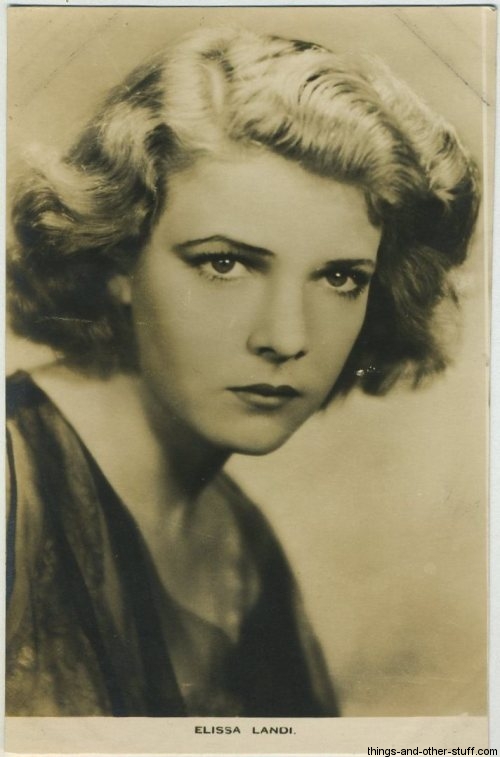

Elissa Landi, born Elizabeth Marie Christine Kühnelt in Venice, Italy, December 6, 1904, had a life and background as colorful as those personal statistics would lead you to believe. Plucked by Hollywood from Broadway after just a single role, playing Catherine Barkley in the short-lived but well-publicized 1930 production of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, Elissa Landi chose Fox over several other companies. She began her service on a three year contract with the lead opposite Charles Farrell in 1931’s Body and Soul, a film which also featured up and comers Humphrey Bogart and Myrna Loy. Body and Soul was panned but in it’s review TIME Magazine went so far as to call it noteworthy because of Landi’s appearance, extolled the actress’s beauty and talents, and even referred to her as Fox’s Garbo.

This began the period of her career which Landi is best remembered for, though by the release of Body of Soul she had already appeared in more than a half dozen films in Britain, published two novels, and made many a stop between Venice and Hollywood!

The name isn’t pulled as far out of nowhere as you might think. Elissa is obviously a play on Elizabeth, Landi is the name of her mother’s second husband, the Count Zanardi Landi. While the Count surely had a colorful background, including taking on a three-year contract beginning 1922 to attempt to raise the Lusitania in hopes of resurrecting treasure from the sea floor, he pales in comparison to Elissa’s mother, the Countess Caroline Landi.

The Countess claimed, in book form, to be the youngest child of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria kept secret from the public by her mother, the Empress Elizabeth, in order to preserve her from “the useless and dangerous life of courts, because I did not wish you to be an empty-headed, empty-hearted princess” (The Secret of an Empress). The assassination of the Empress in 1898 either snuffed out any chance of Caroline being publicly claimed as royalty or conveniently closed the timeline on her carefully concocted story which in its published form was actually referred to by the Boston Daily Globe as “a most interesting narrative, attaining both consistency and plausibility, while offering a wonderful wealth of detail.” In 1913 the Countess claimed to have turned down a royal offer of $400,000 to keep silent saying that she didn’t want the money but to be recognized as legitimate.

One can imagine the wealth of stories covering the emergence of Hollywood’s new royal Princess upon Elissa Landi’s initial rise to fame. Whether careful publicity or true annoyance Landi took issue with the claims in 1932, preferring to be recognized for her own efforts on the screen: “I wish the story had never been told. I reached my present position without the aid of it and I do not think it will help me one whit in the future. I want to be judged as any other worker–solely on the merit of my job.”

Further eroding the potential legitimacy of the story was Landi’s reaction when asked to prove the claim, which the article points out were published “without her knowledge or consent.” Landi said, “Publication now is more of a danger than an aid. Insofar as it has any effect at all, it introduces an utterly alien element in people’s consideration of me. I want to be judged as an actress and a writer. My work is open to examination and criticism by everyone. Not only must it stand by itself, I want it to.” As Landi’s career advanced that appears to be exactly what happened as mention of the Countess’ parentage is largely dropped from mention, though I must admit I chuckled when the famed Louella Parsons referred to Landi’s mother as “Caroline, countess of something or other,” in a 1933 article.

But there I go prematurely transporting Elissa Landi to Hollywood again, doing so without even mentioning her father, Richard Kühnelt. Another book purporting Caroline as the Emperor and Empress’ daughter, My Years at the Austrian Court, by Nellie Ryan, was published in 1915, and while I’m very skeptical about the royal ties the book does give a detailed account of Caroline’s wanderings with specifics that match the generalities reported in later Elissa Landi biographical sketches. In fact, Ryan’s book, available for reading in its entirety on Google, even includes the photo of Elissa Landi and her brother that is shown here:

As to their travels, Caroline’s guardian had died and she found herself arranged into a marriage with Kühnelt in January 1902. Ryan writes that “there was no real love between these two” and that “the marriage was not happy.” Elissa’s older brother, Anthony Francis, was born in 1902, she in 1904. Kühnelt wound up making a series of bad investments which eventually landed the family in Vienna “where they lived for awhile in absolute poverty.” Matters worsened as Kühnelt stopped working and the family left Europe altogether settling in Montreal, Canada in 1906 where according to Ryan, “Kühnelt seems to have treated his wife and children in a most brutal manner.” They separated in 1908 with Kühnelt departing to New York while Caroline took the children to British Columbia.

Caroline became a cook and soon after appears to have opened a business of her own selling sweets. She met Count Zanardi Landi in Vancouver and after spending about a year in securing her divorce from Kühnelt she became the Countess Landi. A 1939 article in the Hagerstown Daily Mail quotes Elissa as saying, “My first actual memories are of an old red-brown house in Vancouver, B.C., where tramcars passed by and a hardy mountain ash flourished outside the door.” The same article mentions time spent by the Landi family in Turkey before settling in London, where during the First World War Elissa became a dance student of Madame Serafine Astaflava of the Imperial Russian ballet. Sure enough, nearly 25 years earlier Nellie Ryan wrote of “little Marie Christine” that “she is most clever and amusing, dances exquisitely and is already writing wonderful stories. She has some lessons with a Russian lady, others with a French lady, and music is taught by a good professor.”

It was in London that Elissa Landi had hopes of writing for the stage but soon found herself a member of a small repertory company at Oxford instead. From there she was chosen to appear in Storm, which in turn lead to those early British films as well as one in Sweden opposite Lars Hanson. She came to America for A Farewell to Arms, and while the production was short-lived, Landi appears to have stolen the show, being called out by Time Magazine, along with co-star Glenn Anders as “ideally suited to the parts they play;” Charles Darnton of the New York Evening World said Landi “achieved a beautiful, courageous and truly moving performance;” Robert Coleman of the Daily Mirror wrote that she “made a most auspicious debut. She has beauty, poise, and polish;” and Baird Leonard of the old Life Magazine wrote “When it comes to Elissa Landi, words fail me. She is the loveliest creature you will see in many a season” (Kerrville Times). After A Farewell to Arms Landi wouldn’t return to the stage until the last few days of 1935–as mentioned earlier, the performance was impressive enough to immediately garner her a Hollywood contract.

Starting with 1931’s Body and Soul Elissa Landi would appear in 19 U.S. films through 1935, often as the female lead as she attained immediate star status. Of 1932’s The Devil’s Lottery TIME Magazine wrote “Simultaneously last week were released Elissa Landi’s third novel and her fifth cinema. She had reason to be pleased with both.” The book, by the way, was titled House for Sale and published by Doubleday Doran. TIME wasn’t as kind with Landi’s next release, The Woman in Room 13, where “Miss Landi’s latest cinema venture makes you think her time on location would have been spent to better advantage had she used it to start another novel.” TIME continued to sympathize with Landi as it felt Fox was wasting her talents in her next picture as well, A Passport to Hell, where “Miss Landi tries hard to act dramatically but is unable to do much more than stride up & down with an anxious stoop, clasping her face and muttering: ‘It can’t go on like this.'”

Landi’s next film found her loaned to Cecil B. De Mille at Paramount for his classic The Sign of the Cross (1932) which placed her alongside Fredric March and billed over Claudette Colbert and Charles Laughton. Being a DeMille epic, The Sign of the Cross was perhaps too large for TIME to single out Landi, but they did quote De Mille on why she was cast: “. . . She combines mysticism and sex with the pure and wholesome. There is the depth of the ages in her eyes, today in her body and tomorrow in her spirit.”

Reviews typically noted Landi’s beauty and the fact that she was cast against her usual type, which better suited Claudette Colbert’s Poppea role at that time. The Hagerstown, Maryland’s Daily Mail offered high praise of the film as a whole and especially Landi writing “It is her greatest role and one of the finest performances that has been on the screen.” The film moves slow today and is seemingly best remembered for its other assets including Colbert’s provocative milk bath, Laughton’s over the top Nero, or the sensational games Nero put on with warriors and wild animals, but it was greeted with high praise in 1932 because it harkened back to the earlier silent epics and the screen had not seen anything like it in a few years. The overall virtue of Landi’s Mercia character likely helped it in the press as well, especially with the picture’s Christmastime release.

Landi’s next film went back even further than The Sign of the Cross. The Warrior’s Husband (1933) was a comedy of Ancient Greece based upon a recent stage hit of the same name which had starred Katharine Hepburn in the role of Antiope, played by Landi on screen. It sounds interesting and hard to find (someone on the IMDb remarked that it can be viewed at the Museum of Modern Art). After her following film, I Loved You Wednesday (1933), Landi severed her contract with Fox and freelanced. An interesting note by Louella Parsons, which correctly states Landi was to appear opposite Francis Lederer in Man of Two Worlds (1934), also states that she will co-star with Clark Gable in Frank Capra’s Night Bus (Parsons 1933-10-26). Night Bus evolved into the multiple Academy Award winner It Happened One Night and thankfully Claudette Colbert played the part Louella had Landi marked down for.

Despite the high praise of the period I find Landi’s main virtue continues to be her beauty while her acting style remains competent but unremarkable. I really couldn’t imagine her taking on Gable in It Happened One Night. After her Mercia in Sign of the Cross I’d imagine that the Walls of Jericho would need to be made of steel!

The 1934 classic Landi did appear in in, The Count of Monte Cristo, where she played Mercedes opposite Robert Donat, was a much smaller but much more fitting part for the staid beauty. By the time of The Count of Monte Cristo the reviews had stopped revolving around Landi and she garnered only brief, but admirable, mention in Andre Sennwald’s New York Times review of the hit picture: “The heroine in ‘Monte Cristo’ is pretty small fry, but Elissa Landi gives her a handsome and gallant look.”

Following the Count, the next set of headlines to greet Elissa Landi were unfortunately off-screen news as she made more front pages than you would have imagined for her divorce proceedings. While obituaries noted that Landi, often called “the loneliest woman in Hollywood,” kept so much to herself that no one even realized she was married until the divorce cropped up, her marriage to John Cecil Lawrence was mentioned in articles as early as those heralding her 1931 arrival in Hollywood, so surely there was no great mystery. The reason confusion likely cropped up was because Lawrence had moved back to Britain after just one month in America with Landi, while she continued to star from Hollywood and only visited home on a few occasions, notably to gather her parents and settle them in Hollywood.

After a legal separation and following a final three years of marriage which Landi referred to as “a farce,” she officially filed for divorce in Los Angeles sometime in 1934. Landi, backed up by her mother, charged that Lawrence had suggested an open marriage, though the official charge was mental cruelty. Lawrence, a London barrister himself, ignored the L.A.’s courts granting of the divorce claiming they had no jurisdiction over their marriage. He filed himself from London claiming infidelity on Landi’s part. In May 1936 the final decree went through leaving Landi free to marry again, something she had no plans to do at the time.

She was a solitary woman, likely only lonely from the perspective of others as she appears to have been quite happy living in her Hollywood home with her mother and father and spending her spare time writing. She was quoted as saying “I adore solitude. I mean, when I am alone puttering around my garden, I am alone only as far as human beings are concerned. My pets, six dogs and five cats, are at my heals” (Landi Denies). The same article mentions her love of Hollywood and she states, “I will not sacrifice my work and health for social engagements,” to explain why she kept to herself.

Besides her novels, poetry and play writing, Landi kept herself busy with a small printing press she had acquired and dreamed of publishing a little newsletter of some sort–I can only imagine she’d be a prolific blogger in this day and age! At the time of her divorce Landi rhapsodized about her love of her adopted country and planned to attain her American citizenship as soon as possible, something she did in 1937.

After a contract with Paramount expired Landi was seen in the second of MGM’s Thin Man movies, After the Thin Man starring William Powell and Myrna Loy (the one with Jimmy Stewart). She then headed East and while her time in New York appears very busy I can’t nail down why she left Hollywood after completing her third consecutive film for MGM, 1937’s The Thirteenth Chair. Well, I have a good guess: Landi was no longer the star of her Hollywood productions, but she could be the lead on Broadway where she starred in three consecutive flops. During this time in New York her name appeared in Walter Winchell’s column linking her to opera tenor Nino Martini a few times in 1938, but nothing came of that. Landi was also said to be busy in her Manhattan apartment working on her fifth book.

Whatever the case may be Elissa Landi apparently enjoyed the East Coast as she purchased a stone dwelling in Kingston, New York in 1939 which she moved her father, the Count Zanardi Landi, into. Her mother, the Countess Caroline Zanardi Landi had died in late 1935. Landi seems to have busied herself with her writing and a number of lecture tours throughout the 1940’s, pausing to make her Hollywood comeback in the 1943 PRC war film Corregidor, a cheapie you can view for free on the Internet Archive. The story finds Landi in a love triangle amidst the bombing of the Philippines.

Landi stood by the film, inflating its importance some in an interview with the Ogden Standard-Examiner of Utah: “Here was an opportunity to depict the part one woman played in the hell of that defense of the Philippines … and to bring home to others, as it had to me, the difficulties and hardships which countless unsung heroines are facing in a job which belongs to us all.” Landi continues to celebrate the contribution of women to the war effort saying, “they are doing their bit by joining the WAVES, WACCS, the SPARS or marines and many are taking men’s places in business, munition plants and defense jobs.”

The Standard-Examiner article also makes clear that when she had originally left Hollywood she had planned to stay away forever. Landi said, “I had no intention of ever returning to pictures, but this picture intrigued me. I knew right then and there that I had a job to do, a bit of work that would have its own unique importance in the war effort.” Far from a comeback film, Corregidor would be Landi’s Hollywood swansong.

She’d appear in two other Broadway plays, Apology, which lasted just 8 performances in 1943, and Dark Hammock, which went off just twice in December 1944. In between those two productions Landi married a second time, to author Curtiss Thomas at Christ Methodist Church in New York City, August 28, 1943. With Hollywood and Broadway behind her, Landi continued to act in Summer Stock as late as 1947, when she appeared as Elizabeth Barrett in The Barretts of Wimpole Street at Woodstock, N.Y.

I can find six novels credited to Elissa Landi. The first at age 19 in London, where each of her first two books, Neilson and The Helmers, were published. Her third, House for Sale, was published in the U.S. in 1932. At the height of her fame in 1934 The Ancestor was published and even rated a review in the Arts & Literature section of The Salt Lake Tribune, placed directly under a review of Hugh Walpole’s latest work. While The Ancestor involved “a complex love situation” told in an “entertaining manner” by Landi, “It has not that sense of reality that marked her study of English life in House for Sale, nor the charm that pervaded it.” Landi’s fifth novel, Women and Peter, was published in 1942. Finally I found no reference to The Pear Tree, but used copies of the 1944 novel for sale on Amazon.com so it most definitely exists!

Curtiss Thomas was at Landi’s bedside when cancer claimed her life on October 21, 1948. She was just 43. The cancer that killed Landi started in her abdomen before spreading to her brain. The condition was kept from her, described only as a chronic condition, for nine months prior to her death. Her doctor credited husband Thomas with doing “a wonderful job in keeping it from her.” Landi was admitted to the hospital October 10 but her condition did not become critical until just 36 hours before her death, the last 24 of which she had slipped into unconsciousness.

So talented, Elissa Landi conquered each the stage and publishing houses of both London and New York and enjoyed a Hollywood career which saw her shoot to stardom before fading away just as fast. Acclaimed for her beauty, her blonde hair and blue eyes gaining mention in almost every article introducing her, let us not forget it was her talent which sprung her from the London Stage to Broadway to Hollywood in the practical blink of an eye. Thanks to the U.S. government going after her for a few more tax dollars we know she made $97,363 in 1934, a time which was perhaps the peak of her career and documentation that she was well-compensated during her stardom. She was given the royal treatment entering Hollywood and because of her questionable birthright may have been more deserving of it than most. Despite her relatively quick fade from movie glory her intellectual activities kept her busy and kept her name in the papers throughout her short life.

Besides the books and articles linked throughout the text, as well as info from Elissa Landi’s IMDb and IBDb pages, several original newspaper articles were accessed through NewspaperArchive.com and used in culling information for this article. They are:

- “Actress Landi Hurt When Her Car Skids.” San Antonio Light 20 December 1938: 11.

- “At the Theatres.” Kerrville Times 16 April 1931: 8.

- “Claims to be Royal Princess.” Boston Daily Globe 18 April 1915: 71.

- “Elissa Landi Buys Peter Sharp Farm On Kingston Flats.” The Kingston Daily Freeman 28 April 1939: 1.

- “Elissa Landi Dies At 43: Had Cancer.” Indiana Evening Gazette 21 October 1948: 1.

- “Elissa Landi Divorces ‘Liberal-Minded’ Mate.” Oakland Tribune 9 May 1935: 1.

- “Elissa Landi, Former Screen Star, Author, Cancer Victim.” Waterloo Daily Courier 21 October 1948: 19.

- “Elissa Landi Is Dead At Home, In Kingston, N.Y.” Dunkirk Evening Observer 21 October 1948: 1.

- “Elissa Landi Is No Hollywood Prima Donna.” Ames Daily Tribune-Times 10 July 1937: 8.

- “Elissa Landi Makes Comeback in Popular War Production.” Ogden Standard-Examiner 27 June 1943: 13.

- “Elissa Landi Settles U.S. Income Tax Suit.” Oakland Tribune 5 March 1938: 3.

- “Elissa Landi Wishes Story That She Is Grand Daughter Of Queen Had Not Been Told; ‘Stands On Own.'” Big Spring Daily Herald 24 April 1932: 4

- “Elissa Landi’s Life, Which Began in Vienna, Has Been Unusually Colorful.” The Daily Mail 30 October 1939.

- Heavy, Hubbard. “Screen Life in Hollywood.” Galveston Daily News 29 May 1935: 4.

- Henderson, Jessie. “Hollywood Is to Have Its Own Royal Family.” Appleton Post-Crescent 28 September 1931: 5.

- “Husband Sues Elissa Landi.” Nevada State Journal 2 December 1934: 1.

- “Landi Denies She’s High Hat.” Oakland Tribune 31 October 1934: 11.

- “Love and the Artist.” The Salt Lake Tribune 2 September 1934: 39.

- “Mystery Ship Seeking the Treasure on the Lusitania.” The Davenport Democrat and Leader 28 August 1923: 12.

- “New Yorkers Buy Elissa Landi Home.” The Kingston Daily Freeman 10 June 1949: 1.

- Parsons, Louella O. “Elissa Landi Decides to Free Lance in Films.” San Antonio Light 26 October 1933: 8.

- “The Secret of an Empress.” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette 20 December 1914: 51.

- Thomas, Dan. “Elissa Landi, Granddaughter of an Austrian Empress, Now Lives Like Hermit in Hollywood.” Sandusky Star Journal 29 December 1931: 2.

- Thomas, Dan. “Meet Hollywood’s Most Versatile Woman.” Laredo Times 23 August 1935: 15.

[phpbaysidebar title=”Elissa Landi on eBay” keywords=”Elissa Landi” category=”45100″ num=”5″ siteid=”1″ sort=”EndTimeSoonest” minprice=”19″ maxprice=”399″ id=”2″]

Leave a Reply