You know, I recorded Lloyd’s of London thinking it was a Tyrone Power film, but when I saw that he was fourth billed and that little Freddie Bartholomew was cast in the lead I was a bit deflated and I let the recording sit for awhile. Now that I’ve watched Lloyd’s I’m loathe to delete it from my DVR … and it is, by the way, a Tryone Power film.

This post isn’t meant to be a history lesson on Lloyd’s as I’m not the one to tell that story and apparently from the bits I’ve read about the film neither really was Twentieth Century-Fox. All the same the film was well-received by Lloyd’s who keeping in character reportedly insured it for $1 million.

No slight intended earlier towards British child star Freddie Bartholomew, I’m a big fan, but seeing him top billed did lead me to believe Lloyd’s of London would be something much different from what I’d expected. Not so. Within a good 20-25 minutes 12-year-old Freddie’s Jonathan Blake grows up to be babyfaced 22-year-old Tyrone Power in what would be a breakout role. This is the first of eleven instances in which Power starred for director Henry King, a winning combination throughout their mutual lifetimes with 1957’s The Sun Also Rises, just a year before Ty’s death at age 44, being their final pairing.

Lloyd’s opens with an entertaining sequence featuring Bartholomew’s younger Blake, a poor kid who waits tables at his Aunt’s ramshackle tavern (Una O’Connor doing her usual fun and frantic routine), getting into mischief with his pal Horatio (Douglas Scott), who comes from much better means and happens to grow up to be Lord Nelson. Jonathan coaxes Horatio out of his lessons and tells him about a couple of pirates who’d just left the pub. He wants to follow them down to their ship but he has to goad Horatio into coming through their usual dare which calls upon loyalty to one another with a punch in the nose the alternative.

On board the ship the boys witness a near mutiny over the split of booty that the captain plans to make disappear in order to double-dip on their claim with Lloyd’s. After narrowly escaping the ship the boys decide they must make the 100 mile trek to London to speak to Mr. Lloyd. When Horatio is invited to serve aboard his Uncle’s ship he has to decline, as this could be the start of a great career, though departs as a gentleman offering up his chin to Jonathan who gives it a loving tap before wishing him well. Young Jonathan Blake heads off to London on his own.

At Lloyd’s we meet John Julius Angerstein, a top syndicate member, played warmly by Sir Guy Standing. We’re treated to late 18th Century action on Lloyd’s floor which mainly consists of responding to a bell rung once for bad news and twice for good. The primary business is insurance of ships, so one gong typically means something has sunk, while two signifies safe passage. Young Blake is fascinated by the action and ingratiates himself with Angerstein through his active curiosity. In exchange for the information he’s brought regarding the pirates back home he turns down any potential monetary reward in favor of a job as a waiter at Lloyd’s.

Power excels in his first scene as Blake subtly yet expertly mimicking Bartholomew’s speech patterns. I was taken aback for a moment thinking he didn’t sound like Ty Power, but then it dawned on me that he did sound like Jonathan Blake. He drifts away from this through most of the remainder of the film, though seems to call upon it when talking with father figure Angerstein which adds a layer to their encounters. Power’s youth is almost startling here considering how he’d age so soon, looking well beyond his years just after World War II and appearing almost elderly just prior to his early passing.

In Lloyd’s of London young Power manages to have his share of adventure, carries several scenes through acting ability alone, and even cultivates his matinee idol image through his romance with Madeleine Carroll’s Lady Elizabeth. Carroll is excellent here though at the same time perhaps overshadowed by very likable Virginia Field as low-bodiced Lloyd’s waitress Polly, who seemed a much more suitable match for Power’s Blake. While Polly does her best to land Blake throughout the film their relationship appears platonic and the kind-hearted girl even manages to conduct herself without the least hint of jealousy towards Carroll’s Lady Elizabeth.

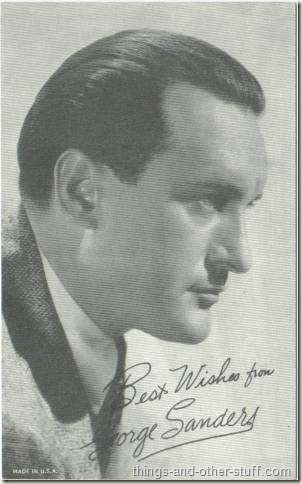

George Sanders delivers his first American performance in Lloyd’s of London and if there’s a black hat beyond the references to Napoleon’s movements it’s Sanders’ Lord Stacy who flaunts his title at every chance, especially in trying to gain entrance to Lloyd’s. Lord Stacy runs up debts, exploits his wife, and generally acts like the cad we’ll come to love in later George Sanders’ pictures.

C. Aubrey Smith is Old "Q," an aide to the Prince of Wales, who despite having a very small role does manage to be part of the funniest scene at a party with Field’s Polly, whom go-getter Blake has insured will meet the Prince that evening. It’s a laugh out loud moment when Old Q makes the introduction. By the way, C. Aubrey’s a bit of a dirty old man here. While I was somewhat stunned to begin with that Field’s low cut outfits passed censors, I really have to assume someone was distracted when the scene passed where Smith wraps her up so tight that you can see Field trying to pry his hands off her chest!

Back to the story, as Blake rises in the industry he does take some gentle rebukes from the kindly Angerstein, who feels his young protege is somewhat degrading Lloyd’s through schemes such as insuring a dancer’s legs and offering other non-traditional coverage. But as the main conflict of the film develops, it’s Blake who takes not only a moral but a patriotic stand. After the Lloyd’s syndicates are nearly wiped out by Napoleon’s rampage against the British shipping industry they, led by Angerstein, prohibitively raise rates against the British shipping industry. The idea being that rather than shutting down industry nationwide such a move would pressure the British government into sending half of Lord Nelson’s fleet off to protect the merchant ships. This outrages Blake who not only takes a stand but scolds mentor Angerstein in the process before risking everything to protect not only his boyhood friend but his nation from Napoleon’s devastation.

Obviously I enjoyed Lloyd’s of London, a tremendous cast, wonderful story, and though I know facts were bent some I’m still sure I learned a little bit about how Lloyd’s worked in the late-18th/early 19th century. My only criticism would be unfounded fears after Blake meets Lady Elizabeth that a film that’d had it’s share of adventure was suddenly morphing into one hundred percent romance, but they pulled back in time, produced a lot of conflict along the way where the remaining love story fit snugly into the tale and enhanced the overall story.

A Twentieth Century-Fox film, I don’t believe Turner Classic Movies airs it very often, if at all, but Lloyd’s of London has run at least twice in the past month or so on Fox Movie Channel, and I expect it receives somewhat regular rotation there. I’m aware Fox Movie Channel isn’t available in all areas, and so if that’s you, I, ahem, suggest you search YouTube at your earliest convenience.

Ran into an excellent Tyrone Power site when I Googled him tonight, especially enjoyed the Articles section which reproduces several pages from original vintage magazines and newspapers. Great Power source!

What is the name of the sad funeral song that is played at Nelson’s procession, when Tyrone Power is satnding at the window.

Brad, I can’t remember well enough to say (wrote this one 5 years ago), but maybe it’s one of those listed on the IMDb soundtrack page?