Helen Vinson specialized in playing calculating society beauties. He characters forever plotted to get what they wanted, usually wealth, by giving up as little as possible.

Completely capable of playing sympathetic roles, such as she did in I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (1932) and Trans-Atlantic Tunnel (1935), the versatile stage actress was almost immediately typed upon Hollywood arrival after causing so much trouble as Constance Bennett’s sister in Two Against the World (1932), just her second film. Vinson’s characters were typically well-monied, like the actress herself, or trying to recapture a lost lavish lifestyle. She played ice princesses of the highest order, teasing her way towards fortunes, though usually the hero wised up before completely falling victim to her, as did Edward G. Robinson in The Little Giant (1933). Spencer Tracy was not as successful at fending off Vinson in The Power and the Glory (1933).

Some of Vinson’s best roles came out of type, including a couple of my favorites, Midnight Club (1933) and, more recently, The Wedding Night (1935). The first film is a fun romp that casts Vinson as Clive Brook’s girlfriend and fellow thief. They, along with mob member Alan Mowbray, play dual roles as part of a crime twist that leaves undercover dick George Raft baffled through most of the film. In The Wedding Night, subject of the next review I post, Vinson threatens more of her usual routine by coming out of the gates as Gary Cooper’s nagging wife, but a more complicated relationship develops between the two as the movie progresses and Cooper falls for Anna Sten’s immigrant character.

Some of Vinson’s best roles came out of type, including a couple of my favorites, Midnight Club (1933) and, more recently, The Wedding Night (1935). The first film is a fun romp that casts Vinson as Clive Brook’s girlfriend and fellow thief. They, along with mob member Alan Mowbray, play dual roles as part of a crime twist that leaves undercover dick George Raft baffled through most of the film. In The Wedding Night, subject of the next review I post, Vinson threatens more of her usual routine by coming out of the gates as Gary Cooper’s nagging wife, but a more complicated relationship develops between the two as the movie progresses and Cooper falls for Anna Sten’s immigrant character.

Talking about one of her earlier films, Second Hand Wife (1933), Vinson said, “I’m so bad that I almost twirl mustaches. If I had a whip, I’d have shamed Simon Legree” (Keavy). After another half dozen or so heavy parts, you can almost hear the wistfulness of her tone when she said, “It is only human to want to be liked, so after a certain length of time the knowledge that you inspire only disgust and loathing in all who see you, begins to ‘get under your skin’ and you become very unhappy” (Richards).

Vinson was born Helen Rulfs in Beaumont, Texas on September 17, 1905 (or ‘07). Her father, Edward Anton Rulfs, was born in Germany, but made a success in the United States as an oil man with the Texas Oil Co. Helen’s mother, Lillian, was Texas born and bred. I had a difficult time piecing together the Rulfs family genealogy, but I came across one sparse mention of Helen adapting Vinson as her stage name because it was her mother’s maiden name—I couldn’t disprove it with an alternative story, so I’m willing to believe it for now (Parton).

Vinson was born Helen Rulfs in Beaumont, Texas on September 17, 1905 (or ‘07). Her father, Edward Anton Rulfs, was born in Germany, but made a success in the United States as an oil man with the Texas Oil Co. Helen’s mother, Lillian, was Texas born and bred. I had a difficult time piecing together the Rulfs family genealogy, but I came across one sparse mention of Helen adapting Vinson as her stage name because it was her mother’s maiden name—I couldn’t disprove it with an alternative story, so I’m willing to believe it for now (Parton).

While Helen was young the Rulfs moved to Houston, where all of the later press about Helen’s wealthy upbringing is corroborated by her appearances in the Houston Post society columns. She was very active in the arts when young, playing an instrument with the “Junior Music Study Club” and attending Miss Settle’s dancing classes in Houston throughout the latter part of the 1910s. Young Helen Rulfs even won a dollar as fourth prize in the Post’s 1917 essay-contest, “Why Our Country Is At War.”

By 1921 sixteen-year-old Helen became involved with the Little Theater Guild in Houston. As one of twenty-five members of the Guild she found herself cast as the lead character’s daughter in a performance of Percival Wilde’s The Confessional and then in a much smaller part in an April 1922 staging of Within the Law. Despite the brevity of that role Helen still managed notice in the Post, who reported, “Miss Helen Rulfs, though having the small part of a sales girl in the Emporium, brought tears of sympathy to the eyes of the audience in her helplessness.” A few weeks later Helen was cast in the lead of Alice Duer Miller’s comedy Charm School.While attending the University of Texas at Austin Helen was one of eight young women selected as a “Bluebonnet Belle” by Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. The honor landed her an impressive full-page portrait in the annual yearbook, the Cactus (reproduced below).

On May 27, 1925 Helen married Harry Nelson Vickerman, a Philadelphia carpet manufacturer, at the Christ Episcopal Church in Houston. The Vickermans returned to Philadelphia where Helen began acting for East Coast stock companies. At the end of 1927 she landed a part in her first Broadway show, Los Angeles, a George M. Cohan production starring Alison Skipworth, who Helen later worked with in both Midnight Club and The Captain Hates the Sea (1934).Helen Vinson didn’t make it back to Broadway until 1931, when she replaced Rose Hobart in the lead of Death Takes a Holiday. Between Broadway and the subsequent road show Helen played that part for thirty weeks. Neither Berlin nor The Faithful Alibi were as successful, but as Helen recalled, “My big chance came in the guise of Fatal Alibi with Charles Laughton, which show led me to Hollywood and the screen” (Richards).

Her first movie role was as Kay Francis’ sidekick in the hilarious and romantic Jewel Robbery (1932) at Warner Bros. That was harmless enough, but then she went and ruined Constance Bennett’s life in Two Against the World, and the mold was set.

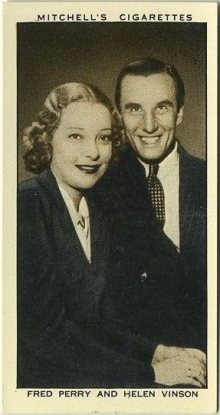

“My marriage had crashed before I went to Hollywood,” Helen said around the time of her February 1934 divorce from Vickerman. The two separated in March 1932—when Helen left for Hollywood—and Helen testified that he constantly nagged her because he didn’t want her to be an actress. Her mother was also present in court and added that Helen was always upset and run down during her time living with Vickerman. Helen told Screenland journalist Kay Richards that she had no plans to marry again.But Helen never appeared in the press more than she would during her second marriage, to tennis star Fred Perry. When they were married Perry was considered the greatest tennis player in the world, having recently won his second of three consecutive Wimbledon championships. They met when Helen became one of the first of a wave of Hollywood actors to take on movie work in Great Britain. “If we both hadn’t happened to sail on the Berengaria for England, probably we never would have met,” Helen told Modern Screen in 1936. While in England working for Michael Balcon at Gaumont-British, Helen appeared in Trans-Atlantic Tunnel and King of the Damned (both 1935). She later returned for Love in Exile (1936) and to meet up with her husband, who had stopped over on business in Australia.

Helen and Perry grabbed four friends in Manhattan on the night of September 12, 1935 and raced to Harrison, New York. There, like you’d see in an old movie, they roused the town clerk from his bed to issue the license and secured a justice of the peace to marry them at 11:55 pm, beating a midnight deadline that would have otherwise placed their anniversary on a Friday the 13th! Despite this effort luck didn’t last very long for the celebrity couple.

Helen and Perry grabbed four friends in Manhattan on the night of September 12, 1935 and raced to Harrison, New York. There, like you’d see in an old movie, they roused the town clerk from his bed to issue the license and secured a justice of the peace to marry them at 11:55 pm, beating a midnight deadline that would have otherwise placed their anniversary on a Friday the 13th! Despite this effort luck didn’t last very long for the celebrity couple.

Helen sued for divorce in December 1938 claiming that Perry had refused to accompany her to parties and neglected other social responsibilities. Once, when she was ill in England, he refused to allow her to sail back to New York where she could be attended by the Rulfs family physician. The final straw came when Perry cursed her while demanding she cancel a scheduled radio interview.

Helen continued working through 1941 when she left Hollywood and speculated on the potential of a soybean farm in Virginia. It cost her $40,000 and, after the war consumed all available manpower, her own time and labor. Neighbors referred to her as “Missy Helen, the moving picture star,” and got a kick out of listening in on the party line whenever Hollywood or New York called for Helen. “Every time I received a call from New York or Hollywood, I guess everyone rushes to the phone,” she said. “You can hear crying babies and dropped pots and pans from miles around” (Johnson).

She returned to Hollywood for a handful of films, her last the penultimate Thin Man entry, The Thin Man Goes Home in 1945. The following year Helen married Donald J. Hardenbrook, a wealthy investor and member of the New York Stock Exchange, who later became president of the National Association of Manufacturers.

She returned to Hollywood for a handful of films, her last the penultimate Thin Man entry, The Thin Man Goes Home in 1945. The following year Helen married Donald J. Hardenbrook, a wealthy investor and member of the New York Stock Exchange, who later became president of the National Association of Manufacturers.

Helen retired from films for good and later, when her husband was Association president, traveled the country to keep him company and lend support. In the mid-1950s she busied herself at their summer home on Nantucket Island. Originally built in 1750, the Hardenbrooks fully restored the home and furnished it with early American antiques. Helen decorated herself utilizing her lessons learned while attending the New York School of Interior Design for three semesters a few years prior to their buying the house. In addition to those classes she also studied French for four years at the French Institute in New York, where the Hardenbrooks maintained a presence through 1971, when they moved to Nantucket full-time.

Donald Hardenbrook died in 1976 at age 80. Helen Rulfs (Vinson) Hardenbrook died of natural causes in a Chapel Hill, North Carolina nursing home October 7, 1999 at age 94 (possibly 92).

Above: Helen Vinson with her parents, Edward and Lillian Rulfs. Found in Screenland, July 1935, page 66.

References

- Ancestry.com. North Carolina, Death Indexes, 1908-2004 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007.

- “Benefit for Y.W.C.A. And Guild Fund Greeted By Big Audience.” Houston Post. 9 April 1922, 20.

- “‘Charm School’ Next Program of Little Theater.” Houston Post. 26 April 1922, 11.

- “Donald Hardenbrook, 80, Ex-Head of N.A.M., Dead.” New York Times. 9 July 1976.

- “Essay on ‘Why Our Country Is At War.’” Houston Post. 23 December 1917, 38.

- “Fred Perry, Net Star, And Helen Vinson Wed.” Mount Carmel Item. 13 September 1935, 1.

- “Galveston Girl a Bluebonnet Belle.” Galveston Daily News. 27 May 1923, 7.

- Hall, Leonard. “Fair Exchange.” Screenland. July 1935, 33-34, 66.

- “Helen Vinson Chooses Career Over Husband.” San Bernadino County Sun. 9 February 1934, 20.

- “Helen Vinson Sues for Divorce From Perry.” Santa Ana Register. 7 December 1938, 8.

- “Houston Society.” Galveston Daily News. 24 May 1925, 15.

- “Husband, Si! Movie Career , No!” Kansas City Times. 1 November 1962, 13C.

- Johnson, Erskine. “In Hollywood.” San Jose Evening News. 28 October 1943, 14.

- Keavy, Hubbard. “Screen Life in Hollywood.” Scranton Republican. 8 November 1932, 19.

- “Little Theater Guild Gives First Trio of Playlets.” Houston Post. 18 December 1921, 16.

- Mastin, Milded. “A Lady in Love.” Modern Screen. June 1936, 42, 109.

- Parton, Lemuel F. “In the Spotlight Today.” Salt Lake Tribune. 31 August 1935, 4.

- “Perry, Australia Bound, Leaves Wife in Hollywood.” Pottstown Mercury. 16 October 1935, 7.

- Richards, Kay. “Don’t Brand Her ‘Society Girl!’” Screenland. July 1934, 33, 80-82.

Very informative bio, Cliff! Really enjoyed all the interesting info you dug up on her.

Best wishes,

Laura

Thanks, Laura! I’ve always been a fan, but just had to write about her after I saw The Wedding Night, which I just posted a review of now—hopefully, you’ve got one coming too!