Made as one thing, released and promoted as another, The Widow from Chicago is the story of the unlikely romance that brews from a woman’s infiltration of the New York underworld in search of vengeance.

It really has nothing to do with any of this:

Alice White stars as Polly, who is neither a widow, nor from Chicago, but wants the New York hoods who killed her policeman brother to think she’s both. Polly’s brother Jimmy (Harold Goodwin) poses as Chicago gangster “Swifty” Dorgan, after he and another detective chase the real Swifty off a train that was headed into New York. A flashback showing Swifty’s dive off the train reveals him as Neil Hamilton, a big enough star to clue us in from the start that Swifty survives his hasty exit, no matter what Jimmy believes. While Hamilton alone was—and is—enough for audiences to sniff out survival, the same can’t be said for Harold Goodwin, and, sure enough, Goodwin’s Jimmy is rubbed out before the movie is six-minutes old. There’s a small surprise when an image of the police report of Jimmy’s death is followed by another of sister Polly’s name on a missing persons report, but that’s soon alleviated by Polly’s attention-grabbing entrance into the Crystal Dance Palace.

The Widow from Chicago was hatched as the latest vehicle for Alice White, one of First National’s few remaining stars at this time, but by the time the film was released to theaters in November 1930 it was Edward G. Robinson who was getting the push from Warner Bros.-First National. Robinson’s Dominick is an underworld beer baron who runs his empire from an office located inside of the Crystal Dance Palace. He’s the kingpin who the real Swifty was coming from Chicago to meet. It’s a natural role for Robinson, a warm-up to his next film, Little Caesar, though nobody was thinking about that when The Widow from Chicago was first announced. At that point First National claimed to be leaning another way while trying to cast Dominick:

Above text from Variety, April 2, 1930, page 2. It reads: “Scarface Al as Actor. Hollywood, April 1. It is seriously stated by First National an offer to ‘Scarface Al’ Capone, Chicago beer baron, to appear in ‘Widow from Chicago,’ Alice White’s next picture, has been made. Figure it good publicity.” And below, you can make out the text, but it was clipped from Jay D. Bee’s “Movie Rambling” column in the Ogden Standard Examiner, April 6, 1930.

The Variety clipping smells the joke. The other clipping smells a rat. In any case, Film Daily began mentioning Robinson in the Dominick role before April was out.

We meet Dominick as he’s confronted by Johnston (Lee Shumway), a rival who does have armed underlings—“You tell those men to get their hands off the Roman candles,” Robinson orders—yet is expected to rely on Dominick’s liquor supply at his restaurant. If you judge the figures of Dominick and Johnston by their surroundings, it’s no contest: Johnston’s restaurant is luxurious and boasts wealthy and influential patrons, while Dominick’s dance hall is a wide-open space filled with dames offering up dances at the the typical ten cents per twirl across the floor. But equals they are as Dominick later tells Polly: “Him and me are in the same business, and there isn’t room for both of us.”

Yes, Polly has sashayed her way into the Crystal Dance Palace, her appearance causing the jaws to drop on Dominick’s two henchman, Slug (Frank McHugh) and Mullins (Brooks Benedict), who pay no heed to their boss’s advice: “You guys will learn—if you live long enough—women and business don’t mix.”

Polly sets Slug aside with a wisecrack before sidling up to Mullins, who she has correctly appraised as Dominick’s right hand. She feigns ignorance of Dominick and even begins to mock him from just a table away, setting Mullins on edge. “He’s so dramatic,” Polly says of Dominick. “Look at him. Looks like the heavy in Way Down East.”

Dominick leaps from his table to confront Polly, who cracks wise until he orders her out to the street. On her way past him, Polly asks, “Did you ever hear of Swifty Dorgan?” It works. She has Dominick’s attention. Polly claims that she’s Swifty’s widow, even pulling out a letter to Swifty in Dominick’s own hand to prove the point. Dominick bites, fires one of the girls, and the next scene begins with a large poster picturing Palpitating Polly Dorgan, the Crystal Dance Club’s newest attraction. Polly is in.

Polly angles her way into Dominick’s confidence and he soon makes plans for her to infiltrate rival Johnston’s restaurant as his spy. Dominick is using her for his final payoff, while giving Polly the exact leverage she craves to crush Dominick and gain revenge for the death of her brother. Both are tossed a curve when Slug knocks on Dominick’s office door to announce Swifty Dorgan’s arrival.

“Your wife’s here,” Slug had told Swifty when he first spotted him, congratulating his old pal on his good taste while ogling the poster of Polly in front of them. Swifty plays along. He’s introduced to Dominick, who takes him into his office to reunite him with his wife: Polly springs from her chair and embraces Swifty, and Swifty keeps playing along. Dominick, satisfied that everything is on the up and up, takes to calling Polly “Mrs. Dorgan,” and excuses the couple so they can settle back into their lives together. On his way out Dominick tells Polly to forget about Johnston, an assignment he later gives to Swifty instead.

When they’re alone at Polly’s apartment, Swifty demands, “Who you trying to take? Dominick?”

“Who else,” Polly replies.

Swifty takes off his hat to stay awhile and backs a nervous Polly into her bedroom where he wraps his arms around her. She struggles, but he only stops from the surprise of spotting the briefcase he’d carried the night he leapt from the train. It’s a very distinctive bag decorated by two large swastikas, which were still thought of as a symbol of luck at the time of this movie. No doubt it’s his, but what’s it doing in the hands of this stranger posing as his wife? Swifty demands an explanation, and Polly spills the truth about her brother. Her story causes Swifty to have second thoughts about exposing Polly to Dominick. He keeps on playing along, and as they act out their parts for Dominick, Swifty and Polly begin to fall for each other.

The Widow from Chicago breezes along, its hour-plus running time never giving it a moment to pause for anything too inconsequential. Polly, despite her growing feelings for Swifty, never forgets why she’s associating with gangsters in the first place, and Dominick’s vendetta against Johnston eventually allows her to take her revenge against the man who ordered her brother’s death. Dominick then discovers Polly’s duplicity, but it’s too late, and he’s soon involved in a gun battle with the police over the darkened floor of his Dance Palace.

The film provides a small preview of Robinson’s coming iconic role in Little Caesar, a part that also shot him to the top of First National’s billing for The Widow from Chicago within a few months of its release. Robinson’s ascent coincided with the end of Alice White’s run at First National. Her contract was not renewed after her next feature, The Naughty Flirt. White’s stardom, a phenomenon of the early talkies, had run its course, and First National broke free before it came time to pay White any serious money.

Not counting brother Jimmy’s rub out at the start of the film, the violence of The Widow from Chicago never really goes beyond Robinson. And that violence is more anger and attitude: he doesn’t even carry a gun, though he springs across the room to retrieve one from his desk a couple of times. During the middle of the movie he’s almost like extra flavor in a film that becomes what it was meant to be, an Alice White romantic vehicle.

In the end, The Widow from Chicago is an interesting cross between an Edward G. Robinson-gangster flick and an Alice White-flapper showcase, but that becomes a bit muddled for many modern viewers who know Robinson as a screen legend but only see Alice White as a curiosity. The ending reinforces this with White receiving the expected romantic sendoff, but Robinson exiting with a wisecrack rather than under a cloud of smoke.

The dialogue is better than you’d expect for 1930, though a few actors do seem miscast (Brooks Benedict and Neil Hamilton both seem a bit too refined for the underworld). The movie is sort of a strange passing of the torch from one phase of early talking pictures to the next, but for those of us who admire White, The Widow from Chicago is a fun example of her taking her act into unfamiliar territory to play a character with slightly more depth than usual while still exuding her bubbly personality.

The Widow from Chicago was released as a manufactured-on-demand DVD-R by Warner Archive in 2016.

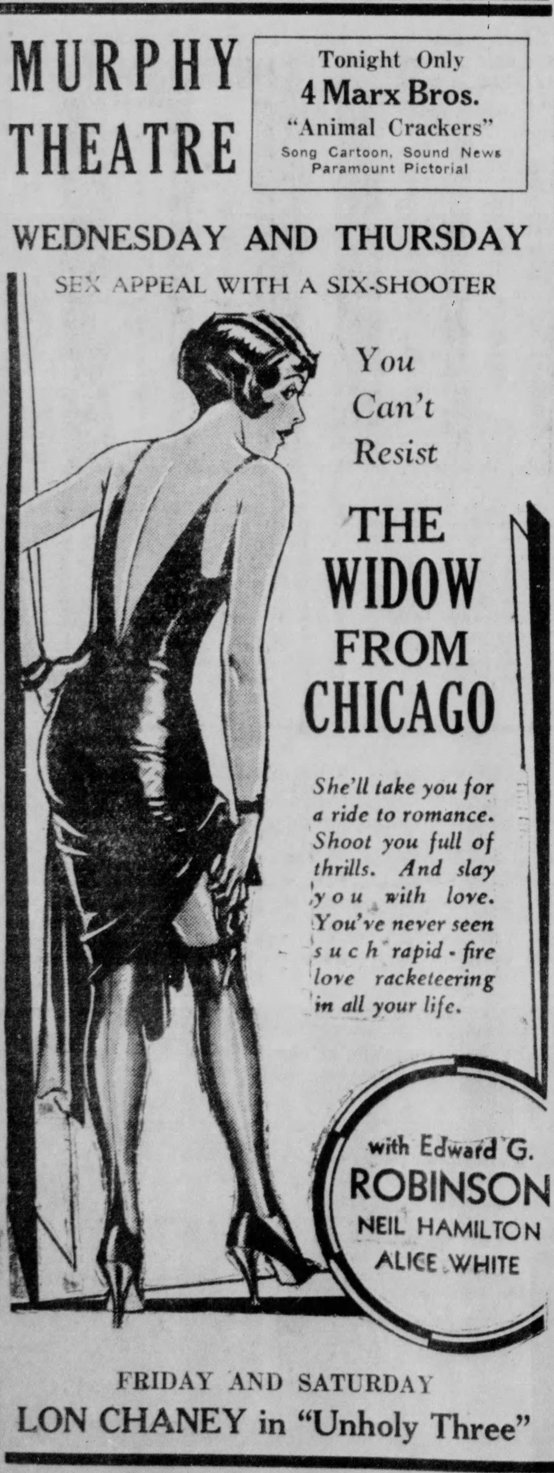

Above: From the Wilmington Daily News-Journal (Ohio), November 25, 1930, page 2.

Excellent review! Was wondering about the swastika’s on the briefcase since this was BEFORE Hitler came into power…. thanks for explaining. Despite being short of stature (like Cagney), Edward G. Robinson’s screen presence looms large. Alice White is pretty, per usual. Love gangster films made while Prohibition was still in effect, such as this & ‘The Public Enemy’, etc…

Thank you! Yes, the swastikas are a little shocking for the modern viewer, definitely needed explaining! I caught most of Broadway Babies (1929) with Alice White early this morning, not expecting much since it was such an early title—sure enough, she’s pretty rough there, but her personality shines through so well that it’s not hard to see why she was such a big star in the very early talkies. Agreed, love gangster movies, especially the early ones.