“She’s attempting to sway this jury,” the district attorney protests. “And I must warn them, not to be influenced by the fact that she’s not only a brilliant lawyer, but a woman. A very attractive woman.”

By 1930 only 3% of U.S. women were lawyers by profession (Dumenil 116). Presumably even fewer were attractive, at least by the standards of John Remington, the D.A. played by John Halliday in Scarlet Pages.

To give Mary Bancroft–the very attractive and brilliant woman lawyer played by Elsie Ferguson–her due, she responds with tact: “I thank the district attorney for his compliments, but I will remind him that there is nothing in the statutes that prevents a woman from practicing the law.”

In the statutes, no, but as far as women had come by 1930, we have to be careful not to view a movie like Scarlet Pages with modern expectations intact. Women had just won the right to vote a decade before and only a quarter of all women were by then employed in any profession outside of the home. Here was Mary Bancroft on the screen, not only more professionally advanced than even most men in the crowd would be, but also voluntarily putting her personal life under a microscope and all but shattering her dream of achieving an even higher ambition, political office.

That’s the thing about Scarlet Pages, viewing it eighty-plus years after it was produced it seems to send mixed messages. The confident lead character is by profession and outward demeanor a fine example of the advances woman were making in the public sphere by 1930, yet she also harbors a secret which could not only destroy her career, but handcuffs her with guilt and restrains her from enjoying her private life to its fullest extent.

Above: Ferguson and Halliday. Mary Bancroft ignores the sparks to put the touch on Remington for another charitable donation.

Scarlet Pages is a tale of mother love in the tradition of Madame X, but Mary Bancroft suffers nobly in silence while holding onto her respectable reputation in professional and public life. She internalizes her guilt and uses it to drive her career forward and as impetus towards collecting money to aid organizations that protected underprivileged young women, including the very orphanage she sacrificed her newborn daughter to back in the even less enlightened times of 1911.

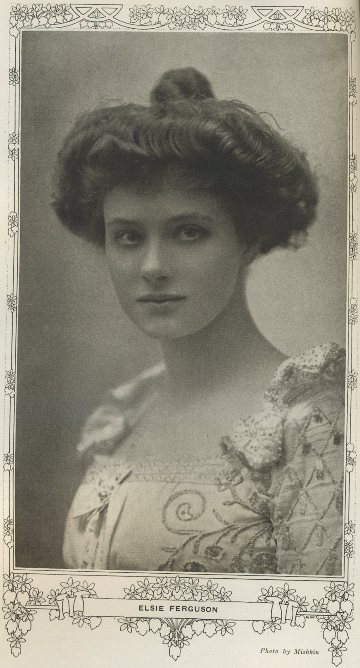

While the Mary Bancroft character provides some fascinating background to ponder, the greatest gift of Scarlet Pages is in providing the only talking film–as well as very nearly the only surviving film of any kind–featuring Elsie Ferguson, one of the greatest English-speaking stage stars during the first quarter of the Twentieth Century.

Ferguson, born 1883, began her career as a chorus girl just as the century turned when she played in the comedy The Belle of New York at New York’s own Madison Square Theatre in 1900. After deciding to become a legitimate actress Ferguson made her Broadway debut in 1903 in the musical The Girl from Kay’s and remained active on Broadway throughout the next three decades. Her greatest successes during this early period were generally thought to be 1909’s Such a Little Queen or 1914’s Outcast. After distinguishing herself as Portia in Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s production of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice in 1916, Adolph Zukor coaxed her under the Paramount Artcraft banner with a three-year movie contract at $5,000 per week. Her debut film, Barbary Sheep (1917), was directed by Maurice Tourneur, who became Ferguson’s favored director at that time. Upon completion of her contract Ferguson returned to Broadway to resume her stage career, but she came back to Paramount on a two-year, four movie deal in 1921. Under this contract she would star in Sacred and Profane Love, a title adapted from a play she had previously starred in, similar to her later experience in the movie being discussed here, Scarlet Pages. She returned to the movies for The Unknown Lover in 1925, but spent most of the decade working on the stage as she preferred. She retired from acting after appearing in the film version of Scarlet Pages, her only talking film, and split her time between homes in her favorite places, a farm in East Lyme, Connecticut and across the ocean in Paris, France. In 1934 she married for a fourth time to a wealthy husband whom she widowed in 1956. Ferguson only came out of retirement once, returning to Broadway in 1943 for Outrageous Fortune, a play authored by East Lyme neighbor Rose Franken. Ferguson never had children and with no survivors upon her death in 1961 she bequeathed her vast fortune to several animal welfare and protection centers.In Scarlet Pages we get Ferguson at age 47 playing a woman of 36. Her youth holds up a bit better than her performance which, despite a pleasant enough, though highly theatrical, speaking voice, is marred by a perpetual smile that is charming in and of itself but begins to wear after the realization that it is never going to fade. Perhaps this constant view of Ferguson’s upper teeth is what causes co-star John Halliday to look as though he has the giggles through a good portion of Scarlet Pages. This mirth actually evaporates when the pair are seated at a nightclub table to watch the Marian Nixon character perform, a single moment in the movie where they really should be enjoying themselves, yet they look like the crowd at Springtime for Hitler. They at least get a hold of themselves during the big dramatic finale, with Halliday giving an especially fine performance in this scene and Ferguson giving Lionel Barrymore something to channel during his Academy Award winning courtroom speech in A Free Soul the following the year.

The twist, obvious from the opening minutes of the movie, [SPOILER?] comes in the revelation that Mary Bancroft (Ferguson) is Nora Mason’s (Nixon) mother. Perhaps the only thing less surprising than this discovery is the stigma attached to Bancroft’s having given up her infant daughter for adoption when she was just a woman of nineteen herself.

This guilt weighs on Bancroft from the earliest moments of the movie, it is even the unspoken reason for her refusal to submit to the romantic advances of Halliday’s dashing John Remington. Bancroft, an otherwise confident and powerful woman, considers herself sullied beyond all respectability and would not presume to become involved with a man of high standing such as Remington. This seems a bit extreme even by 1930 standards for a pair of mutually attracted adults who, despite the script, are obviously on the north side of forty, but Halliday redeems himself at movie’s end by suggesting to Mary that her career in law is not only unharmed, but even enhanced by her sacrifice (even if political aspirations are shattered) and sees Scarlet Pages leaving us with hopes that our well-matched lady lawyer and district attorney may yet have a future together. Of course, such a future could very well provide Mary Bancroft with a new position as Remington’s wife, one which would presumably allow her to discard her professional career and political ambitions altogether in order to back a good man headed down that same path she had originally wished to travel herself.

For all of Scarlet Pages’ problems it did quite well in the movie theaters in 1930, seemingly surpassing any success it had had on the stage the year before. The play was panned with almost any praise being reserved for its cast, led by Ferguson with Claire Luce using the Nora Mason character as her own steppingstone to Hollywood. I assume Luce wasn’t cast in the film because of a story passed down by critic George Jean Nathan, who reported that the temperamental Ferguson once smacked Luce across the nose after Luce had captivated the crowd to a greater degree than the world famous star was willing to permit on her turf. Former Ferguson theatrical co-star Sidney Blackmer once referred to her as “The most charming person off stage you have ever seen in your life and the most difficult on,” full of temperament, but someone he said he liked nonetheless (Farley).

Two-page spread advertising Scarlet Pages in trade paper Film Daily, October 1, 1930, found through Lantern search engine. Click to enlarge.

During its stage run Scarlet Pages was typically dismissed as a creaky combination of Madame X and The Trial of Mary Dugan. Warner Bros. must have seen promise in some of the more lurid details that come out during the murder trial, which makes up the bulk of Scarlet Pages. If so, it was a correct assumption and the sophisticated story was instead marketed as a “dirty picture” by 1930 standards. Paging through the trade papers all reports for Scarlet Pages indicated big business with the title being held over for additional weeks in many cities. Advertisements stressed that this was a movie for adults only. There were even age restrictions at some theaters with Ottawa serving as a good example as to how Scarlet Pages kept its legs: When first released in Ottawa, no one under the age of eighteen was admitted to theaters, but the age restriction was lifted for its second run in the city and, according to Motion Picture News, “the high school flappers” came out in droves to see what all the commotion was about.

A Film Daily ad shows that Scarlet Pages just keeps earning. Found in the September 24, 1930 edition via Lantern search engine.

The adult content is hinted at before being talked around though never quite exactly specified. It comes out, such as it does, during the trial when circumstances cause Mary Bancroft to finally wring out of Nora Mason why she had killed her father: “… he was drunk, disgusting. And I had to listen while he tried to force me into consenting. And then he said I couldn’t blame any man for loving me.” Consenting? Consenting to what? Working for capitalist Jackson (William B. Davidson), a job with many strings attached? Partially, but he “force(d) her into consenting” that evening after storming drunk into her bedroom, and if you can’t “blame any man for loving” Nora, you couldn’t blame him either—especially since he wasn’t her real father. You weren’t slipping incest, even implied incest, past the censors any less delicately, even prior to more rigid and official enforcement of the Production Code.

Newspaper ad for Scarlet Pages–“we DO NOT recommend it for children!”– from the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, September 18, 1930, page 11.

Beyond, or perhaps in aid of, exploitation of the sensitive material in Scarlet Pages was praise for First National’s careful execution of the potentially censurable story: “Had less discretion been used here, the watchdogs of the movies would have ripped the lines out with probably a pardonable excuse,” wrote Karl Krug of the Pittsburgh Press.

In addition to fulfilling the opportunity to see Elsie Ferguson perform, highlights of Scarlet Pages come in Nixon’s nightclub performance, adorably clumsy, and the few intentional moments of comedy provided in the courtroom questioning of character actor Fred Kelsey, here an Irish-accented bouncer at Nora’s club (just what was his wife doing in the courtroom?), and the delightfully hilarious Jean Bary, a.k.a Jean Laverty, a showgirl whose legs capture the (all male) jurors’ attention and whose date-book threatens to empty the courtroom upon exposure.

I hate to say it, but Jean Bary’s few minutes on the stand as Carlotta Cortez is my favorite part of Scarlet Pages.

Marian Nixon, who I recently tabbed as underwhelming in Winner Take All (1930) with James Cagney, no doubt makes her presence felt in Scarlet Pages, but we could have done with much less. You could say that her over-the-top defiance as showgirl Nora Mason is an expert layering of the false bravado of youth onto a character who is nevertheless supposed to be sweet despite the wild associations of her occupation. That would be quite generous. The most I’ll give her is that her sullen stares throughout the trial are effective. The actress, perhaps harmed by what I take to be a startling resemblance to the far more talented Myrna Loy, proves her mediocrity in her final scenes, once the facade is dropped and she’s allowed to be the sweet, tender young girl that Nixon is supposed to excel at. She only succeeds in making us notice that by contrast Miss Ferguson is playing a touch too theatrical before the movie cameras.

Scarlet Pages is a First National production based on an original play by Samuel Shipman and John B. Hymer. The movie was directed by Ray Enright, who we last saw at the helm of the much more impressive Blondie Johnson (1933). Enright doesn’t distinguish himself with this early talkie which, given Ferguson’s presence, should have been of better overall quality, though perhaps knowing what we know of Ferguson’s temperament was the best he could get. Scarlet Pages premiered September 28, 1930, following stage predecessors Madame X and The Trial of Mary Dugan (both 1929) to the screen with a brief bang as illustrated by the contemporary advertisements on this page.

The most interesting element of Scarlet Pages is in providing Ferguson with what would have been a very strong female character in 1930, even if much of what was daring about Mary Bancroft then is tempered when applying modern standards. The scarlet of the title seems old-fashioned even by 1930 standards and judging by some of the critical response to the 1929 stage version, they thought so back then too.

I wasn’t even aware of this until putting the finishing touches on this post, but Scarlet Pages is available for purchase as a MOD (manufactured on demand) DVD-R from the Warner Archive. The screen captures from the film found on this page are from my own recording off of Turner Classic Movies which had recently played Scarlet Pages.

Cited

- Dumenil, Lynn. The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s

New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

- Farley, Jane Mary. “Leading Ladies Star in Veteran Actor’s Memory.” Milwaukee Journal 7 Apr 1960: 1. Web. Google News 16 May 2014.

- Krug, Karl. “The Show Shop.” Pittsburgh Press 20 Sep 1930: 11. Web. Google News 16 May 2014.

- Nathan, George Jean. The Theatre of the Moment Cranbury, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1970.

Leave a Reply