Society woman Alice Morrison (Kay Francis) begs downtrodden stool pigeon boyfriend Stephen Lucarno (Paul Lukas) not to disgrace himself to save an innocent woman: “Even if she’s innocent this time, I’ll bet she hasn’t been before and won’t be again.”

This is what happens when you jump your contract, Kay. Paramount casts you as the cynic and gets the audience to root against you in favor of Judith Wood, the former Helen Johnson, who despite third billing is actually the leading lady in The Vice Squad. Not only that, but you get a lot less camera time than perennial bit and supporting player William B. Davidson and already forgotten silent film actor Rockcliffe Fellowes, making this a curious entry for Kay Francis fans who don’t know what’s going on with you off the screen. Luckily Warner’s 1931 Paramount talent raid was well publicized when it happened, but Kay Francis had to finish out her contract before joining William Powell, the actor who Paramount had originally planned to star in The Vice Squad, at their new studio. Instead Francis settles for modeling a couple of stunning gowns and looking sexy under the shadows in a nightgown while uttering all the wrong things to Powell’s replacement, Paul Lukas. “You act as though you’re in love with that girl,” Francis’s Alice says of Madeleine (Wood), the young woman who Stephen (Lukas) has inadvertently helped the police set-up on a vagrancy charge. Her Alice is the woman spurned by Lukas’s character, and not just once: Alice’s current desperation comes after Stephen returns to her life two years after he’d first run out on her.

All of this rejection prods Alice into asking the same questions about Madeleine that skeptical members of the movie crowd would have found themselves asking: “What if she is what they think? You suppose any other kind of girl is going to stay all night in a man’s room?”

Well, Alice, there were some extenuating circumstances to that last bit, so I can understand why you’re puzzled, jealous even. But you don’t know Madeleine Hunt (Wood), an aspiring novelist filled by the naiveté of youth as she soaks in life from Greenwich Village under the mistaken impression that Manhattan is so big and busy that it doesn’t have time to poke it’s nose into anyone else’s business. Madeleine made a huge mistake in standing up to crooked vice cop Mather (Fellowes) after he’s decided she’s a prostitute—but a pretty enough prostitute to leave alone if she’s willing to have some fun. Young Madeleine is outraged by Mather’s crude come-on and smacks him across his face after escaping a corner he’s backed her into. Mather is a completely vile character, but to play devil’s advocate, the situation sets itself up so that you can at least understand why Mather would jump to the wrong conclusion about our young innocent.

Madeleine has just left Stephen’s apartment. Stephen is barely an acquaintance. From her perspective he’s a mysterious though kindhearted drunk who’s saved her from barroom mashers and maulers a couple of times already. She’s returned the favor by escorting him home safely and volunteering to babysit him after the doctor she had fetched says Stephen needs someone to watch over him for a couple of days. But Madeleine and Stephen don’t even know each other’s names, and that sparks Madeleine’s trouble with Mather.

After Stephen’s illness keeps him absent from duty for a couple of days, Mather comes looking for him and passes Madeleine in the hallway outside of Stephen’s apartment. When Mather stops to ask Madeleine if she knows where Stephen lives, she doesn’t recognize her new friend’s name, but does respond to his description. She tries to keep Mather from bothering Stephen by telling him that he’s sick and she’s been taking care of him. Mather then jumps to his naturally filthy conclusions, flashes his badge, and tells Madeleine, “You’ve seen plenty of those before.” He demands her name and address, then calls her “a hot number” and backs her into the corner. “It would pay you to play ball with me, sister—in your business.” That’s when she smacks him and gets the hell out of there.

Mather doesn’t take that smack well. He already has Stephen under his thumb, so when Stephen fails to recognize Madeleine’s address, Mather decides to use him for revenge.

Mather hooked Stephen at the beginning of the movie.

Stephen was a diplomat, on his way to a ball to join his impatient fiancée Alice (Francis). He’s parked with the ambassador’s wife (Juliette Compton), trying to conclude their affair before her husband—his boss—discovers what they’ve been up to. One of Mather’s vice squad underlings pulls up alongside them and accuses the pair of engaging in indecent behavior on the side of the road. When they refuse to give him their names, the officer walks to the front of the car to take down their license number. Hoping to avoid a scandal, Stephen gets out of the car to reason with the officer, but his boss’s wife speeds over the policeman and keeps on driving. Stephen is left alone standing over a dead body.

It looks bleak for Stephen when Mather arrives and takes him into custody. After Stephen identifies himself as a member of a foreign embassy, Mather dodges any possible complications to his arrest by consenting to swing by the ball so Stephen can make his excuses in person to Alice and her brother, Tom Morrison (Davidson), a magistrate. Mather is impressed by the crowd inside and decides that Stephen could be useful to him because he “knows a lot of fancy dames.”

Stephen protects the ambassador’s wife and avoids taking on the murder charge himself by becoming a stool pigeon for Mather.

Two years pass and the once respectable foreign diplomat has turned into a self-loathing alcoholic. His work is simple though. Mather sends him up to a girl’s apartment and gives him about ten minutes to signal him on the street below. The woman doesn’t know who Stephen is, but lets him in after he says that Eddie sent him. Eddie is probably her pimp, perhaps another customer. Recognition of Eddie’s name is all that is required to conclude that this woman, Miss Thomas, is a prostitute. Stephen goes to Miss Thomas’s window and flicks his cigarette out. Mather and his men rush in and Miss Thomas soon finds herself in woman’s court responding to charges of “vagrancy.”

Guilt-ridden Stephen also comes to court, hovering in the back of the courtroom as his old friend, Tom Morrison, presides over a slew of vagrancy cases. The trashy looking women provide evasive answers to questioning and, yes, they’re all intended to be prostitutes. Frustrated by the lack of witnesses Tom asks, “Why is it, Officer, that in these cases nobody ever seems to know who the men were that are found in these women’s rooms? And why aren’t these men ever brought into court?”

When Miss Thomas takes the stand she catches the Judge’s attention by suggesting her accuser was a plant. “This court wouldn’t think of convicting anybody where a stool pigeon was concerned,” Tom says, but he’s left little choice when the plant, or unknown man, cannot be produced by the defense.

Stephen chooses that moment to exit the courtroom, but Miss Thomas spots him. Tom sends the bailiff to retrieve the man Miss Thomas has seen, a man with a cane, and is stunned when Stephen is brought before him. “You’ve made a silly mistake, my girl,” Tom says before recessing court for a moment to catch up with his old friend in chambers.

This sends Stephen on the bender that brings him into closer contact with Madeleine and her friend, Josie, a wisecracking artist’s model. After Madeleine nurses Stephen back to health he sends her on her way because he’s so ashamed of what he is. Unfortunately, this is the moment that he sends her directly into Mather’s clutches. The following night Stephen is back to work when Mather sends him up to Madeleine’s room. They’re both shocked to see one another but Stephen recovers enough to claim he just wanted to stop by and thank Madeleine once more. He then excuses himself and returns to Mather at ground level.

“It’s a mistake,” Stephen tells the vice cop about Madeleine. “No evidence. Couldn’t get any.”

Mather is uncharacteristically reasonable and sends Stephen on his way. Once Stephen is out of sight Mather turns to his men and says, “Now we crash the joint.” His men are reluctant, but they follow. Madeleine is locked up and the only way she can escape a ninety-day jail sentence is for Stephen to expose himself for what he is. “If she goes up, she may get to be just what they say she is now,” Madeleine’s friend Josie tells Stephen, who’s left to wrestle his conscience and Alice’s opposition to his exposing himself. Complicating matters, Alice’s brother Tom is scheduled to be the presiding magistrate over Madeleine’s case, giving Stephen one more reason not to expose himself.

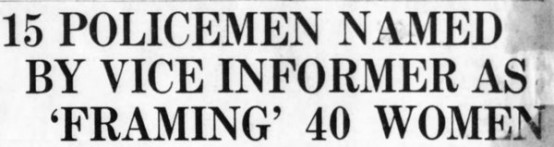

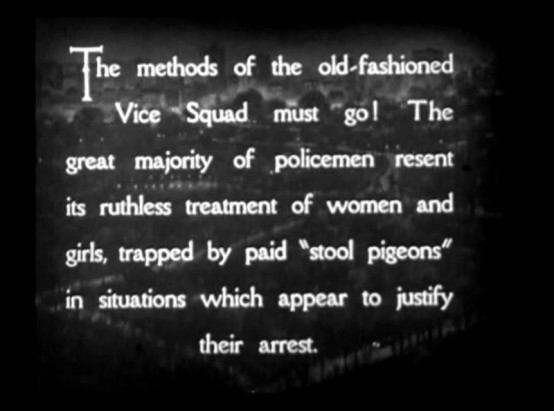

This sounds outrageous, and it is, but The Vice Squad was ripped right out of the day’s headlines.

“I worked for every inspector in town,” Chile Mapocha Acuna told the Seabury Commission prosecutor. Acuna said he was the unknown man in approximately 150 Vice Squad arrests during the first eight months of 1929. To rake any politeness or euphemism out of the early thirties newspaper reports, Acuna claimed that he posed as a john, a customer for prostitutes, at the police’s behest approximately 150 times.

“If it was an ordinary case I got $5,” Acuna said. “If it was in a nice hotel, or we arrested somebody of means, I got $10.” It was the small end of a vice racket that began with stool pigeons like Acuna and led to bondsmen, lawyers, and police, who conspired to frame working-class women on “vagrancy” charges that could be made to disappear with a large enough payoff. To give an idea of the scale of this operation, John Weston, assistant district attorney at the Manhattan Women’s Court for eight years, admitted to pocketing over $20,000 in bribes during that time.

In addition to bribing the accused, over fifty young women wound up spending time in prison after evidence was concocted out of thin air against them thanks to the presence of “unknown men,” stool pigeons like Acuna, who said police asked him to do this “not for the purpose of making arrests but making money out of them.”

Acuna explained that he couldn’t coerce any proof of wrongdoing in thirty or forty of the cases he had worked, but that it didn’t matter to his police contacts: the women were arrested anyway and Acuna was paid for living up to his job as unknown man. Like Stephen said in The Vice Squad: “No evidence. Couldn’t get any.”

“New York’s vice inquiry has been borrowed from freely in the creation of [writer Oliver H.P.] Garrett’s story,” Variety said in its review of The Vice Squad. “Many of the details are faithful copies. Chile Acuna’s exhibition of amazing memory is reproduced in the next-to-closing court scene … Lukas identifies the officers in quick succession, even mentioning the names of the some of the cases he was concerned in, like Acuna did before [prosecutor] Kresel.”

Paramount didn’t spread the vice around as much as the Seabury Commission. The dirty business in The Vice Squad is tied only to Mather and those few otherwise extraneous officers that Stephen identifies in the scene described above. On more than one occasion Mather mentions the trouble he could get into with his superior officers if his methods were exposed. The real-life Seabury inquiry into corruption extended beyond the Magistrate’s Courts to the Manhattan District Attorney’s office before ultimately disgracing popular Mayor Jimmy Walker, who resigned his office before official charges could be levied. The Vice Squad had come and gone from theaters by that time.

Directed by John Cromwell from Garrett’s story, The Vice Squad runs a well-paced 81-minutes with several believable twists and turns applied to Stephen and Madeleine along the way. Comparing it to the early Seabury Commission newspaper clippings, the movie does a good job of dramatizing the actual happenings as reported at that time.

Casting is a bit distracting. You expect more from Kay Francis and less from a host of others: Judith Wood, Esther Howard, William B. Davidson, and Rockcliffe Fellowes each figure in the movie more than Francis does, but all are up to their assigned tasks. The presence of someone like Francis in opposition to Wood in a much sunnier role does create some romantic intrigue. Discovering that William Powell was planned for the Paul Lukas role is disappointing, though before I was aware of that I thought Fredric March would have been ideal as Stephen. Lukas worked for me though, even if his accent is a bit too thick at times.

No dull spots in this entertaining 1931 talkie that turned out to be truer-to-life than I had first imagined.

The Vice Squad has never been released to home video.

That is a fascinating story behind the movie. When I was reading the synopsis, I thought, “This sounds a little far-fetched.” Shows you how much I know!

Another post I assumed would be quick and easy, and suddenly I find myself buried in research and absorbed by fact! Thanks for reading it through, interesting little slice of history, I thought.