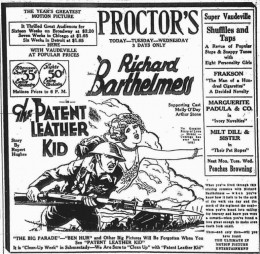

The Patent Leather Kid launched a successful comeback for Richard Barthelmess, whose career had been on the wane since Tol’able David in 1921. The Patent Leather Kid was a hit and provided Barthelmess with one of his two Best Actor nominations at the inaugural Academy Awards of 1929. Emil Jannings won that Award and Barthelmess, who came back a couple of more times in the 1930s, would never receive another nomination. But his success in The Patent Leather Kid assured Barthelmess strong leading roles at the end of the silent era and eased his transition into the new talking pictures, even after the flood of Broadway imports caused so much turmoil for formerly established silent screen stars.

The Patent Leather Kid launched a successful comeback for Richard Barthelmess, whose career had been on the wane since Tol’able David in 1921. The Patent Leather Kid was a hit and provided Barthelmess with one of his two Best Actor nominations at the inaugural Academy Awards of 1929. Emil Jannings won that Award and Barthelmess, who came back a couple of more times in the 1930s, would never receive another nomination. But his success in The Patent Leather Kid assured Barthelmess strong leading roles at the end of the silent era and eased his transition into the new talking pictures, even after the flood of Broadway imports caused so much turmoil for formerly established silent screen stars.

The Patent Leather Kid is best described as a boxing-war-romance with success most likely resulting from the off-screen popularity of the first element and the on-screen popularity recently achieved by The Big Parade (1925) in blending the other two genres. For all of the kind words lauded upon The Patent Leather Kid by contemporary viewers and fans, The Big Parade bests it as a romance and is far superior as a war movie. That leaves the opening sporting half of The Patent Leather Kid to distinguish itself, but today the boxing story is solid at best. Today, that is. All portions of The Patent Leather Kid fared better in 1927, but were so predictable by the time that I got to it that I jotted down several bits of action in my notes before they actually occurred on screen.

But in the afterglow of The Big Parade and with its theatrical release mere weeks ahead of the big Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney rematch, it isn’t very hard to see the appeal from a 1927 perspective. Especially when the lead character’s story so closely mirrored former heavyweight champ Dempsey’s own biography up until the time slacker allegations caught up with him after the war. The difference between fact and film is that Dempsey kept on boxing through the war and the following decade, while the Patent Leather Kid reports to Camp Dix after he is drafted and from there ships off to France as a soldier. Released during the height of boxing’s Golden Age, it isn’t hard to imagine The Patent Leather Kid being received then as Rocky (1976) was received during another exciting time in boxing history, the mid-70s.

The performances in The Patent Leather Kid top the story and the surprising thing is that there’s someone better than the Academy Award-nominated Barthelmess.

Seventeen-year-old Molly O’Day, who had cut her teeth the past couple of years in Hal Roach comedy shorts, was selected for the role of wisecracking nightclub dancer Curley Callahan after Dorothy Mackaill’s temperament cost her the part. O’Day turns in a performance well beyond her years, benefiting from some of the best comedy touches in the movie and surviving a patriotic fervor that threatens to turn Curley into a nag, while providing a few breathless bits of romance and ably handling her part in the film’s horrifying climax at a makeshift front line hospital. I suspect had the Academy Awards already been established for a decade or two by the time of The Patent Leather Kid, Molly O’Day would have been the one receiving a nomination. She did receive recognition the following year in being named a WAMPAS Baby Star, but further advancement was said to be plagued by weight issues. O’Day disappeared from the screen once and for all shortly after her first marriage to comedian Jack Durant.

Based on a short story by Rupert Hughes that originally appeared in the February 1926 edition of Cosmopolitan magazine, The Patent Leather Kid was a film from First National Pictures, produced and directed by Alfred Santell.

It’s the story of an unpopular yet talented (“Even if he is a dude—the Kid can fight”) boxer named the Patent Leather Kid (Richard Barthelmess). The film opens at New York’s East Side Boxing Arena in 1917, where the Kid seems more concerned with his hair than anything else as he readies for his fight against Battling Sharkey. Inside the arena the Kid receives final instructions from his manager, the mercenary Jake Stuke (Matthew Betz); his sidekick trainer, Puffy Kinch (Arthur Stone); and his supportive sparring partner, Molasses (Raymond Turner). Outside the crowd is buzzing as they push past each other into the arena. Curley Callahan (Molly O’Day) sasses her cab driver before being escorted into the arena by her date, Hugo Breen (Lawford Davidson), described by the intertitles as a Fifth Avenue big shot, “polished, polite and not too particular.”

These six are the only characters of any substance throughout all of The Patent Leather Kid (My copy runs 129 minutes, but it is listed at 150 minutes on the IMDb and other websites). Barthelmess is the star and O’Day his love interest. Davidson’s character provides romantic tension and, later on, is ironically Barthelmess’ superior officer. Stone’s Puffy is the Kid’s loyal sidekick at ringside and in the trenches, while Betz’s character doesn’t see the Kid as anything more than a meal ticket. His Stuke aligns himself against O’Day’s Curley from the start and does his best to convince the Kid that he’d be a fool to enlist, while Curley presses him to be a soldier. African-American actor Turner plays Molasses, who gets some small bits for comedy relief, but is also the first of the Kid’s group to enlist for battle. Molasses winds up becoming more decorated than any soldier you’ve ever seen, but, of course, that’s because he shoots dice better than any of the other soldiers in France.

The most interesting parts of the film for Barthelmess as the Kid come during the relatively brief period when he is condemned as a war-time slacker. On Good Friday, 1917, when the headlines announce that war has been declared and the paper is otherwise crammed with war news, the Kid is dismayed by a small piece in the sports section suggesting that his next opponent, Skeeter, will knock him flat. The war isn’t even a distant thought to him at this time, just a bit of news that in no way relates to his life as a pug. Curley soon sets him straight, but the Kid’s manager, Stuke, tells him he’d be a fool to join up. What if his hands were shot off or if poison gas burnt his eyes out? The Kid is plainly upset by all of this talk and is thrown for a further loop when Curley accepts a soldier’s invitation to dance. The Kid tries to stop her, but Curley tells him, “If you want to fight, get a uniform.”

By the time of the Skeeter fight it seems that everyone but the Kid has become caught up in the patriotic fervor of the war. Outside of the arena military men rally and disdainfully reference what’s happening inside the building, where two slackers are fighting for a filthy dollar. The crowd heckle the Kid inside the ring, but he does his best to beat the Skeeter once the fight is on. Suddenly, the action is interrupted as the group gathered outside of the arena play the “Star Spangled Banner” and the music filters into the building. Between the patriotic tune and the crowd’s continued heckling the Kid lets down his guard and winds up with his back on the canvas. His corner has to carry him back to the dressing room where he’s revived by smelling salts. Disoriented, the Kid asks what happened and Stuke tells him he “got patriotic and listened to the music and he knocked you cold, that’s what happened.”

Later that night the Kid arrives at Curley’s nightclub and spots her dancing with his nemesis, Hugo Breen, who’s looking spiffy in his officer’s uniform. It’s an innocent enough situation, but when Curley asks the Kid if he remembers Mr. Breen the Kid replies that he sure does: lousy with dough but afraid to fight. “Afraid to fight?” Curley says. “Where’s your soldier clothes?” That’s the final straw for the Kid, who knocks out Breen and practically starts a riot before exiting the club and hoping to catch up with his buddies, Puffy and Molasses. He finds Molasses in uniform and Puffy tells him he’s been drafted. “If they’d only fight this war with gloves,” the Kid says, adding that guns, gas, and bayonets aren’t his thing. After his pals take off, Curley finds the Kid and departs tearfully after thrusting a note in his hand explaining that she’s going to France to entertain the boys while learning how to become a nurse. Manager Stuke arrives next and hands over something he’d been keeping from the Kid for a few days: his own draft notice. The Kid is to report to Camp Dix.

Stuke is dropped from the film at this point, but the other five characters all find each other in France. Santell stages a scene where Barthelmess, Stone, and other soldiers march forward alongside several tanks, but the war action is ultimately a letdown. While The Patent Leather Kid winds down exactly as expected, with an injured Kid turning up on an operating table before newly minted nurse Curley, the final fifteen minutes or so are well played and somewhat gruesome. A too convenient happy ending wraps up the movie in the expected manner.

I hate to be hard on a movie because of what came after it, as that isn’t something any film can ever control, but I hesitate to recommend The Patent Leather Kid because so much of it feels tired and overdone. That said, you should know that it made over $1.2 million upon its release, and was a gigantic hit in its day. It also scores higher on the IMDb than it does with me, an unusual situation with the movies I choose to review, but one which means you may agree more with the majority than myself.

I recommend The Patent Leather Kid almost entirely for the sake of seeing Molly O’Day. Otherwise, it’s just too familiar.

I wasn’t impressed by it as a boxing movie, so I don’t think fight fans will find it rewarding beyond the narrow audience who’ll appreciate the (unofficial) link to Jack Dempsey’s legacy. If you’re looking for a great World War I film I’d first point you to The Big Parade every time, though if you’ve seen that one and want a similar infantry tale The Patent Leather Kid will do the trick, providing you lower expectations. But if you’re interested in checking out a young forgotten actress in her signature role, I’d tell you to have a look at Molly O’Day as Curly Callahan.

The Patent Leather Kid has never been released on home video, but as of this writing you will find DVD-R copies through a FindOldMovies search.

Cliff, this couldn’t have come at a more fortuitous time — I started writing about Molly O’Day last night! May I quote your review in the chapter?

Hi Jen,

I love bumping into a good coincidence! It’s heartening to know that at least two people were digging into Molly O’Day this week!

Sure, assuming you mean a few lines or brief excerpt.

By the way, I hope you clicked through to the post I put together while researching this, it’s all about Molly O’Day and Sally O’Neil.

Glad my post came along at the right time! And I’d love to hear more about what those chapter(s) add up to as a whole when the time comes.

Cliff

Of course! And yes, just a brief excerpt, no worries. 🙂

Thanks! I hope I didn’t sound like a jerk there, it’s just I’ve had people request to copy and paste entire reviews to their work, which is kind of horrifying that they’d think to do so (at least if they’re calling it their work).

Good luck with your project, and thanks again for the kind words about my post!

Completely understand, not jerky at all. 🙂