The Barrymore brothers share the movie screen for the first time in Arsène Lupin, a March 1932 release from MGM. John and Lionel’s top notch individual performances elevate an already solid mystery, while their skillful and competitive play off one another prove a delight for fans pulled to the film by any curiosity of seeing the legendary brothers working together.

The Barrymore brothers share the movie screen for the first time in Arsène Lupin, a March 1932 release from MGM. John and Lionel’s top notch individual performances elevate an already solid mystery, while their skillful and competitive play off one another prove a delight for fans pulled to the film by any curiosity of seeing the legendary brothers working together.

“Sometimes it is quite certain that Guerchard, the police chief, played by Lionel Barrymore, is the daring thief Arsène Lupin, but on other occasions one feels sure that the Duke of Charmerace (John Barrymore) is the criminal.”

So wrote Mordaunt Hall in his contemporary New York Times review of the film, though today the identity of the gentleman thief seems obvious. Still, you may foster a nagging doubt as you watch, so I won’t divulge Lupin’s identity either, though I will say that I wish the film had managed to cash in on that little tinge of doubt.

I viewed Arsène Lupin not so much as a whodunit, but a howdunit. The mystery relates less to Lupin’s identity as it does making that identity stick in order to lock up the criminal, once and for all.

Arsène Lupin was created by French writer Maurice Leblanc, who originated the character in 1905 and published numerous stories and novels featuring his gentleman thief through the 1930s. The character was on film several times previous to this production, dating as far back to 1908, though this was the first talkie version of Lupin. This 1932 adaptation was loosely based on a play co-authored by Leblanc and Francis de Croisset that was soon novelized in their native French and then translated into English by Edgar Jepsen. That Jepsen edition was published in the U.S. by Doubleday in 1909.

The Jepsen translation retains all of the characters found in the film, as well as the basic situation of the threat of Lupin hanging over the ill-gotten treasures of Gourney-Martin. Tully Marshall is more of a presence as Gourney-Martin in the film than the character is in the book, and while the Duke of Chamerace falls for Sonia in the novel, she too is a more minor character on the page. The relationship as played out between John Barrymore and Karen Morley in the film is superior, highlighted by playful banter and sexy flirtation throughout.

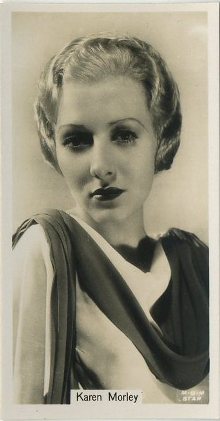

While John and Lionel strive to out-do one another, Morley, as usual, takes us by surprise in Arsène Lupin and more than holds her own alongside the legendary brothers. She had just worked with Lionel in Mata Hari (1931), and was advancing rapidly during her first full year in Hollywood. Within a few months of Arsène Lupin’s release, audiences could next see Morley in the film that she’s best remembered for today, Scarface (1932), opposite Paul Muni.

While John and Lionel strive to out-do one another, Morley, as usual, takes us by surprise in Arsène Lupin and more than holds her own alongside the legendary brothers. She had just worked with Lionel in Mata Hari (1931), and was advancing rapidly during her first full year in Hollywood. Within a few months of Arsène Lupin’s release, audiences could next see Morley in the film that she’s best remembered for today, Scarface (1932), opposite Paul Muni.

In Arsène Lupin, Karen Morley lays claim to one of the greatest screen entrances of the pre-Code era. When John Barrymore, as the Duke of Charmerace, opens his bedroom door he discovers her in his bed, completely naked except for the blanket she grips over her chest. After a brief moment recovering from the shock of his entrance, her Sonia is calm, friendly, even welcoming. Discounting that blanket she is completely comfortable in nothing more than her own skin.

The Duke and Sonia speak so familiarly to one another that it is a surprise to discover they are only meeting for the first time. After a few moments of teasing, Sonia finally says, “I assure you, being here is no pleasure.” The Duke, with all of the lechery implied simply by having Barrymore cast in the part, practically sings in reply, “But the night is young.”

The flirtation between Sonia and the Duke remains steady throughout Arsène Lupin, and even though they barely know one another any better than we know them, they are so immediately and intimately bonded that you almost feel uncomfortable witnessing them playfully volley such private barbs and innuendo.

That teasing never slows down. Once they join the Duke’s guests in his ballroom, Sonia’s insistence on dancing causes him to comment, “You can’t relax, even in bed, can you?” Later, at Gourney-Martin’s after Guerchard leaves them for a moment, the Duke asks, “Do you want to go back to your solitaire? Or would you prefer something that requires two people?” Sonia is charmed by the Duke and even after she becomes convinced that he is Lupin, she maintains hope that he is first and foremost a gentleman. When the Duke grows too bold with his advances, she says she believes Lupin would steal anything, but adds, “I don’t think he’d ever take anything from a woman, that she wasn’t willing to give.” The Duke takes her hint and backs off.

That teasing never slows down. Once they join the Duke’s guests in his ballroom, Sonia’s insistence on dancing causes him to comment, “You can’t relax, even in bed, can you?” Later, at Gourney-Martin’s after Guerchard leaves them for a moment, the Duke asks, “Do you want to go back to your solitaire? Or would you prefer something that requires two people?” Sonia is charmed by the Duke and even after she becomes convinced that he is Lupin, she maintains hope that he is first and foremost a gentleman. When the Duke grows too bold with his advances, she says she believes Lupin would steal anything, but adds, “I don’t think he’d ever take anything from a woman, that she wasn’t willing to give.” The Duke takes her hint and backs off.

The dialogue between John and Lionel is every bit as playful, only their game is cat and mouse.

The film opens with a robbery at the house of Gourney-Martin. Evidence points to Arsène Lupin, notorious thief whose freedom is the only blight on the career of the otherwise celebrated Detective Guerchard. When Guerchard arrives at the crime scene he discovers a man tied up in the back of a car claiming that he’s been held up and robbed. The victim claims he is the Duke of Charmerace.

Guerchard is certain that this so-called Duke is actually Arsène Lupin himself. With the Duke secured in handcuffs, Guerchard remains smugly satisfied that he has indeed captured Lupin, until Gourney-Martin arrives and immediately identifies the man in handcuffs as the Duke of Charmerace.

“Nobody but a doddering ass would think I was Arsène Lupin,” says the Duke as Guerchard removes his handcuffs and stutters a bit in apology.

From there the game persists. The mysterious Arsène Lupin continues to threaten Gourney-Martin, while Detective Guerchard’s suspicion of the Duke heightens and the Duke sticks close to both Guerchard and Gourney-Martin, to feed his own wild curiosity about the case of Lupin.

After the identity of Lupin is revealed beyond doubt, the remainder of the action, concerning the theft of the Mona Lisa, is entirely original to the movie. The idea wouldn’t have occurred to Leblanc or anyone else before 1911, when the painting achieved mainstream celebrity status as a result of its actual theft. The crime is the ultimate cherry on top of Arsène Lupin, as it’s an even more audacious act by Lupin than the ransacking of Gourney-Martin’s ill-gotten collection. While the theft of the painting does clash with Lupin’s Robin Hood image, it’s worth noting that the real thief claimed patriotic impulses led to his stealing the painting and, in the movie, Lupin only takes possession momentarily with plans of using the painting as leverage to free his underlings.

One area where Leblanc’s novel surpasses the film comes in the actual revelation of Arsène Lupin’s identity. As I mentioned, it’s not a great surprise in the movie, which provides several other treats instead. Not so in Leblanc’s story, where the reader is practically as enthralled as the Duke of Charmerace by the details of the case until a later chapter suddenly builds to a surprisingly suspenseful standoff unmasking Lupin through a bold bit of dialogue that seemingly comes out of nowhere. But no matter how suspenseful that scene reads, it absolutely cannot match the tension created simply by matching one Barrymore against another as the movie does.

Despite this dream bit of casting, MGM originally conceived this version of the film as a vehicle pitting John Gilbert against Lionel Barrymore, with Tod Browning slated to direct. Browning instead wound up on Freaks, which filmed at the same time as Lupin during an especially productive time at the studio that also yielded The Beast of the City and Tarzan, the Ape Man. Jack Conway directed Arsène Lupin instead. On September 19, 1931, Motion Picture Daily announced that Gilbert had suddenly quit Arsène Lupin to embark on a European vacation, and before the month was out it was announced that John Barrymore, who had just completed his contract with Warner Bros., would be coming to MGM to play in Arsène Lupin opposite his brother.

Arsène Lupin was the first of five features that John and Lionel Barrymore worked together, all released in 1932 and ‘33 by MGM. Up next, they bonded more closely in Grand Hotel’s all-star cast, and then they were teamed with sister Ethel in Rasputin and the Empress, the only time all three Barrymores worked together on film. Next came another classic all-star production in Dinner at Eight, the best of the films the brothers both appeared in, despite their not even sharing a scene together. I don’t know how MGM resisted the temptation! They would share several scenes in their final effort together, Night Flight, but that all-star effort misfired because it kept most of the other stars apart from one another. Almost all of Night Flight’s best scenes are those shared by John and Lionel.

But the novelty was fresh with Arsène Lupin and it led to endless speculation over which brother gave the best performance. I’d probably give the nod to John, whose scenes with Karen Morley often outdid even those with Lionel. When the brothers weren’t together, Lionel had moments to shine alongside John Miljan, who played the Prefect of Police, and Mary Jane Irving, who’s on hand briefly (mercifully) as Guerchard’s daughter. But for all the talk about the brothers, I wouldn’t argue with anyone who made a case of Karen Morley stealing the film. I don’t think she quite does that, but she certainly holds her own with each of the Barrymores playing a character whose own mysteries are revealed before Arsène Lupin comes to an end.

My thanks to Warner Archive for providing a review copy of their recent manufactured-on-demand DVD-R Arsène Lupin Double Feature – Pick up your copy here. All accompanying screen captures were grabbed from my copy of that Warner Archive disc. The two-film set also includes Arsène Lupin Returns (1938), which I’ve reviewed previously on Immortal Ephemera and even more recently (and more favorably) on WarrenWilliam.com.

Be sure to check out Danny Reid’s post about Arsène Lupin at Pre-Code.com. It’s so good that I actually put off writing about this title for awhile so I could be sure I didn’t unintentionally mimic any of his thoughts!

Be sure to check out Danny Reid’s post about Arsène Lupin at Pre-Code.com. It’s so good that I actually put off writing about this title for awhile so I could be sure I didn’t unintentionally mimic any of his thoughts!

I was surprised by how hard I had to dig to find reviews of Arsène Lupin on other classic movie blogs. Actually, Danny links to both of these too, but here’s Angela at The Hollywood Revue with a favorable write-up and Michael N. at Stars in Heaven: An MGM Blog with a less complimentary view, though he did like the Barrymore pairing. This 2012 article by David Kalat at TCM’s Movie Morlocks site is a great read, but none of the images or videos showed up for me, which made it a bit messy. Still, worth the time. And, if you’d prefer to go back in time, here’s Mordaunt Hall of the Times again.

Sources

- “John Barrymore’s Next Under the M-G-M Banner.” Film Daily, September 28, 1931, 1.

- “John Gilbert to Quit for Europe.” Motion Picture Herald, September 19, 1931, 11.

- Mordaunt Hall, “John and Lionel Barrymore Engage in Battle of Wits in Film Version of ‘Arsène Lupin,’” New York Times, February 27, 1932.

- Simon Kuper, “Who Stole the Mona Lisa,” Financial Times, August 7, 2011.

Thanks for the kind words, Cliff! I really struggled with my review since I didn’t want to reveal too many jokes or the twist either– even though it’s not exactly that big of a twist either way. I think the thing I admire most about Arsene is how modern it still feels, and how it builds to a really clever climax. It’s very funny film, too. Did you ever do a review on Arsene Lupin Returns, either here or at the Warren William site?

You’re welcome, Danny! I told you at the time I loved that post, I really had to stay away from it for awhile until I finished this one up!

Definitely a tough one to approach without revealing too much, especially since the movie more or less reveals everything itself. But then, there were those tacks in the shoes and the little lingering doubts they cast, so I tried to play along.

Also agree about the modern feel, I think Morley deserves a lot of that credit. Without her this could have felt stale. And with a lesser talent in her part, say someone at the level of the actress who played Lionel’s daughter, the whole thing would have crumbled. While I say above I didn’t think she actually stole the movie from the brothers, I think she saves it from being a lot less than it may have been otherwise.

Yes, I covered Lupin Returns in both places actually! They’re linked near the bottom of the post, but you’ll find the more recent write-up at my Warren William site here.