Little Lord Fauntleroy is yet another period piece based on a literary classic from David O. Selznick. In this case a classic of children’s literature. This was the first film Selznick produced for his Selznick International Pictures after leaving MGM. The casting is near perfect; The adaptation as a whole comes close too!

I read a copy of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s story just prior to my latest view of Little Lord Fauntleroy and if you didn’t know any better you would think that the Burnett novel was adapted from the film instead of the other way around!

Novelist Hugh Walpole actually wrote this screenplay and he must have really taken a liking to Burnett’s original source when doing so. The differences in action are minimal and mostly involve Mr. Hobbs and Dick the bootblack. The dialogue matches–exactly–almost throughout. It’s a credit to the actors that these lines, cribbed directly from the novel, are delivered mostly to perfection. Once more it’s that fine casting.

The Characters from Book to Screen

Burnett wrote:

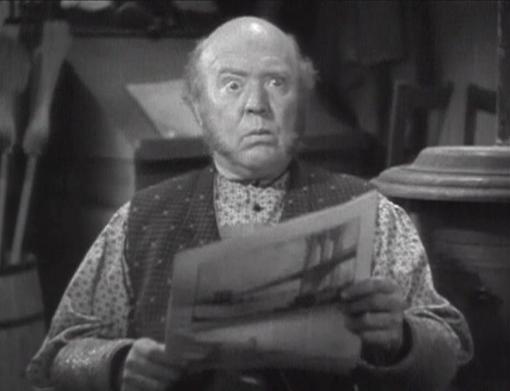

“The fact was, Mr. Hobbs was not a clever man, nor even a bright one; he was indeed rather a slow and heavy person, and he had never made many acquaintances. He was not mentally energetic enough to know how to amuse himself, and in truth he never did anything of an entertaining nature but read the newspapers and add up his accounts. It was not very easy for him to add up his acounts, and sometimes it took him a long time to bring them out right …” (187)

Describing Guy Kibbee to a tee as Mr. Hobbs:

Burnett wrote:

“A tall, thin old gentleman with a sharp face was sitting in an armchair … The tall old gentleman rose from his chair and looked at Cedric with his sharp eyes. He rubbed his thin chin with his bony hand as he looked. He seemed not at all displeased” (13-14).

Presents Henry Stephenson as Mr. Havisham:

Burnett wrote:

“She looked in the simple black dress, fitting closely to her slender figure, more like a young girl than the mother of a boy of seven. She had a pretty, sorrowful young face, and a very tender, innocent look in her large brown eyes–the sorrowful look that had never quite left her face since her husband had died” (23-24).

We have Dolores Costello as Dearest:

Burnett wrote:

“And then the Earl looked up. What Cedric saw was a large old man with shaggy white hair and eyebrows, and a nose like an eagle’s beak between his deep fierce eyes” (78).

The Earl of Dorincourt could be no one other than C. Aubrey Smith:

Long before we actually meet the Earl he is brought to life early in the novel via Mr. Havisham:

“He was thinking of the old Earl of Dorincourt, sitting in his great, splendid gloomy library at the caste, gouty and lonely, surrounded by grandeur and luxury, but not really loved by anyone, because in all his long life he had never loved anyone but himself; he had been selfish and self-indulgent, and arrogant and passionate; he had cared so much for the Earl of Dorincourt and his pleasures that there had been no time for him to think of other people; all his wealth and power, all the benefits from his noble name and high rank, had seemed to him to be things only to be used and amuse and give pleasure to the Earl of Dorincourt; and now that he was an old man, all this excitement and self-indulgence had only brought him ill-health and irritability and a dislike of the world, which certainly disliked him. In spite of all his splendour, there was never a more unpopular old nobleman than the Earl of Dorincourt, and there could scarcely have been a more lonely one” (45-46).

And while Burnett’s description of Ceddie through the Earl’s eyes is not as exactly matched on film visually:

“What the Earl saw was a graceful childish figure in a black velvet suit, with a lace collar, and with love-locks waving about the handsome, manly little face, whose eyes met his with a look of innocent good-fellowship” (78).

It turns out to be a blessing that Freddie Bartholomew was not as decorative as the child Burnett describes. Burnett’s vivid description of Ceddie’s appearance in the late nineteenth century, so vivid that it revolutionized boy’s fashion for a time, aged very poorly. Even toned down Bartholomew’s Ceddie is strange enough in manner to have a hard time with boys his age in the 1936 movie. I don’t think the velvet and golden curls would have flown well with a youthful audience in the 1930’s, so thank goodness we don’t have to see them today!

Thankfully all of Ceddie’s personality traits remain in the film and are portrayed skillfully by young Bartholomew.

Burnett’s literary Mr. Havisham perfectly describes the boy to his employer after the Earl presumes his grandson will embody all of the worst American traits he can imagine:

“‘It is not exactly impudence in his case,’ said Mr. Havisham. ‘I can scarcely describe what the difference is. He has lived more with older people than with children, and the difference seems to be a mixture of maturity and childishness'” (68).

Young Fauntleroy’s charms begin to work on the old Earl almost from their first meeting:

“He was not bold; he was only innocently friendly, and he was not conscious that there should be any reason why he should be awkward or afraid. The Earl could not help seeing that the little boy took him for a friend and treated him as one, without having any doubt of him at all. It was quite plain as the little fellow sat there in his tall chair and talked in his friendly way that it had never occurred to him that this large, fierce-looking old man could be anything but kind to him, and rather pleased to see him there. And it was plain, too, that in his childish way he wished to please and interest his grandfather. Cross and hard-hearted and worldly as the old Earl was, he could not help feeling a secret and novel pleasure in this very confidence. After all, it was not disagreeable to meet someone who did not distrust or shrink from him,, or seem to detect the ugly part of his nature …” (85-86).

The Basic Story of Little Lord Fauntleroy

Little Cedric Errol (Bartholomew) grows up in Brooklyn in the 1880’s under the care of his mother whom he simply calls Dearest (Costello). This is what his late father, the third son of the Earl of Dorincourt, had called Ceddie’s mother and so Ceddie does the same. Due to the casting Ceddie also speaks with his father’s accent which actually turns out to be a nice touch in helping to stress his attachment to his parents. Ceddie and Dearest are the closest of friends.

After Dearest gives Ceddie a bicycle he goes off on his daily adventures and we meet his closest friends, Dick the boot-black (Rooney) and shopkeeper Mr. Hobbs (Kibbee). It’s while passing the time with Mr. Hobbs that Dearest’s servant, Mary (Una O’Connor), comes to retrieve him and brings Ceddie home to meet Mr. Havisham (Stephenson).

Mr. Havisham has come from England under the employ of the Earl of Dorincourt (Smith) with orders to retrieve Ceddie to his castle across the sea and set him up as the Earl’s successor. “So this is little Lord Fauntleroy,” says Mr. Havisham upon meeting Ceddie.

The situation is explained and Ceddie soon thinks his grandfather, the Earl, must be a fine man because he’s instructed Mr. Havisham to let Ceddie have anything he wants. It is Ceddie whose every whim is to help others. But since he’s able to provide this aid by way of the Earl’s great fortune the young boy transfers all of his own goodness onto his grandfather, whom we know is far from an admirable sort long before we meet him.

What Ceddie is not told, but is explained to Dearest and us, is that his supposedly kind grandfather refuses to have anything to do with Dearest. Thinking Americans vulgar in general and having distanced himself from his son while he was still alive for having married one, the Earl allows Dearest to accompany her Ceddie to England but she has to live in a separate house and have no contact whatsoever with the Earl.

The revelation to Ceddie of his separation from Dearest is actually better accomplished in the movie than in the novel as Ceddie is not told of their parting until after having arrived in England in the film. He’s better prepared in the novel. Ceddie is heartbroken in each case but follows Dearest’s instructions not to question his grandfather about the situation the old man has imposed.

While Ceddie spends one last evening with Dearest, Mr. Havisham returns to the Earl’s castle to inform his employer about his impressions of the boy. The Earl has low expectations and finds fault with everything Mr. Havisham tells him. But when the Earl meets Ceddie the next morning he quickly finds himself disarmed by the boy’s innocent nature and a great companionship begins to form as the Earl presumes to teach Ceddie about his responsibilities while Ceddie instead shows the Earl how those responsibilities are best used.

Just as the formerly cranky old Earl becomes most attached to Ceddie the boy’s role as his heir comes under threat from an outsider. The situation appears completely helpless until the American papers reveal a rather big coincidence to Dick the bootblack who undertakes to save Ceddie’s position as Lord Fauntleroy with the assistance of Mr. Hobbs.

Commentary and (Mostly) Praise

As a literal translation from the page to the screen Little Lord Fauntleroy is near perfection. As illustrated above the casting is practically dead on.

The weakest link of the main characters is Dolores Costello as Dearest, though her part may have been the most difficult to play. Her Dearest, an adult remember, is even more virtuous than little Ceddie. It’s her nature which molds his nature and thus some of the lines she has to deliver, again direct from Burnett’s late 19th Century novel, are a bit too innocent for any adult to ever speak.

Mickey Rooney makes the mistake of playing Dick the bootblack with a very poor Brooklyn accent. He says “oils” when speaking of Ceddie’s future position and likewise “diamonds and poils” when those particular riches are brought up. Rooney mentions being on “foreign serl,” and dishing out what one “desoives.”

Mickey Rooney can seemingly do it all on film but accents do seem to be his downfall. Rooney made himself hard to stand in another Freddie Bartholomew movie when he played with an Irish accent in Lord Jeff (1938) a few years after this one. The All-American boy Rooney is at his best when he sounds like one. And so he’s pretty hard to stand in Little Lord Fauntleroy.

While we hear plenty about the Earl of Dorincourt we don’t actually meet the C. Aubrey Smith character until over 40 minutes into the movie. That said, Little Lord Fauntleroy is overwhelmed by his presence and the pairing of Smith and Freddie Bartholomew is the most memorable element of the movie.

It’s really as though the Earl’s misery is a contagious disease that his grandson acts as medicine for. The Earl is at first guarded and when Ceddie manages to get him to do good he only does so out of his own pleasure of the boy’s pleasure–not to actually help anybody.

But as little Ceddie works upon his system the Earl finds himself leaving his gout pillow behind to play marbles on the floor and walk freely about with his grandson. In Burnett’s book he even took up riding his horse again after many years! His general disposition improves a little at a time. By the end of the film the enjoyably uncomfortable meeting between the Earl and Mr. Hobbs finds C. Aubrey Smith’s Earl not too disagreeable fellow at all.

Little Lord Fauntleroy was David O. Selznick’s first film produced at his Selznick International Pictures after leaving MGM. It was faithfully adapted by Hugh Walpole from the Frances Hodgson Burnett novel of 1885 (1886 in book form) and directed by John Cromwell. The film was released through United Artists in March 1936.

Also appearing in Little Lord Fauntleroy beyond those already mentioned above are Jessie Ralph as Ceddie’s pal, the applewoman, and Constance Collier as the Earl’s sister, Lady Lorridaile. E.E. Clive plays her husband. Virginia Field appears in one scene as beautiful Miss Herbert whom young Ceddie greatly admires to everybody’s innocent amusement. It might spoil things to tell too much about Helen Flint and Jackie Searl, but I will say that they were appropriately obnoxious in their parts.

Frank S. Nugent in his April 3, 1936 review in The New York Times makes clear that Fauntleroy does not approach Selznick’s two previous literary adaptations, David Copperfield and Anna Karenina, both 1935 releases that also featured Freddie Bartholomew, but that in the case of Fauntleroy “Selznick has transferred it to the screen with equal consideration and understanding.”

Nugent gives his blessing to the shedding of the velvet and curls as well and adds that “There is a benign aura about the photoplay, a mellow haze of things long past which should lull even the most adamant anti-Fauntlerite into a state of restful receptivity.” In other words, don’t be put off by any preconceived notions you may bring to Little Lord Fauntleroy because “the picture has a way with it and, unless we are very much in error, you will be pleased.”

I’ll second that and heartily recommend Little Lord Fauntleroy to men, women and children alike.

Have you ever had a hard time with a novel after seeing the movie first? The characters on the page just don’t fit the mold that the movie has already cast in your head? That is not the case with Little Lord Fauntleroy. The reading experience is enhanced thanks to Selznick International and especially Freddie Bartholomew and C. Aubrey Smith.

Sources:

- Burnett, Frances Hodgson. Little Lord Fauntleroy. 13th ed. New York: Penguin Putnam Inc., 1994.

- Nugent, Frank S. “Little Lord Fauntleroy, a Pleasant Film Version of the Familiar Novel, at the Music Hall.” New York Times 3 Apr 1936.

[phpbay]freddie bartholomew|aubrey smith, 12, “”, “”, “”, “”, 29[/phpbay]

Leave a Reply