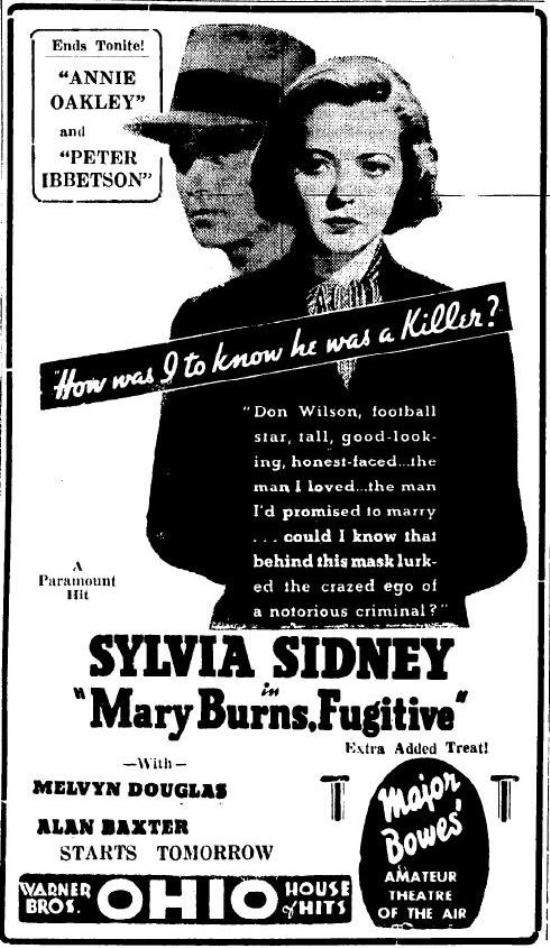

I’ll likely have more on Sylvia Sidney some time soon as I’ve been on a real kick lately having enjoyed her in titles such as Pick-up, Jennie Gerhardt (both 1933), and Good Dame (1934). After those I was pretty excited to watch my most recent arrival, Mary Burns, Fugitive (1935), a fast moving crime story focusing on Sidney as Alan Baxter’s accidental moll.

Sylvia Sidney plays Mary Burns of the title, a good girl who runs a coffee shop a hundred miles outside of the city, in the middle of nowhere. Mary is especially cheery on the evening we check in with her because she’s expecting a visit from her mysterious boyfriend, Babe, whom she hasn’t seen in several weeks.

Babe Wilson is Alan Baxter, an actor who had previously never left much of an impression on me, but is about to in this, his movie debut.

Mary is all dressed up waiting for Babe, who relaxes in the passenger seat as “I’m in the Mood for Love,” a tune introduced just a few months earlier in Paramount’s own Every Night at Eight, plays on the radio.

Mary rushes into Babe’s arms, practically delirious at his arrival. Even Babe’s friend Joe, who got on his case a little about Mary during the drive in, cracks a smile at the young lovers reunited after weeks apart.

Babe quickly springs a surprise on Mary with a pair of honeymoon tickets to Canada. He wants to marry her tonight and take Mary away with him across the border. Mary is stunned. What about her business, the Coffee Cup? Babe tells her to give it to the woman who works for her. The deal he’s been working on has come through and it’s time to go.

Swept up by the excitement, Mary agrees.

All of the light Mary had brought to Babe’s face washes away as Joe frantically whistles from the distance. Babe springs from the grass and races to the Coffee Cup for cover.

Within moments machine guns are rattling from outside. Babe is burning evidence in Mary’s stove while Joe provides cover, firing his weapon until he is hit himself. Joe begs Babe for help, threatening to squeal if he doesn’t get it. Babe’s expression doesn’t change, but a cloud of smoke rises in front of his face. His gun was pointed at Joe. Dead.

Meanwhile Mary is a mess. Begging Babe for an explanation she watches the love of her life take a shot at a cop before diving through a glass window and out of her shop to escape. The lawmen enter Mary Burns’ Coffee Cup, surrounding Mary as she attempts to exit. She looks up in horror realizing that she’s been left holding the bag.

Babe Wilson was not what Mary Burns had expected. Ignorance has cost Mary Burns a 15 year jail sentence.

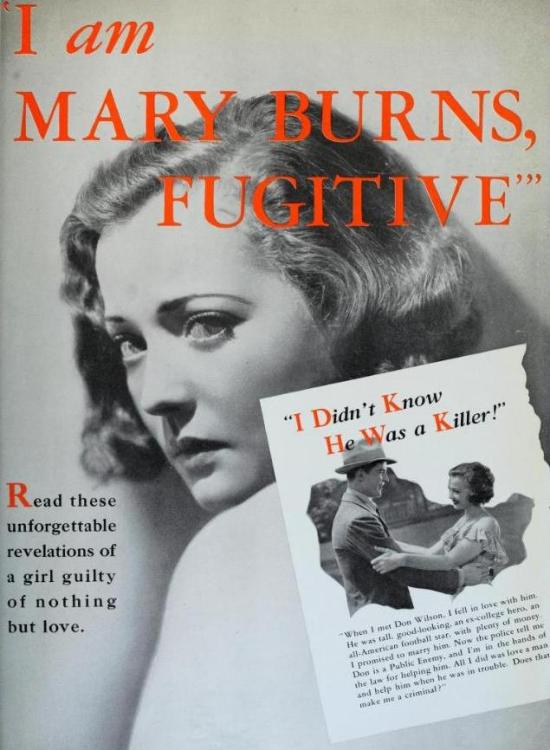

Sylvia Sidney is quite sweet as Mary Burns, but she’s playing what she almost always plays during this period: good woman blindsided by circumstance and perceived to be bad.

She’s wonderful at this, aided by her huge, often sad, eyes and cherubic face, yet always shattering the typically neutral dialects of the other actors with her natural Bronx tones that somehow coat our angel with, if not a hint of experience, at least an extra layer of strength.

Mary Burns, Fugitive is Sylvia Sidney’s first film for Walter Wanger at Paramount after her original contract at the studio had expired. She had first arrived at Paramount in 1931 as Clara Bow’s replacement in the better recalled crime classic City Streets prior to appearing in what was supposed to be her first film for them, an adaptation of Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (1931). Sidney was next loaned out to Goldwyn where she made a hit starring in Street Scene (1931). That was followed by a string of Paramount features starring the same suffering Sidney we see in this first Wanger production.

Mary Burns, Fugitive would have been a bit of a let down for Sidney in 1935. There had been plans for several prestigious literary adaptations with Wanger, but Mary Burns did prove popular with audiences of the day and has, other than the soundtrack, aged extremely well for modern viewers.

In prison Sidney is bunked with tough talking Pert Kelton, but neither stays very long. After a meeting with “Mr. Cameron” (Wallace Ford) of the parole board fails to gain Mary Burns any traction towards release she asks in on a prison break planned by Kelton’s Goldie Gordon.

There’s very little freedom for Mary Burns on the outside as she is constantly looking over her shoulder for Babe as much as she is the law. Things aren’t going very well with Goldie inside the apartment either, as she’s convinced Mary was holding out on cops with information about Babe and now she wants her own piece of that action. But even as she smacks Mary while demanding information, there’s more to Goldie’s situation than it had first appeared.

Wallace Ford has taken a room next door after it is a little too quickly revealed that he’s not Mr. Cameron of the parole board but Harper, a hard-boiled G-man hell bent on bringing Babe Wilson to justice. Up to this point the Wallace Ford I’m used to typically played good-natured fools, often lightening up more serious fare, but his no bones G-man of Mary Burns, Fugitive is more of a sign of things to come for the very active character actor.

Meanwhile we haven’t seen the last of Alan Baxter’s Babe either. He’s hiding out with his gang, highlighted by top henchman Spike, played by an especially menacing Brian Donlevy. Following the light moments in his first scene Baxter is threatening throughout as Babe Wilson.

Baxter very much seemed a prototype of the tight lipped tough guys Alan Ladd would be playing for Paramount in just a few years. Mary Burns, Fugitive makes me want to watch The Glass Key (1942) again to see Ladd with Donlevy as opposed to Donlevy’s performance here alongside Baxter.

Babe remains obsessed with Mary. The problem is that he’s so self-absorbed that he honestly believes Mary still loves him and wants him to find her. Meanwhile Mary is falling in love with the explorer Barton Powell (Melvyn Douglas), whom she meets through her job washing dishes at the Mercy Hospital.

Powell has an eye injury that leaves him blindfolded and extremely cranky. None of the nurses want to serve him anymore and so it falls upon Mary—now calling herself Alice Brown—to bring him his coffee. Well, if there’s one thing our Mary can do it’s brew a fine cup of coffee which, along with that wonderful Sylvia Sidney voice I mentioned, completely soothes the surly explorer.

“You don’t know what a relief it is to hear a woman that doesn’t sound like morning in the barnyard,” says Powell. Melvyn Douglas and Sylvia Sidney have several sweet scenes together in his hospital room, the best of which comes in a cute argument over Popeye and Wimpy as she reads him the comics out of the newspaper.

After a visit from Donlevy’s Spike forces Mary to make yet another escape, she stops at Powell’s hospital room to say goodbye. Powell wants her to come be his secretary after his release from the hospital, but Mary says she can’t. Besides she adds, he doesn’t even know what she looks like. “I don’t care if you’ve got a face like a mud pie,” he replies.

But with Babe and his boys after her Mary has no choice but to leave Powell behind. She’s shown hopping a train at the beginning of a travel montage which ends with newspaper headlines announcing that the law is closing in on Babe. That is because Babe is closing in on Mary.

“It’s been driving me mad to think what you’ve gone through,” Babe tells her and adds, “Without me.” He pauses before climbing from delusional to demented: “You’re mine.”

The final 25-30 minutes of Mary Burns, Fugitive focuses on Harper’s chase of Babe while Babe chases Mary, Harper’s bait. There’s a controversial Church scene involving a house full of parishioners, some explosives and Baxter at his absolute nastiest as Babe. There’s a car chase. More explosives. And the eventual reuniting of Mary with Powell, who can finally see her and is pleased. Babe isn’t quite so pleased at what he finds once he catches up with them.

Alan Baxter makes a wonderful psychopath as Babe Wilson, especially since he began the film seemingly as just another forgettable love smitten male lead. His lines are delivered in what is practically a monosyllabic whisper from behind an icy stare. Upon watching Mary Burns, Fugitive a second time, the most surprising thing about Baxter is how little he is actually in the movie. He makes a big impression when he is.

William K. Howard directed Mary Burns, Fugitive. Howard had risen through the ranks of silent film in the ‘20s and had already completed both The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932) and The Power and the Glory (1933), a pair of films I’m not in love with myself, but which certainly employ original technique, by the time of this one. Mary Burns, Fugitive is different, but more in terms of story than technique.

Mary Burns, Fugitive is a great place for Sylvia Sidney fans to go after City Streets, Street Scene (1931) and Fury (1936). Unlike the others there is no doubt that Miss Sidney is the star with the various male characters all reacting around her and her situation.

Mary Burns, Fugitive is a Sylvia Sidney romance with a gangster movie wrapped around it for good measure.

Sidney and Melvyn Douglas are wonderful to watch together, but what takes this one to the next level are the Alan Baxter and, to a lesser extent, Brian Donlevy criminals who are a few years ahead of their time in terms of how they carry themselves. That goes for Wallace Ford too, who in a typical crime movie of this period would be the hero as G-man Harper, but is usurped as male focal point by Douglas and subsequently even winds up taking a back seat to baddies Baxter and Donlevy!

An interesting movie makes must viewing for fans of Sidney as well as those who love a good gangster flick. Film noir fans will also find a lot to like in Mary Burns, Fugitive, especially those who enjoy those Alan Ladd tough guys.

Mary Burns, Fugitive has never had a video release, but I’ll once more point you to my source, here.

[phpbaysidebar title=”eBay Shopping” keywords=”Sylvia Sidney,Melvyn Douglas,Brian Donlevy” num=”5″ siteid=”1″ category=”45100″ sort=”EndTimeSoonest” minprice=”39″ maxprice=”699″ id=”2″]

Leave a Reply