“My love has lasted longer than the temples of our gods. No man ever suffered as I did for you. But the rest you may not know. Not until you are about to pass through the great night of terror and triumph. Until you are ready to face moments of horror for an eternity of love …” – Karloff’s Imhotep to Zita Johann’s Anck-es-en-Amon in The Mummy (1932)

“Moments of horror for an eternity of love” could stand on its own as the short entry for the Universal horror classic The Mummy which condenses Imhotep’s 3,700 year journey into a 70-plus minute atmospheric masterpiece of terror, and yes, romance.

Boris Karloff as Imhotep over Princess Anck-es-en-Amon's (Zita Johann) body in the flashback sequence illuminated through Imhotep's pool.

Personally there’s always been something about The Mummy which made it stand out for me more than it’s great predecessors in the Universal horror cycle, Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931). It’s unusual, though not in the strange ways of Frankenstein’s lab, more in a foreign sort of way. Yes, it’s set in Egypt, so while the foreign feel should be expected I still think it’s accomplishment should not be overlooked.

The studio bound scenes are enhanced by an overwhelming variety of ancient props and interesting sets while the exterior scenes of Egypt were filmed on location in the Mojave Desert which certainly passes as desert enough for me. Layered on top of the perfect images was what I found to be a deceptively creepy soundtrack. There were no jarringly fake backgrounds to distract, the movie never made me feel as though I was anywhere but Egypt, a feat which serves to make Karloff’s character all the more terrifying. With no reason to doubt the place I never felt reason to doubt the situation. Every scene evokes the proper time and place.

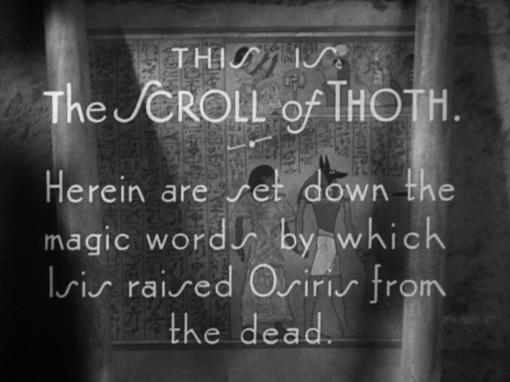

In the opening that time is 1921 and it is then that we see Karloff’s Mummy, featuring Jack Pierce’s incredible wrap job, come back to life in what is possibly the most terrifying scene of any of the 30’s horror classics. The scene is noted for the skill of Director Karl Freund’s showing very little: We see Bramwell Fletcher’s character translating what he’d previously called the mumbo-jumbo of the ancient Scroll of Thoth; An eye opens on the otherwise still Karloff, whose hands then drop from the tattered cloth which had wrapped them for millennia; Fletcher continues to decipher, pausing to peer left; We are shown only Karloff’s hand as it enters the shot to retrieve the Scroll; Fletcher lets out a scream that surely stiffened backs in late 1932 before cascading laughter begins his descent into madness; Only the Mummy’s trailing few bandages are seen being pulled across the floor as he exits, otherwise unseen by us.

The scene actually reminds me of what Wellman had done earlier in The Public Enemy (1931) when Cagney snuffed out Putty Nose. In that shot the camera swings across the room but carefully sticks to Edward Woods while Cagney’s shots are fired. In The Mummy the camera crawls more than it swings, but the general idea is the same, allowing the audience to create the terror in their minds rather than just splattering it across the screen. In fact there’s a whole lot more for us to think about in The Mummy’s use of the technique as it is implied that what Fletcher saw would drive anyone mad including, I assume, the viewer. This is stated later on when Edward Van Sloan’s Doctor Muller tells Arthur Byron’s Sir Joseph Whemple that he too would have been driven to insanity had he stayed at his young assistant’s side during those moments.

It’s these first ten minutes or so of The Mummy, of which we actually see Karloff for maybe a total of 60 seconds, that leaves us with the iconic Mummy image of today.

At this point in the movie I can easily imagine an early 30s Dracula-Frankenstein fan rubbing their hands together and saying Here we go before winding up being disappointed at what follows. Any following horror pales in comparison to this great opening, but I really hope our period fan would have gotten over that and returned to see The Mummy once more, enjoying it as a whole.

With the Mummy awake and presumed stolen we jump ahead to 1932 and the story that unfolds is often somewhat dismissed as a retelling of Dracula. I wonder if this wouldn’t be so glaringly obvious if Edward Van Sloane and David Manners weren’t playing the same type parts in each film. An excellent essay that you can find online for free, The Mummy in Context by Richard Freeman, includes a chart drawn from the similarities mentioned in The Mummy section of the indispensable Universal Horrors by Tom Weaver, Michael Brunas and John Brunas:

But what of the differences? I already mentioned how much more realistic I felt the overall setting of The Mummy was, though I’m certainly not going to knock Dracula for atmosphere! But while Dracula is dark, so dark that black and white is almost a requirement, The Mummy is more of a visual feast. Parts of The Mummy may have been even more spectacular had it been filmed in color, though I don’t think the horror elements would have come off as strong had they done that. Also those myriad props and sets that I wondered over earlier probably would have lost a lot of their luster being exposed as cheap trinkets, so in the end I’m thankful that it is a black and white movie.

Each of these films has its particular atmosphere brought to life before our eyes through their monster, the centerpiece of all that atmosphere. Lugosi’s pale features are set off by his dark costume and that slicked back black hair, while each of Karloff’s faces is rich in detail, a story in and of itself. Each film’s background perfectly accessorizes each particular monster. Combine Karloff’s appearance with his slow movements and speech and I think Ardath Bey/Imhotep becomes one of the most unnerving characters you’ll find throughout screen history.

But while I feel the need to point out what I think is important about The Mummy, what draws me to it personally, I really don’t want to find myself regurgitating what critics have been saying about the film for the past 75-plus years. What fun is that? Blogging about an indisputable classic is only fun if A) the writer hates the movie, which obviously I don’t, or B) the writer gets personal, and in the case of something as celebrated as The Mummy even the latter stance is an invitation to unoriginality. I’m hoping the area in which I can have a somewhat unique take on The Mummy lies between the great gap in time between my most recent viewings of it.

Now I know I must have watched The Mummy five or six years ago back when I originally bought the DVD that I pulled off my shelf this week, but then again I have plenty of unwatched DVDs (they’re getting to be like books, status perpetuated through quantity), so it’s very possible I did not. Perhaps even this week’s viewing of The Mummy was my first since kiddie time in the late 70’s, when thankfully Karloff etched his way into my consciousness by being force fed to me through a limitation of TV channels and a Dad who knew the right stuff to tune into!

Those childhood memories placed The Mummy strictly inside the horror genre. I remembered what everybody remembers: the terrifying opening and the later scene at Imhotep’s pool where he shows Helen/Anck-es-en-Amon his unfortunate fate in their original lives. I didn’t remember the middle of the film, couldn’t recall Manners, Byron, or even Van Sloane, and I must admit that even memories of the climax were faint. But at this point of the post I look back upon the Imhotep quote I chose to open with and conclude that my own placement of The Mummy has shifted somewhat over the decades. That “eternity of love” drawn clearer by Zita Johann’s line “No man has ever suffered for woman as you have for me” and Karloff again, “It was not only your body I loved, but it was thy soul,” now ring as memorable as the reanimated Karloff’s eye opening for the first time or Fletcher’s following screams.

The romance of the film is found inside the ancient scene played from Karloff’s pool. A silent montage looking like something Griffith would have released a generation before (Didn’t the Princess’ father remind you of Belshazzar from 1916’s Intolerance?) and sparsely narrated by Karloff’s Imhotep shows us a third face of Karloff, as a young, living Imhotep, taking the steps which would lead to his being entombed alive for so many centuries.

The section opens with Imhotep at the side of the Anck-es-en-Amon, already dead, as Karloff tells us “I knelt by the bed of death.” Her body is shown being carried to her tomb while a brokenhearted Imhotep oversees the ceremony. Karloff’s says “I knew the Scroll of Thoth would bring thee back to life …. I dared the gods anger and stole it.” Imhotep is caught beside Anck-es-en-Amon’s tomb reciting “the spell which raises the dead,” at which point the Princess’ father has him wrapped alive inside Mummy’s bandages as Karloff writhes under his fresh packaging. In a brutal scene the live Imhotep is entombed while not only are the slaves who oversaw the process killed, but their murderers killed as well, so that no one would carry recollection of Imhotep’s “nameless death.” Just before snapping Helen out of her trance Imhotep tells her as Anck-es-en-Amon, “My love has lasted longer than the temples of our gods. No man ever suffered as I did for you,” and suddenly the monster becomes a bit more human.

I found myself watching Zita Johann closely throughout this viewing of The Mummy. She gives an interesting performance as Helen Grosvenor/Princess Anck-es-en-Amon highlighted by a series of sometimes strange facial expressions. While Helen is supposed to have fallen in love with David Manners’ Frank Whemple, I still found the series of queer looks she passes over him, ranging from disgust to outright laughter, strange, despite her being under Imhotep’s spell. Even if induced by Karloff’s incantations the Princess’ passion for Imhotep sure seems to burn a lot brighter than does Helen’s for Frank!

Beyond Imhotep’s influences Johann’s Helen really struck me as a woman in control. Perhaps my favorite moment for the character, aside from any interaction with Karloff, comes as she professes her love for Frank only to have Edward Van Sloane’s Doctor Muller bust in to remark that she knows more than she’s letting on and that he understands. The call from Imhotep is too strong for her to resist and since the Doc can’t find the undead Karloff himself she should feel free to follow her impulse and lead the men to him so they can dispose of the monster once and for all. She thanks Muller for his understanding, more or less brushing Frank aside. The lovesick dope sits outside her room hoping to overcome the powers of Imhotep through an amulet of Isis that Muller has given him, but of course Imhotep’s need for the Princess sees that his eventual call to her is answered.

Speaking of Van Sloan’s Doctor, just why is Helen in his care anyway? I get that she didn’t want to accompany her British father to the Sudan, where he’s Governor, and it makes sense that she’d want to see Egypt because she’s descended from there on her mother’s side, but why is she with the Doctor? There’s no romantic relationship hinted at there (thank goodness!) and it’s mentioned that Helen is in the Doctor’s care, but for what? I’d have assumed Muller’s doctorate was academic, and I believe it was mentioned that the occult sciences were his specialty, so what is he, her psychiatrist? Her medium? If this detail was given out and I missed it please let me know below.

The perfect explanation of The Mummy’s quality comes from film historian William K. Everson’s closing comment in the brief Mummy section of his 1974 Classics of the Horror Film: “If one accepts The Bride of Frankenstein for its theatre and The Body Snatcher for its literacy, then one must regard The Mummy as the closest that Hollywood ever came to creating a poem out of horror” (93). I’ve always loved this line and remember it well because I’d at one time quoted an abridged, or let’s face it customized, version of it to a buddy back in college. Well it turned it this would be my best buddy from college and we still talk over a dozen years later. Wouldn’t you know he still repeats this quote to me when discussing classic horror, in fact I’ve probably heard it more from him now than I’d ever said it myself! Oh well, glad to know that with Everson I was stealing from one of the best!

Helen (Johann) is immediately drawn to Ardath Bey (Karloff). Looking on are Sir Joseph Whemple (Arthur Byron), Doctor Muller (Edward Van Sloan) and Frank Whemple (Manners) stands on the right.

Universal’s The Mummy runs 73 minutes and was directed by Karl Freund, best remembered as a cinematographer today (he had previously filmed Dracula). The script was based on a story, Cagliostro, written by Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer at Universal head Carl Laemmle Jr.’s request. The screen adaptation was done by John L. Balderston who had also adapted both Dracula and Frankenstein for Universal. Made at a cost of just under $200,000, The Mummy was released December 22, 1932 (Merry Christmas!) and seems to have generally been received as unremarkable by critics of the day. Sequels would follow, though none during this early cycle and no others with Karloff, the first appearing eight years later with the release of The Mummy’s Hand (1940).

I think our fathers had similar taste in movies.

Will, as mentioned on Twitter, I think we grew up watching a lot of the same TV movies … and Dad controlled the TV channels by me!

Without hitting the books, it’s the missing footage of the many re-incarnations of Johann’s character that I wish would re-surface for us to see today. I say that about so many older films and the lost footage that was supposedly shot but after being edited is lost to time.

Probably no surprise, but I’d love to see that too, Mike! Though I am still pretty happy with the total end product in this case. It’s one of my favorites. Thanks for checking out the post!

Though i heard there was a visual scene that was deleted with a lion’s den. What’s up with that?

Hi Stephanie, this would have been part of what was cut from the Anck-es-en-Amon flashback scenes. Any details I give you would be from the Universal Horrors book by the Weavers and Brunas, but luckily that page seems to be available for preview in Google Books. Just in case this link doesn’t show up properly it begins with the first full paragraph on page 67, beginning “Rich in descriptive detail,” with info running halfway into the second column on the page. Enjoy (great book, by the way!).