When it was released in late 1933 The Sin of Nora Moran was unlike anything theatergoers had ever seen. Too unlike for success. The movie came and went, a box office failure that left critics confused.

Considered by some to be an early Hollywood art film, most of what earned The Sin of Nora Moran that tab came of necessity. The Poverty Row release made expert and extensive use of stock footage, weaving in material more seamlessly than most films from major studios did. Its sparse and simple sets are highlighted by lights and darks, often fire and shadows, and the transition from most every scene is accentuated through a vast inventory of editing technique. Most noticeably the story is further dramatized by being told out of order in an escalating, often nested, series of flashbacks and flashbacks within flashbacks that sometimes even feature the main character struggling to change what has already happened.

No matter their audience, reviewers just didn’t get it in 1933.

Fan magazine Photoplay referred to The Sin of Nora Moran as a “grief-laden story” that was “depressing and confusing.”

Trade publication, Film Daily also said that the theme was “too full of grief” and that the continuity was poorly handled. They did praise the actors and informed exhibitors that it had possibilities “from an exploitation angle.”

Mainstream critic Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times agrees with the others when he calls The Sin of Nora Moran “very muddled” and states “parts of it are apt to be exceedingly depressing.” He directly refers to Fox’s The Power and the Glory, released just over two months earlier, and states that by comparison “the current offering … besides having little in the way of entertainment, lacks the clarity, the efficient acting and the good writing,” of Fox’s “narratage” film that starred Spencer Tracy from a script by Preston Sturges.

But the passage of time has been very kind to The Sin of Nora Moran. I was so impressed when I first found this movie that I watched it three times within a two-day period. Then I let it sit a few weeks to get some distance and came back only in advance of writing this article: I enjoyed it just as much as I had the first time.

The Sin of Nora Moran is my favorite new discovery of 2014.

It’s a Poverty Row film made by Phil Goldstone at Majestic Pictures for release in late 1933. In an unusual twist, studio owner and lead producer Goldstone also directed The Sin of Nora Moran. It is a public domain title that I picked up for under $4.00 during an Alpha Video sale, but you can even see it for free online. Despite this easy access The Sin of Nora Moran has somehow only accumulated just over 160 IMDb ratings at the time of this writing. We need to grow that number.

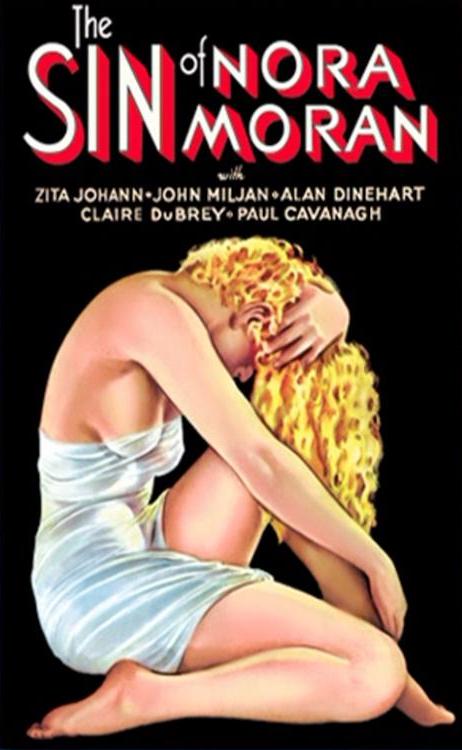

It’s greatest fame today is its sexy poster art by Alberto Vargas (above) that somehow, despite the relative unknown status of the film it promotes, continues to be appreciated as one of the greatest pieces of poster art of all-time. I’ll be honest, that image was part of what lured me to the title while browsing the Alpha sale, but I wound up not expecting much out of the movie itself based on the quality of a couple of other Alpha offerings that I watched first. By the time I got to The Sin of Nora Moran my only hope was that it wouldn’t suffer from a terrible transfer with scenes that were obviously missing like those other titles, namely Morals for Women (1931) and A Girl of the Limberlost (1934).

Not so with Alpha’s release of The Sin of Nora Moran. It is a crisp copy and despite running just 64 minutes would appear to be complete.

In this short running time we witness all of the key moments from Nora Moran’s life and death, though not necessarily in that order.

We follow young Nora, played for one scene by six-year-old Cora Sue Collins, out of an orphanage and into the arms of a loving family, who provide happiness until their death in a terrible car wreck. Nora, now grown-up and played by Zita Johann of The Mummy (1932), returns to the orphanage to ask Father Ryan (Henry B. Walthall) if she should pursue her dream of dancing. His consent falls short of a blessing, but Nora pursues her career on stage and quickly meets failure and disappointment. Opportunity knocks when she sees an ad for a traveling circus act, which she joins as assistant to lion-tamer Paulino (John Miljan). “All you have to do is wear that outfit and look pretty,” Paulino tells her.

Life was happy again for Nora in the circus until one night when Paulino stumbles drunk into her train cabin and rapes her. Nora leaves the circus immediately and goes to New York where she takes a job in a night club. There she meets a man who she really falls in love with, Dick Crawford (Paul Cavanagh). Dick loves her too but not only is he married, he’s a candidate for Governor and so the affair is ill-advised. Nonetheless he sets Nora up in a house across the state line and visits her every Monday and Friday, a set-up that works until Dick’s brother-in-law, the District Attorney John Grant (Alan Dinehart), decides to check up on him. His arrival sets off an evening of tragedy that inevitably leads to the only thing that could ever split Dick and Nora, murder.

But the opening of The Sin of Nora Moran takes place well after all of this has already happened.

Dick’s wife, Edith Crawford (Claire Du Brey), visits her brother, John Grant (Dinehart), at his office. She carries a stack of unsigned love letters from Nora to Dick that her brother quickly confesses to knowing about. District Attorney Grant then begins telling his sister the story of Nora Moran. We eventually trail away from Dick and Edith, across the office and into the fireplace where we follow the flames as they smolder superimposed over Nora’s face. Now we’re with Nora in her cell on Death Row as she awaits her execution. Dick Grant continues to narrate Nora’s story, but given the intricacy of the flashbacks much of what occurs is also to be revealed directly by Nora herself. A bit gimmicky, yes, but not only does it work, the flashback technique becomes vital in revealing several of the twists placed near the end of the movie.

The movie is filled with bizarre scenes and even stranger dialogue, but the pieces fit together in such a way that left me admiring The Sin of Nora Moran for both its freshness and especially its boldness.

An example comes in Nora’s jail cell. A prison matron had attended to Nora in earlier scenes, but upon our return she is being looked over by Sadie, a circus friend known for drinking too much. Nora’s voice is faint as she calls for the matron, Mrs. Watts.

“No, I’m Sadie, don’t you remember me?”

“No, I don’t. Things seem strange,” Nora says.

“That’s because your dreaming,” Sadie explains. “And so far you’ve dreamed things just as they happened, but I thought when you got to me I would change the dream, if you wanted me to.”

“How?”

“By not giving you the money,” Sadie says.

“I don’t understand you.”

“Don’t you remember?” Sadie asks. “After you’ve been with the circus for nearly a year, I found you sitting here one night. I was drunk, but not too drunk to know you were just about ready to bump yourself off. So I gave you a hundred bucks to get away from the circus and Paulino.” Sadie’s voice is soft, her tone tender.

“Oh yes, now I remember,” says Nora. “You were the only one who was friendly to me.”

This flashback featuring Nora with Sadie is featured inside of the story that the District Attorney is telling to his sister. But the flashback is Nora’s dream or fantasy that Sadie has entered for the purpose of giving her a way to change what happened. The tension is heightened because the details of what Nora did have not yet been revealed to us, but despite any possible confusion we want Nora to take Sadie up on her offer to change whatever has put her in this jail cell. But Nora refuses her by denying the situation.

“But I’m not in jail, I’m here,” she says, sitting up from the prison cot, her blanket falling down to reveal she is dressed in her circus costume.

Even in a fantasy this is too much for Sadie, who says, “I guess I better get drunk. I can’t help you.”

In a later scene Nora fights even harder to change her destiny. What seems to be a romantic evening with Dick is spoiled when Nora hears circus music coming from outside. She freezes, terrified at remembering.

“What’s the matter, dear?” Dick asks as he embraces her.

“I know now,” Nora says. “It’s the circus, isn’t it?” She goes to window and sees them pass, horrified as they do. “You must leave. You must leave now,” she begs Dick, but the doorbell interrupts.

“Answer it,” Dick says.

“No, I won’t”

“You must.”

“But don’t you understand? If we don’t see him it won’t happen.”

“It’s too late now,” Dick tells her. “You must answer it.”

“Yes, that’s right,” she says, her tone matter-of-fact. “I must.”

While the Alan Dinehart character, the D.A. Grant, is telling this story to his sister, Zita Johann’s Nora is fighting inside of the flashbacks to remain cognizant of what is to come and to not only relive the joys she experienced but attempt to change the tragedies that put her on Death Row and, most importantly, separated her from Dick.

But it’s not just Nora who fights against Grant’s retelling of the factual past. It’s Dick, who by this time has ascended to Governor of the state and has come to realize that he is a puppet of Grant and even his own wife. In a dark scene Grant and Dick stand over Nora, her body prone inside an open casket with four tall candles seemingly all that lights the scene.

“Come on, look at her,” Grant demands.

“I don’t want to,” says Dick, stepping from the shadows nonetheless. “What’s the matter with her?”

“She’s dead,” says Grant.

“I don’t like the way they fixed her hair.”

“They shaved part of it off,” Grant explains.

“Why?” asks Dick, dumbfounded. “Why did they do that?”

“So the current would go through her head,” Grant says.

“It doesn’t go through her head,” Dick states. He’s horrified by the idea.

“It goes through her head, her arms and her legs.”

“That’s a lie,” says Dick.

“It goes through her head, her arms and her legs,” Grant repeats, adding, “if you don’t believe it, come to the execution tonight. They’re going to kill her again. The warden wasn’t pleased with the way she died.”

And on it goes. An even more bizarre flashback takes place on execution night when Dick is visited by Nora’s levitating head. She invokes Father Ryan’s words about “eternal rest” and “perpetual light” and assures Dick that her death is all for the best. Dick meanwhile tries to summon the courage to issue a last minute pardon, while his conscious is suddenly taken over by the voice of our narrator, his brother-in-law Grant, who plants the idea in Dick’s head that a pardoned Nora would always be a liability waiting to spring on him. “That was his voice,” Dick says. “I didn’t think that, he said it.”

The Sin of Nora Moran was based on a story by Willis Maxwell Goodhue titled Burnt Offering. I had no luck in tracking down this source material and it may have been written expressly for Phil Goldstone and Majestic Pictures. Goldstone only directed a few movies, most of them silent films prior to this, and is best remembered as producer of Majestic horror film, The Vampire Bat (1933). He did some later work at MGM, where big plans (adaptations of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and Herman Melville’s Typee) never came off. Later in his career Goldstone popped up as boss of Phonovision, which appears to have been a failed attempt at a form of home video back when most Americans were just buying their first TV sets.

Prior to The Sin of Nora Moran and Majestic Pictures, Phil Goldstone had been a heavy investor in independent films and was a key party in forming the organization that eventually emerged as the Independent Motion Picture Producers Association (IMPPA) in early 1932. He acquired Majestic shortly after this and became a major player in getting independent films into the theaters.

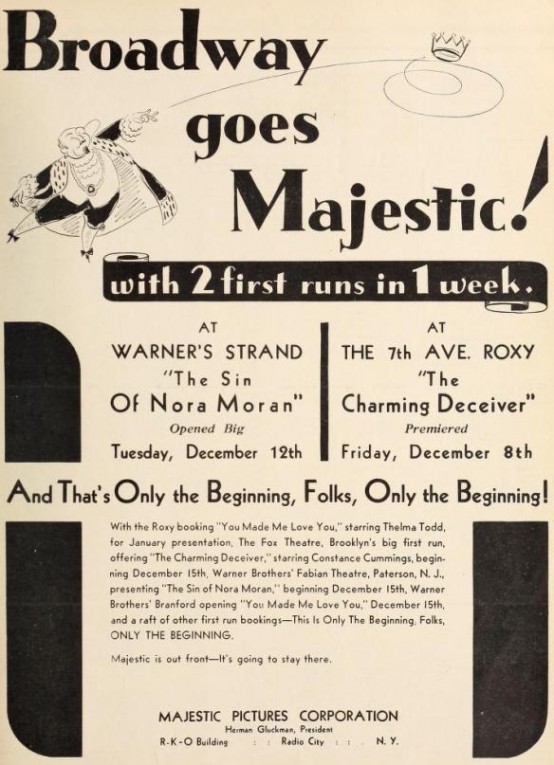

Under Goldstone’s thumb Majestic was known for producing better quality product than most Poverty Row companies could. Majestic movies were intended to be good enough to fill the top half of the double features that had made a comeback with the public during with the early days of the Great Depression. With The Sin of Nora Moran and a handful of other late 1933 Majestic releases, Goldstone aimed even higher and this film actually had its premiere at the Strand Theater in New York. As mentioned earlier it would flop with critics and public alike.

Majestic ad inside Film Daily, December 14, 1933 issue. Found through Lantern search engine.

The production cycle was fast. In their June 15, 1933 issue Hollywood Reporter notes that Majestic had arranged to borrow John Miljan from MGM; The following day Film Daily reports that Zita Johann has been signed to play the lead; On June 20 Hollywood Reporter reports that Goldstone has taken over directorial duties himself; On June 30 that same publication reported that Goldstone had brought the production to a close four days ahead of schedule.

Besides Phil Goldstone’s fine hand on what is an interesting story arranged to carry off twists and turns to maximum effect, The Sin of Nora Moran is filled by an excellent cast of actors who were more accomplished within their profession than they ever were famous with the public.

Alan Dinehart is especially strong as narrator and, inside the flashbacks, featured player. His District Attorney Grant is a power-hungry politician whose ambition is tempered somewhat by a recent brush of lasting empathy for Nora Moran. Former silent star Claire Du Brey holds her own across from him as the Governor’s vengeful wife, Edith. Despite Edith’s anger Du Brey offers a willing enough ear for her brother to tell us this tragic story. Paul Cavanagh excels in the more bizarre scenes of the story, when he more or less speaks his moral dilemma out loud and openly questions the path he should follow. John Miljan’s appearance is brief but devious–The movie features two action-packed brawls, one of them between Miljan and a lion! Henry B. Walthall isn’t even around as long as Miljan, but he’s very good at playing kindly older men such as Father Ryan by this late point of his career. Despite Dinehart’s extremely strong presence The Sin of Nora Moran hinges on Zita Johann’s carrying off the lead, and that she does.

It’s a performance filled with anguish, which having spent the past month watching Zita Johann’s other few films I would say is her most accomplished emotion. But beyond all of the time she spends tossing in torment on her prison cot, Johann must also relive the entire life of her character, ups and downs alike. Fear and horror are easily spun from her anguish, but she also pulls off a classic hardboiled entrance after her arrest and, while with Cavanagh, is able to present a heavily tempered joy. Perhaps her best such moment comes soon after Dick places Nora in her own house, out of the way so he can visit her. He’s startled to find her crying and Nora, fighting through her tears, explains, “The stove works. And the radio works. And the fireplace works and it’s so lovely to have a house with things that work, I can’t stand it.” She buries her head into his chest. Her joy is the purest joy, contrasted by the misery of her life, past and future, and the disbelief that something good could come of life. It’s really fantastic work by Johann and I was upset to see her discount it by completely brushing over the title in conversation with her biographer Rick Atkins in Guest Parking: Zita Johann

It’s a performance filled with anguish, which having spent the past month watching Zita Johann’s other few films I would say is her most accomplished emotion. But beyond all of the time she spends tossing in torment on her prison cot, Johann must also relive the entire life of her character, ups and downs alike. Fear and horror are easily spun from her anguish, but she also pulls off a classic hardboiled entrance after her arrest and, while with Cavanagh, is able to present a heavily tempered joy. Perhaps her best such moment comes soon after Dick places Nora in her own house, out of the way so he can visit her. He’s startled to find her crying and Nora, fighting through her tears, explains, “The stove works. And the radio works. And the fireplace works and it’s so lovely to have a house with things that work, I can’t stand it.” She buries her head into his chest. Her joy is the purest joy, contrasted by the misery of her life, past and future, and the disbelief that something good could come of life. It’s really fantastic work by Johann and I was upset to see her discount it by completely brushing over the title in conversation with her biographer Rick Atkins in Guest Parking: Zita Johann (Not a traditional biography, by the way).

The Sin of Nora Moran is a movie you deserve to discover if you have yet to do so. It is a movie that deserves to be watched and not just once. You can view it on YouTube HERE or at the Internet Archive HERE. If you’d prefer to own a copy, my recommended path, you can pick up the Alpha Video release on Amazon through my affiliate link HERE. If you’ve seen it before and dismissed it I recommend you give it another shot—or two. The structure isn’t as difficult for the viewer to follow today as it was in 1933, however a first viewing brings so many twists, turns and gasps that you’ll really want to check it out again once you have acquired that foreknowledge of what is to come.

For more about the flashback technique David Bordwell’s essay, “Grandmaster flashback,” is essential reading. B-Movie Madness refers to Nora Moran’s “Fellini-like dreamworld” and calls it “well ahead of its time.” At Wonders In the Dark, Allan Fish refers to the technique as “a strange, almost avant garde conceit,” that “works tremendously.” John D’Amico at Homages, Ripoffs, and Coincidences praises both the film and its beautiful and talented star Zita Johann. I especially liked his invocation of Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) because I immediately recognized what he was referring to:

The Sin of Nora Moran is far more appreciated today than in its own time, yet it is desperately in need of an even larger audience to be appreciated as fully as it should be.

JUST MARVELOUS!!!!! I Cannot wait to see it again! Zita Johann is a gem!!!!!!

Thanks so much! It really is a wonderful movie and quite the showcase for Zita Johann (and Alan Dinehart!).

Looks like Burnt Offering was a 3-part story printed in successive The Underworld Magazine issues (beginning with v9 #2, August 1930): http://philsp.com/homeville/fmi/k10/k10408.htm#A1