The Roaring Twenties is one of James Cagney’s four most iconic gangster portrayals; the one where “he used to be a big shot” by the end of the movie. Cagney’s big four are linked in our memories by their huge finishes, memorable exclamation points for each of Cagney’s excitable mugs. They stain a montage of death and murder in our minds with classic scenes propped even higher through classic lines uttered either by Cagney or to him: “I ain’t so tough,” he realizes just before collapsing in the rain in The Public Enemy (1931) on his way to even more violent exit; Father Jerry (Pat O’Brien) asks him for one last favor in Angels With Dirty Faces (1938) leading into the most famous death house stroll in movie history; the irony isn’t lost on Panama Smith (Gladys George) when she states Eddie (Cagney) used to be a big shot at the end of The Roaring Twenties; and, of course, “Made it, Ma! Top of the world!” in Cagney’s most violent and sudden exit in White Heat (1949) ten years later. If four people sat down to talk about Cagney’s gangster roles and each of them named a different favorite, nobody would be wrong.

The Roaring Twenties was awarded, at best, grudging praise from Frank S. Nugent, who reviewed it in 1939 for the New York Times. We’re looking back at this after more than seventy-five years, but for Nugent and his contemporaries The Roaring Twenties marked the revival of a genre done to death just a few years before. “The dirty decade has served too many quickie quatrains to rate an epic handling now,” Nugent wrote, unable to see an everlasting classic that had actually tied a bow on all those Roaring Twenties flicks preceding it.

Following the gritty offerings of the late Silent and pre-Code eras, it might be said that The Roaring Twenties topped it with a pretty bow: It was neater, cleaner, a bit more polite, a masterful product of the studio era, yet it was also elevated by the animal magnetism of performers like Cagney and Humphrey Bogart, even Gladys George, who each grounded their characters through an edgy and innate earthiness that created personalities that outsized the movie. The foxholes and speakeasies, the cab company, and even the jail are squeaky-clean movie settings in appearance, but the performers, especially those three key participants are happy to show their dirt and bare their souls.

Mark Hellinger is best remembered today as a producer, most notably of The Killers (1946). Before Hollywood, he was another one of those great real-life characters out of New York in the Roaring Twenties, where he made his name as a Broadway columnist. The Roaring Twenties was adapted by several writers from Hellinger’s original story The World Moves On, a fifty-page treatment he had submitted to Jack Warner. His familiar characters have their basis in fact, and we’ve seen them on screen before in various guises.

Cagney’s Eddie Bartlett is based upon Larry Fay, who more or less invented the glamorous twenties speakeasy as it has been handed down to us from history—and the movies. Fay was a cab driver who fell into bootlegging after driving a fare to Canada and returning to New York with several bottles of Canadian whiskey hidden in his cab. He was pals with Owney Madden, who he used for protection, but it was press agent, radio figure, and revue producer Nils Thor “Granny” Granlund who introduced Fay to Texas Guinan. Already hostess at a classy New York speakeasy, Guinan was lured into a partnership with Fay when he offered a fifty-fifty split and soon, with the financial backing of Madden and Arnold Rothstein, Fay opened up his club, The El Fey, where Guinan achieved notoriety welcoming the suckers in for an evening’s fun and entertainment. Gladys George plays the Guinan character, Panama Smith, in The Roaring Twenties.

Note: For the best of both worlds and a true flavor of the times, I’ve clipped a lengthy profile of Larry Fay authored by Mark Hellinger from a 1927 newspaper.

There’s a worthy pre-Code predecessor to The Roaring Twenties in Broadway Thru a Keyhole (1933), a Walter Winchell story that was an early release from Darryl F. Zanuck’s new 20th Century company. This was the movie that earned Winchell a well-publicized punch in the nose from Al Jolson. You see, before marrying Jolson, young Ruby Keeler was hired by Granlund as a dancer for Fay and Guinan at El Fey’s. Ruby was involved with a mobster—usually reported as Johnny “Irish Costello (see books by Billy Grady, Neal Gabler), though sometimes named as Larry Fay (Leonard Maltin and AFI.com go this route, so does Jolson himself in that clipping I linked to earlier in this paragraph). Anyway, regardless of the specific thug in question, Jolson wasn’t happy with Winchell bringing such a thinly veiled version of his and Ruby’s lives to the screen.

In an additional interesting aside, Paul Kelly—the actor who plays Nick Brown, the gangster Bogie throws over for Cagney, in The Roaring Twenties—plays the Fay/Costello character Frank Rocci in Broadway Thru a Keyhole. More notably, Texas Guinan herself plays the Texas Guinan character, Tex Kaley, in the earlier movie. The all-too-sweet Keeleresque ingenue is handled by Constance Cummings in Broadway Thru a Keyhole, a part that has a lot in common with Priscilla Lane’s Jean Sherman a few years later in The Roaring Twenties.

In an additional interesting aside, Paul Kelly—the actor who plays Nick Brown, the gangster Bogie throws over for Cagney, in The Roaring Twenties—plays the Fay/Costello character Frank Rocci in Broadway Thru a Keyhole. More notably, Texas Guinan herself plays the Texas Guinan character, Tex Kaley, in the earlier movie. The all-too-sweet Keeleresque ingenue is handled by Constance Cummings in Broadway Thru a Keyhole, a part that has a lot in common with Priscilla Lane’s Jean Sherman a few years later in The Roaring Twenties.

The Roaring Twenties offers a superior version of the Broadway Thru a Keyhole yarn, additionally framed throughout by the era itself, from the World War I foxholes through the entire age of Prohibition that followed. The three main male characters are introduced during the war, which allows for a stark revelation and contrast of each of their characters: Bogart is George, already graduated from cynic to killer. “You know I like this,” he says of his weapon after armistice has been declared. “I think I’ll take it with me.” Jeffrey Lynn is Lloyd, peace-loving prospective lawyer who has had enough of war and killing. Bogart can smell class and education all over Lloyd and takes every opportunity to kick him while he’s down, smirking and sneering at the fresh-faced youngster’s aversion to violence. Cagney is Eddie Bartlett, our everyman who can get along with both extremes offered by George and Lloyd. He just wants to go home and go back to being a mechanic. “All I know is I don’t want any more trouble,” Eddie tells the others. “I’ve had some.”

The men come home and get on with their individual lives. We follow Eddie, who returns to roomie Danny (Frank McHugh) and quickly discovers, as the title of Hellinger’s original story had warned, the world has moved on without him. Through Cagney’s character we see the troubles that the veterans faced in coming home: promises broken by too much time away. He’s been replaced at work and any sense of gratitude for services rendered, over here or over there, has been ground to dust. Eddie is unsettled until Danny offers him partial use of his cab. The two kick back and take a trip to Mineola to visit the beauty (Priscilla Lane) who had written Eddie letters throughout the war. Eddie is disappointed to discover his pen pal is just a high school girl all glammed up in the snapshot she sent, so the boys depart somewhat rudely with Eddie promising to call her, “in about two or three years, when you’re a big girl.”

The movie boasts a narrator (John Deering), whose interruptions accomplish their goal in lending The Roaring Twenties a March of Time newsreel-feel. He pipes in at this point to usher in the twenties and Prohibition. It doesn’t take long for Eddie to run afoul of the new law when a fare asks him to deliver a package to the Henderson Club. Too green to see what he’s been asked to do, Eddie’s delivery and subsequent arrest manage to introduce him to club hostess Panama Smith (George), while also bringing back war buddy Lloyd to defend him in court. Lloyd gets Panama off, but Eddie is found guilty and faced with a hundred dollar fine or sixty days in jail. “You give any credit around this joint?” Eddie asks the bailiff. “Sure we do. You’ve got sixty days to pay.”

Panama returns to pay Eddie’s fine and rescue him from jail, and the two settle down to talk turkey in a speakeasy found in the back of the “Paints and Varnishes” shop. A nice touch is the cop who rouses one of the customers for parking, then signals the bartender for what he’s really come in for:

Eddie accepts Panama’s invitation into the liquor business and the underworld. He starts small, peddling booze on the street in a montage of scenes that ring a lot of bells when thinking back to Cagney’s earlier screen wiseguys. After his suppliers raise the cost of goods, Eddie and loyal pal Danny start making their own bathtub gin, which we even get to see pass muster with the drinking public: “This is the real stuff, you can’t fool me,” says a happy customer after a big swig of Gorman’s, Eddie’s label.

Eddie follows the Larry Fay playbook and puts all of his profits into cabs, buying up a fleet for his next rainy day. He begins hiring ex-cons (“No geraniums” wanted) for his bootlegging business, and the small-time outfit grows into a criminal empire that rivals legitimate corporations in size. One day Eddie heads out himself to demand cash payment from a deadbeat Broadway producer (George Meeker) and is delighted to discover his old pen pal, Jean Sherman (Lane), all grown up and leading the chorus line. Eddie forces an audition for her at Henderson’s night club, where Panama is hostess.

“She seems like a nice kid,” Henderson (Ed Keane) says. “I hope she can outtalk him.”

“I hope she can outrun him,” Panama replies, after watching how Eddie mooned over Jean.

Jean is hired, on Eddie’s private terms with Henderson, and romance seems ready to bloom until Eddie introduces her to his lawyer pal, Lloyd. There’s an immediate flicker between Jean and Lloyd, two kids much more even in temperament and experience than Eddie is to Jean. Eddie shows off his operation to Jean, bragging about the markup the suckers pay for his faux champagne. Jean thinks he’s cheating, but Eddie assures her, only if you get caught. It’s the lure of the short cut and the easy buck that keeps Eddie from ever truly winning Jean. The idea that you should “take what you can get while you can get it.” Much later Eddie buys Jean a new radio set that she wonders over. “Ought to be good,” Eddie says: “I paid a lot of money for it.” Lloyd’s tone is drained of emotion as he replies, “Yes, that makes it good. That makes anything good.” Lloyd has figured out Eddie by this point, and Jean is beginning to see him for what he really is too.

George’s (Bogart) return, in a nice episode dramatizing the twelve-mile limit, brings an even darker influence to Eddie’s life, and though Eddie remains his own man, and always the superior of the two partners, George associates him with new forms of bad behavior, namely murder. George begins the body count, but Eddie winds up escalating it through a later call to vengeance after war breaks out with Nick Brown (Kelly). It becomes too much for the younger set, though Eddie notably holds on to some humanity when he stops George from plugging Lloyd after Lloyd severs ties with the gang. A little later Eddie’s temper gets the best of him and he slugs Lloyd, but he relents when Lloyd picks himself off the ground and asks, “What are you trying to prove?”

“Nothing, kid, nothing. Sorry. Sorry,” Eddie says.

He’s still got a lot of baggage to pick up and drag him down, notably the Stock Market Crash, but this moment of clarity shows that Eddie already really knows what Panama has to convince him of later, after he’s tumbled as low as he can go: “Eddie, you’re kidding yourself, the race is over,” she tells him. “We’ve both finished out of the money.” The world has moved on, yet again. Eddie takes the lesson to heart and tries to explain it to George with hopes of saving Lloyd—and thus Jean—from George’s wrath, but George is still sitting pretty. This launches the violent end to The Roaring Twenties, which finishes with Panama’s declaration that Eddie “used to be a big shot.”

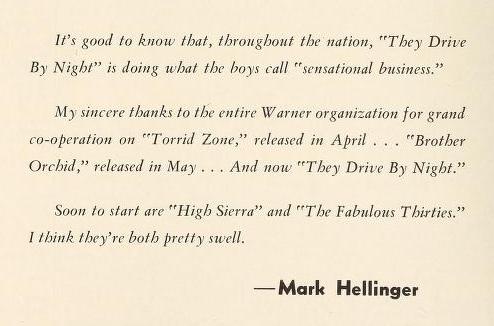

The Roaring Twenties was such a hit that in July 1940 the trade papers mentioned that Cagney, Bogart, and director Raoul Walsh would reunite on Mark Hellinger’s The Fabulous Thirties. By September it was two other members of The Roaring Twenties cast, Priscilla Lane and Jeffrey Lynn, who were touted as the stars of the upcoming production alongside John Garfield, with Lloyd Bacon now set as director. Lane, Lynn, and Garfield had appeared together in Four Wives (1939), but The Fabulous Thirties wound up an unproduced curiosity. A copy of the original 1939 script for The Fabulous Thirties was included in this lot of Mark Hellinger scripts auctioned by Heritage in 2009.

Raoul Walsh also directed Bogart in They Drive By Night (1940) and the actor’s major breakthrough in High Sierra (1941), among other films, though I mention those two titles because Mark Hellinger also served as associate producer on both of them. Walsh next worked with Cagney in The Strawberry Blonde (1941), and then ten years after The Roaring Twenties in Cagney’s legendary return to gangster roles, White Heat (1949), which puts a nice bow on this article in referring back to its open.

The Roaring Twenties came to DVD in (fittingly) the first Warners Gangster box set. It’s also available as a single DVD and for streaming at Amazon.com.

References

- Miller, Donald L. Supreme City: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015 (2014).

- “Name Writers Signed by Republic in Expansion.” Motion Picture Daily, July 24, 1940, 6.

- Nugent, Frank S. “The Screen: Reviews and News.” New York Times, November 11, 1939. http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9500E5DB143EE432A25752C1A9679D946894D6CF.

- Profumo, Tony. “The Roaring Twenties,” Films of the Golden Age, accessed June 19, 2016, http://www.filmsofthegoldenage.com/articles/2003/12/17/current_issue/twenties.txt.

- “10 Features Start In Coast Studios,” Film Daily, September 17, 1940, 7.

I didn’t know I wanted to get up and read such an interesting article first thing in the morning.

When I was a kid waiting for it to appear on the late show, “The Roaring Twenties” was soaring and epic. Now it is a dear and comfortable old friend. You have me wondering about the next time.

Thanks @CaftanWoman, you never know when I may have one coming—heck, I barely know myself. I hope the background makes for a little extra enjoyment the next time you watch.

Once again (as ever and always), an intelligent, masterful review! I always go for scholarship over opinion and you never fail me. Thank you.

Thanks for taking time to comment, Dulcy! Though I do hope my opinion also shines through: love it!

I loved this post, Cliff — not only interesting, but so informative, too!! Really good stuff.

Thanks, Karen!

This is a fine, interesting article. I enjoyed reading it, and I look forward to reading more of your articles in the future.

By the way, I would like to invite you to join my blogathon, “The Great Breening Blogathon:” https://pureentertainmentpreservationsociety.wordpress.com/2017/09/07/extra-the-great-breening-blogathon/. It is celebrating the life and work of Joseph Breen, the enforcer of the Motion Picture Production Code between 1934 and 1954. As we honor his birthday, which is on October 14, we will be discussing and analyzing the Code era, breening films from other eras, and writing about our own ideas for classic movies. One doesn’t have to agree with the Code and Mr. Breen to enjoy that! I hope you will do me the honor of joining. We could really use your talent!

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan