quickly attempted to curb the problem of transient youth through New Deal programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps and various services formed under the Federal Transient Relief Service (FERA) and, later, the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The problem was ultimately curtailed by America’s entry into World War II as young men both entered into service and vacated jobs at home, providing opportunity to those who were previously left without work. For those of us who came along later, Wild Boys of the Road captures an American experience that seems beyond belief, yet was thought of as over-sentimentalized by the film critic for the nation’s top newspaper.

This post was written for “The William Wellman Blogathon” hosted by Now Voyaging. The complete roster of contributors, writing about a pretty complete collection of William Wellman movies, is available here.

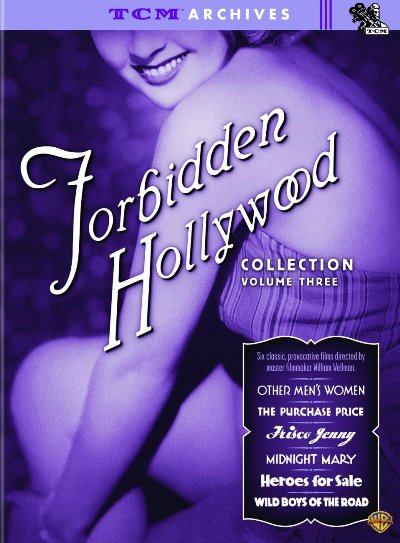

Wild Boys of the Road is one of six movies directed by William Wellman that is included in Warner Home Video’s 2009 DVD set, Forbidden Hollywood Collection Volume 3. Other titles are Other Men’s Women, The Purchase Price, Frisco Jenny, Midnight Mary, and Heroes for Sale. Included among the special features are two documentaries, Wild Bill: Hollywood Maverick, which is more of a traditional documentary, and The Men Who Made the Movies: William A. Wellman, which is packed with Wellman in Wellman’s own words. I’ve probably watched this Forbidden Hollywood Collection more than any of their other sets.

References

- “Author On Crime Given Life Term.” The Daily Times (New Philadelphia OH). 23 Jun 1952, 4.

- “Film Museum’s Acquisitions.” Variety. 9 Oct 1935, 2.

- Harrison, Paul. “In New York.” The News-Herald (Franklin PA). 26 Sep 1933, 4.

- “Marked Trend Toward Reissues and Repeats.” Motion Picture Herald. 26 Sep 1936, 13-16.

- Minehan, Thomas. Boy and Girl Tramps of America. New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1934.

- Nugent, Frank S. “Rev. Of Wild Boys of the Road.” New York Times. 22 Sep 1933. Accessed 12 Sep 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9801EFDB1631E333A25751C2A96F9C946294D6CF.

- Rush. “Rev. of Wild Boys of the Road.” Variety. 26 Sep 1933, 20.

- “Sentenced.” Lubbock Morning Avalanche. 24 Nov 1948, Section 2, Page 12.

- Sullivan, Edward Dean. “New Books and Book News.” True Detective Mysteries. Jul 1930, 8.

- “The Screen Spectator Speaks.” Screenland. Feb 1934, 82.

- “‘Wild Boys’ Holding Over.” Film Daily. 27 Sep 1933, 2.

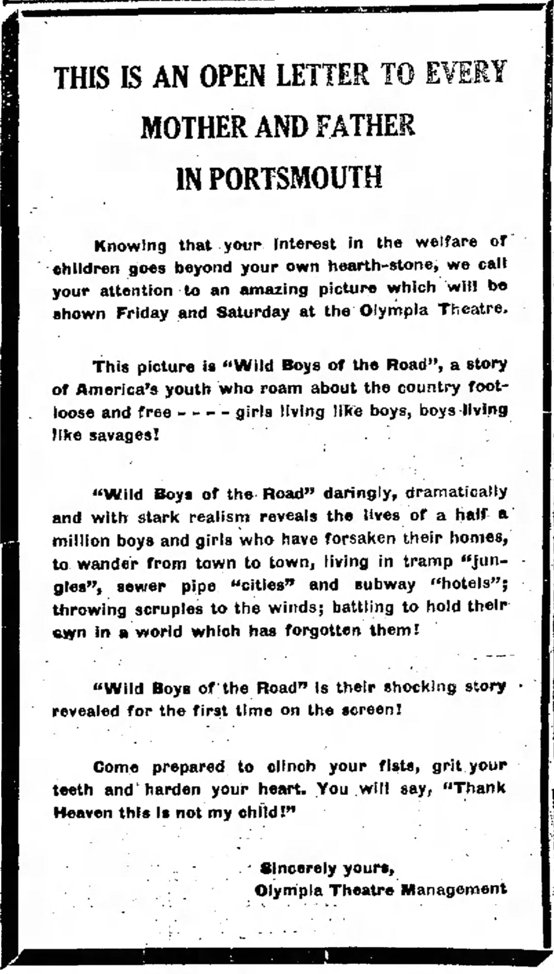

Above: Ann Hovey in the clutches of Ward Bond, the same memorable scene captured in the advertisement above it.

Awesome post as always! Clearly I need to pull out my copy of Forbidden Hollywood again! Thanks for joining the Blogathon!

Thanks, and thanks for hosting! I’m glad I didn’t switch my post, I’d been meaning to cover this one for a long time, and your Blogathon gave me an excuse to just do it!

Excellent. I feel I know the movie, but now I realize I only thought I did. Looking forward to my next viewing through the lens of all the information you provided.

Thanks @Caftan, it holds up so well, I’m sure you’ll enjoy it again!

Excellent piece, Cliff, lives up to its subject. I first became enamored of Wild Boys… in the early ’70s when reading Andrew Bergman’s We’re in the Money, which dangled before me dozens of tantalizing Warner Bros movies then only accessible at the U of Wisconsin or if you could buy 16mm movies, which was way above my pay grade. But this title in particular I yearned to see. And when I finally did see it, amazingly, it lived up to the hype. It’s yet another tribute to Wellman that he could evoke place so effectively when the movie was shot in and around Los Angeles. As for the ending, which bugs so many people to this day, to me it’s like the happy endings of women’s films—you just have to know that the real story is the rest of the movie and ignore it. In these movies the truth is in the travails. … I gather a huge obstacle to Darro’s achieving stardom was his old man, one of those impossible blowhards who insist on doing all the business but who alienate everybody in sight. In this and The Mayor of Hell, Darro breaks my heart. In additioni to the Mick, I see a lot of Cagney in him. Anyway, thanks for the piece and as always for your excellent research! I need to learn how to access the sources you use… the clippings paired with your insights make your work very rich.

Thanks for the comment, Lesley. I agree, Darro is also great in The Mayor Hell, another favorite. Honestly, between his height and his looks, I don’t think he was ever going to be a huge star. At least not beyond these years. I actually don’t mind the ending myself, I just don’t think it’s as happy as its made out to be. I suppose they could have gone the Footlight Parade route, unveiled a banner of FDR and imply there would be New Deal programs to fit all, so a handspring trumps that. Glad it held up for you when you found it, that is always satisfying! The only problem comes after first discovering a gem like this, when you’re left wondering why you can’t find more of the same quality!

Great piece, Cliff. All the information about the real-life inspiration and research which went into the film are fascinating, as is all the publicity material, including that letter supposedly from the theatre management. I agree with you and Lesley that Darro is so talented and it is a pity he didn’t make it as an adult star – but he gave us some great performances in this and The Mayor of Hell.

Thanks, Judy! I was buying on the letter, until I crisscrossed the country and found it again!