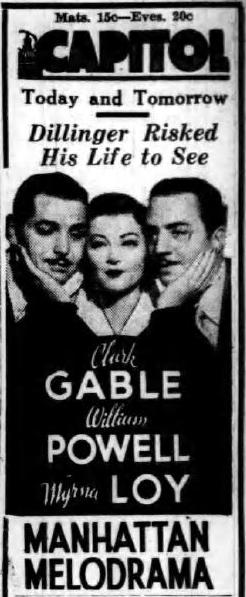

Above: Manhattan Melodrama ad discovered in the Elmira Star-Gazette, August 1, 1934 edition, page 13.

Most of Gable’s performance consists of his typical star turn as the brimming-with-confidence, though not quite obnoxious, he-man loved by men and women alike. He’s a bit more rapid-fire with his delivery than usual, likely the result of W.S. “One Shot Woody” Van Dyke’s direction. In her autobiography Myrna Loy remarked about Van Dyke’s quest for spontaneity, explaining that “speed ensured it” (89). It works here for Gable, who never came so close to playing a rough in the Cagney-manner. Except, again, Gable is not quite obnoxious. Cagney could be.

Gable is special in Manhattan Melodrama during the little moments that see him drop his boyish facade. One of his best scenes is when his girlfriend, Eleanor (Loy), rejects him and his lifestyle. He’s stunned, even hurt, but chooses not to show this to Eleanor, only us. And so, he loses Eleanor. He accepts this in time, telling her she had more on the ball than he ever thought by rejecting him for his much more stable boyhood friend, Jim Wade (Powell). Another such moment comes in Blackie’s final scene, when that same pal who won Eleanor’s love, Jim Wade, tries to avoid saying goodbye. Gable spends most of the scene putting on the cheer for the sake of everyone else, when—but for a moment—every trace of happiness is wiped from him, replaced by a raw sorrow after he reads the despair on his friend’s face. But rather than succumbing to the moment, Blackie bucks up, and Gable lathers up the charm one more time, making a defiant, yet amiable exit from Jim’s life and soon his own. Gable is heartbreaking in his final film, The Misfits (1961), but if you thought it took him that long to learn how to act, go no further than his final scene in Manhattan Melodrama, made over a quarter-century earlier.

Before Gable is Gable in Manhattan Melodrama—Mickey Rooney is. The movie opens with a date, June 15, 1904, that contemporary audiences would identify with memory of the many lost lives on board the passenger steamboat General Slocum. Over 1,000 people perished on what was the deadliest day in New York history until September 11, 2001. Manhattan Melodrama puts its two lead characters on board as children, Rooney as Blackie, already hustling, and Jimmy Butler as young Jim Wade, doing his best to keep his buddy Blackie on the straight and narrow path. Together they come to the defense of another boy and both Blackie and Jim’s fists are flying when a passenger suddenly cries fire. There’s panic on board as the passengers scramble, trampling each other in the quest for life preservers that, in real life at least, largely turned out to be defective. Young Blackie leaps from the boat to the water below and Jim follows, doing his best to keep his friend’s head above water. Both boys are saved when friendly Father Joe (Leo Carrillo) follows them into the water and safely swims them ashore.

The next scene is horrifying as the survivors mourn over the bodies of those who didn’t make it. Blackie is crying over his mother’s corpse when Jim, also newly orphaned, finds him. Nearby the father of the Jewish boy who Blackie and Jim had been fighting for mourns over his son’s body. He was a good boy, Blackie reassures the man, who soon suggests the two boys come live with him. “But I’m not a Jew, and neither is Jim,” Blackie says. Then George Sidney, an actor often cast in comic parts, but here playing the man the boys soon call Poppa Rosen, is gifted with the greatest line of his career: “Catholic, Protestant, Jew, what does it matter now?” Poppa Rosen is then almost immediately dispatched after a Trotsky rally turns riot and the mounted police rush from their stables and over Poppa Rosen. The kind father figure is left trampled into the dirt with the boys crying over him as they so recently had over their parents during the Slocum disaster.

The calendar then progresses, the dates backed by a split screen montage depicting Blackie’s gambling on one side and Jim’s study towards a law degree on the other. It’s only been a few weeks since the friends last saw each other, but we meet them as men, now played by Gable and Powell, who catch up with one another on September 14, 1923 outside of the Polo Grounds. Inside heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey makes quick work of the Wild Bull of the Pampas, Luis Firpo. Jim asks Blackie about an underworld hoodlum who Blackie turns out to know well. Jim confides to Blackie about the pressure being put on him by some of the crooked players in town and Blackie distinguishes himself by insisting Jim stay honest and keep up the fight. “You’re the one guy that’s on the level,” Blackie says, “and that’s what pays off in the end.”

Manhattan Melodrama is about the love and brotherhood of these two lifelong friends. The trouble-making kid who grew up to be a professional gambler, one of the top underworld figures in New York, and the studious and moralistic lover of the law, who we watch ride his degree to District Attorney and eventually Governor of the state. Blackie respects no law, but he does respect Jim, so he remains loyal, even to his own detriment. When Blackie’s girlfriend, Eleanor (Loy), leaves him for Jim, the anger that Blackie would have simmered to a boiling rage against any other man, quickly dissipates to a warm and sincere smile towards his friend. Jim gets the girl and Blackie moves on, though it’s soon revealed that all of his expected anger has been kept in reserve, put to use against a gambler who doesn’t pay his debts. Blackie knows he’s not good enough to get where he wants by playing by the rules, but he believes entirely in Jim, and so he works within a set of rules that keeps Jim clean, even when Blackie otherwise fights dirty.

While people remember Manhattan Melodrama for being Powell and Loy’s first teaming, the movie is really all about Powell and Gable with Loy’s character bridging their two different outlooks.

As the film progresses it becomes hard to fathom Loy’s Eleanor ever having been in love with Blackie, as she is never really presented as anything approaching the stereotypical gangster’s moll. Eleanor is dissatisfied with Blackie’s lifestyle from the time of her first scene, when she complains about his having won a yacht at his gaming tables. She begs him, “Blackie, get out of this. Take me out of this.” But that will never happen. Blackie’s path has been set since boyhood. Their relationship is doomed the moment Blackie sends Eleanor in his place to meet Jim.

“My first scene with Bill [Powell], a night shot on the back lot, happened before we’d even met,” Loy wrote. “I opened the car door, jumped in, and landed smack on William Powell’s lap” (87-88). Jim has no idea who she is and is ready to toss Eleanor from the car after she jokes that she’s only there to cause a scandal, but the mention of Blackie’s name calms the waters and they wind up spending the entire night on the town together. By morning they’re in love, but Jim pulls away when Eleanor leans in for him to kiss her. A line is drawn—she’s Blackie’s girl—but she’s all Jim’s when she bumps into him that New Year’s Eve and tells him she hasn’t seen Blackie since that night they had met.

Eleanor passes Blackie information that leads to his taking action that puts him on trial for his life. As district attorney, Jim is prosecutor on Blackie’s case. Even backed into this kind of corner, Blackie’s love of Jim is still evident. He elbows his attorney upon Jim’s entrance to the court and beams when he says, “Class. It’s written all over him.” Blackie’s case allows Jim to rail against the underworld, explaining that the era of public sympathy towards bootleggers and murderers has passed with the repeal of Prohibition. Blackie takes his medicine. Jim agonizes over his involvement, finally arranging for a car to take him to Sing Sing at the eleventh hour. Face to face it’s the man of law and order who cracks, who elevates their friendship over his principals. But his pal won’t let him. “If I can’t live the way I want, then at least let me die when I want.”

“It was late yesterday when I received undercover information that Dillinger would attend the movie ‘Manhattan Melodrama,’ at the Biograph Theatre,” Mr. Purvis described the events. “I hurriedly made arrangements to surround the theatre with picked men from among my investigators …

“Dillinger gave one hunted look about him and attempted to run up an alley, where several of my men were waiting. As he ran, he drew an automatic pistol from his pocket … As his hand came up with the gun in it, several shots were fired by my men before he could fire. He dropped, fatally wounded” (Dillinger).

Manhattan Melodrama was a hit before John Dillinger dropped to the pavement. Photoplay magazine listed Gable and Powell among their best performances of the month, and included the film alongside titles such as Tarzan and His Mate, Little Miss Marker, and Twentieth Century as among the best pictures of that month. Before May was out moviegoers could see Powell and Loy in their second effort together, The Thin Man, also directed by W.S. Van Dyke. Gable, who had already starred in It Happened One Night earlier that year, was well on his way to being deemed “King of Hollywood.”

The gangster film was flipped upside-down beginning with Production Code enforcement. As “Pretty Boy” Floyd, “Baby Face” Nelson, “Ma” Barker, and other criminals met their fate, movies such as ‘G’ Men (1935) now pictured crime from the perspective of the lawman. Angels with Dirty Faces offered two main characters very similar to those of Manhattan Melodrama, but by 1938 the figure of law and order offered no death row compromise. As that later film showed the genre was different, but it had certainly survived.

Manhattan Melodrama is one of five classics found on the 2007 Warner Home Video collection Myrna Loy and William Powell Collection. The other pairings in this non-Thin Man set are Evelyn Prentice and the comedies Double Wedding, I Love You Again, and Love Crazy.

This post is part of the Classic Movie Blog Association’s Spring 2015 “Fabulous Films of the ’30s” Blogathon. It’s one of 19 Blogathon posts compiled into the first CMBA eBook, available for free through Smashwords or 99¢ at Amazon

—We are working on making the eBook free on Amazon as well, but until that time all proceeds will be donated to a yet to be determined classic film preservation-related cause.

And the 19 posts inside the eBook aren’t the entire Blogathon, only about half of it! Access all “Fabulous Films of the ’30s” posts through the main CMBA site HERE.

References:

- “Dillinger Trapped By Lure of Moving Picture Depicting Gunman Career: Slaying Detailed by Federal Chief.” New York Times. 23 July 1934, 10.

- Kotsilibas-Davis, James and Myrna Loy. Myrna Loy: Being and Becoming

. New York: Knopf, 1988.

Gable is such a star that his acting ability frequently gets overlooked, but when you think of how many times he can move you you realize just how great we was. Great co-stars always made him step it up, and he couldn’t do better than Powell and Loy. Very well done post. I enjoyed it tremendously and kind of wish I had the movie at my fingertips right now.

I am ashamed to say that it took me years to truly appreciate Clark Gable as an actor, but so happy I reached that point. “Blackie” breaks my heart. I really enjoyed your look at the picture as a whole as I haven’t seen it in a while and your perspective is always illuminating.

I agree with Marsha re: Gable’s acting. He’s often dismissed as a “real” actor, but I think he had many, many good scenes over his career.

I can’t believe I haven’t seen this one, and it’s an important film to see for all the reasons you mentioned (the John Dillinger “connection”, the 1st Powell/Loy teaming, etc.) A great pick for the blogathon!

Wonderful review! Thank you for mentioning James Wong Howe’s work–it’s stunning in this movie. What a great choice for the blogathon, too! I’d always heard rumors that this was the Dillinger movie, but thanks for fleshing that out.

“You and I must have a good wrestle some day!” says Loy to Powell on their first meeting. And did they!

Great review. This is a wonderful movie in itself, but the little asides are interesting too. John Dillinger’s take down, the first pairing of the greatest team in the movies and the only movie with Powell and Gable. They were great together and I would’ve loved to have seen them in another movie or two. William Powell’s emotion and agony while saying good-bye to Blackie was so touching and Gable’s seeming nonchalance is great. Powell and Loy, of course were just as endearing as they always would be.