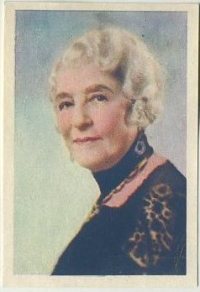

Aline MacMahon and Basil Rathbone in Kind Lady

After some quiet music over the opening credits a church choir solemnly sings “Silent Night” and all seems well for patrons settling into their theater seats in December 1935. Thanks to the popular culture specific to that era modern audiences are more likely to be shocked by what is to follow than our friends from that earlier time would have been.

I attempted to write about Kind Lady (1935) sometime in 2010 after I had first been stunned by it myself. I failed. Try as I might I could not tell you anything worthwhile about this one without ruining it for you. I still don’t intend to spoil Kind Lady for first time viewers, though I cannot write about it at any length without depriving you of the experience I enjoyed during my own first viewing. That cat is out of the bag already even if you have only read this far. Sorry.

Christmas may be the setting but Kind Lady is no Christmas movie.

Kind Lady Background

Maybe you have read Hugh Walpole and have an inkling of what is to come. Certainly more people had read the popular author in 1935 than have today when he is considered well past his expiration date. But even if mid-1930’s moviegoers had never spotted Walpole’s 1930 short story “The Silver Mask” they would have had a better idea of what was to come on the screen than we do sitting down to enjoy that same movie for the first time today. Walpole’s story had been adapted and expanded into a play titled Kind Lady by Edward Chodorov and had just enjoyed its first successful Broadway run earlier in 1935.

Chodorov changed the name of the kind lady of the short story from Sonia to Mary Herries. Walpole fans will recognize the surname as that of his best known characters from his collection of four novels comprising what is referred to as the Herries Chronicles. Walpole’s “The Silver Mask” was a short story published separately from the four main novels. The original story, which you can read in its entirety HERE, ended on a distinct down note, the Henry Abbott character, whom we shall soon meet as played by Basil Rathbone, coming out on top of Mary Herries.

The play was a hit with both critics and audiences and ran for over one hundred performances on that initial run. It was revived many times over the years, most successfully as soon as 1940 when Grace George returned as Mary Herries. MGM pounced on the opportunity to make the stage hit into a film as soon as it possibly could. 75-year-old May Robson was slated to play Mary Herries in their coming film version and was given the opportunity to test out the lead role on the West Coast in a series of live performances in October 1935.

The play flopped. Curran Theater company manager John Leary Peltret wrote Oakland Tribune journalist Wood Soanes stating that “the play has not received the support which its quality warrants and we are ending the engagement at the Curran next Saturday.” In the letter, largely excerpted to the Tribune by Soanes, Petret could not make heads nor tails of where they had gone wrong. Soanes could.He placed the blame entirely upon Robson. Despite giving a performance that he had raved over himself just a week earlier she had “for the last two decades … persisted in lending her talent to inferior plays, surrounding herself with cheap companies and, generally trading on her fame in The Rejuvenation of Aunt Mary.” Soanes admitted that Kind Lady proved Robson could still act but wrote that it would take more than one good show to restore the public’s good faith in her.

An interesting side note inside that same article adds that Hugh Walpole, author of “The Silver Mask,” had just gone to work for David O. Selznick on the screenplay for Little Lord Fauntleroy (1936). Walpole had recently worked on the script for one of Selznick’s final bits of work at MGM, David Copperfield (1935), in which he also acted a small part.

An interesting side note inside that same article adds that Hugh Walpole, author of “The Silver Mask,” had just gone to work for David O. Selznick on the screenplay for Little Lord Fauntleroy (1936). Walpole had recently worked on the script for one of Selznick’s final bits of work at MGM, David Copperfield (1935), in which he also acted a small part.

I don’t know if the Oakland Tribune story was truth as reported by Soanes or a story planted by MGM to explain away Robson’s removal from the project, but one thing is certain: May Robson does not star in Kind Lady. The part went to an actress nearly forty years younger than Robson, Aline MacMahon, who was freelancing at that time.

Aline MacMahon

After ten years on stage Aline MacMahon had made her screen debut in Five Star Final (1931) and scored again after that in support of Warren William in The Mouthpiece (1932). By September 1932 she was given a long term contract with Warner Brothers that included a stipulation granting her three months off each year to return east and be with her husband, architect Clarence S. Stein.

After ten years on stage Aline MacMahon had made her screen debut in Five Star Final (1931) and scored again after that in support of Warren William in The Mouthpiece (1932). By September 1932 she was given a long term contract with Warner Brothers that included a stipulation granting her three months off each year to return east and be with her husband, architect Clarence S. Stein.

MacMahon was lauded for supporting performances in films such as One Way Passage (1932) and Silver Dollar (1932) and stood out as the brashest of the three chorus girls in the non-musical parts of the classic musical Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933). More laurels came for MacMahon for her strong support in The Life of Jimmy Dolan (1933), Heroes for Sale (1933), and The World Changes (1933) before being elevated from featured player to star in Heat Lightning (1934).

1933 Press photo picturing Aline MacMahon, Joan Blondell and Ruby Keeler in Gold Diggers of 1933

She had already shared the screen quite a bit with fellow Warner player Guy Kibbee, but this soon turned into a near exclusive occupation with The Merry Frinks (1934), Big Hearted Herbert (1934), the more ambitious Babbitt (1934), While the Patient Slept (1935), and Mary Jane’s Pa (1935) coming in quick succession of one another. It was a bit much.

MacMahon told reporter J.M. Ruddy that “My real problem in my job has been a certain wholesomeness with which I am afflicted. Not that it isn’t–er–nice to be wholesome. But they gave me five wholesome parts, one after the other, at Warners as a result.” She was let out of her contract in June 1935 and from there freelanced at a much less hectic schedule.

MacMahon told reporter J.M. Ruddy that “My real problem in my job has been a certain wholesomeness with which I am afflicted. Not that it isn’t–er–nice to be wholesome. But they gave me five wholesome parts, one after the other, at Warners as a result.” She was let out of her contract in June 1935 and from there freelanced at a much less hectic schedule.

Prior to Kind Lady, Aline MacMahon appeared in two additional productions for MGM, the Joan Crawford vehicle, I Live My Life (1935), and as part of an impressive ensemble cast in the lofty Eugene O’Neill based Ah, Wilderness! (1935). That earlier work for the studio must have impressed as it was MacMahon who got the call for Kind Lady after Robson so badly blew her stage warm-up for the film.

Kind Lady: The Story in Brief

MacMahon plays Mary Herries, an old maid who fills her life with collecting of precious things. Her sitting room boasts paintings by El Greco and Whistler and a Ming vase. She carries a beautiful jade cigarette case. Mary Herries is quite well off.

Henry Abbott (Basil Rathbone), an unsuccessful painter, who intrigues Miss Herries by way of his knowledge of her beautiful things, is not.

After a few meetings which leave Henry Abbott’s character in serious question he brings his wife, Ada (Justine Chase), along to thank Miss Herries for the coat she’s previously gifted her. Miss Herries shrieks when Ada collapses with her baby in her arms and the woman is soon resting in a bed inside Miss Herries home. Henry Abbott also remains on the scene. Others arrive.

Miss Herries is soon a prisoner in her own home. Abbott has designs on cashing in Miss Herries’ beautiful things and makes quite a bit of progress in that area.

One of the more interesting ideas of Kind Lady, better explored in the 1951 remake, is the notion that if you label someone, in this case insane, the outside world will very easily believe you and treat the labeled party accordingly. Beyond any physical restraints Mary Herries must overcome this mental obstacle so carefully placed between her and the outside world by Abbott.

Kind Lady: Specifics and Comparisons

You might have noticed that I’ve been harping upon the ages of the actresses who’ve played Mary Herries: Grace George at 55, May Robson at 75, Aline MacMahon at 36, and later the part would be played by Ethel Barrymore at age 71. John Sturges’ 1951 screen adaptation featuring Barrymore is generally heralded as superior to the George B. Seitz directed 1935 version we’re about to discuss. I disagree. Age is one of the reasons why.

Aline MacMahon often played older than her true age. In both Silver Dollar and The World Changes she would age from young woman to elderly spinster over the course of each film. Her constant co-star Kibbee, cast often as MacMahon’s husband, was 17 years her elder. While I’d imagine MacMahon’s Mary Herries is supposed to be beyond her own 36 years I don’t think she quite pulls off Walpole’s “fifty if she was a day” description and certainly doesn’t have a hint of the white hair he described his Sonia Herries as having.

There was no white wig waiting in wardrobe for raven haired MacMahon. Her Mary Herries is certainly meant to be younger than any of the other actresses who took on the role over time. This gives the 1935 film version of Kind Lady a hint of sex that is missing in other tellings of the story.

Early in the film Mary Herries is presented with a bundle of mistletoe by a shabby woman who advises, “You know what they say, that them what buys it finds romance.” Miss Herries sister, Mrs. Weston (Doris Lloyd), is paying a Christmas Eve visit when Henry Abbott makes his own first visit, begging his way inside Miss Herries’ door for a cup of tea. There’s a glint in Mrs. Weston’s eye as she offers Abbott the hospitality of her sister’s home. After her sister departs Miss Herries and Abbott talk and it is soon revealed that Abbott has a wife. After he leaves Mary Herries tosses the mistletoe into her fireplace. The product had been misrepresented.

Mary Herries of the 1935 film had a young man in her past but lost him in the Great War. Walpole’s original Sonia Herries from the page had had opportunities to marry twice in her past but had not loved either man enough. The man she had loved had not loved her back. Walpole describes her as maternal “beyond everything else.” “Had she had a child her nature would have been fulfilled,” he wrote. “As she had not had that good fortune she had been maternal … to numbers of people who had made use of her …” It was this maternal nature that caused Herries to suffer “dreadfully from impulsive kindness.” MacMahon’s Mary Herries, after realizing handsome young Abbott is claimed by another woman, becomes a bit of a reluctant mother hen whom Abbott can easily manipulate.

Abbott had himself served in the War and so is likely about the same age as Miss Herries, or at least that of her lost love. (He may not look it here, but Rathbone is nearly seven years older than MacMahon in real life). Outside of Mary Herries’ home a man (E.E. Clive) plays Christmas songs on a portable phonograph and starts a conversation with the hunched over sidewalk artist, Henry Abbott. Abbott mentions suffering a worse Christmas than the current one in the trenches at Ypres in 1914. Henry Abbott doesn’t seem at all a bad man when we first meet him, just down and out. One of the forgotten men that the movies liked to remind 1930’s audiences about every so often.

After meeting Miss Herries and being surrounded by her beautiful things Abbott is reminded of his own misfortune. Abbott impresses Miss Herries with his knowledge of the El Greco that hangs in her sitting room, her Whistler, a Ming Horse, and explains that collecting was a former interest of his but that “now I find it very comforting to remember it when I’m standing in the bread line on the embankment.”

An interesting choice of the 1951 remake was to set the film in an earlier time, what appears from dress and setting to be the Edwardian Era just after the turn of the century. The forgotten men of the First World War would have hardly seemed relevant any longer at a time only a few years after the close of World War II and so, perhaps to up the chill factor, the later movie was moved back to even earlier times. While this added an overall darkness to the film it stripped away yet another layer that I had admired in the 1935 film.

While Basil Rathbone’s Abbott is responsible for a few somewhat puzzling statements along the way it is not until approximately halfway into 1935’s Kind Lady, perhaps a few minutes more than that even, that Abbott reveals himself for what he is.

Mary Herries’ housekeeper, Rose (Nola Luxford), hadn’t liked him from the start. “Too good looking.” says Rose, concluding that, “You’re too good looking, you’re up to something.” Mary Herries doesn’t heed Rose’s warning nor Abbott’s own subtle hints in conversation.

When Abbott shows Miss Herries his paintings he admits he isn’t very good but that there are some decent qualities in his cow picture, a Swiss scene. He explains that “In Switzerland the cow herd pipes his cows from the pasture. He plays a traditional melody that has an hypnotic effect on the cattle. That’s how he rounds them in. I thought it was rather a nice, macabre, idea.”

Miss Herries is too distracted by Abbott’s charm to notice his own appearance growing darker while he plays her similarly to his subjects in this Swiss scene.

And so when Abbott’s undernourished wife, Ada (Justine Chase), collapses in the street with their baby in her arms what choice does kind Mary Herries have but to heed the doctor’s advice and let the poor girl recover peacefully in a room in her own home? Abbott engineers the scene beautifully, it’s not as though Miss Herries had a choice, yet he’s tapped into her so deeply that she’s for a time convinced that she’s acted in the only proper way imaginable.

Rose eventually manages to convince Miss Herries that the Abbotts have taken advantage of the situation and Miss Herries asks them to leave. That’s when things take a very bad turn.

The Rest of the Cast

Basil Rathbone was already well established as a notorious screen villain by the time of Kind Lady’s release. The public had already had time to hiss him as Murdstone in David Copperfield and as Karenin, married to Garbo, in Anna Karenina earlier in 1935. Just prior to completing Kind Lady, Rathbone had finished up work as the infuriating Marquis St. Evremonde in another literary heavy hitter, A Tale of Two Cities (1935), which would more appropriately share Kind Lady’s season’s greetings to moviegoers when released later that same December.

Basil Rathbone with Greta Garbo in Anna Karenina as pictured on a 1940 A & M Wix Cinema Cavalcade Tobacco Card

From innocent enough beginnings Rathbone emerges as a terrifying Henry Abbott. Cold and calculating Rathbone’s Abbott is absolutely sure of himself every step of the way as he takes over Mary Herries’ life. His expert leadership keeps her physically under his thumb by way of his accomplices, simple minions who mostly obey Abbott’s orders while he carries out the more complicated portions of his plot.

Where Henry Abbott differs from the Basil Rathbone villains named above is that the character is exceedingly charming and even likable until his true intentions are known.

Where Henry Abbott differs from the Basil Rathbone villains named above is that the character is exceedingly charming and even likable until his true intentions are known.

Abbott’s accomplices are together a low band of miscreants who recalled bizarre film images to my mind ranging from at their most charming the loving cup scene in Freaks (1932) to their most threatening, the exceedingly odd family of the much later Spider Baby (1968).

This strange group is led by Dudley Digges as Mr. Edwards. Digges always excels when he gets to be nasty and Kind Lady is no exception. He doesn’t have his usual bad demeanor here, just all of the worst tendencies usually associated with it. His wife is played by the almost always evil, Eily Malyon, who just naturally looks as though she’d eat her young. And yours too.

Somehow daughter Aggie (Barbara Shields) survived being brought up by this pair, at least to her early teen years, and appears to be well on her own way to being the biggest psychopath in the house. After first arriving and going up to visit Ada, Mrs. Edwards scolds Aggie and asks what she’s doing with the baby. The youngster replies, “Oh, I just wanted to see how it breathes if I hold its nose and its mouth shut.” Charming.

Digges and Malyon are over the top when compared to the more nuanced performances that Keenan Wynn and Angela Lansbury give as the Edwards couple in the 1951 remake, but what they bring to the earlier movie especially works alongside the very polished Rathbone as ringleader Abbott.

Doris Lloyd plays Mary Herries’ sister, Mrs. Weston, in the 1935 film and returns in 1951 to play Rose the housekeeper. Blonde Nola Luxford from New Zealand makes for a much more common Rose in the earlier film than Lloyd does in the later one, but again, it works perhaps because Aline MacMahon is not nearly as exalted as Ethel Barrymore.

Justine Chase may not have a line as Ada, Henry Abbott’s wife, but she is one of the strangest performers in the movie. Watch for her little dance, it is truly bizarre! This part went to Betsy Blair in the 1951 remake where she’s more of a captive herself to her husband, the ringleader Henry Elstree played by Maurice Evans. Blair’s Ada may be a smarter way to present the character, but Chase’s unrestrained Ada is a lot more fun to watch!

Mary Carlisle plays Mary Herries’ niece, Phyllis, and Frank Albertson is Phyllis’ fiance, Peter Santard. Carlisle is mostly invisible and Albertson just isn’t very good. These characters are dropped from the 1951 version of the film though much of what the Albertson character does is left for the banker, played then by John Williams, to do in that later film. As for that banker, Mr. Foster, in the earlier movie, well, Donald Meek fans will have to wait awhile for him to show up.

Also appearing in 1935’s Kind Lady are Murray Kinnell as the Doctor and Frank Reicher as a Parisian art dealer.

The Endings

I’m still aiming not to spoil this for you but I do want to add that one of the few areas I found superior in the 1951 version of Kind Lady over my preferred 1935 version is the ending. The ’51 ending makes more sense and flows a lot more naturally from the story then the sloppy wind-up to the ’35 movie does. The ending to the earlier movie feels a bit rushed.

While I was unable to secure a complete copy of Edward Chodorov’s original play, I was able to read multiple summaries of the action and find its ending a little more effective than either film version. The 1951 film version retains most of what Chodorov wrote and, this will mean something if you’ve seen it, added the entire bit with the wheelchair. In the 1935 version the day is saved by a combination of characters that we aren’t very invested in to that point.

In Hugh Walpole’s original story, “The Silver Mask,” the ending focuses on the object of the title which, for some reason, is not included in either film version. Henry Abbott takes the mask, one of Sonia Herries most treasured possessions, and nails it to a wall in a place visible from Miss Herries’ bed, where she was kept ill.

“You’ll want something to look at,” he went on. “You’re too ill, I’m afraid, ever to leave this room again. So it’ll be nice for you. Something to look at.”

He went out, gently closing the door behind him.

Henry Daniell, Basil Rathbone and Maurice Evans all paid a price that Walpole’s literary Henry Abbott never had to face.

Sources

- Kabatchnik, Amnon. Blood on the Stage: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery and Detection

. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2008.

- Ruddy, J.M. “The Romance of Living: Aline MacMahon Discovers the Precious Secret of Contentment.” Oakland Tribune. 10 May 1936: 87.

- Soanes, Wood. “Curtain Calls.” Oakland Tribune. 17 Oct 1935: 15.

- Scheuer, Philip K. “A Town Called Hollywood.” San Antonio Express 23 June 1935: 21.

- Soanes, Wood. “May Robson Attains Art in Play in S.F.” Oakland Tribune 8 Oct 1935: 20.

- Walpole, Hugh. “The Silver Mask.” All Souls’ Night

. New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

[phpbaysidebar title=”Aline MacMahon on eBay” keywords=”Aline MacMahon” num=”5″ siteid=”1″ sort=”StartTimeNewest” minprice=”19″ id=”2″]

I’m very much looking forward to seeing the 1935 version of “Kind Lady” for the first time. I’ve been intrigued since catching the 1951 version a couple of years ago. I very much appreciated your thorough background and know it will add immensely to today’s viewing.

Thanks Patricia. I seem to be the only one who doesn’t refer to the ’51 version as something along the lines of “the superior 1951 version” but I really feel like that line could be adjusted to “the better known 1951 version.” I really thought the ’35 version moved from the opening to the big reveal much more effectively though I do admit up above that I liked the ending used in ’51 better.

Plus it’s Basil Rathbone!

Hope you enjoy the movie! Think it’s on right now, as a matter of fact!

I really enjoyed the movie. It had a frightening immediacy. The 50s version, as I recall, felt like it had a more leisurely approach to the material. A haunting story either way.

Very glad you liked it! That pace might be another reward of the modern setting for Kind Lady ’35.

My dear Cliff, thank you for filling me in about the ’51 version that I just saw on TCM. Frankly, I found the picture a bit frustrating…It was obvious that it was a filmed stage-play, and the plot setup was so absurd that I couldn’t buy it. All Miss Herries had to do was take one of the many, many opportunities she was given to shout “Help! I am being held prisoner in my own house!” There was certainly nothing wrong with her legs, so why sit next to the open window in the wheelchair? Ethel Barrymore looked like a stunned ox throughout the picture. I kept wanting her to get up and do something. And, if you refer to someone in the title as a “kind lady” at least an occasional sparkle is indicated. And what’s with the note to the Paris art dealer? And the signature on Abbot’s painting of his wife? And why has Abbot, who already has a dim bulb for a wife, chummed up with that bonehead Edwards? A henchman should have more than two brain cells to rub together. And Abbot’s idiotic display of Herries’ treasured cigarette case to her own banker?? Yes, I know that the picture is a “thing of it’s time.” But if Hitchcock had got hold of it he would have fixed those details and kept the essential horror/melodramatic character. I am going to, as you recommend, have a look at the ’35 version. Perhaps there’s a version where the sound has been cleaned up a bit…That is certainly my problem with movies from the early thirties. Well, thank you again for the cast info!

I am a” newly found” (haaaa, where DID the time go?) half-centurion (age 50) medical professional from Ontario, Canada. I just watched “Kind Lady”, on Turner Classic Movies and was awestruck and memorized by the entire 1935 version of this near-flawless film. There are so many messages in this script that one must dissect their entire life or an elder loved one’s life to “see” every moment of this film’s hidden messages…some may find them to be blatant rather than hidden. I MUST say that Alien McMahon brought an arrhythmia to my heart when I saw her full beauty. She is fantastically gorgeous. She is the definition of class. Her simple smile made me truly aroused and in awe. She is and was an incredible actress that I sorely just discovered this past week. I MUST see all of her films. I can say she is someone I LOVE, as an artist and, on a personal level, she reminds me of someone dear to my heart that was lost far too soon in her/our life at age 38 due to cancer. So, it is wonderful that we CAN forget our woes for a moment or an hour or so, and see some strange beautiful woman on the screen nearly 80 years ago and feel so warm in our hearts. Thank you Robert, Ben, and Mr. Turner (et.al.) for giving us such a wonderful ‘escape’ as T.C.M. (Turner Classic Movies), any time and all of the time to witness these such gems. Bob M.

Hi Bob,

Glad you found my post and even more especially glad you found Aline MacMahon. I’m of the mind that Kind Lady is her best film, as I agree with you, it’s close to perfect. Hers is definitely an exotic beauty (Irish-Russian background) and it worked against her in one regard, relegating her to character roles, but in another way it was to her advantage because, more importantly, she was such a fine character actor! Kind Lady is a rare starring role for her and, boy, does she ever nail it!

It’s comments such as these that make me so very glad Turner Classic Movies is around to give us an “Aline MacMahon day,” such as they did last week. There are so many classic gems to be discovered from lesser known artists such as Miss MacMahon. Once more, glad you found her and thanks for sharing the experience here.

Cliff