Following the murder of her lover, Jacqueline Fleuriot (Gladys George) returns home and her husband Bernard (Warren William), a rising attorney, refuses her pleas for help and mercy. She has cheated on him and she must go. Now.

When she threatens to fight for their son, he says, “Go ahead and fight. And you’ll spread the record of your unfaithfulness for the whole world to read. So our son can never escape it. It’s a new kind of mother love!”

There will be no such fight.

This incident incites the sad tale of Madame X and is why the story has been considered old-fashioned for a very long time. For an audience tempted to dismiss Madame X as being past its expiration date, the 1937 movie adds a wrinkle with the murder of Jacqueline’s lover. Bernard’s threat is now reinforced.

While disgrace is the threat, it is not solely the disgrace of being labeled an adulteress that keeps Jacqueline quiet in 1937. Instead, it is the disgrace of being branded the other woman in a sordid murder scandal that not only silences Jacqueline, but allows us to accept the stakes in her quest for anonymity.

“Madame X was delightfully simple and deliciously improbable.”

So wrote a critic named Alan Dale in a 1910 issue of Cosmopolitan when he reviewed one of the earliest performances of Alexandre Bisson’s play in America.

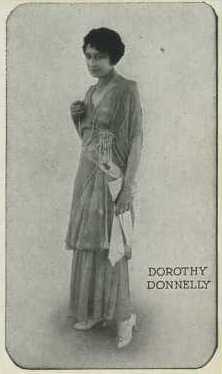

Above: Early Madame X star.

The original 1908 play by Bisson had its stage debut that same year in Paris with Jane Hading causing a sensation in the lead role. After being translated into English it was presented in London with Lena Ashwell in the lead and was a hit there as well.

Madame X made its way across the Atlantic in 1910 when Dorothy Donnelly originated the role on Broadway at the New Amsterdam Theatre. Donnelly also toured the country with the play and eventually starred in a 1916 silent film version of the story. A silent remake starring Pauline Frederick came in 1920.

The first talkie version of Madame X featured Ruth Chatterton, who was nominated for an Academy Award for her work in that 1929 release. Also nominated was director Lionel Barrymore, whose effort actually helps explain why he never made much of a mark in that profession. Barrymore probably isn’t to blame for how stage-bound and slow this earlier version is, as he only had the available technology and technique to work with, but there is no hint at any innovation towards curing those problems either. The ‘37 version relegates the ‘29 to no more than Academy Award footnote.

The first talkie version of Madame X featured Ruth Chatterton, who was nominated for an Academy Award for her work in that 1929 release. Also nominated was director Lionel Barrymore, whose effort actually helps explain why he never made much of a mark in that profession. Barrymore probably isn’t to blame for how stage-bound and slow this earlier version is, as he only had the available technology and technique to work with, but there is no hint at any innovation towards curing those problems either. The ‘37 version relegates the ‘29 to no more than Academy Award footnote.

Ruth Chatterton does impress and is especially good in the key scenes, but hers was a far more unrestrained performance than Gladys George would give eight years later. The 1929 adaptation of Madame X is just about what you would expect from such an early sound production.

Today, that 1929 adaptation starring Chatterton is paired with the 1937 Gladys George version on a two-disc Manufactured-on-Demand DVD-R set from Warner Archive.

To praise Gladys George and defend Mr. Dale’s 1910 charges of improbability (I can accept the “delicious” part), requires discussing the climax and most famed scene of the story. I’ll avoid the greater details and resulting consequences in doing so, but if you prefer to skip this section, clicking here will keep you completely spoiler-free.

After being outcast Madame Fleuriot is chased from a new life into the clutches of liquor and whatever man may have her. She disintegrates more with every change of location. She eventually finds herself back in France and on trial for murder.

Her defense attorney is her son, Raymond Fleuriot (John Beal), though Jacqueline remains ignorant of this information through most of her trial. Since this is Raymond’s first case, his father has been invited to sit on the court panel as well. Also present are Monsieur Fleuriot’s best friend, Maurice Dourel (Reginald Owen), and housekeeper, Rose (Emma Dunn), who intend to proudly beam moral support in Raymond’s direction.

Completely improbable, yes, though no more improbable than reality often is.

It is in the rendering of this courtroom scene that every version Madame X is celebrated.

First, Maurice and Rose recognize Jacqueline from the crowd. Maurice puts a hand on Rose’s arm to cut-off any exclamation of shock. Then Jacqueline’s former husband, Bernard Fleuriot, enters. After a few moments in which he does not even bother to look at the accused, it takes only a glance for him to rise in horror. Jacqueline sees Bernard’s reaction and speaks not her own defense, but a general plea for continued silence that only those who recognize her can fully understand. Her heartache is all the more intensified moments later when the prosecutor finally refers to her defense attorney by name. Only then is she aware that her son is defending her.

While the details are improbable, what each of the three key characters feels in these few moments is entirely recognizable. Raymond pours forth the greatest of empathy for a pathetic stranger that he cannot help. He puts voice to charges that unknowingly damn his own father while torturing the woman that he cannot realize is his mother. Jacqueline must continue to remain quiet, or her life has been for nothing. She stood the pain of losing her son all these years, but the situation that has arisen is just cruel. Bernard is broken by every charge that his son brings against someone he believes is an unknown offender. But Bernard is handcuffed by circumstance. The only way he can possibly make up for what he has done is to remain silent and bear the weight of his original actions forever.

If the situation is fantastic, the emotions are all too real.

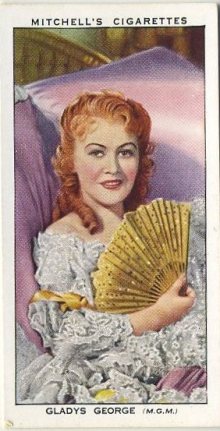

Above: MGM’s Leo presents bouquet to Gladys George. Found inside the September 29, 1937 edition of Motion Picture Daily.

Considering all of the histrionics that the part calls for, it may seem a stretch to call Gladys George’s performance understated, but she brings a very quiet, defeated posture and tone to her Jacqueline that allows the audience to not only pity her, but identify with her. Alcohol has dulled Jacqueline’s senses, but not her wits. This is most especially shown in her conversations with the devious Lerocle (Henry Daniell). Until riled to defend her silence, George’s Jacqueline often speaks in a clear yet disinterested whisper. Life has drained her voice, her words are now offered with the absolute minimum effort. It is not until exposure is threatened that she is roused to give anything more than the minimum response.

Existing biographical information about Gladys George is typically split over her date of birth. Older sources usually go with 1904, more recent sources 1900. I’m going to run with the info from her birth certificate, which lists the Evans baby girl as first child of Arthur Evans and Abbie Hazen, born September 13, 1902 in Patten, Maine.

Existing biographical information about Gladys George is typically split over her date of birth. Older sources usually go with 1904, more recent sources 1900. I’m going to run with the info from her birth certificate, which lists the Evans baby girl as first child of Arthur Evans and Abbie Hazen, born September 13, 1902 in Patten, Maine.

Her parents are usually listed as actors Arthur Evans Clare (sometimes Claire) and the Lady Clare, though I could find no reference to either of them in the press until the time of Valiant Is the Word for Carrie, when their daughter gained national attention. References to Arthur Evans Clare claim he was knighted. Some accounts attribute the honors to Queen Victoria, others to King Edward VII. He’s usually cited for military service in India, but sometimes for acting alongside Henry Irving. I’m skeptical over any title, but we’ll leave it at that, for now.

One bit I’m willing to buy, largely because it comes from a news story that refers to George’s mother by the Hazen name rather than Lady Clare, is how Gladys Evans (or Gladys Clare, if you still prefer) took the name of Gladys George. In a 1937 Screen & Radio Weekly feature purportedly written by Gladys George herself, the author recalls the name change coming after she won her first star billing in a vaudeville sketch at age ten and needed a stage name. “The person I admired more than any other person in the world, aside from my father,” she wrote, “was my mother’s father, George W. Hazen, a Boston watchmaker.” She took George from her maternal grandfather.

Gladys George debuted with her parents at age three and continued to be active in vaudeville throughout her youth. She made her Broadway debut in The Betrothal in 1918 and then played in a handful of silent films between 1919 and 1921, after making her film debut opposite Charles Ray in Red Hot Dollars (1919). She married actor Ben Erway, the first of four husbands, in 1922 and the two spent a good portion of the decade together touring vaudeville. They had a messy and public divorce in 1930 in which Gladys charged Erway with beating her and drawing a gun on her.

Above: Gladys George with first husband Ben Erway in promotion of tour. Found in The Deseret News, September 15, 1928, page 1.

Her talkie film debut came in MGM’s Straight Is the Way in 1934, but George next made her mark back on Broadway, where she starred in over five hundred performances of Personal Appearance at Henry Miller’s Theater throughout late 1934 and most of 1935. Riding the crest of that success, George next earned Hollywood praise when she was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role for her performance in Paramount’s Valiant Is the Word for Carrie (1936).

After They Gave Him a Gun (1937) with Spencer Tracy and Franchot Tone at MGM came Madame X, her last great starring role. Following Madame X, George was moved to supporting roles and she appeared in some classics. She was Madame Du Barry in MGM spectacular Marie Antoinette (1937); she had her most memorable role in support of James Cagney in The Roaring Twenties (1939); and she appeared in her most memorable movie in The Maltese Falcon (1941), but only had a small part in that classic as Miles Archer’s wife. George remained busy throughout the decade and continued appearing in movies and later on television until the time of her death in 1954.

Her death was initially suspected to be an overdose of barbiturates, but an autopsy later concluded that Gladys George had died of a cerebral hemorrhage. She was just 52, though that number is open to debate.

Her death was initially suspected to be an overdose of barbiturates, but an autopsy later concluded that Gladys George had died of a cerebral hemorrhage. She was just 52, though that number is open to debate.

The last time I tried Madame X, I put my attention in the wrong place. As part of my exploration of Warren William’s complete filmography, the movie was a total disappointment. Madame X was one of four movies that William appeared in after achieving his goal of signing with the most exclusive film company in the world, MGM, where he worked during 1937-38. William had felt taken for granted by Warner Bros., who had made him a star earlier in the decade, and after a brief period under contract to Emanuel Cohen Productions, he expected to take the next step in his career after finally landing a starring contract with MGM. The move backfired. Rather than becoming a star of Hollywood’s biggest and most glamorous productions, William’s best work at MGM came in trading barbs with Melvyn Douglas in Arsene Lupin Returns (1938). Columbia and the Lone Wolf series awaited him next.

But as I said, I had put my attention in the wrong place when I had watched Madame X from that perspective. William is actually quite effective in his few scenes of Madame X as he skillfully allows the total outrage of his first scene (“Help you? It’s all I can do not to kill you.”) to give way to an almost embarrassed obstinacy in his second scene, when he can’t even look his wife in the eye. By the time his friend Maurice (Reginald Owen) visits, he is ready to take the necessary steps to forgive Jacqueline. It is too late. He comes to accept his decision as being for the best until the climactic courtroom scene puts him face to face with Jacqueline one final time when he can say nothing to make up for his past actions.

While Warren William and other supporting cast members, including Reginald Owen, John Beal and Henry Daniell, are all effective, Gladys George is the entire reason to watch Madame X.

Hers was a highly praised performance at the time and I can only imagine it missed earning George a second consecutive Academy Award nomination because of that year’s strong pool of nominees: Barbara Stanwyck for Stella Dallas, Janet Gaynor for A Star Is Born, Greta Garbo for Camille, Irene Dunne for The Awful Truth, and Luise Rainer, who won for a second year in a row, this time for The Good Earth. Not only is Madame X a remake, it’s not even an “A” level production like the films those other actresses had appeared in. I’m sure it didn’t help matters that two of the five nominees, Camille and The Good Earth, were also from MGM.

Still, director Sam Wood elicits top performances from his entire cast in Madame X, especially Gladys George.

Both this 1937 version and the earlier 1929 adaptation of Madame X are available as a two-disc Manufactured-on-Demand DVD-R set from Warner Archive. I purchased a copy for this occasion and lifted the accompanying screen captures from their disc (which played on my desktop this time!).

Sources

- ”Actress Granted Second Divorce.” The Evening Independent 9 Oct 1930: 12. Web. Google News. 23 Aug 2014.

- Dale, Alan. “Two Kinds of Theatergoers.” Cosmpolitan May 1910: 756.

- George, Gladys. “The Men for Me. Screen and Radio Weekly. 1937: 3. Web. Old Fulton NY Postcards. 22 Aug 2014.

- ”Madame X.” The Green Book Album Jan 1910: 33.

- “Maine, Vital Records, 1670-1907 ,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1-10067-52-12?cc=1803978 : accessed 24 Aug 2014), Vital records 1892-1907 > Estey-Farrer > image 623 of 4080; citing State Board of Health, Augusta.

I liked this movie. And I thought Gladys George was marvelous in it. When watching this movie, I wasn’t aware of any larger context, of the previous plays/movies of this story. I was simply watching a movie (on TCM) and judging it of its own merits, not comparing it to anything else. And I liked it. I saw it a while ago; If I recall correctly, my rating for it was about a 7.5/10.

I really like Gladys George here. And she plays a wonderful character in “The Roaring Twenties.” (“The Maltese Falcon” may be the most famous movie she appears in, but she has a small role; I’ll always remember her for “The Roaring Twenties” and “Madame X.” And btw, I like “The Roaring Twenties” more than “The Maltese Falcon.” … I get the feeling that you don’t like “The Roaring Twenties” as much as I do; for me, it is the second-best gangster film of the ’30’s, behind only “The Public Enemy.” I noticed you haven’t even reviewed “The Roaring Twenties.” Why the hate, Cliff? You gotta give it another try; it is a wonderful movie! 🙂

S.B.R.

Our ratings are pretty close and I definitely agree, Gladys George is spectacular! No quibbles there, whatsoever.

Definitely no hate on The Roaring Twenties, I love that movie! I did mention that I love Scarface and Angels with Dirty Faces a little more in another reply to you (on that Doorway to Hell post), but that wasn’t intended as a slap to Roaring Twenties. No, if you notice, I haven’t written about any of those three, or The Public Enemy, or Little Caesar. With some exceptions, I tend to stay away from covering major titles like this, simply because I don’t have much new to say about them and, unlike many I do choose to cover, they don’t need me to champion their cause, they have their audience.

I’ll do a major classic every so often, like the Stagecoach post you bumped into last night, but it’s rare. I think I wrote that when I did because TCM was having a John Wayne day I was looking to piggy-back. I’ve covered a few of the major Universal horror films around Halloweens past as well. Maybe I should take up covering the big gangster flicks around every Valentine’s Day, it’d at least provide me an excuse.

eh, I get what you’re saying about the classics – and no doubt, it’s great that you champion the good movies that few people have heard of – but I do think you have what to add to the classics. Your reviews are longer than most, less nerdy than most, and generally better than most. I’d look forward to reading your review of any classic 🙂

Thanks, Steven. I may have to adapt that, “longer, better, less nerdy,” as a tagline 🙂

Regarding the bigger titles, I guess part of it is that they’re just less exciting for me to cover–much more fun for me to tread “undiscovered” country rather than just be another visitor to a tourist trap. That said, I’ll continue to slip in a better known title every so often. Off the top of my head, besides Stagecoach, there are titles such as Dracula and How Green Was My Valley on the site. Usually those posts are heavier on opinion, lighter on research than the obscurities, so you’d think I’d do more of them, but then I do love my research!

You SHOULD adopt that as your tagline.

I am, by any objective standard, a reasonably educated and reasonably intelligent individual, yet I can’t understand half the movie critics I read. I am talking really about what I read in books, not so much websites. In half the books that I read for movie analysis, I can’t understand half of what’s being written there cuz I guess the critic thinks he sounds more intelligent by being nerdy and making the reader strain to comprehend the profundities of the abstractions of the obscurities of the depths of the wisdom he is imparting.

I have a simple philosophy: If a reasonably intelligent reader can’t understand what an author is saying, then the AUTHOR, not the reader, is a failure. It’s the author’s job to write what a reader can understand, not what the author can.

I love movies and I love reading good writing about movies, but a very large percentage of writing about movies is absolutely impossible to comprehend. Honestly, it’s far more nerdy than the books I’ve read about paintings, which are stereotypically supposed to be the province of nerds.

Okay, that’s enough of a rant for one day. I’ve recently read some books about movies that REALLY irritated me.

But your stuff is mighty fine 🙂

Thanks again, Steven. I know what you mean and I suspect I may be more readable for you because I never went to film school, so I avoid the jargon that comes with that background, either purposefully or out of pure ignorance. My background is in literature and history, which is why I tend to concentrate on digging into backstory or source material rather than how a story is shown on the screen. I try to come from the latter angle like a regular guy watching a movie, which is exactly what I am. This perspective also explains much of my recent reply to you regarding Westerns.

I first noticed George in the one GREAT film you failed to mention here – “The Best Years of Our Lives” – where she plays “Hortense Derry” – the step-mother of Dana Andrews character, Fred Derry. Very memorable role in the few scenes she was in.

Gladys George like Gloria Swanson took the party route (albeit no jet setter) like Gloria. It aged this lovely creature in a very short time as one can notice in “The Roaring Twenties.” But, this gal had it over all the other bigger names in spades! She is my DAME and always will be!! I missed out on obtaining a press photo of her sitting on a bench outside the court room after testifying angrily on her behalf (press clipping) that she should be granted a divorce from her then husband Leonard Penn. Article dated July 19, 1944, the year of my birth and in my hometown of Long Beach Calif. where she testified. Would be nice to hear back from you.