Uptown New York stars Shirley Grey as a working class city girl who falls for an entrepreneurial blue collar fellow (Jack Oakie) while on the rebound from a young Jewish surgeon (Leon Waycoff).

They are three normal lives intertwined by life in a typical romantic melodrama of the era that only threatens censors when the surgeon, played by Leon Waycoff—later Leon Ames—seduces Grey’s working girl towards the beginning of the movie. This premarital dalliance does not lead to the pregnancy viewers might expect, but only heartbreak for both. Waycoff’s father soon toasts his son’s graduation and impending marriage to a Jewish girl already accepted by the family. Waycoff lacks the resolve to revolt against expectations and soon departs to Vienna where he embarks upon post-graduate work after his honeymoon. Back home, Grey finds herself locked in the bathroom of a Coney Island grill where she’s rescued by standoffish Oakie, who’d rather be eating his burger than pulling stranded girls out of bathroom windows. She sticks by his side that evening though, mostly so he can stay on one side of her and hide her torn dress, and they are soon in love. The working class pair seem ticketed for marriage until Waycoff returns from Europe, more established in his profession and more sure of himself, pleading for Grey to come back to him. Their reunion comes to a quiet resolution that finds Gray standing by her original intentions and next to Oakie at the altar. This is not the last time they’ll be thrust together though.

This is a cheap little Poverty Row film from director Victor Schertzinger made at Tiffany Studios for K.B.S. Productions and distributed through World Wide Pictures. In terms of modern accessibility, Uptown New York is a public domain title that I bumped into on YouTube, accounting for my grainy screen captures, and that you can pick up for six bucks or less from Alpha Video.

I had read that it owed a lot to Fox’s Bad Girl, a 1931 Best Picture nominee that did win two Academy Awards, including one for director Frank Borzage, and that is certainly true. Shirley Grey’s character in Uptown New York is similar to Sally Eilers’ in Bad Girl, and Oakie is even given a grating catchphrase (a snap of the fingers followed by “Check”) just like James Dunn had in the earlier film (Dunn swipes a hand from his head and the says, “Okay.”). The similarities go beyond character though to the very core of the two stories: each film features young couples whose relationships teeter because of a lack of communication. Both the Oakie-Grey and Dunn-Eilers couples are threatened by an independence that is traditional and expected in the male characters, while something relatively new for the female characters. These new women take their husbands at face value, while the men seem blindsided by wives who don’t react in familiar ways.

At first glance this makes Uptown New York seem like too much of a Bad Girl knock off to bother with. I assumed that World Wide just cranked out a similar script and told Schertzinger to do his best at mimicking Borzage on a much smaller budget. And maybe they did, but the similarities between the two movies are less attributable to directors Borzage and Schertzinger than they are their common source, author Viña Delmar. For me, the most rewarding feature of Uptown New York is that it pointed me towards finding out more about Delmar, a figure I had previously overlooked, even if I do have her 1928 novel Bad Girl placed among the hundreds of saved items in my Amazon shopping cart.

The changed economic position of woman has altered the whole social life in this country. And most of all the morals. The young people of today have the courage and initiative to mold circumstances to fit their needs instead of being controlled by Puritanical rules of conduct.

—Viña Delmar, 1928

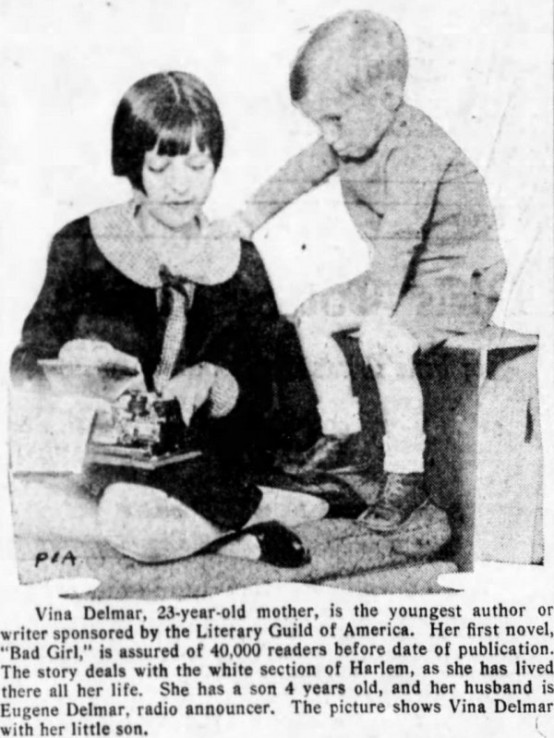

Today, Viña Delmar is best remembered as a screenwriter, primarily for two 1937 adaptations for Leo McCarey, Make Way for Tomorrow and, especially, The Awful Truth. The latter, on most short lists for greatest screwball comedy of all-time, brought Delmar her only Academy Award nomination. Her entire Hollywood career owed itself to her 1928 novel Bad Girl, which brought her a fame on par to that of Anita Loos for a few years: movies were sold on Delmar’s name, which was always prominent in the advertising. In fact, ads for Dance Hall (1929), the first film adapted from her writing, often didn’t feature images of the leading actors, but of young Viña Delmar and her black bobbed hair.

She was born Alvina Croter in New York in 1903. Her parents were vaudeville performers, and she seemed destined to follow in their footsteps. She married young, to Eugene Delmar, a radio announcer and writer, who gave Viña her last name and a good deal of editorial assistance. In a 1928 feature Delmar claimed she never finished grade school and boasted that “I’m not literary.” She said that before she published Bad Girl she only knew of one author, but began reading Theodore Dreiser before finishing her book. When she heard Dreiser was a realist, she just figured that’s what she was too. The author of that same article, James M. Neville, described Delmar’s writing technique, carried out with pencil and paper four nights per week:

She writes so swiftly in longhand that she leaves out prepositions, articles and so forth which are supplied by her husband, Gene. He types out the stories, makes all sorts of grammatical corrections, keeps people away while she works, offers suggestions for changes and not infrequently argues with her about the merits of a plot situation or character.

The actual writing was a collaboration, but the characters, stories, and ideas were all Viña Delmar. Despite a lack of formal education, Delmar’s wit and intelligence shines through her quotes, her modern ideas likely born of her non-traditional background and her own rise from what Neville described as the “tediously conventional section of uptown New York” from where she wrote Bad Girl.

Delmar was still a teenager when she caused her first stir in 1921 by placing an ad to rent her husband for $5,000. “Gene is a writer,” she said of her husband. “He writes lovely poems to me and wants to write other things. Of course, he couldn’t support us yet on writing.” She reproduced a mock conversation they had had about how they could support themselves, culminating in Gene suggesting that he sell himself. “Never, never!” Delmar said. “Not sell—but—maybe you might rent yourself out.” This was before Delmar began writing herself and the article described her as “the prettiest, cutest ‘little trick’ who ever tripped into a Broadway manager’s office.” She was probably still working with her family on the stage at this early date. This little stunt brought both Delmars nationwide publicity while at the same time raising a point about the financial struggles of young artists. There was no follow-up. Delmar eventually hunkered down to write Bad Girl, which shot her to immediate fame after the Literary Guild made it a book-of-the-month selection. Interest was further heightened after Bad Girl was banned in Boston, where it was claimed the book’s scenes of premarital sex potentially violated the Massachusetts obscenity law. Delmar, already feted as the youngest author ever selected for book-of-the-month, became a superstar.The changed economic position of woman has altered the whole social life in this country. And most of all the morals. The young people of today have the courage and initiative to mold circumstances to fit their needs instead of being controlled by Puritanical rules of conduct.

In the press she was always called “Bad Girl author Viña Delmar,” and remained so throughout the 1930s. After Bad Girl she continued cranking out similar stories of tenement life with suggestive titles like Up-Town Sheik, A Lady With Money, St. Louis Blues, and The Marriage Racket. Like all popular fiction authors of the time Delmar was serialized in several magazines and after her first flush of literary fame she even had some of her shorter work published as standalone stories in newspapers. Uptown New York originated as one of these early stories, appearing under the title Angie—Uptown Woman in the July 1928 issue of Redbook magazine, and was later included in Loose Ladies, a collection of Delmar’s short stories.

Other Delmar stories adapted to film in the wake of Bad Girl included Pick-Up (1933) with George Raft and Sylvia Sidney; Chance at Heaven (1933) with Ginger Rogers and Joel McCrea; Sadie McKee (1934), which saw the author’s name emphasized in promotion ahead of the star’s, Joan Crawford; and Hands Across the Table (1935) with Fred MacMurray and Carole Lombard. But by the time of Bad Boy (1935) at Fox, both Delmar and star James Dunn seemed to be grasping at the last strands of fame Bad Girl had brought them.

Viña Delmar had been a media darling from about 1928-1933, but it wasn’t just Uptown New York that had the taste of Bad Girl, almost all of her stories did, so Delmar’s reputation began to dim. She gained some press early in 1937 after tabbing Three Smart Girls star Barbara Read—none too coincidentally also one of the stars of Make Way for Tomorrow—“America’s Daughter.” It was an honorary title meant as the next in a line of better remembered nicknames such as “America’s Sweetheart” and the “It Girl.” Obviously that didn’t go so well. Delmar, in explaining the “America’s Daughter” label, announced a new era that attempted to separate her from her Bad Girl past, unfortunately, by denouncing it as just that, something past:

Around the Hollywood night clubs you still find occasionally some of the remnants of the ‘Bad Girl’ era. They are wistful, lonely and sad, and full of regrets. After all, every girl finds her greatest happiness in someday having her own fireside and children. They have muffed their opportunity.

Viña Delmar soon faded from the Hollywood scene, but she kept writing, publishing new stories and novels. She wrote some plays, including Mid-Summer, a 1953 comedy that featured hot property Geraldine Page in her Broadway debut. It was reported that Viña Delmar inherited $500,000 after her husband Eugene died in 1957, but even if that is the case neither the money, nor the loss of her long-time editor, caused her to slow down. She had always been known for contemporary stories like Bad Girl, but in the 1950s Delmar reinvented herself as an author of historical fiction. She remained an active novelist into the mid-1970s.

A few years after her husband died, their son, TV director Gray Delmar (who had directed one of his mother’s stories on stage in the 1950s), was killed in an automobile race on Long Island in 1966. Viña Delmar died in a Pasadena convalescent hospital in January 1990 at age 86. Her Los Angeles Times obituary mentions that she was survived by four grandchildren.

Now I can see Viña Delmar—the 1928 flavor—in my favorite scenes of Bad Girl: when James Dunn chats with Sally Eilers inside her apartment building. In addition to the boy-girl dynamic on those apartment stairs, other lives stir all around them causing Dunn’s character to comment on how much of a struggle life is for people of their class. Delmar is also found on the front stoop of Shirley Grey’s apartment in Uptown New York when Grey catches up with forlorn Jack Oakie to confess that Leon Waycoff had been more than a friend. “I don’t see much difference between marrying a man and merely living with him,” Delmar said. “From a purely social and legal aspect, however, marriage is the best thing—but not necessarily from a moral point of view.” Even at the height of her fame, Delmar distanced herself from the flapper label, insisting that she chronicled young women she knew, and very likely the young woman who she was.

The best scene of Uptown New York comes immediately after Oakie’s Eddie Doyle marries Grey’s Pat. Eddie signs the hotel register and asks for a quiet room. All seems well when they’re assigned the bridal suite, but that’s only the best room in what turns out to be a dive with paper walls. A party rages next door to the bridal suite, its noise spoiling any chance of romance between the newlyweds. Too distracted for any physical spark, Pat gives in to second thoughts and sits Eddie down to explain her past relationship with Max, the doctor, to him. “We were very much in love, Eddie,” she says, clarifying for the first time just how involved she had been with Max. Then she offers him an out: “We’re not really married, Eddie,” she says, hearkening back to Delmar’s comments about morals and marriage. “If you want to, we could call it quits, I’d understand.” Pat looks forlorn as Eddie remains silent. He moves across the room to the phone, surely to check out and demand a refund, but instead he yells at the clerk on the other end of the line, demanding he silence the party next door. Pat runs to Eddie, hugs him, and buries her face into his shoulder to cry. Eddie accepts her as his wife, unconditionally. There’s no scene like this in Bad Girl, and it helps Uptown New York establish its own identity.

Both movies, Uptown New York and Bad Girl, show how a lack of communication can cause selfless acts to look like selfish acts. This idea boils through to the climax of both, though in this case Bad Girl offers the more rewarding drama with its story centering around the birth of the couple’s first child. Uptown New York, on the other hand, drops any pretense of subtlety leading to its finish by having Pat dash into the middle of the road where she’s mowed down by a truck. Just as the child’s birth in Bad Girl creates a series of misunderstandings that bring the couple’s relationship to a boiling point, Pat’s accident in Uptown New York does the same by necessitating the return of a certain doctor.

Uptown New York released in late 1932. Variety called it a “weak attempt to follow up ‘Bad Girl,’” an understandable appraisal at the time. Both then and now, Jack Oakie’s surprisingly effective dramatic performance is cited as the highspot of the movie, and he does excel throughout. It’s an interesting performance with a hint of Oakie’s lighter, more typical characters often visible, but almost always plastered over by disappointment and other realities of life. Leon Waycoff is appropriately sturdy in what reminded me of a poor man’s John Boles role. Shirley Grey wasn’t the revelation that Oakie was, but I found myself liking her Pat character more than I did the part that Sally Eilers played in Bad Girl. Especially after looking into Viña Delmar. Grey seemed to be cast as a slightly more evolved version of the same character, more self-assured and independent, more the finished woman. Eilers had the cuter lines in the earlier movie, but after Waycoff’s character leaves her most of the cute and perky is knocked out of Grey’s Pat.

As far as pre-Code era independent productions, Uptown New York isn’t in the class of my favorite, The Sin of Nora Moran, but secures itself in the next tier. Most of the indie stuff from this period is poorly made, shamelessly derivative, and often an effort to enjoy, but don’t sneer at Uptown New York just because it lacks a major studio logo.

Finally, speaking of that logo, if World Wide’s is meant to set the mood, I certainly got a lot more than I expected out of Uptown New York after being greeted by this:

References

- “‘Bad Girl’ Achieves Boston Blacklist.” Reading Times. 4 May 1929, 28.

- “Movie ‘Bad Girls’ Reform.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 2 Mar 1937, 12.

- Neville, James M. “Youth Emancipated With Big ‘E’ Says Viña Delmar.” Columbus Evening Dispatch. 30 Sep 1928, 91.

- “Novelist Gets Half Million.” Janesville (WI) Daily Gazette. 20 Dec 1957, 17.

- “Rush Is Made to Rent Hubby at Five Thousand Per Year.” New Castle Herald. 21 Jun 1921, 9.

Thank you for reviewing this often-ignored, amazing pre-Code movie, which is all the more amazing when one considers that it was a low-budget indie film instead of a studio masterpiece. Pre-code movies are fascinating anyway, and often have unexpected endings, making them more interesting than the formulaic post-code movies. I think this one was a little gem, even if it was a low-budget remake of the earlier Dunn version.

I was especially impressed by this example of Oakie’s ability to give a fine dramatic performance. There were a few other shining dramatic and part-dramatic roles for him in his career, but it’s very rare that the studios ever allowed him to be anything but a comedian. It’s been said that comedians are actually among the best of the fine dramatic actors, and while that may not be true in all cases, it’s certainly true in his case. There is no question that his sensitive performance was absolutely fantastic, and very memorable.

Leon Waycuff-Ames is totally forgettable in his own role – he could have been exchanged with any number of other young handsome actors of the day. He never gave the role anything distinctive. Actually, I thought the doctor comes across as weak and selfish, even a cad. He didn’t even TRY to stand up for his “true love” against his parents – he gave in without a murmur. He didn’t even seem to be terribly heart-broken about having to give up Pat. This all made him very unlikable in my estimation, especially when contrasted to the unselfish Eddie who was willing to give up everything he’d worked so hard for in order to pay for Pat’s operation, and even step aside from the marriage if that was what Pat wanted.

Shirley Grey was enjoyable, although I didn’t get the impression that her Pat was in love with Eddie when they married – it seemed to me to be more of a ‘rebound’ situation, although it was clear that she actually did fall for him after she realized what a selfless man he actually was, and how lucky she was to have someone like him after her doctor dumped her. It took her long enough to realize it. She clearly had feelings for Eddie before the ending, but it seemed to take Eddie’s sacrifice to really make her realize how much she cared for him.

Your review has made me curious to see the James Dunn 1931 version, as well. I’d be interested to compare the two. Both being pre-Code, it would be even more interesting than usual. (Post-code remakes tend to be very washed-out.)