Diamond Jim Brady

The Preston Sturges’ scripted “Diamond Jim,” starring Edward Arnold as James Buchanan Brady, opens with a message making clear that despite being based on the life of Brady “some rearrangement of facts is obviously necessary.” So before writing about my viewing of “Diamond Jim” for Immortal Ephemera I wanted to seek out some info about the real man and basically see just how much rearranging had been done.

Frankly I didn’t know too much about Brady beforehand other than his obvious penchant for jewels and his famed overeating. Google him–it’s his legendary skills at the table which keep the legend alive today. The search results would have you think he’d been called “Bottomless Pit Brady” rather than “Diamond Jim,” with several of the first few pages on Google from food writers and gourmet sites who take pleasure in cataloging Brady’s daily menu, a list certainly on par with some larger zoo animals, just more variety. Now the movie certainly drew upon his (over)eating, to the point where it becomes clear that food is the one love which never disappointed Brady, but those eating habits appear to have really been spun into legend as time has passed.

However, one article, Whether True or False, a Real Stretch by David Kamp, which appeared in the New York Times (Dining and Wine section, of course) quite recently, December 30, 2008, sought to debunk Brady’s feats of legend at the banquet table.

Kamp quotes John Mariani’s “America Eats Out” for the standard Brady menu, and I’ll do the same–I apologize for the length of the quote, but I can only attribute it to the length of Brady’s supposed daily menu:

Brady is described as having routinely begun his day “with a hefty breakfast of eggs, breads, muffins, grits, pancakes, steaks, chops, fried potatoes, and pitchers of orange juice. He’d stave off mid-morning hunger by downing two or three dozen clams or oysters, then repair to Delmonico’s or Rector’s for a lunch that consisted of more oysters and clams, lobsters, crabs, a joint of beef, pie, and more orange juice.”

In midafternoon, allegedly, came a snack “of more seafood,” followed by dinner: “Three dozen oysters (the largest Lynnhavens were saved for him), a dozen crabs, six or seven lobsters, terrapin soup,” and a steak, with a dessert of “a tray full of pastries… and two pounds of bonbons.” Later in the evening, allegedly, came an après-theater supper of “a few game birds and more orange juice.”

So if you’re wondering why this man’s eating habits have become the stuff of legend, there you go!

But Kamp’s article seeks to track down the origin of this story and perhaps not coincidentally the source he comes upon is the same source which Universal had purchased for Sturges to base his script upon: “Diamond Jim” by Parker Morrell, published in 1933.

Kamp notes that the entire familiar roll call of Brady’s supposed daily diet originates in the Morrell biography, but what he spots about all of this eating is that “they take place at different times; Morell does not conflate them into one single, purportedly typical day in Brady’s life.”

So as common sense would dictate, Brady’s eating has almost assuredly been exaggerated and romanticized over the years.

Edward Arnold at the table in Diamond Jim

I found a much earlier article, that also appeared in the New York Times, far more telling. Brady’s obituary, published April 14, 1917, which runs 1,860 words, only finds it necessary to mention his eating twice in passing (“He liked elaborate meals and the company of pretty women…” and “… he certainly was an eater, being particularly fond of sweets …”) and focuses in much greater detail on his passion for jewels, his career, and his generosity–he donated $200,000 to Johns Hopkins in 1912, a scene which is covered in the movie, “Diamond Jim.”

Brady is remembered as a hard worker between the hours of 9 and 5 who neither drank nor smoked, but loved to dance (not in the movie), with a large collection of jewels that he wore on a daily basis. He had a special fondness for diamonds and apparently rubies as well. The 1917 article states:

Mr. Brady began to gather jewels about twenty-five years ago. …”My pets,” he often called them. He wore a $9,000 watch and in the handle of an umbrella he had set a jewel worth $1,500. His garter clasps, his suspender buckles, and even his underwear were ornamented with jewels.

His collection, it is reported, has been left to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He had twenty-one sets of jewels, scarf pin, ring, shirt studs, and cuff links, and each set represented, it is said, approximately $50,000.

So while his eating has apparently been enhanced over time, it seems that the “Diamond” nickname was entirely appropriate.

Finally, using the 1917 Times article as the source, the following is a quick attempt at Diamond Jim’s real life and times with references to the jewels and the dinner table omitted:

James Buchanan Brady was born August 12, 1856. He was educated in public schools after which he went on to become a messenger boy for the New York Central Railroad. After selling a hacksaw for Charles Moore, Brady became successful as a salesman for machinery manufacturers, Manning, Maxwell & Moore. He then became identified with the Fox Pressed Steel Car Company before going on to have numerous affiliations within the railroad and manufacturing industries, including all of the following at the time of his death:

- Vice-President of Standard Car Company

- President and Director of the Independent Pneumatic Tool Company

- Director of Manning, Maxwell & Moore

- Director of the United Injector Company

- Vice President of the Keith Car and Manufacturing Company

- Vice President of the Osgood-Bradley Car Company

- Director of the Consolidated Safety Valve Company

- Director of the Union Injector Company

He grew his fortune with aggressive investments on Wall Street. In 1912 Brady donated $200,000 to Johns Hopkins to build a urology with with an additional $15,000 given to them annually. Brady died April 13, 1917 leaving behind an estimated fortune of between $10,000,000-$20,000,000.

His friend, Fred Houseman, a broker and member of A.A. Houseman and Company, had this to say of Brady immediately after his death:

“Jim Brady was one of the greatest men this country has produced. Not only as a salesman, but as a real man. There never was an appeal made to him for money or clothes by man or woman to which he did not respond…He never touched liquor, tobacco, tea, or coffee, but he certainly was an eater, being particularly fond of sweets. I have seen him eat a pound of

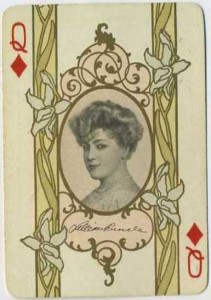

Lillian Russell pictured on a 1908 Playing Card

candy in five minutes…His will undoubtedly will be found to be one of the most remarkable documents of its kind. Johns Hopkins Hospital; will get most of his money. … I never knew him to tell a lie, and I think that was, in part, responsible for his success”

It’s noted that Brady had never married, his relationship with Lillian Russell is not cited, likely out of respect, and the article opens with a statement of how Brady was probably best known at the time of his death, stating he “was famed from Broadway to the Golden Gate as the best-known man in the nightlife of Broadway, an indefatigable first-nighter and a tireless dancer.”

Edward Arnold, Jean Arthur and Cesar Romero in Diamond Jim

[…] born on Aug. 12 were Gilded Era businessman, legendary hungryman and cherished philanthropist James Buchanan “Diamond Jim” Brady (1856-1917); American educator and internationally beloved […]