I just finished reading Edward G. Robinson’s autobiography, All My Yesterdays

I just finished reading Edward G. Robinson’s autobiography, All My Yesterdays, edited and completed by Robinson’s friend Leonard Spigelgass in 1973, the year of Robinson’s death. I won’t talk much about the book as a whole right now, though I may offer a compare and contrast after I finish Little Caesar

, the 2004 Robinson biography by Alan L. Gansberg.

I will say that the Robinson of All My Yesterdays would best be described as both a gentleman and an intellectual. He doesn’t strike me as a very happy man, but then again All My Yesterdays was undertaken very late in Robinson’s life at a time when he was directly facing his own mortality. It’s only natural that there are regrets (family) and anger (politics) throughout.

But collecting appears to have been a bright spot. Robinson’s passion. Oh, he loved acting and reminiscences over many of his favorite films (He was proudest of Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet [1940]) and co-stars, but once the collecting bug had bit him with all it had Robinson freely admits sacrificing potential higher ideals on screen for a fast buck to grow his well-regarded collection of fine art.

Through a keen eye and escalating wages young Robinson graduated from postcards to prints to original paintings by the masters, eventually building an extremely valuable collection that featured work by many legendary Impressionist painters. They hung on his walls, showed up in his films (Illegal [1955], check the DVD Extras if you own it) and were loaned out to the finest galleries. Robinson was forced to sell his original collection as part of his 1957 divorce settlement. At that time Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos paid $3.5 million. The fact the he then reacquired several of the paintings and began building another collection around them attests to the passion Robinson had for collecting.

Though before I use the “C” word too much, which I am about to, I should add that Spigelgass notes in his afterward how Robinson “resolutely refused to use” the word collection regarding his paintings.

Though before I use the “C” word too much, which I am about to, I should add that Spigelgass notes in his afterward how Robinson “resolutely refused to use” the word collection regarding his paintings.

Never fear if you can’t afford a Gauguin or Cezanne like Robinson owned, he began collecting on a scale we can all relate to:

“I remember, as if it were only yesterday, the delight I felt as I spread out upon the floor of my bedroom the Edward G. Robinson collection of rare cigar bands…I progressed to cigarette pictures of big-league ballplayers…then those never-forgotten cards depicting the great and beautiful ladies of the stage” (Time).

Born in Romania in 1893 and arriving in America in 1903, us cardboard enthusiasts should now pause to wipe the drool away and clear daydreams of time machines from our minds.

He repeats his line about the “Edward G. Robinson collection of rare cigar bands” in a 1953 statement released by The Museum of Modern Art in promotion of his having loaned the museum 40 paintings for display. But it’s Robinson’s opening line of that statement which the universal collector can best relate to:

“I am not a collector. I’m just an innocent bystander who has been taken over by a collection.”

Regarding his collection of rare cigar bands, Robinson continues to speak of general collecting in the opening paragraph of his MOMA statement adding “I didn’t play at it. A collector doesn’t; it’s hard work; it’s an obsession.”

But then, corroborating Spigelgass’ later mention, Robinson then purposely veers away from the idea of being a collector himself at this point in his life: “I left this field of gentle fanaticism to those self-denying people who make it their life work – the collectors. I am just a lover of paintings. I do what I do for the sheer joy of it.”

I’m sorry, Mr. Robinson, but that sounds like a collector of the most exalted order to me.

Robinson describes the moment where he was at last able to understand the role of collector and thus realize what he was attempting to do. It was sometime in late 1936-early 1937 if I’ve correctly understood the sometimes confusing chronology of Robinson’s story. He was in London awaiting a rewrite of Thunder in the City (1937) when he went on a buying spree which eventually took him to a French gallery displaying the collection of Oscar Schmitz. In a page and a half of small-faced type Robinson reproduces his own translation of the catalog describing Schmitz as collector and his collection.

Robinson describes the moment where he was at last able to understand the role of collector and thus realize what he was attempting to do. It was sometime in late 1936-early 1937 if I’ve correctly understood the sometimes confusing chronology of Robinson’s story. He was in London awaiting a rewrite of Thunder in the City (1937) when he went on a buying spree which eventually took him to a French gallery displaying the collection of Oscar Schmitz. In a page and a half of small-faced type Robinson reproduces his own translation of the catalog describing Schmitz as collector and his collection.

A light turns on for him afterwards:

“I immediately felt, as I read this, though I dared not utter it aloud nor even permit myself to give it more than an instant’s thought, that the role of collector had been given a definition I’d been striving to find all my life. A man who is not an artist yet is impelled to support, encourage, and, in effect, subsidize the artist–to make his work available to the public eye–what is he? An egotist? An investor? An exhibitionist getting his kicks by displaying not himself but his ownership? No, said the catalog, a man who ‘can influence the artistic climate of a milieu, of a city, of a country'” (175).

Robinson wonders if that was what he was after and admits that he has no answer. Yet he does conclude this lengthy section upon his collecting activity by stating that the pictures he purchased during that spree “became the nucleus of–forgive me for saying so–one of the greatest collections of French Impressionist art ever assembled by an American” (175).

I mentioned earlier that Robinson spends much of All My Yesterdays reflecting upon regrets both inflicted and imposed. As life seemed to pile up on him collecting was an escape. “I was now not living; I was in the midst of a series of obsessions,” (216) he wrote. He then listed those obsessions: Warner’s belaboring him with work; trying hard to get along with his wife, Gladys; trying to make the world a better place for his son; wondering if the remodeling on his house would ever be complete, and finally: “My pictures: I bought more. I was hooked on art–an addict. The only thing real in the world seemed to be catalogs from dealers, galleries, and museums” (216).

I can understand if a non-collector reads that last paragraph and decides it’s an unhealthy escape. Especially since I’ve already described Robinson as not the cheeriest subject I’ve ever read about. In trying to explain collecting to the non-collector I would offer to think of the collected item(s) as you would the most delicious chocolate bar you’ve ever had. I mean, you take a bite and you gasp. It’s unreal, delicious, so much better than any other that it ought to be illegal. Now think of that chocolate bar and realize that you get to keep it, savor it, forever.

I can understand if a non-collector reads that last paragraph and decides it’s an unhealthy escape. Especially since I’ve already described Robinson as not the cheeriest subject I’ve ever read about. In trying to explain collecting to the non-collector I would offer to think of the collected item(s) as you would the most delicious chocolate bar you’ve ever had. I mean, you take a bite and you gasp. It’s unreal, delicious, so much better than any other that it ought to be illegal. Now think of that chocolate bar and realize that you get to keep it, savor it, forever.

And if you don’t care for chocolate just adjust your taste buds and fill in the blank instead.

In that spirit, I found some of Robinson’s bits of advice to collectors especially keen. He’s talking specifically fine art but much of what he writes is easily transferable to collectors of any bent:

“What you get a feeling about is the subject matter and the skill with which the artist communicates it to you. What you are sensing is within you, not him. You must know what is in him to know if he speaks his own truth–not your truth, but his. I never have been able to” (170). Translation: Respect the object on its own merits.

“If you like it and it does something to you, ignore what I say and acquire it” (170).

“Go to responsible dealers. But do not trust them when they tell you that the painter is in demand for his rarity. The demand for a painter is for his gifts; that his work happens to be rare is important only if you’re a hoarder and if you’re buying as an investment” (171).

“If you’re buying for beauty and to have something to come home to–besides a loving wife and family–don’t buy legends; Buy what you see in front of you” (171).

“If you’re buying for beauty and to have something to come home to–besides a loving wife and family–don’t buy legends; Buy what you see in front of you” (171).

“Some people consider me sharp. Not true. I was never sharp. But I was always aware of the true market value of what I wanted and even more wary of schemes to build up certain painters into fad or fashion. I got stuck once or twice, but I try to avoid it; I will not be a party to the creation of a false reputation” (171-172).

The final lesson from Edward G. Robinson on collecting are the rewards of that keen eye. Like Robinson I have a hard time relating to collecting as an investment. As a dealer I discourage it. This is because I am familiar with the often undefinable act of collecting as passion. But let’s talk dollars and cents anyway.

As I mentioned Robinson’s first collection, of which he was so proud, was sold for $3.5 million in 1957. Beginning with a base of only 14 of his original 74 paintings Robinson would possess a collection eventually totaling 88 masterworks which were sold upon his death for $5.125 million to Victor and Armand Hammer of Knoedler and Company (285). While I’m not going to attempt to adjust for inflation Robinson’s payouts of $3.5 million in 1957 compared to $5.125 in 1973 I will draw the conclusion that he once again built a rather valuable and impressive collection.

Follow your eye, your gut, whatever you’d like to call it. Value follows.

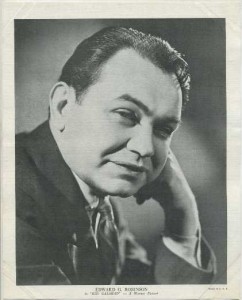

Mr. and Mrs. Edward G. Robinson (Gladys Lloyd) attend a Hollywood premiere together on this undated A.P. Press Photo

Sources:

- “Art. Collectors at Work.” Time Magazine 5 February 1951.

- Robinson, Edward G. and Leonard Spigelgass. All My Yesterdays: An Autobiography

. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc. 1973.

- The Museum of Modern Art. (1953). Paintings from Well-Known Edward G. Robinson Collection to Go on View at Museum [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.moma.org/docs/press_archives/1685/releases/MOMA_1953_0015_15.pdf?2010

Of Interest:

- ICONS Radio Hour – Scroll down alphabetical list on iconsradio player to find “Francesca Robinson on Edward G. Robinson.” John Mulholland intereviews Francesca Robinson about her grandfather’s life and career.

[phpbay]edward g robinson, 12, “45100”, “”, “”, “”, 39[/phpbay]

Thanks for a fascinating post! I read Robinson’s book not long after it came out, thanks to my dad acquiring it, but that was quite a long time ago (grin) so your post provided me witha fresh perspective on it. This focus on Robinson the collector is terrific and something many of us can relate to, on a less expensive scale!

Best wishes,

Laura

Thanks, @6c46afbc58a703991f6026e90f2c0107:disqus while Robinson’s collecting isn’t the major focus of All My Yesterdays, it certainly was a major focus in his life. Reading the book I couldn’t help notice phrases he’d use that I’ve used myself, yes, on a much less expensive scale!