When I told you about the new Criterion release of Island of Lost Souls the other night I mentioned that I was going to go find Lota, the Panther Woman in my next post.

When I told you about the new Criterion release of Island of Lost Souls the other night I mentioned that I was going to go find Lota, the Panther Woman in my next post.

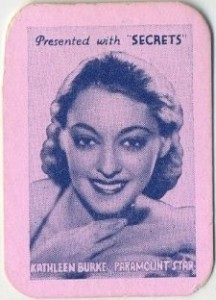

Thanks to the NewspaperArchive.com I succeeded in finding out much of what I wanted to know about unknown Kathleen Burke being cast alongside Charles Laughton, Bela Lugosi and Richard Arlen in Paramount’s adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau. Now I’d love to learn even more!

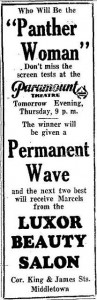

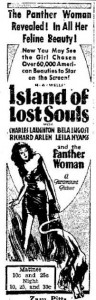

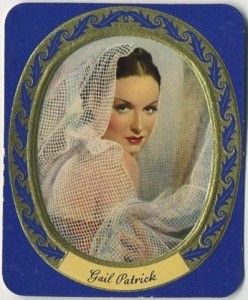

The bare-bone basics on Paramount’s casting of Burke is as follows: In the Summer of 1932 they ran a nationwide contest through Paramount Publix Theatres and affiliated local newspapers calling upon applicants to compete for the part of Lota, the Panther Woman in their forthcoming release, Island of Lost Souls. 60,000 women entered, Kathleen Burke won out in a competition which saw better remembered actresses Gail Patrick and Lona Andre place and show.

I was mostly curious about the timing, the methods and just how deep the publicity ran for the Panther Woman contest. Scanning hundreds of small town local news articles I got a pretty good idea of each!

A tongue-in-cheek article inside the Independent of Helena, Montana reminds us of the times: “While everybody else has been stewing around, wondering where business went and how the election will go and things like that, a movie studio has been conducting a nationwide search for a ‘panther woman.'”

A United Press article that I spotted in Louisiana’s Ruston Daily Leader warned “unsuspecting citizens in New York and all points east and west. Be prepared to combat an epidemic of “Panther Women” during the hot months. Hollywood must be served!”

But if the resulting nationwide coverage is to be believed, then the search for the Panther Woman provided a pleasant little escape for a few months in the Summer of 1932 during low times in the Great Depression.

But if the resulting nationwide coverage is to be believed, then the search for the Panther Woman provided a pleasant little escape for a few months in the Summer of 1932 during low times in the Great Depression.

Arthur L. Mayer, Director of Advertising, Publicity and Exploitation for Paramount Publix Corporation credited the Search for Panther Woman as Paramount’s top exploitation campaign of 1932 in The Film Daily’s 1933 Yearbook of Motion Pictures. Mayer shared the business side of the search in the Film Daily Yearbook:

“The Paramount studio and the leading Publix theater in each city cooperated in the hunt for a girl best suited to the part, and the winner was awarded a motion picture contract plus traveling expenses and hotel accommodations during the filming of the picture.

“Each theater tied up a newspaper to publicize the hunt, and through the tie-up, thousands of inches of valuable publicity were given the picture. Screen tests were made of the entrants locally.

“The increased attendance during the showing of the tests more than paid their cost, leaving each theater an immediate net profit in addition to the accumulated advertising for the picture to be shown at a later date” (675).

There’s an entry blank shown on this page, and I ran into a handful of similar forms from newspapers throughout the country during my search. Another form, not shown here because the print turned out too blurry, set forth the entire 11 point list of “Rules for Contestants.” Qualifications included:

- Must be not under 17 nor over 30 years of age

- Must be in good health

- No less than 5’4″ and no more than 5’8″

- Must have “written endorsement of two citizens of good standing in the community endorsing her morality” (My favorite!)

- Cannot have any screen credit in a nationally distributed motion picture nor a cast credit in any professional stage production; etc.

The winner would be awarded a $200 per week contract with Paramount for a period of 5 weeks and the possibility of the contract being extended if the winner makes good as an actress.

Kathleen Burke, the eventual winner of the Panther Woman role in Island of Lost Souls, would, I gather, make good to some degree, also being cast in Murders in the Zoo (1933) and the Western Sunset Pass (1933) before being released by Paramount after being under contract with them for one year. More on her brief movie career in a bit.

Kathleen Burke, the eventual winner of the Panther Woman role in Island of Lost Souls, would, I gather, make good to some degree, also being cast in Murders in the Zoo (1933) and the Western Sunset Pass (1933) before being released by Paramount after being under contract with them for one year. More on her brief movie career in a bit.

The entry forms were published in July and by August of ’32 papers would be trumpeting their local winners: “Ada Selliers Is ‘Panther Woman'” announced the Alton Telegraph in Illionois; “Miss Jean Bauer Is Named Hamilton’s ‘Panther Woman'” came word from the Hamilton Daily News in Ohio.

The Lowell Sun of Lowell, Massachusetts gave a detailed account of what their local girl made-almost-good went through in capturing regional contests. Miss Dolores Dias of Lincoln Street won the local Lowell competition and from there was sent to the Paramount Theatre in Boston where she managed to survive the competition of 75 Boston area women. From Boston it was off to the New England finals at the Metropolitan Theatre a week later where Miss Dias competed against survivors from Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont, Connecticut, and Maine. Screen and voice tests were made and some of the best, including that of Miss Dias, were forwarded to Hollywood to be put under consideration for the final choice of Panther Woman.

An early article, published in July by the Middletown Times Herald in New York mentioned that the finalists would be judged by a committee said to include Ernst Lubitsch, Cecil B. DeMille, Rouben Mamoulian, and Norman Taurog.

An early article, published in July by the Middletown Times Herald in New York mentioned that the finalists would be judged by a committee said to include Ernst Lubitsch, Cecil B. DeMille, Rouben Mamoulian, and Norman Taurog.

From the 60,000 women 8 finalists were chosen. Actually coverage gets a little choppy here, it appears originally 5 women were chosen and then 3 additional were called upon later. Kathleen Burke, Gail Patrick, Lona Andre and eventual fourth place finisher Verna Hillie, were among the original five and each of them made the final four, each also landing screen work with Paramount when all was said and done.

The September 13 Daily News of Twin Falls, Idaho reported that there was a growing bundle of mail addressed to the Panther Woman awaiting the winner.

Nearly the final stretch when the September 19 Tribune-Republican of Greeley, Colorado carried the article “Voice Tests Given for Panther Woman.” The judges, and I guess that implies those heavy hitter directors I mentioned earlier, were shown blank video which only projected the girl’s voices. Names weren’t used, each prospective Panther Woman was referred to by number.

The first mention I found of Kathleen Burke being declared the winner came in The Lowell Sun on October 5. The same article celebrates the strong showing of the aforementioned Dolores Dias. The winner, Burke, was described as “an alluring brunette, with large and extremely expressive eyes.” They sure put the focus in the right place with those eyes!

The first mention I found of Kathleen Burke being declared the winner came in The Lowell Sun on October 5. The same article celebrates the strong showing of the aforementioned Dolores Dias. The winner, Burke, was described as “an alluring brunette, with large and extremely expressive eyes.” They sure put the focus in the right place with those eyes!

And so Island of Lost Souls went into production, but not without incident for Miss Burke. Engaged at the time to Glen Rardin, who supposedly had entered Burke into the original contest without her knowledge, the rookie actress would flub her lines whenever her fiancé was on the set. Which seems to have been often.

The Syracuse Herald reported on November 3 that when Burke was asked to keep Rardin off the set “She refused. Banning followed.” Gregory Mank, in his commentary on Criterion’s new release of Island of Lost Souls dishes the dirt a little further when he says that Rardin actually got into a fistfight with the director leading to his ban!

But the film was completed and all was well for Kathleen Burke as June 1933 articles reported upon her seeing several of America’s biggest cities in a personal-appearance tour tied to the movie.

But in the aftermath it was discovered that the Panther Woman title did more harm than good.

In a 1935 article by Emily Bowers in the “Screen & Radio Weekly” supplement of the Oakland Tribune Gail Patrick was doing her best to distance herself from her runner-up status referring to Panther Woman as a “ghost of my dark film past.” The writer sympathizes with Patrick noting that “this tale has continued to dog the young actress’ footsteps for two years.”

The same publication, just four months later, carried a feature on Kathleen Burke titled “Ex-Panther Woman: Kathleen Burke Escapes Her Pigeonhole and (Starting with ‘Bengal Lancer’) Begins a Career as an Actress.” The article by Gelal Talata, who claims to be a friend of Kathie’s touts her role in the Gary Cooper feature The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935), in which she admits Burke’s role is little more than a bit. But it’s a beginning towards killing her Panther Woman reputation, which is Burke’s goal.

Burke, who had eventually married and divorced her feisty boyfriend from the time of Island of Lost Souls, married again and appeared in her last film with a small part in 1938’s Rascals at Twentieth Century-Fox. That summer the Associated Press gave her a new headline announcing “Panther Woman Of Screen Is Mother.” Talk about not being able to shake a type!

Burke, who had eventually married and divorced her feisty boyfriend from the time of Island of Lost Souls, married again and appeared in her last film with a small part in 1938’s Rascals at Twentieth Century-Fox. That summer the Associated Press gave her a new headline announcing “Panther Woman Of Screen Is Mother.” Talk about not being able to shake a type!

Burke continued to act, returning to the stage on Long Island where she tried to make the best of her disappointing Hollywood career. She claimed the stage had always been her love having appeared in several High School and amateur productions back in Chicago prior to her entering the Panther Woman contest. She was said to have made a hit on Great Neck, Long Island in a 1942 production of Night Must Fall, and was gearing up to appear in Yes, My Darling Daughter at the same theater.

Burke continued to act, returning to the stage on Long Island where she tried to make the best of her disappointing Hollywood career. She claimed the stage had always been her love having appeared in several High School and amateur productions back in Chicago prior to her entering the Panther Woman contest. She was said to have made a hit on Great Neck, Long Island in a 1942 production of Night Must Fall, and was gearing up to appear in Yes, My Darling Daughter at the same theater.

Just a few years later a brief article about Gail Patrick mentioned the search for Panther Woman, sadly stating that “I can’t at the moment remember her name, but at any rate, a girl was chosen. She didn’t make the grade.”

After 1942 I ran into a gap concerning the life and career of Kathleen Burke which stretched to 1965 when she was found living in Chicago with her third husband, Forrest Smith. Burke’s 1980 obituary in the Chicago Tribune lists her under her married name of Mrs. Forrest Smith, but spends most of its text talking about her brief Hollywood career.

She died of undisclosed causes April 9, 1980 in Chicago, survived by her mother, husband, and daughter from a previous marriage. Kathleen Burke Smith was 66.

Even after the contest, once the film was released, the focus seemed to stay on the Panther Woman ballyhoo

Sources:

Lots of little newspapers to thank for this one. Again, most of these articles can be found inside NewspaperArchive.com. If you use my link to subscribe I get a small affiliate commission, you get my great thanks and access to a heck of a database!

- Bowers, Emily. “An Alabama Star Falls on Hollywood.” Oakland Tribune. 24 February 1935: 52.

- “Hollywood Film Shop.” Ruston Daily Leader. 25 July 1932: 8.

- “Kathleen Burke Now Seeks Freedom From Panther Woman.” Del Rio News-Herald. 18 July 1942: 3.

- “Man About Town.” The Lowell Sun. 5 October 1932: 58.

- Mayer, Arthur L. “Search for Panther Woman Was Paramount’s Best.” The 1933 Film Daily Year Book. Ed. Jack Alicoate. 1933.

- “Mrs. Forrest Smith.” Obituary. Chicago Tribune. 11 April 1980.

- “Panther Woman Gets Guest Day at Roxy; Big Bunch of Letters.” Twin Falls Daily News. 13 September 1932: 3.

- “Panther Woman’s Fiance Barred From Her Studio.” Syracuse Herald. 3 November 1932: 30.

- “Search for Panther Woman.” Winnipeg Free Press. 10 June 1946.

- Talata, Gelal. “Ex-Panther Woman.” Oakland Tribune. 23 June 1935: 70.

- “The Gals Go Pantherish.” Helena Independent. 9 October 1932: 14.

- “Voice Tests Given for Panther Woman.” The Tribune-Republican. 19 September 1932: 5.

- “Woman Sought for Role of Panther Girl.” Middletown Times Herald. 20 July 1932: 2.

Supposedly Gail Patrick once said that the best thing that ever happened in her career was NOT getting the part of the Panther Woman, noting how the role always dogged Kathleen Burke (though they appeared together in the Lionel Atwill film ‘Murders in the Zoo,’ in which Kathleen looks far more stylish than she did on Laughton’s island). Burke seems to have had genuine talent; a pity her career didn’t take off. Thanks for such a fascinating and informative post!

Thanks for reading! Yes, that one 1935 Screen & Radio Weekly article began clearing the air over Patrick’s embarrassment over two dark ghosts of her screen past: the whole Panther Woman thing along with her hopes of one day going into politics, which she said was just something she said more or less to sound interesting when she first got to Hollywood.

Regarding Burke, it was interesting that the deeper she got into her career the more early experience she seemed to recall having had in Chicago prior to winning the contest. By the 1942 article I mention and another I spotted from about the same time it sounds like she always wanted to act, while back in ’32 she insisted she only entered the contest because her boyfriend sent off the info without her knowledge.