Richard Dix is a strange subject. Beyond some health issues, a costly IRS entanglement and a well-publicized divorce from his first wife, his overall biography is a lot tidier than many of his peers. He was a popular figure around Hollywood and one of his sons, who would carve out his own Hollywood career, is still around and quick with a kind word about Dix as father and family man. When discussing Richard Dix the most interesting thing to talk about is Dix the actor.

Richard Dix is a strange subject. Beyond some health issues, a costly IRS entanglement and a well-publicized divorce from his first wife, his overall biography is a lot tidier than many of his peers. He was a popular figure around Hollywood and one of his sons, who would carve out his own Hollywood career, is still around and quick with a kind word about Dix as father and family man. When discussing Richard Dix the most interesting thing to talk about is Dix the actor.

His screen legacy is hugely diminished from what it once was. Richard Dix came to his first and overall greatest prominence as a silent film actor but that makes for a tough sell today. He enjoyed his most lasting fame in an acclaimed talkie that has since become one of the more unappreciated of all Academy Award Best Picture winners, and that’s by people who’ve bothered to see it at all. He appeared in approximately fifty other movies throughout the 1930s and ‘40s, and he starred in most of them. But those movies came mostly from RKO and, later “B” work both there and at Columbia, during a time most usually celebrated with examples of MGM glamor or Warner Bros. grit.

He starred in several entertaining films for RKO prior to enforcement of the Production Code and while some of those are now gaining more exposure than since the time of their original release, none of them really fit the mold of the typically sexy and censor-daring pre-Codes that are most popular today. Today, Dix’s talkie career is most recognized by fans of the Western genre while his later work appeals to film noir fans, but he is an actor whose reputation suffers by these more narrow labels. He especially suffers when associated with any single title because while Dix’s biggest films have their fans, they also have their detractors.

He starred in several entertaining films for RKO prior to enforcement of the Production Code and while some of those are now gaining more exposure than since the time of their original release, none of them really fit the mold of the typically sexy and censor-daring pre-Codes that are most popular today. Today, Dix’s talkie career is most recognized by fans of the Western genre while his later work appeals to film noir fans, but he is an actor whose reputation suffers by these more narrow labels. He especially suffers when associated with any single title because while Dix’s biggest films have their fans, they also have their detractors.

In the best light Richard Dix was a capable actor who appeared in movies of every genre over a long career that saw him ascend to major stardom in both silent and sound films. He is best appreciated as a sum of many parts.

Biography – Part 1

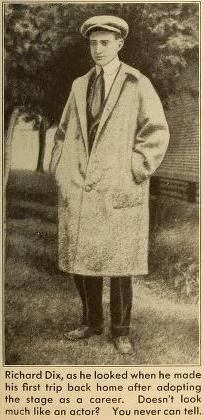

Richard Dix emerged from what I’ve come to consider the most fascinating generation of actors, but the path his movie career followed included a significant twist from the norm. Born Ernest Carleton Brimmer in St. Paul, Minnesota, July 18, 1893, Dix was of the generation that came of age during the First World War. Dix did not serve in the war effort himself claiming an exemption to support his parents and sister.

In film historian Dan Van Neste’s book The Whistler: Stepping Into the ShadowsBy the time of the war young Richard Dix already had theatrical experience in stock companies and even on Broadway, where he made his debut in The Hawk in 1914. By 1916 Dix was a member of Oliver Morosco’s Los Angeles stock company. While on the coast Dix appeared in his first film, W. Christy Cabanne’s One of Many (1917), starring Frances Nelson. Dix played the butler in this five reel production released by Metro and had enough of a part to garner (positive) mention in the period reviews.

After One of Many Dix disappointed himself in screen tests he undertook for Cecil B. DeMille scenarist Jeanie MacPherson and also for pioneering female director Lois Weber. Dismayed by how poorly he had tested Dix was happy when his stock work took him back to New York, where he wound up staying long enough to appear in three plays during 1918-19. One of the shows Dix appeared in was the farce I Love You written by William LeBaron, who Dix later worked for at both Paramount and RKO. Dix downplayed his time on Broadway writing that association with LeBaron “was perhaps the biggest thing I got out of the stay in New York” (Dix).

After One of Many Dix disappointed himself in screen tests he undertook for Cecil B. DeMille scenarist Jeanie MacPherson and also for pioneering female director Lois Weber. Dismayed by how poorly he had tested Dix was happy when his stock work took him back to New York, where he wound up staying long enough to appear in three plays during 1918-19. One of the shows Dix appeared in was the farce I Love You written by William LeBaron, who Dix later worked for at both Paramount and RKO. Dix downplayed his time on Broadway writing that association with LeBaron “was perhaps the biggest thing I got out of the stay in New York” (Dix).

While many of Dix’s contemporaries spent the 1920s climbing the heights of Broadway, he went back west at the start of the decade and became one of the silent cinema’s most popular stars over the next several years. Appearing in films for the Goldwyn Corporation and then Paramount, Richard Dix quickly soared to stardom in films such as The Christian (1923), which served as his breakthrough role; The Ten Commandments (1923), a Cecil B. DeMille title that offered some redemption for the earlier screen test experience; The Vanishing American (1925), his most famous silent role; sports titles like The Quarterback (1926), Knockout Reilly (1927) and baseball film Warming Up (1928), which was advertised as Paramount’s first sound film (score and sound effects, but no dialogue).

Above: Richard Dix graces the cover of Motion Picture Classic’s October 1924 issue. Illustration by Alberto Vargas. Discovered via Lantern Search Engine as are most other vintage magazine images and references on this page.

His handsome features and youthful dash earned him spots on the covers of popular movie magazines, a space usually reserved for the most glamorous actresses of the day. In a 1926 popularity poll sponsored by Motion Picture Classic, one of the most popular of those fan magazines, he even outdistanced Rudolph Valentino in the final tally among actors. That result was repeated among film exhibitors and their families in a 1929 tally that named Dix and Paramount stablemate Clara Bow the winners of a “My Favorite Players” contest.

Richard Dix was a gigantic star of the silent screen. And then came sound.

Talkie Transition

Actors of Dix’s generation generally followed one of two paths during this turbulent period. The Hollywood coffers were opened to those who had stuck on Broadway because, after all, their voices were a major part of their appeal and earning power. The new arrivals pushed out the silent stars whose voices didn’t make the grade with their previous employers. Richard Dix, despite having spent most of the 1910s on stage, even as a Broadway headliner, found himself among those being pushed.In his Whistler book Dan Van Neste chronicles the late 1920s as a tumultuous period for Dix personally and professionally. The actor found himself at odds with his Paramount bosses after they were reluctant to cast him in his first talkie and despite a 1928 raise that made him the studio’s highest paid star, the promise of better films that came with the pay hike did not develop. Dix’s first two talkies, Nothing But the Truth and The Wheel of Life (both 1929) were disappointing films that even caused Dix’s voice to be criticized by the press who had previously been strong supporters.

“Seeing yourself in your first talking picture is a terrible sensation. I saw my picture for the first time the other night and I was in an absolute daze the rest of the night. I got some sort of a queer sensation the first time I saw myself on the screen but that was increased tenfold when I heard my voice as well,” Dix told Hollywood journalist Dan Thomas in 1929. When Thomas asked him what he considered the most important quality for an actor in the new type of film, Dix remained hopeful as he basically described himself: “There are many things which must be combined to make a good actor and of course voice is now one of them. But I believe I would still rank personality and acting ability first. I believe that if an actor gives a good enough performance he can make his audience forget what deficiencies there may be in his voice.”

“Seeing yourself in your first talking picture is a terrible sensation. I saw my picture for the first time the other night and I was in an absolute daze the rest of the night. I got some sort of a queer sensation the first time I saw myself on the screen but that was increased tenfold when I heard my voice as well,” Dix told Hollywood journalist Dan Thomas in 1929. When Thomas asked him what he considered the most important quality for an actor in the new type of film, Dix remained hopeful as he basically described himself: “There are many things which must be combined to make a good actor and of course voice is now one of them. But I believe I would still rank personality and acting ability first. I believe that if an actor gives a good enough performance he can make his audience forget what deficiencies there may be in his voice.”

Just ahead of those first couple of talkies, Dix suffered through his first major health troubles when complications from a 1928 appendectomy created headlines casting him as the next Valentino: “Richard Dix May Follow Path of Valentino: Film Star Close to Death.”

It may be hard to imagine Dix being so newsworthy today, but after his rise beginning with The Christian in 1923, Dix had since cemented his status as a legend of the silent screen when he starred as a sensitive Native American in the 1925 classic The Vanishing American.

The Vanishing American

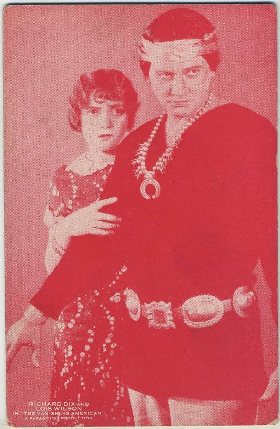

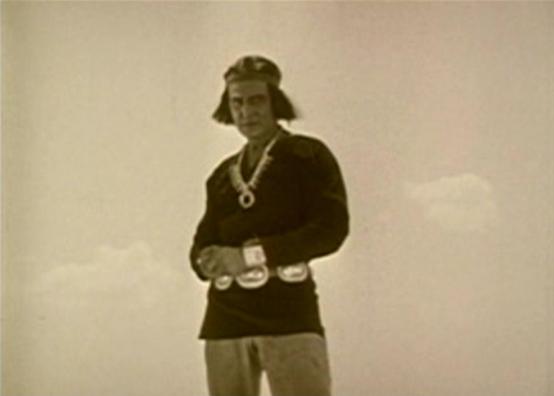

This well-meaning blockbuster of 1925 features Dix as Nophaie, respected war chief of an early 20th Century Native American tribe on a reservation that featured Monument Valley as its backdrop.

It’s actually a little over a half hour before Richard Dix appears in the film, his arrival following a prologue that featured some imagined Native American history and prehistory up until reaching present day when the Indians were controlled on reservations by the American government. Dix as war chief is a peaceable man. The local Indian agent is a pawn of troublemaker Booker (Noah Beery), a villain of the first order, who takes advantage of the Indians at every turn. Lois Wilson plays a teacher, or perhaps more accurately missionary, Miss Marion Warner, who Nophaie comes to love. Dix is very tender towards Wilson in their scenes together.

When the army sends Earl Ramsdale (Malcolm McGregor) West to procure horses for the war effort, Miss Warner seems to fall for him, but even so Nophaie emerges to secure the required horses and pledge himself and several brothers for war duty. “Pitiful — and tremendous! Riding away to fight for the white man!” says Ramsdale to Miss Warner while Nophaie leads his troops away.

Nophaie was a tailor-made role for Dix, who would have been much more believable cast as a Native American in 1925 than he appears today. Dix, as usual, presents a rough exterior: He is a warrior and the Dix face requires little more than a stern expression to carry off such a label. But his war chief is also a man of peace. He knows when to push and when to abide the law of the white man with hopes of gaining eventual acceptance. His Nophaie is a gentle man who makes what would then be accepted as the proper moral choices throughout the film. Miss Warner is his beacon, and when he departs for war he carries her with him tangibly in the form of a copy of the New Testament that she gifts him. It, like Miss Warner, is all that is good and right and Nophaie comes to believe in it’s word over the gods of his tribe.

The film does a good job in showing the struggles of Nophaie and his people and their mistreatment by the whites who oversee them and their land. It also sugarcoats that treatment by presenting them as just the latest in a long line of conquering peoples who are later displaced by another set of conquerors. Of course, this implies that the current powers-that-be could one day face such a challenge as well, but I think the main message they were striving for in 1925 is that Indians are people too and, don’t worry, they shall assimilate if given the opportunity to do so.

Whether you find The Vanishing American damaging or simply dated it is easy to understand how audiences were captivated by Dix’s performance as the heroic Nophaie.

But Nophaie and the past success of The Vanishing American had absolutely no bearing upon Richard Dix’s standing when talkies arrived and Dix’s voice was deemed poor. After his first talking feature for Paramount rumors surfaced that Dix would make one more film for the company before jumping ship to the newly formed RKO, where his old friend William LeBaron served as head of production. Ironically, Dix’s third talking feature for Paramount, The Love Doctor (1929, it’s worth noting that the IMDb has the wrong release date), which wasn’t released until after Dix went to work for RKO, earned raves from Film Daily, who called it “one of the best comedies of the year.”

But Nophaie and the past success of The Vanishing American had absolutely no bearing upon Richard Dix’s standing when talkies arrived and Dix’s voice was deemed poor. After his first talking feature for Paramount rumors surfaced that Dix would make one more film for the company before jumping ship to the newly formed RKO, where his old friend William LeBaron served as head of production. Ironically, Dix’s third talking feature for Paramount, The Love Doctor (1929, it’s worth noting that the IMDb has the wrong release date), which wasn’t released until after Dix went to work for RKO, earned raves from Film Daily, who called it “one of the best comedies of the year.”

William LeBaron, who had written one of the plays Dix had appeared in on Broadway and been associate producer on a few Dix films at Paramount, was then head of production at RKO, a studio sorely in need of stars. In May 1929 Dix signed with the company and began his talkie comeback with his first RKO starring feature, Seven Keys to Baldpate (1930). Dix received good write-ups for this and subsequent RKO titles Lovin’ the Ladies and Shooting Straight (both 1930, the latter including a Farnesbarnes reference), each of which were written by J. Walter Ruben, who would soon direct Dix in some of his best movies of the period. While Dix was still on his initial short term deal with RKO, the studio bought the rights to Edna Ferber’s Cimarron (1931) and cast Dix in the lead.

Cimarron

Cimarron cost a fortune to make and actually wound up losing money, but it was enough of a critical and popular success to secure Dix a lucrative new contract at RKO paying him $50,000 per film for five films per year with additional payments of 12-1/2% of the net proceeds from each title (Van Neste 170).

Today Cimarron is typically cast aside and labeled as dated. Since the film is a historical epic following Dix and company from the end of the 19th Century through present-day 1930 the label applies mostly to production values and especially Dix’s performance, which can be awkward. Dated may also be a bit of a euphemism for racist, though Eugene Jackson’s treatment as Isaiah is typical of the period but more generally known because of Cimarron’s enduring status as an Academy Award-winning Best Picture. Confusing matters is the great empathy the Dix character has for the Native American people of the film, a trait I assume comes directly from author Edna Ferber because of a resemblance seen on the screen years later in George Stevens’ Giant (1956), also based on a Ferber novel. Yancy Cravat’s general empathy towards the Indians does pair this one nicely with Dix’s earlier work in The Vanishing American.

As for Dix, he may still be relying a bit too much upon 1910s stage experience by the time of Cimarron, but his Yancy Cravat does emerge as a fascinating character. He’s a patriotic figure who is hellbent on taking part in America’s expansion in aid of history rather than taking advantage of easy situations that present themselves to him for personal gain. Dix fits Yancy’s white hat and always believes he’s on the side of what is good and what is right. He’s loving towards his wife, Sabra (Irene Dunne), but puts adventure ahead of family and disappears for long stretches to do what he believes is right for country because, at heart, what is right for country is right for family. His revolver carries several notches, most earned in earlier times but put on display for us a couple of times, including an exciting battle against Yancy’s old running-mate, The Kid (William Collier, Jr.).

Dix is at his best in the many action sequences, but also during the quiet moments of Cimarron, when the actor’s better nature shines through Yancy. His performance suffers in Yancy’s more boisterous moments and the proud Yancy has enough of those for us to notice.

I like Cimarron and find it improved with each viewing. That seems to be a quality of Dix, an actor who sort of grows on you with additional exposure. His work can seem stiff, and sometimes it might be, but the more you absorb of Richard Dix the more you’ll find formerly wooden qualities begin to soften. Dix is more star than actor, generally playing different versions of “Richard Dix” on screen rather than offering a unique creative vision to each character. He’s a tough looking fellow with a steel jaw who is easily believable in his action roles, which are many. Excepting his later work he often plays very moral heroes that despite the rough exterior are often made gentle by the often subdued Dix. His characters often earn our empathy through a very measured delivery of his lines that make Dix’s words almost soothing to the viewer.

A Bit More Biography

While Richard Dix had completed his comeback in grand style, receiving his only Academy Award nomination and at least securing film immortality as star of a Best Picture winner in Cimarron, 1931 wasn’t all sunshine for the actor. The Internal Revenue Service sued him for back taxes owed on the years 1927 and ‘28 with Dix appearing in court just after Christmas and being ordered to pay $100,000 penalty: “I left my taxes up to one of these experts, and here I am. It’s the first time I’ve ever been in trouble. In fact, I never was in court before in my life” (’Richard Dix Pays…’).It was during this year of ups and downs that bachelor Dix surprised Hollywood with his marriage to socialite Winifred Coe in October 1931. A daughter was born in January 1933, but even a newborn couldn’t save the rocky marriage which was dissolved in a quickie Mexican divorce that same June. While initial reports called the split amicable, the ex-Mrs. Dix made things a bit messier when she later pursued and received a heftier settlement from her former husband.

Dix’s second marriage came soon after his split with Coe, but it was far more successful union. Around the beginning of 1934 Dix hired a new secretary, Virginia Webster, whose main task would be to answer the star’s voluminous fan mail. Hollywood was surprised by Dix all over again when a June 30, 1934 Associated Press report passed along the news that Dix had married his secretary the previous day in Jersey City, New Jersey. The location was selected for “purely romantic reasons,” according to Dix, who informed the press that his new bride’s parents had been married in the same place 25 years earlier (’Richard Dix and His Secretary’).Virginia soon resigned her post as secretary and the following year gave birth to twin sons, Richard and Robert Dix. The couple later adopted a daughter, Sara Sue, in 1942.

Robert Dix, who later forged his own successful Hollywood career appearing in films such as Forbidden Planet (1956) and Forty Guns (1957), continues to keep his father’s legacy alive today.

In 2008 he published his memoirs, Out of HollywoodRKO Post-Cimarron

While Cimarron returned Richard Dix to the apex of stardom it also became a tough act to follow. Ads for subsequent movies touted the star of Cimarron!, while reviews for the same movies reminded people that every Dix movie couldn’t be another Cimarron.

My own favorite era of Richard Dix movies come during this period. Dix starred in several forgotten titles at RKO over the next few years and nearly every one that I have seen has far exceeded expectations. Several have been covered on the site, and those past articles are linked at each mention, with more to follow soon. The movies I’m referring to are titles such as The Public Defender (1931), The Lost Squadron, Roar of the Dragon, Hell’s Highway, The Conquerors (all 1932), No Marriage Ties, Ace of Aces, Day of Reckoning (all 1933), Stingaree and His Greatest Gamble (both 1934).

The better known titles from these early ‘30s Dix films generally hold their status for reasons other than Richard Dix: Erich von Stroheim plays a director in a supporting role in The Lost Squadron; Hell’s Highway is the chain gang film that was released before the more famous I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang; William A. Wellman directed The Conquerors, a generational saga that more closely resembles Cimarron than any other Richard Dix title; Wellman also directed Stingaree, but that one is more thought of as an Irene Dunne vehicle than it is associated with her Cimarron co-star Dix.

These four movies alone are a strong showcase of Dix during the period, as you’ll see him bring his talents to four very different parts. But I like Ace of Aces a little better than any of the others.

Ace of Aces

Dix comes off as a bit pompous at the start of Ace of Aces. President Wilson has just declared America’s entry into the World War and Dix, as sculptor Rocky Thorne, only wants to continue work at his studio. When fiance Nancy Adams (Elizabeth Allan) shows up in her Red Cross uniform and beams over the soldiers marching past below, Rocky shakes her by comparing them to lemmings marching to their deaths on a command with consequences that they don’t even understand. Nancy is appalled by Rocky’s superior attitude and while Rocky insists that he’s keeping out of the fight because of scruples and conscience, Nancy calls him a coward. She leaves in a huff while Rocky skulks up the steps of his scaffold to continue work at his sculpture.

We can see that her words have pierced through him and, sure enough, the next scene finds Rocky arriving at his barracks overseas.

The bulk of Ace of Aces finds Rocky in Europe where he begins as a nervous new recruit but quickly develops into a feared ace pilot who shoots down record numbers of German planes. Rocky’s development is best illustrated by his chosen mascot, a mostly harmless lion cub that emerges from a picnic basket upon his arrival but which grows into a dangerous looking beast that is later seen sprawled out on the floor alongside a more experienced Rocky. A pair of killers.

I plan to delve further into Ace of Aces sometime soon when I review a copy of the recently released Made-on-Demand DVD-R from Warner Archive.

What matters for now is Dix’s performance. He’s perfect as Rocky Thorne, that gentle, soft-spoken manner appropriate for his Rocky the pacifist, but from the moment of his first confirmed kill a menace carves itself across Dix’s rough features and turns him into the most terrifying character he ever played. This man who once molded life becomes obsessed with causing death and glories in the credit that comes with his success in the air. When Nancy meets up with him later in France she is startled by the changes that have come over the man she once loved. Dix enjoys the most caddish moment of his career in this scene and Nancy, perhaps feeling responsible for this new man or maybe just caving to the pressures of war, succumbs to his loutish advances. Rocky eventually reels himself in but a relapse caused by his competitive nature nearly proves fatal.

Ace of Aces wobbles some in its final scene, but it’s an entertaining film that is highlighted more than any other Dix movie by the actor’s performance. It also seems to have stuck with Dix as his character in the later Men Against the Sky (1940) was touted as the “ace of aces” on more than one occasion throughout that film.

More Cowboys and Aces

Dix signed a new short-term contract with RKO in 1934 and appeared in a couple of Westerns, West of the Pecos (1934) and The Arizonian (1935), before being recruited by Michael Balcon to star in Transatlantic Tunnel in London for Gaumont British. This bizarre title has proved popular over the years and features familiar Hollywood faces such as Madge Evans and Helen Vinson plus guest appearances by Walter Huston and George Arliss. Dix stars as the head of an international effort to built a tunnel between England and America.

When Dix returned to America he finished his commitment to RKO with Yellow Dust (1936) and Special Investigator (1936). In March 1936 Dix signed a long-term contract with Columbia, but shifted back to RKO in 1938. During this period Dix starred for RKO B unit director Lew Landers in Blind Alibi, Sky Giant (both 1938) and Twelve Crowded Hours (1939), and later appeared in what was probably his most effective film of the period, RKO’s Reno (1939), a Cimarron-like tale of a man’s part in building the Western city, told in flashback in a courtroom setting by an aging version of the Dix character.

Dix also freelanced during the early 1940s, mainly in Westerns, including several produced by Harry Sherman for Paramount, but as his health began to fail him he found the genre a bit too demanding. While it would be crude to call high blood pressure and the onset of the heart trouble that would eventually kill him (Van Neste 180) any kind of blessing in disguise, the change in screen fare for the veteran actor did lead to some of his strongest parts in years.

The Ghost Ship

I prefer Dix’s work in The Whistler series that followed, but it was his performance in the Val Lewton produced The Ghost Ship for RKO in 1943 that led Harry Cohn to cast him in that later Columbia series.

The calm Dix demeanor was used to great effect in The Ghost Ship, which saw him cast as a soft-spoken overly philosophical ship’s captain who is somewhat quickly discovered to be a killer by new third officer Tom Merriam (Russell Wade). At the end of their first meeting Captain Stone politely scolds Tom for thinking of killing a moth, remarking that Tom holds no sway over the moth’s destiny. Soon the bodies mount and the Captain not only does not deny his hand in the murders when questioned by Tom, but reverses the logic of the moth in explaining that as Captain he is responsible for the fate of his men. “Men are worthless cattle and a few men are given authority to drive them,” he claims.

The Ghost Ship’s inclusion in the Val Lewton DVD boxset and TCM Lewton marathons has caused it to be among Dix’s most seen films over the past decade or so. While it is far from the typical Richard Dix performance it’s a bit of a shocker for someone who comes to the film after already being familiar with Dix—that would have been everybody in 1943. For the experienced Dix viewer it is interesting to see his kinder screen qualities turned upside down as his calm and quiet demeanor mask a murderous intensity that eventually has to boil over.

The Inevitable End of Biography

Columbia’s Harry Cohn was impressed by what Dix had done in The Ghost Ship and offered him The Whistler (1944). Cohn is legendary as a bully and a tyrant as studio head, but those few voices that spoke in his favor always seem to do so strongly. Apparently Dix would have been one of them. According to son Robert Dix, “My father liked Harry Cohn and Mr. Cohn had a high regard for him” (Van Neste 182).

Dix’s final film in The Whistler series, The Thirteenth Hour (1947), would unfortunately turn out to be his final movie appearance of any kind. In the Fall of 1946 he suffered his first heart attack while playing tennis with son Robert. He soon stepped away from acting and lived a quiet life in semi-retirement. Two years after his first heart attack, in late 1948, Dix fractured his hip in a fall and suffered a second heart attack which led to his being put in a sanitarium to recover. In the Van Neste book Robert Dix describes his father as becoming resigned to the inevitable and fondly recalls the time they spent together during this late period (183). Dix eventually received doctor’s permission to accompany his family on a vacation through Europe, but he suffered yet another heart attack on the cruise back home. It was tough-going just for Dix to get back home as failing health held him over in Chicago for four weeks, but in September he was finally able to fly back to Hollywood.

At 9:00 on the morning of September 20, 1949 Richard Dix had a cardiac collapse. According to his doctor, “He was conscious to the last spasm, a gamester who wanted to live. He fought for life courageously but his reserves were too depleted. He smiled at Mrs. Dix and at 10:10 he passed away” (’Dix Battled’). Hollywood mourned the loss of Richard Dix just two days after the passing of popular character actor Frank Morgan.

At 9:00 on the morning of September 20, 1949 Richard Dix had a cardiac collapse. According to his doctor, “He was conscious to the last spasm, a gamester who wanted to live. He fought for life courageously but his reserves were too depleted. He smiled at Mrs. Dix and at 10:10 he passed away” (’Dix Battled’). Hollywood mourned the loss of Richard Dix just two days after the passing of popular character actor Frank Morgan.

Cimarron will likely always stand as the key piece to the Dix legacy due to the stature of the Academy Awards and the continued celebration of all movies sharing its historical link. I’d argue that it is not the best representation of Dix. While I enjoyed The Vanishing American and even The Ten Commandments, I don’t think it’s realistic to judge him by just his silent work either. It’s just too out of vogue and not the best way for him to acquire fans in the 21st century. Richard Dix is best enjoyed by the sum total of his work, not any single film, and given the renewed availability of so many of his titles from the 1930s and ‘40s he’s owed a reappraisal.

Sources and Citations

- “Dix Battled Stubbornly To Live, Doctor Relates.” Miami Daily News 21 Sep 1949: 6-B. Web. Google News. 24 Jun 2014.

- Dix, Richard. “How I Broke Into The Movies.” Deseret News 18 May 1932: 2. Web. Google News. 27 Jun 2014.

- Jewell, Richard B. RKO Radio Pictures: A Titan Is Born

Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012.

- “Richard Dix and His Secretary Wed.” Lewiston Daily Sun 30 Jun 1934: 1. Web. Google News. 24 Jun 2014.

- ”Richard Dix Is Sued.” Pittsburgh Press 24 Dec 1931: 11. Web. Google News. 24 Jun 2014.

- “Richard Dix Pays $100,000 Penalty for Tax Evasions.” Gettysburg Times. 29 Dec 1931: 2. Web. Google News. 24 Jun 2014.

- Thomas, Dan. “Richard Dix Is Told His Voice Isn’t Hot.” The Citizen (Ottawa). 10 May 1929: 10. Web. Google News. 24 Jun 2014.

- “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/KZVJ-8VY : accessed 29 Jun 2014), Ernest C Brimmer, 1917-1918; citing Los Angeles City no 9, California, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d); FHL microfilm 1530907.

- Van Neste, Dan. The Whistler: Stepping Into the Shadows

Albany, GA: BearManor, 2011.

Superb article on Richard Dix. My first exposure to him was THE WHISTLER series; it was an above-average “B” series and allowed Dix to flex his acting muscles. He was very good in it. It was interesting to learn that Lewton’s THE GHOST SHIP earned Dix that gig. Starting with his last films, I had to catch up on some of his earlier, more famous one and still haven’t seen many that you covered. But you have now provided me with an excellent, well-researched road map.

Thanks so much, Rick! I love The Whistler, been catching up with them ever since I wrapped up the research phase of this post. It’s no secret that I’m partial to early ’30s films in general, but most of those pre-Code Dix titles probably would have been able to be released after Code enforcement. They’re just good movies and since you’re already sold on Dix I’m pretty sure you’ll enjoy them. Thanks again!

Speaking of Richard Dix this Thursday July 3 if you get GETTV they going show back to back whistler movie start 7pm est 4pm pst

Hi Kelly, There’s also some rarely shown Dix on TCM in early July – The Marines Fly High on July 2 and, my favorite, Ace of Aces on July 11 — I hope to have my Ace of Aces post up by the time it airs.

Yeah I know I got Aces of Aces set up as dvr yeah I think because they doing WW1 100 anniversary as topic of the month

Check out Gettv schedule for July 3 it ready mark on their schedule

Wonderful to see Richard Dix being given his due in such a delightful and well-researched article, Cliff. I too am a big fan of “The Lost Squadron”–and find Dix to be a really compelling actor–in part because of his style of emoting and the unexpected humor he injected into many of his roles. Thank you for taking the time to do this splendid piece.

Moira, thanks again for your comment and the nice push you gave the post on Facebook. Much appreciated! He seemed like a “swell guy” that brought a lot of himself to his roles.

Very nice, in-depth profile of the underappreciated Mr. Dix. I heartily agree with your conclusion that the totality of his work is more impressive than one film or two films he made. When writing The Whistler, I was a bit surprised and terribly impressed by his filmography which included films of all genres. As you say, his work merits a reevaluation. Thank you for citing the book as one of your sources. I’m honored!

Dan, thanks for checking out my post and thanks again for providing all of the info that you do in your book — my copy has been taking a beating during my recent months of Dix-mania! By the way, can you point me anywhere towards a copy of The Great Jasper? Your glowing remarks over it in the book have turned me obsessive and I just can’t find it being offered anywhere!

I have just been pointed here via Laura’s Miscellaneous Musings blogsite. This is a superb biography of Richard Dix, Cliff. I was first introduced to Dix as a child in the 1950s when a couple of his Pops Sherman westerns were aired on UK TV. He appealed straight away. Since then I have seen many more of his films, in particular the fine “The Whistler” series.

Great job. Many thanks for the superb work involved.

Pleased to meet you, Jerry, thanks for coming over. Laura’s a great pal, love her site and our Twitter chats! I just caught the Sherman flicks recently: Was expecting less, got more. Seems to be the way with Dix. I really enjoy the Whistlers myself, I think they’re superior to the more heralded The Ghost Ship (better acting from the supporting cast; better sets; better overall to look at). I’d been wanting to do this post for awhile now because my instinct is that most people only see him in Cimarron and then write him off. I thought Cimarron okay at first and then by the time I saw more and more Dix I returned to it and enjoyed it much more. Anyway, thanks so much for the kind words, so glad you enjoyed the post!

Sorry for the late reply: excellent biographical information here!

It’s news to me that his voice was deemed poor for talkies. I think he’s one of only a few whose voice actually matched his silent screen presence: that pleasant baritone that can be whimsical or stern. Hmm.

I watched Redskin and Seven Keys to Baldpate again last night, and enjoyed his last silent and fourth talking film. The latter is, despite being stage-bound, one of the better early talkies that I’ve seen, and Mr. Dix’s performance certainly comes across a lot better than other silent stars who were still emoting too much or didn’t cross that barrier that left behind the beautiful world of silents very well. Nothing Buth the Truth, his first talkie, is certainly a good one, too, for how early it was (April 1929 release).

Three more things: John Gilbert gets credit for that “I love you, I love you” line, but Mr. Dix uttered that several months before in The Wheel of Life (July 1929). I wonder how that went over?

I love when he “loses it” in The Ghost Ship, or is likewise quite fiendish in several of the Whistler films. In the former, after a whole career of playing the hero, how satisfying it must have been to really stretch his acting chops and show a side that few stars ever get to portray, and do it very well.

That imdb goof about the Love Doctor needs to be fixed. That’s bothered me for years. The film exists at UCLA, thankfully.

Hi Jon, thanks for the great comment!

It’s funny, other than The Ghost Ship you’ve run down a bunch of Dix titles that I have not seen yet–though I just picked up the set with Redskin and am looking forward to watching it soon! I think the earliest Dix talkie I’ve seen is Lovin’ the Ladies and I’ve seen most after that with the exception of threemovies at Columbia with ‘Devil’ in the title. Got to grab copies of those soon!

I like what he does in The Ghost Ship, though I think he’s better in the Whistler series. Either way, I agree, love to see him go to dark places, so unexpected from an actor whose greatest asset prior to that was his likable charm.

I’m sure Dix’s voice was just fine, but I bet the equipment didn’t do him any favors. Hollywood really was in love with Broadway voices and seemed to look past a lot of talent that was already hard at work for them. Paramount seems especially guilty, thinking of their jettisoning Wallace Beery too.

Thanks again for chiming in!

Cliff

I’ve just found this post, probably via discussion of TCM’s Dix tribute this week, but I confess, I’m not sure exactly how I got here. In any case, I wanted to add my thanks and compliments on this post. It was thorough, thoughtful, and interesting. I’ve watched a number of early 30s Dix films: I finally got to see Cimarron when TCM showed it awhile back. As a fan of the Whistler radio series, I sought out the movies, as well. Thanks to your pointer, I’m looking forward to reading the Dan Van Ness book. Thanks again for a great post.

Thanks for the kind words, Shelly, glad you found me! I’m looking forward to getting to some of those Dix movies on my DVR, this week’s TCM marathon actually filled in a few holes in my own Dix viewing. Oh, if you’re a fan of The Whistler, you’re going to love Dan’s book. It really includes about everything you could think of, Whistler-related. Have you seen Ace of Aces? I think that’s Dix’s best myself and have been preparing myself to cover it for a few months now … really want to do it proper justice!

Have been a Richard Dix fan for many years. His early talkies don’t seem to suffer as much, as many of the

others do, from stagnant direction, and an isolated camera. His quiet intensity, is a welcome change from the

almost cartoonish quality of actors in the period. I’ve been glad to see the “Whistler” films, since they’ve been

featured on GetTV, among the Columbia library. Watching that dark persona, in those movies, has reminded

me of today’s anti-heroes, who are often a mixture of good and evil. He was actually blazing a new trail for the actors of the period. It’s great to see a site that celebrates these largely unexplored treasures from the

past!

Thanks, Dave! Dix is a favorite and continues to pop up on the site—he’s even featured in my most recent review about Special Investigator. Thanks for your kind words about the site too!

This is a terrific article, Cliff. Richard Dix is a favorite of mine, and I am pleased to see him getting his due somewhere!

Thanks, Scott! Yes, also a favorite of mine, sturdy leading man who takes some time to grow on you.