Louise Brooks stars in William Wellman’s Beggars of Life (1928)

When Turner Classic Movies (TCM) was airing films from William Wellman last Wednesday night, I’d mentioned in another space that the scenes where the youths ride the rails in “Wild Boys of the Road” (1933) really reminded me of Wellman’s hobo silent* film “Beggars of Life” (1928). It’d been awhile since I’d watched the earlier picture though, so I dusted off my copy of “Beggars of Life” from Grapevine Video and did just that. I wasn’t let down.

When Turner Classic Movies (TCM) was airing films from William Wellman last Wednesday night, I’d mentioned in another space that the scenes where the youths ride the rails in “Wild Boys of the Road” (1933) really reminded me of Wellman’s hobo silent* film “Beggars of Life” (1928). It’d been awhile since I’d watched the earlier picture though, so I dusted off my copy of “Beggars of Life” from Grapevine Video and did just that. I wasn’t let down.

*Apparently Paramount added a sound sequence featuring Wally Beery singing, presumably the first shot of him we see in “Beggars of Life,” but this print from Grapevine seems to be the current standard and it’s not included. Additional note, the Arlen and Brooks’ characters are billed only as “The Boy” and “The Girl” in what I watched, though apparently they do have actual names, Jim and Nancy. Since this piece is based upon what I saw, they’ll be referred to here as “The Boy” and “The Girl.”

“Wild Boys of the Road” is a picture about tramping teens during the Great Depression adapted by Wellman from a story by Daniel Ahearn. In contrast “Beggars of Life” is a movie about a pair of young adults tramping among hard-edged hoboes prior to the Depression which Wellman adapted from a Jim Tully story. Tully was quite an interesting character himself, a successful author who rose from the same type of background depicted in “Beggars of Life.”

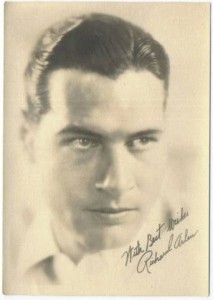

The film stars Richard Arlen as “The Boy” and Louise Brooks as “The Girl” with Wallace Beery as the main foil, Oklahoma Red. While Arlen’s acting skills seem to get hammered by numerous sources, including Brooks herself, I thought he did a credible job here of showing us a world-weary yet youthful tramp. Beery is Beery, I mean, he’s so familiar now that I could pretty much hear his voice throughout “Beggars of Life.” Brooks, whose reputation today far surpasses what it was then, really earns her exalted status here through a performance filled with subtle expressions and realistic gestures—my favorite example coming after Arlen and her are booted from the first train they stowaway on. While they slink away, unsure of their next step, Brooks commands the camera’s attention by doing nothing more than fetching half a sandwich out of her pocket for Arlen.

The opening of “Beggars of Life” is absolutely phenomenal and we’ll have a look at it in greater detail in a moment. The middle of the picture is fascinating, absorbing today’s viewer through its vivid depiction of hoboing, which practically plays as documentary (though it’s interesting to note that the New York Times period review stated that Wellman “reveals but little intimate knowledge of his subject“ and that “in the final analysis the film gives one no absorbingly interesting incidents connected with the hoboes’ existence.”). The end, well, it’s a little weak, though if you can buy hard-edged Oklahoma Red’s unlikely transformation, you’ll be okay. Beery’s Red character, who was ready and willing at one point to lead a gang rape of the Girl, comes around when he sees how much each the Arlen and Brooks characters are willing to sacrifice for each other. Once tamed by humanity he leads us into Wellman’s spectacular action packed finale.

But I want you to watch this and probably the best way to sell you on it is to cover the first nine minutes in detail. By the way, “Beggars of Life” can also be viewed in its entirety on YouTube, where it’s found in 10 parts.

Arlen’s Boy tramps his way to a house where he spies a man sitting at the kitchen table with his back to him. Hungry, the Boy knocks, but when there’s no answer he enters. The Boy asks for breakfast, says he’s willing to work for it, but the man still ignores him. The viewer and the Boy must assume the old-timer nodded off at the breakfast table, but as the Boy comes nearer we’re first shown the man’s bloody boot with our view then rising to the man’s face. There’s a bullet hole through his temple. Shocked by the corpse, the Boy knocks something from the table and Wellman cuts immediately to Brooks’ Girl, who dramatically spins to face us from the upper floor, startled by the sound of the breaking glass.

The Boy looks up and sees the Girl staring down at him and the body from the upper level. “Yeah—I did it,” she tells him, explaining that the man had adopted her out of an orphanage two years ago, but he’d “always been after me—pawin’ me with his hands—and this morning—“

Wellman, just 32, but already skillful enough to claim the previous year’s Academy Award winning “Wings” (1927) on his resume, gives Brooks a close-up here—this stood out for me, only having just yet again watched Wellman’s interview in TCM’s “Men Who Made the Movies” series and recalling him stressing that he used the close-up sparingly, only for emphasis. He’d felt they were overused and wanted to make his count. Here he focuses on Brooks’ beautiful face, which displays so perfectly in black and white, and then takes the scene a step further by superimposing the tale of her abuse over that face as she tells her story to Arlen’s Boy. The man tears her dress from her shoulder, he rises from the table and stalks her with outstretched hands, backing her into a wall where the mounted rifle more or less falls into the Girl’s hands, leaving her no choice but to shoot him. He collapses into the chair where the Boy found him and dies.

The Boy hesitates only a moment after hearing this story before asking her “Ever hop a freight train?” He offers to stick the girl on a train heading east, mentioning that he’s heading west himself. The Boy bundles up the food from the dead man’s table and the young man and woman depart, walking off together down the train tracks. Brooks’ girl now outfitted with a cap and baggy clothes which transform her from pretty girl to the Boy’s younger brother, similar to Sally in Wellman’s “Wild Boys of the Road,” or as a possibly more familiar example Veronica Lake’s character in Preston Sturges’ “Sullivan’s Travels.”

The Boy points out a train that passes through St. Paul, apparently perfect for the Girl’s purposes, which include escaping any nasty murder charges, but the Girl’s attempt to board misfires and she winds up toppling into the brush below instead. While the Boy rejoins her steam is seen in the distant background as another train slowly makes its way into the picture heading in the other direction. It’s the Boy’s train. As he prepares to leave her the Girl looks so sad and pathetic that he relents and invites her along. From there our pair are inseparable. It’s their eviction from this train which leads to the sandwich sequence I’d mentioned earlier.

The Boy points out a train that passes through St. Paul, apparently perfect for the Girl’s purposes, which include escaping any nasty murder charges, but the Girl’s attempt to board misfires and she winds up toppling into the brush below instead. While the Boy rejoins her steam is seen in the distant background as another train slowly makes its way into the picture heading in the other direction. It’s the Boy’s train. As he prepares to leave her the Girl looks so sad and pathetic that he relents and invites her along. From there our pair are inseparable. It’s their eviction from this train which leads to the sandwich sequence I’d mentioned earlier.

You should be able to catch all of that action in just Part 1 of the YouTube posting of “Beggars of Life.” From there you’ll likely be hooked, if so, you could do worse than purchase your copy from Grapevine Video. While quite grainy it’s extremely viewable and if you’re like me you prefer to have a copy on your shelf.

Though silent “Beggars of Life” practically speaks to you and may well serve as a good introduction to silent film if you’ve yet to try it. What you’ll see plays like a Wellman pre-Code and once again, despite being made prior to the Stock Market Crash it has as much Great Depression feel as anything put out during the early 30’s. It’s been called Brooks’ best American feature, and it’s an obvious precursor to Wellman’s own “Wild Boys of the Road.” Taking it all together the best way to describe “Beggars of Life” would be ahead of its time.

Leave a Reply