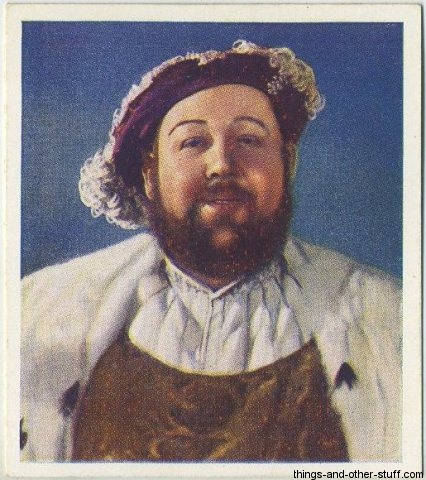

Which Charles Laughton do you remember best? The ill tempered Captain Bligh of Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) who raged at Gable’s Fletcher Christian fiercer than any storm encountered, or perhaps the sweet Ruggles of Red Gap (1935), the poor man Friday transplanted from his familiar British ideal to the rough American Northwest through the fate of his master’s poker hand? Then there’s the masterful Oscar winning performance in the title role of The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) where the dominant Laughton laughs, loves, and certainly eats hearty carving out his place in cinema history at the dinner table of all places. How about his heavily made-up Quasimodo swinging from the bell tower and rescuing his fair Esmeralda in 1939’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame where he reprises one of horror icon Lon Chaney’s signature roles and brings even more humanity to it. Maybe another, I’ll likely mention it here.

Perhaps as Chaney’s unlikely successor is the best place to start as both towering talents are often labeled character actors and while accurate in both cases it didn’t necessarily start out that way for Laughton who was a shooting star on the London stage before ever finding his way to film. From working class roots, his parents managed the same Scarborough, Yorkshire hotel in which Laughton was born, July 1, 1899. Laughton would serve in the First World War, where he was gassed, and go into the family business after that, not entering Drama School until 1925. He’d have his first professional work the following year and as soon as 1927 would make a name for himself during a year which saw him appear in seven new West End productions, the last of which, Mr. Prohack, would bring Laughton fame and begin his complicated relationship with Elsa Lanchester, his wife from 1929 until his death in 1962.

Charles Laughton Movie Cards & Collectibles in my eBay Store

Laughton would appear in some minor British films in the late 1920’s and early 30’s, but his film career wouldn’t really kick off until he came to America in 1931 where he initially appeared on the New York stage. 1932 would be a busy year in Hollywood for Laughton as he appeared in a couple of thrillers, Universal’s The Old Dark House and Paramount’s Island of Lost Souls, plus played one of the best scenes in the Paramount’s 8-episode star-studded If I Had a Million, where his Phineas V. Lambert memorably gives his boss the raspberry on his way out the door. Finally he’d play the part of Nero for Cecil B. DeMille in his blockbuster historical epic, The Sign of the Cross, starring Fredric March and Claudette Colbert who has her own memorable moment in a pool of asses’ milk.

Film stardom came when he returned to Britain to play the lead in Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry VIII, the screen role most closely identified with Laughton, at least during his lifetime, and the one for which he’d become the first British actor to win an Academy Award, as Best Actor in a Leading Role in 1934. Laughton carried a film which would buoy the entire British film industry, introduce us to Robert Donat and Merle Oberon, and kickstart the career of Korda whom Laughton would also appear for in Rembrandt (1936) and the ill-fated I, Claudius (1937), both times, again, in the title role for Korda.

In between his outings as Henry and Rembrandt for Korda, Laughton appeared in some of his best Hollywood productions as well including the aforementioned Ruggles for Paramount in 1935, and then a trio of roles played so dastardly that we can’t help but to continue to be fascinated by them today–as Norma Shearer’s possessive and perhaps even incestuous father in The Barretts of Wimpole Street in 1934 for MGM; as the obsessed Inspector Javert hounding Fredric March’s Jean Valjean in 1935’s Les miserables for 20th Century; then back to MGM and Oscar nominated once more for his Bligh in Mutiny on the Bounty, which would receive 8 nominations from the Academy in all (including Best Actor noms for Laughton, Gable and Franchot Tone, all losers to Victor McLaglen’s Gypo Nolan of The Informer) winning only one, but the big one, for Best Picture in 1936.

Of these more nefarious parts which Laughton often found himself playing he said:

“On the screen I generally have been cast, mostly by my choice, as a wicked, blustering or untidy character. Now I am ready to admit that in real life Charles Laughton is all of those things.

“I often bluster. I find it gets me my own way. I am notoriously wicked–especially to bores.

“I purposely go in for villainous roles on the screen to find an outlet for the evil aspects of my own character. They appear in my own life considerably diluted. This makes life a lot easier on my wife” (Finnigan).

Certainly untidy in 1939’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Laughton also starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn that same year. It would be Hitchcock’s last British release before coming to America, but Jamaica Inn was far from a smooth production with Laughton taking too much control and causing Hitchcock to famously lament that it “isn’t possible to direct a Charles Laughton film, the best you can hope is to act as referee.” Laughton’s problems with Hitchcock harkened back to what was the early criticism of his stage work in Britain, a period extensively covered by Laughton biographer Simon Callow, which paints a picture of the late blooming Laughton as unprofessional in the word’s most literal meaning: he was respected as an artist, but his skills and talent came from within himself, not through any sort of learned mastery of his craft. Despite Hitchcock’s disdain the two would work again in 1947’s The Paradine Case in America, a lesser Hitchcock with a lesser part for Laughton which kept him out of the director’s hair.

The following decade would be a mixed bag for Laughton’s career, certainly an overall let down after the classic roles throughout the thirties. Still, Laughton was once again wonderful in another episodic picture, this time as the orchestra conductor in Tales of Manhattan (1942), then there was the enjoyable action romp, Captain Kidd (1945) where he played the title character which he would reprise in 1952’s Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd, of which Lou Costello said he was “afraid to ask this great actor to do some of the hokum we had in the movie but after the first day, he was showing me how to hoke up the slapstick for more belly laughs” (AP). Laughton had parts in a couple of fine thrillers at the end of the forties as well, Paramount’s The Big Clock (1948) and MGM’s The Bribe (1949).

In Charles Laughton: A Difficult Actor Callow points out the divide in his career, pre and post-Quasimodo, writing that there’s nothing wrong with what came after The Hunchback and that “the remaining performances would seem intelligent, well-observed, powerful, striking, often moving, and always, even at their very least inspired, watchable; but … in none of them does Laughton function as a primary creative artist, as he did in Nero, Bligh, Barrett, Quasimodo, even Phineas V. Lambert. In short, from now on he put his talent into his acting, his genius elsewhere” (141).

There still were a couple of great screen performances to come, back to Britain for the at once hilarious and touching Hobson’s Choice (1954) and as one-third of the masterful triangle along with Tyrone Power and Marlene Dietrich in Billy Wilder’s Witness for the Prosecution (1957), but what Callow’s referring to goes beyond even Laughton’s acclaimed directorial debut and lone such effort on screen, The Night of the Hunter (1955). A series of daring off-screen projects filled Laughton’s resume from the late 1940’s throughout the decade of the 50’s.

Laughton would direct on Broadway, most notably The Caine-Mutiny Court Martial starring Henry Fonda with whom he had an acrimonious relationship that continued silently on the set of Laughton’s final film, Advise & Consent (1962). But the genius came out in more original projects such a collaboration with author Bertolt Brecht in bringing Brecht’s The Life of Galileo to the stage in 1947 and the 1953 staging of John Brown’s Body, an epic poem by Stephen Vincent Benet starring Tyrone Power and giving him the type of role he’d long craved. The period was filled with even more interesting efforts such as the series of readings he gave on stage, his intonations making even Bible stories prove interesting to capacity audiences in small venues across America. Laughton played the Devil and directed Don Juan in Hell in 1950, the rarely performed third act of Shaw’s Man and Superman, which was a rousing success. The work Laughton chose was original and daring, seemingly destined to flop, but these labors of love were usually pulled off with success. One of his final projects was a highly acclaimed one-woman show he created for his wife in 1960, Elsa Lanchester – Herself.

In a career spanning 1926 through his death, December 15, 1962, Laughton, to contradict Hitchcock, mastered acting on stage and screen, plus he was a successful director in both mediums, and he would teach, write, and record as well–that voice was meant for records and Laughton made several reciting some of his favorite pieces, a passion he’d had since the time he spoke the Gettysburg Address in Ruggles of Red Gap. Speaking of Gettysburg, perhaps in the end the land of Ruggles suited him best: Laughton and Elsa Lanchester would become proud American citizens in 1950.

Looking back on those 36 working years as a whole as I’ve attempted to do here really paints Laughton as an all around creator, and while some of his better remembered performances may sometimes lean towards going over the top, really would you want anything less out of your Captain Bligh or Henry VIII? A fantastic artist and natural talent, a real genius of the arts.

Charles Laughton Movie Cards & Collectibles in my eBay Store

A few quotes from co-workers found in the Laughton obituaries:

“Charles was a great grizzly bear and he vainly tried to hid his big, pink plush heart.” – Agnes Moorehead

“I doubt if Mr. Laughton had any foes. He always frightened me and other people in our industry, but only by his great talent.” – Joan Crawford

“Laughton was an actor who dared. The modern trend in acting is to underplay and as a result many actors come up doing nothing. But when Laughton was on the stage or screen you knew it.” – Kirk Douglas

Sources:

Callow, Simon. Charles Laughton: A Difficult Actor. New York: Grove Press, 1987.

Finnigan, Joseph. “Laughton Loses Battle With Cancer.” Clovis News-Journal 17 December 1962: 10.

“Cancer Claims Charles Laughton.” Kingsport Times 17 December 1962: 1.

“Charles Laughton Dead; Film World Pays Tribute.” The Bridgeport Post 17 December 1962: 48.

Also of Interest:

Rooting for Laughton

Charles Laughton on the IMDb

Charles Laughton on Wikipedia

Charles Laughton Movies for Sale on Amazon.com

Leave a Reply