J.M. Josefsberg can’t understand why the movie “Employees’ Entrance” wasn’t a success. He figured that most people were going “just to see what an employees’ entrance looked like!” – From Walter Winchell’s “On Broadway” column, February 3, 1933.

Released by First National and distributed by parent company Warner Brothers, Employees’ Entrance follows Warners’ ripped from the headlines program, with much of its drama derived from the plight of the worker during the darkest days of the Great Depression. In that light Warren William’s Kurt Anderson is the villain of the piece, a ruthless tyrant who sends outside help into bankruptcy and preys on his own employees’ desperation to the point where they must either shut up and take it, oppose and wind up another of the unemployed, or even in one case leap to their death from a ninth story window.

What makes Employees’ Entrance all the more interesting is that William’s Kurt Anderson is not the villain of the piece.

Despite all of Anderson’s bluster the working class fare much better at his hand than do those whom he especially despises: the fat cat executives above him on the inside and especially the bankers on the board, who in Anderson’s own words are not producers.

Anderson remains the hero despite his misogyny, despite his complete lack of empathy, and despite his interest in only the bottom line because Anderson is a self-made man who rose through the ranks and achieved his success solely through merit. If you took all the cast of Employees’ Entrance and divided them into working-class and the elite, not only would Anderson stand on the side of the worker, he’d be their leader!

Despise him all you want, in a pinch Anderson is the man you’re looking to follow.

Employees’ Entrance opens with a quick history of the Franklin-Monroe department store which we’re told was established in 1878. Anderson is also introduced in this montage of complaints coming from people aligned with the business from the inside and out, employees and contractors. Superimposed over those complaints is the tale of the Franklin-Monroe’s rise, beginning in 1920 when Anderson came on board, from $10 million in annual sales to $25 million in 1925 to an impressive $100 million in 1929. As the people complain the store’s namesake and top executive, Franklin Monroe (Hale Hamilton), he descended directly from both Benjamin Franklin and James Monroe with all merit ending there, lets them down with apologies and explanation that the decisions are all up to Mr. Anderson.

We meet the executives at a Franklin-Monroe board meeting where Monroe himself is more concerned about his chairmanship of the Mayor’s Welcoming Committee and his cousin, a lackey named Ross (Albert Gran), seconds his every word. The bankers are satisfied with earnings and everyone knows that the continued success of the store is due to one man. Anderson sits sneering at them all before demanding his salary be doubled and he be given total control. “My code is smash … or be smashed,” he declares while tossing insults at Monroe’s welcoming committee duties. While Monroe demands the impudent Anderson be ousted, he has no time to fight for his position as he runs off to welcome the Trans-Atlantic fliers. With Monroe out the door the satisfied bankers vote to retain Anderson on his own terms.

And this is all before the Crash!

After witnessing Anderson dominate his meeting with the executives we next see him in action defending the Franklin-Monroe from the incompetence of outsiders. An independent contractor, Mr. Garfinkel (Frank Reicher), was to supply swagger coats to the Franklin-Monroe for a big sale they had advertised, but he’s three days late with the order and can only supply a fraction of the coats that he’d agreed to.

Despite Garfinkel’s pleas that he has $30,000 invested in this deal, a deal he’s already taking a loss on just to earn future business from the big Department store, Anderson heaps his wrath upon him. He tells his secretary to cancel the order and sue Garfinkel for the advertising fees. Garfinkel pleads, “It’s my life,” which grabs Anderson’s attention. His head snaps up and he tells Garfinkel, “Merchandise is the life of this store. When you promise to deliver on a certain day and don’t do it you threaten our life!” Garfinkel persists, “It only happened once, it can’t happen again,” to which Anderson shouts “It can’t happen once! Now get out of here.”

Anderson is just is ruthless with those who work inside the Franklin-Monroe but threaten it’s well-being, especially those from the higher ranks. His second in command is an older man named Higgins (Charles Sellon) who has been with the company since 1906, but makes the mistake of conservatively preaching retrenchment once the Depression reaches in to knock annual sales back down to $45 million. Disgusted with him, Anderson turns his attention to the youngest man in the room, Wallace Ford’s Martin, whose suggestion about selling men’s drawers to women intrigues Anderson but is too radical for Higgins (“You think a thing can’t be done because it hasn’t been done!”).

Asked what he thinks Higgins says, “Fantastic. Not at all in line with the policy of the store. And I’ve been 30 years in the business.” Barely a second passes before Anderson explodes: “Higgins, get out! You’re through.” Higgins pleads, “Not publicly like this,” to which Anderson replies “Publicly or privately you’re through. You’re too old … You’re dead wood.” When Higgins repeats that he’s been 30 years with the company, Anderson spits back that he’s already been paid for his previous work and orders, “Now get out.”

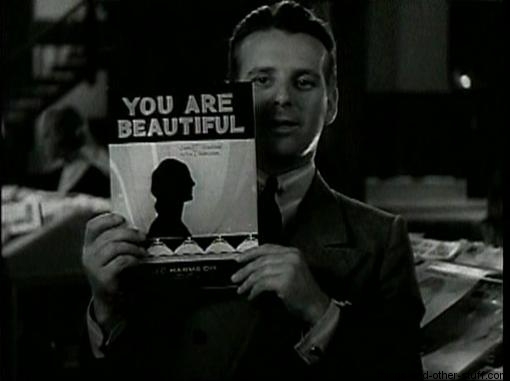

Employees’ Entrance shows us the life of the Department Store through brief glimpses of a few departments and a regular elevator ride where all of the varied departments are rattled off floor by floor by the elevator operator. While we’re never shown the men’s drawers display an interesting peek at the times is offered when Martin shows his initial interest to model Madeleine (Loretta Young) by mooning over her and winning her attention by holding up sheet music with suggestive titles in her view from what’s seemingly endless display.

According to David E. Kyvig in Daily Life in the United States, 1920-1940, “Retail sales work had begun to change in the late nineteenth century as large department stores set out to dominate the urban commercial scene. Department store relied on volume sales stirred by lower prices as well as greater selection of goods and services to compete successfully with specialty stores … Determined to cut costs, department and chain stores relied far more on the eye-catching goods than on the sales staff’s knowledge of products and customer needs. Sales work came to require few substantial skills; instead it became primarily a matter of gracious treatment and gentle encouragement of customers who examined products for themselves …” (39), which is consistent with Martin’s brainstorming of the men’s drawers idea as well as the general store activity that we’re shown.

One incident that further colors the Kyvig quote as well as giving another look into the seemingly perverted notions of Kurt Anderson occurs when the store dick, Sweeney (Allen Jenkins), brings Mrs. Hickox (Marjorie Gateson) to Anderson’s office. Mrs. Hickox is outraged because the detective has accused her of stealing her own purse. While Anderson turns on the charm with her you can see him lose any ground he had to stand on when Mrs. Hickox informs him that her husband is editor of one of the city’s bigger newspapers. Anderson asks if there might not be some item in the store she would like to have as a token of apology and to keep the incident from the papers. Mrs. Hickox winds up with a Concert Grand Piano which poor Sweeney is going to have to pay off $10 per week for the rest of his life–and beyond. Telling about Anderson in this incident is that he doesn’t fire the detective.

The lifeblood of the Franklin-Monroe is its workers and Anderson realizes that more than anyone else. He respects a job well done and that’s what eventually draws him closer to Martin.

After Martin had come to his attention with the men’s shorts brainstorm he earned further respect when Anderson spotted him letting down an advertising artist–brutally. “That’s the way to do it, my boy,” Anderson tells him before offering up Higgins’ old job as his second in command. He wants to make sure Martin isn’t married as “this is no job for a married man,” and Anderson would require 24 hour access to him. Martin, very hesitantly, asks “Don’t you like women?” Anderson blusters “Sure I like them. In their place. But there’s no time for wives in this job. Love ’em and leave ’em. Get me?”

Martin agrees to advance his career but away from Anderson’s view he’s become more involved with Madeleine and he soon overcomes Anderson’s voice in the back of mind and marries her. Madeleine despises Anderson and fears Martin may become like him if he follows too closely in his footsteps. She has good reason to loathe him; Madeleine was one of those whom Anderson loved and left, and while he did charm her in their first meeting she had no choice but to give in to him if she wished to land employment at the Franklin-Monroe.

“Give me a job–at ANY price!” were the text above the image of Loretta Young, just 20 years old, pushing a leering Warren William away from her. The advertisement for Employees’ Entrance continued with the open ended tag “The cry of a million heart sick girls waiting in line at Employees’ Entrance,” leading the customer to wonder whether they meant in the film or at the film. The last line of marketing before listing the rest of the cast stated the film “Probes the desperate moral problem of America’s out-of-work girls.”

Young’s Madeleine caved to Anderson’s advances in their first scene with one another. Madeleine was so broke that she was discovered by Anderson camping out in the home section of the department store, both because it beat her current living situation and also to give her an advantage in the Franklin Monroe’s employment line the next morning. Upon discovering that the man she’s flirting with is the notorious Kurt Anderson she allows him to buy her dinner and then finds herself in his apartment. Anderson undresses her with his eyes while she laments not being in a position to pay him back for his kindness, but when she goes to leave he blocks her way with a kiss and shows her there are other ways to pay back a debt. She begins work at the Franklin Monroe the following morning.

As Employees’ Entrance progresses Madeleine and Martin fall in love and are married in a somewhat awkward scene, one of only a few outside of the Franklin-Monroe. Meanwhile Anderson lures Martin into a closer relationship by his own example and the carrot of success. Madeleine and Anderson manage no further day to day contact until the relationship of all three main characters is further complicated at the Franklin-Monroe Annual Ball. The young couple have an argument and split up at the party, each drinking too much after going their separate ways. While Martin contents himself by singing barbershop numbers with fellow Franklin-Monroe staff until he passes out amongst the debris, Madeleine has the misfortune of a second meeting with Anderson, who’s otherwise bored with the whole affair until spotting his past conquest.

They have drinks but while Madeleine grows more inebriated by the moment, the calculating Anderson always seems to have his head about him. Finally in her confused state Madeleine accepts Anderson’s invitation to take the key to the room he’d reserved and lie down for awhile. Anderson promises he’ll wait for her at the party, but before we see Madeleine flop across his bed he’s already striding down the hallway tailing her all the way to the room where he lets himself in. She’s strewn across the bed passed out. He closes the door and stays the night. As Mick LaSalle writes in Dangerous Men, “It’s tantamount to rape. She’s practically in a coma” (157). Even taking the extremes that Anderson drives Higgins to under consideration, his second night with Madeleine is definitely the characters’ most damning moment.

The drama is escalated as Madeleine regrets this second mistake with Anderson, while Anderson, still ignorant of Martin’s marital status embraces him as a son by way of stern words and dictate. Sales at the Franklin-Monroe continue to plummet and Monroe himself is away on a yacht leaving voting interest of the company in the hands of the bankers who have soured on Anderson. Anderson is forced to form an alliance with Monroe’s dimwitted cousin Ross who he’d previously kept at bay by busying him with the bought and paid for affections of Polly Dale, played by Alice White in her return to the screen after a two-year absence.

As Anderson’s position with the Franklin-Monroe becomes more and more threatened by the ticking of the clock against contacting Monroe, he also discovers that Martin is not only married, but married to Madeleine, whose conduct with him further confirms his low opinion of women in general. The finale of Employees Entrance swirls around poison, a gun shot and the race to put down the bankers’ vote.

Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times wrote that Employees’ Entrance “is a decidedly fictional type of story, but one which despite certain melodramatic notions succeeds in holding one’s attention.” He boils Anderson down to the essentials writing that he “is a tireless worker who expects all in his store to be on their toes. A slow brain exasperates him, and obstinacy usually ends with a dismissal. He has no use for sentiment in business, but he occasionally indulges in an affair with an attractive girl.” An unsigned review in the February 6 edition of the Wisconsin State Journal uses a bit more panache to similarly state of Warren William’s Anderson, “As a cold-hearted, slave driving executive of a big department store he banishes sentiment from business and manages to make himself respected and despised at the same time.” Later that week another anonymous writer, this time for the Chilicothe Constitution Tribune, also puts the focus on Anderson writing “Primarily the story is a great character study, graphically illustrating what happens to those who come in contact with the cold-blooded, ruthless, domineering Kurt Anderson, either in a business or social way.”

Warren William is fantastic as Anderson. Nobody could spit out business venom as he could and manage to remain human while doing so. As the period reviews confirm, he is the movie. Loretta Young calls upon youth and beauty more than talent at this point, but youth and beauty work quite well for a 20-year-old Loretta Young! Her best scenes are with William, especially when she pleads with him to spare Martin for her which it should be noted that in a very twisted way, Anderson does. Wallace Ford is given a lot more to do in Employees’ Entrance than he was in Skyscraper Souls and he does it well. While his scenes with Young are nothing special there’s a confused intensity in most of his scenes with Anderson due to his harboring dreams of reaching Anderson’s status with fear of actually becoming like the man.

I’ll wind down by recommending that you see this picture at any cost if you’re a fan of pre-Code era films. While Warren William is not often remembered today it is the type of character he played in Employees’ Entrance and other films of the pre-Code period that should be his legacy. On a personal note, Employees’ Entrance more than any of his other films was the one which led to my creation of a Warren-William.com tribute site in 2007. I’d been saving this review up for awhile because of my special fondness for Employees’ Entrance, and so I’m posting a second piece on Warren-William.com to better explain why this character sold me on Warren William as well as further explanation of the complicated character of Kurt Anderson.

Employees’ Entrance is available as a manufactured-on-demand DVD-R from Warner Archive in their Forbidden Hollywood Collection: Volume 7. Released in April 2013, this four-movie set also includes Edward G. Robinson in The Hatchet Man, Bette Davis in Ex-Lady, and more Warren William in the equally fantastic Skyscraper Souls. No better introduction to Warren William can be had than through purchase of this set, containing his twin pre-Code gems.

[…] Aliperti has done an extensive job documenting this, calling it one of his favorite films. His Immortal Ephemera site has more of a general review of the piece, where he explains his fascination with Kurt […]