I was once again interrupted from working when I came across a full page autobiographical article by Thomas Mitchell in the October 15, 1939 edition of Screen & Radio Weekly. I’d been curious about Mitchell for awhile, yet had never previously taken the time to get to know him better, so this article offered the perfect opportunity.

The article was published during Mitchell’s banner year, a banner year for all of movie history, 1939, for which Mitchell deserves more recognition than the footnote status he seems relegated too. In that single calendar year he figured in five major releases, all of which still hold exalted status: Stagecoach, for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role; Only Angels Have Wings; Mr. Smith Goes to Washington; Gone With the Wind; and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which was the film discussed as his current release at the time of this article.

What’s amazing beyond the quality of Mitchell’s ’39 is its’ variety and extending beyond that single year variety seems to be the overriding ingredient to Thomas Mitchell’s career as a whole. He was much more than a character actor, more than an actor in fact, he spread his talents across several different areas of the stage and screen.

Born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, July 18, 1892, Mitchell writes that he came out of high school with two possible career paths: acting and journalism. His father and brother were newspapermen, and so that’s the path he first chose. Mitchell says he went to work for his brother John, then managing editor of the Newark Journal, before spending “a few minutes” with the Baltimore Sun. Washington and Pittsburgh garner mention as other journalism stops, but “while I liked the life, I didn’t like the money … The theater beckoned.”

Mitchell entered theater with hopes of combining his loves of writing and acting and claims to have launched himself through a vaudeville sketch he wrote and performed about teen-aged 18th Century poet Thomas Chatterton. He doesn’t mention the title and seems to have little recollection except the subject writing “How long it ran I cannot now recall. It served to get me launched.”

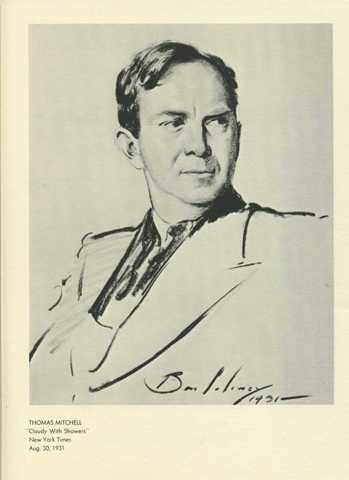

Mitchell traversed the East and Mid-West playing in stock companies including Charles Coburn’s company. He made it to Broadway through Shakespeare with the Ben Greet Players, recalling “…when Shakespeare moved on, I stayed. I stayed through luck.” He worked his way through one bit part after another eventually earning the lead in The Wisdom Tooth in 1926. Next he collaborated on the script for Glory Hallelujah of which he admitted “The play was a flop, closing after several weeks. But what of that? The thrill remains. I can still feel it.” Mitchell was very proud of the fact that Glory Hallelujah brought Lee Tracy to prominence.

Having established himself as a competent playwright with Glory Hallelulah, Mitchell would continue his dual role as writer-actor in 1928’s Little Accident and 1931’s Cloudy With Showers. Next he spread himself out even more:

About this time, too, I must have thought I was a triplet-sitter, for when Fate offered me a third chair I clamped down on it, too. I began directing. And I kept at it for five years.

While dismissing his single silent film appearance in 1923’s Six Cylinder Love from Fox, Mitchell looks back on the Frank Capra classic Lost Horizon (1937) as his debut on the screen. While he would appear to moviegoers in a handful of releases prior to Lost Horizon, including the popular Irene Dunne vehicle Theodora Goes Wild (1936), Capra’s Horizon was actually the earliest Hollywood film featuring Mitchell to go into production, in March 1936.

At the time of his 1939 article Mitchell remained very happy with his decision to leave Broadway for Hollywood. He writes:

“D’you know, when I look back on that period now, I realize it was a good thing I finally quit. I’ll tell you why. An actor needs somebody over him, some constructive critic. But when an actor is his own director…well, in that case, he is like a boxer trying to get along without a sparring partner…I realized finally that whatever acting ability I possessed was beginning to suffer because I was my own director, so I quit it. You can’t sit on too many chairs at once.”

Beyond being relieved of his many hats, Mitchell claimed the screen gave him a “more expansive canvas on which to work. It enable me to round out a fuller characterization.”

Mitchell spends the last 20 percent or so of the piece discussing his current work, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and praising his co-star Charles Laughton. As I’ll largely be drawing on various obituaries to complete this profile it’s worth noting that Mitchell died of cancer, December 17, 1962–two days after cancer claimed Laughton’s life (though the period obits all report that it was a single day).

In Hollywood Mitchell rekindled his friendship with John Barrymore, whom he’d previously shared the stage with in 1918’s Redemption, and would later find himself the last survivor of the Bundy Drive Boys, the famed group of hell-raisers that besides Barrymore included Errol Flynn, W.C. Fields, and writer Gene Fowler who put them to print in Minutes of the Last Meeting (1954).

Mitchell kept busy after his busy 1939 appearing in Our Town and The Long Voyage Home in 1940, Out of the Fog in 1941 as well as The Devil and Daniel Webster in which he was replaced by Edward Arnold in the Daniel Webster role after fracturing his skull in an on-set carriage ride; Moontide, a bit in Tales of Manhattan, and swashbuckling in The Black Swan through 1942; patriarch of The Sullivans in 1944, a year in which he also appeared in biopics Buffalo Bill and Wilson, plus The Key to the Kingdom; beloved Uncle Billy in holiday classic It’s a Wonderful Life in 1946.

In the late 40’s Mitchell split his time between the screen and a return to the stage where he played Willy Loman in the national tour of Arthur Miller’s A Death of a Salesman. In the early 50’s Mitchell became a regular face on television which led to 3 Emmy nominations including a win in 1953, the same year he’d win a Tony Award on Broadway as Best Actor in a Musical in Hazel Flagg, based on the 1937 William A. Wellman film Nothing Sacred.

Thomas Mitchell’s final film would come working under the same man who directed his first talkie, Frank Capra, in Capra’s 1962 remake of his own Lady for a Day (1933), Pocketful of Miracles starring Bette Davis with Mitchell reprising the Judge role originally played by Guy Kibbee. Diagnosed with a cancer a year prior to his passing, Mitchell kept busy until the very end appearing on The Perry Como Show the night before Thanksgiving (in an episode filmed the previous summer).

[phpbay]thomas mitchell, 16, 45100, “”[/phpbay]

Often a little zany, sometimes a little drunk, Mitchell’s appearance on the screen always bumps a film up a few notches. Though I forever picture him tying strings around his fingers as Jimmy Stewarts foolish Uncle Billy in It’s a Wonderful Life, he’s just as effective when things turns serious such as they did after Cary Grant grounded him in Only Angels Have Wings or when a very nasty John Garfield pursues Mitchell’s daughter, played by Ida Lupino, in Out of the Fog.

While the three chairs Thomas Mitchell occupied at one time on the stage are mostly lost to current generations beyond photos and period reportage, he appeared in a total of nearly 60 films, many of which survive, many of which have always been with us simply because of their stature.

My own five favorite Thomas Mitchell roles:

- 5. Jonah Goodwin in Out of the Fog (1941)

- 4. Tommie Blue in The Black Swan (1942)

- 3. Doc Boone in Stagecoach (1939)

- 2. Kid Dabb in Only Angels Have Wings (1939)

- 1. Uncle Billy in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

Yours?

[…] claimed in a 1939 article that he cut his teeth by touring vaudeville with a once act play he’d written about the poet […]