In Defense of Dracula

My original intention was to write something such as X number of things that still creep me out about Dracula. It quickly became apparent that X would become a very large number as I found myself transcribing almost the entire film to my notes. That was out.

The 1931 film has become too absorbed into our culture to ever truly frighten anyone over a certain age, but it is also true that for modern senses what is presented just isn’t that scary. That doesn’t mean Dracula is without its chills.

While you will never run out of the room screaming, the film should still draw a reaction. Your pulse may race some; the gooseflesh should still prickle. Yes, it does take an effort, a willingness to submit to Dracula, to want to be made uncomfortable by it, yet the same can be said of any gore obsessed teen seeking thrills inside a commercial haunted house come October.

Dracula comes first, as it almost always comes first, inside the indispensable Universal Horrors by Tom Weaver, Michael Brunas and John Brunas. Much to my surprise it is just as quickly dealt a brutal blow:

”The flaws inherent in DRACULA are so self-evident that they are outlined in nearly every modern-day critique; only Lugosi freaks and the nostalgically inclined still go through the motions of praising and defending the film” (26).

I’m quite happy to be counted amongst the latter group. I was fortunate enough to see Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy and so many of the other horror classics when I was still young enough for them to stick. Bela Lugosi is my Dracula. The image is burned into my mind. I’ll accept the more generic vampire in any horrible form, but for me Count Dracula should look like Valentino risen from the dead and sound like Paul Lukas in Watch on the Rhine (1943).

It doesn’t take much more than a gander at the list of classic movies I have previously written about to realize Horror films are not the focus of this website. I write about about mostly pre-World War II film titles and personalities and it’s probably pretty obvious at this point that I often plant myself comfortably some time between 1931 and 1936 or so. This is a home to general nostalgia.

Yet Dracula, released forty years before I was born, arouses a great deal of personal nostalgia in me as well. I do credit the monster movie as my gateway to all of those old movies your friends and family may think of as creaky antiquities. You know better though. You and I are coming from a similar mindset, so let’s shut out those naysayers for a little while and attempt to look at Dracula as though it were any other old movie and not specifically a genre film.

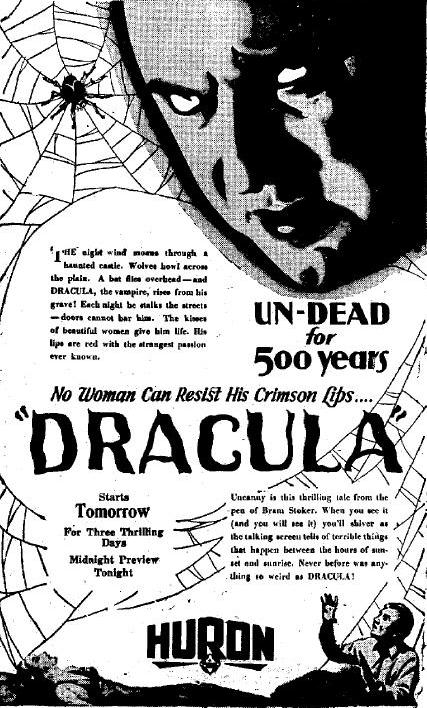

“His Kiss Was Death Yet No Woman Could Resist” from the Charleston Daily Mail, April 5, 1931, page 39

Of course, Dracula isn’t just any other old movie, and so we need to place it in its proper context and dance around the genre a little to get where we’re going.

Dracula was the start of something new. There had been horror films before it, though these seem mostly divided between what came out of Europe and Universal’s own selection of Lon Chaney films, sometimes no more horrific than Chaney’s personalized make-up made them. But those were of another era.

The movies talked now and Dracula would be the first film to really capture the public’s imagination through horrific images that just couldn’t be explained away. In other words, an actual monster.

No detective ever unravels the mysteries of Dracula, rather Van Helsing unravels the unbelievable thing that he is. He speaks the solution to our mystery: “The superstition of yesterday can become the scientific reality of today.” There is no reasonable explanation to what is occurring. It is simply Dracula.

Chew on that, 1931.

Dracula, of course, did not come to the screen from out of nowhere. Based on Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel which was in time adapted for the stage, first in Stoker’s native Britain, and then, beginning in 1927 on Broadway where Bela Lugosi was first cast in the title role. Continuing the earlier quote from Weaver and the Brunases:

”The main problem is that it hews too closely to the play, abandoning many potentially exciting scenes delineated in the novel. Browning is slavish in his faithfulness to the stage production … Any action not seen in the stage production remains off-screen here as well (i.e., Dracula’s flight from the Seward home in wolf form, Mina’s midnight confrontation with the vampire Lucy, Renfield and his army of rats); later descriptions of these events add to the verbiage of an already overly conversational film.

I disagree, especially with the specifics. You don’t have to look much further beyond what is in Dracula to be thankful that it went no further. Even I have to stretch my imagination some to believe Lugosi’s Dracula in bat form. While it probably would have more effective to just have Dracula move about as mist, showing us the bat does add a visual element of the supernatural to the film so I’m willing to buy it. Hesitantly.

But if they manage to test even a willing viewer such as myself with a bat—a simple black fluttering image–how well do you think they would have managed a wolf? Or an army of rats? Am I wrong in picturing a roving wolfhound and a cluster of white lab mice? I’m happy that Browning left well enough alone here.

For fans of this movie era in general the mere suggestion of these scenes not only work, but add atmosphere. Telling us about the rats instead of showing them allows us another moment of Dwight Frye’s masterful Renfield and I’ll take as much as I can get, knowing the sad trajectory of Frye’s career in what should have been the afterglow following Dracula.

The exchange between David Manners and Edward Van Sloan, when Manners’ John Harker comments upon the large dog only manages to add to the credibility of the Van Helsing character played by Van Sloan, who is quite sure of what is going on by that point. If the characters, and more especially the audience, don’t buy Van Helsing, then we’re never going to get anywhere.

While we don’t see Mina’s confrontation with Lucy we do, briefly, see Lucy once more. I’m willing to bet those few seconds were some of the most horrific for period audiences to witness. (I can almost imagine stunned audience members turning to one another to ask if that was indeed Lucy. Isn’t she dead?) Beyond actually seeing Lucy is the revelation of what she’s been up to: The mysterious beauty in white was seen promising chocolates to little girls whom she enticed to a secluded spot and bit in the throat.

In our rush to celebrate the pre-code era of movies we sometimes forget that it was not a time of anything goes. Much more went than did in the lengthy period following that began in mid-1934, but filmmakers were not allowed to put just anything they pleased on the screen.

Dracula, as the first film of the coming cycle, largely drew a pass with censors. By the time of Frankenstein later that same year, code enforcer Colonel Jason S. Joy asked his boss Will Hay if “this [is] the beginning of a cycle that ought to be retarded or killed?” (Skal 162). Luckily Dracula had not gone far enough on its own to either retard or kill the monster movie before it became a trend!

And so in Dracula you do not actually see Lugosi bite any of his victims, nor was there going to be any specific showing of Lucy draining the blood from a pair of little girls.

Just the very idea of these horrific elements was more than enough and while many of Dracula’s concepts, beginning with the idea of the undead, went further than audiences had experienced before the overall tone and presentation of the story itself was consistent with non-genre films of the period.

Sharing Space with Dracula

Dracula premiered in New York on February 12, 1931, but it was far from the only thing worth seeing at the theater that week.

It immediately caught on with audiences and contended with the film which would win 1931’s Best Picture, Cimarron, the epic starring Richard Dix which hasn’t aged nearly as gracefully as Dracula. Cimarron had opened nationally less than a week prior to Dracula’s February 14 nationwide premiere and besides the Academy Award for Best Picture would also be named Film Daily’s Best Picture of 1931. This respected annual poll of the film industry saw Dracula finish tied for 34th behind many titles that you’ve probably never even heard of.There were classics which have stood the test of time better than Cimarron to rival Dracula at theaters at that time as well. The horror cycle had begun just on the heels of the gangster cycle with Little Caesar premiering in January and Edward G. Robinson’s Enrico Bandello often staring across at Lugosi’s Dracula on newspaper pages early that year. Dracula would still be enjoying nationwide success when Cagney came along as The Public Enemy that Spring.

We’ve got gangsters and monsters, how about newspapermen? United Artists released The Front Page in New York that March 19 with an early April nationwide premier. Dracula was still going strong by that time.

If the movies weren’t talking well enough for you yet–no Lugosi wisecracks, please–you would surely be anticipating Chaplin’s latest release, City Lights. The silent film was critically acclaimed from it’s January 30 premier in Los Angeles and would begin its spread nationwide that March 7.

Other popular films around the time of Dracula’s release included Reaching for the Moon starring Douglas Fairbanks–Sr. Not Jr.; The Devil to Pay, also from United Artists and starring Ronald Colman; A double dose of Barbara Stanwyck with Warner Brothers’ Illicit premiering the same day as Dracula nationally and the Columbia release Ten Cents a Dance following at the start of March; The woman’s film with the biggest push at that time was RKO’s Millie starring Helen Twelvetrees, though the trade publications were building anticipation for Gloria Swanson in Indiscreet coming that Spring.

You could even catch Bela Lugosi in a small role in the Olsen and Johnson comedy 50 Million Frenchmen, also premiering Valentine’s Day, 1931.

It was a great time for movies. Early 1931 saw so many released that may seem a little clunky now but offered a great improvement over much of what was seen in 1930. Dracula is not the only film named above which survives til today as a beloved classic.

Dracula, For Scares

You know the story, but just in case you’re not yet familiar with the 1931 version of the film, or have somehow let it slip from your mind, let me give it to you in brief with some of that atmosphere layered in for kicks. The menace immediately begins …

Before we even meet Count Dracula we are warned of him. Mr. Renfield (Dwight Frye) rides a carriage that is so in the middle of nowhere that the biggest surprise is that he even has fellow passengers. These fellow passengers know to fear their neighbor. Renfield is warned: “It is Walpurgis Night. The night of evil. Nosferatu—” before a woman clamps a hand over her husband’s mouth. You see, this evil is unspeakable to some.

But once the carriage lets off its passengers Renfield is warned again, this time by the Innkeeper (Michael Visaroff), one of those unforgettable characters of ’30s films, who leave you wishing for more:

“No! You mustn’t go there. We people of the mountains believe at the castle there are vampires. Dracula and his wives they take the form of wolves and bats. They leave their coffins at night and they feed on the blood of the living.”

At this point of the film, just a few minutes in, I do want you to be sure to have turned out your lights. If you’re watching alone, all the better. This isn’t going to be a blood and guts show. Dracula is largely atmosphere. It is set in the night and beyond the Gothic images that director Tod Browning and cinematographer Karl Freund are about to bring to you, the night simply translates better in black and white. Put yourself in the quiet of the dark and give yourself over to the sounds and images of Dracula. Those sounds are not distracted by any score beyond the opening credits and so you are better left to absorb every creak, howl and flutter to be heard throughout Dracula.

We transition to the silent underbelly of Dracula’s castle, a wide expanse dotted by a handful of coffins. The focus is on one particular coffin in the distance. We move closer to it as the lid slowly rises, long, slender arthritic fingers pushing it open. Jumping away, the other coffin lids begin to rise and we see catch a quick glimpse of some very pale, certainly undead, women before suddenly we are shown the full imposing dark figure of Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula.

Quickly back to Renfield we go.

Renfield rides alone as the original carriage takes him to a connecting carriage at the Borgo Pass. Once Renfield is on the ground, dead of night in the middle of nowhere, the original carriage driver tosses his luggage at him and quickly gets out of Dodge.

The waiting carriage is driven by none other than Count Dracula himself, though Renfield is not aware of this fact. Dracula’s eyes gleam through the foggy night as Renfield nervously gives him his orders and climbs into the carriage. They take off full speed towards Castle Dracula. A nervous Renfield leans out of the carriage window to tell his driver to slow down, and what does he see—not his driver in the form of a man, but as a bat levitating over the reins.

Lugosi delivers several lines of iconic dialogue to Frye’s Renfield once we make it to his castle. “I am Dracula” … “I bid you welcome” … “Listen to them. Children of the night. What music they make.”

You can toss around the word “stagey” if you want, but you will never convince me that Lugosi’s dialogue could have been more effectively delivered in any other way by any other actor.

His slow delivery still manages to keep me on the edge of my seat awaiting his next word. Sometimes even his next syllable. His deep voice triggers my pulse as his every word is coated with menace. Lugosi’s strong accent just makes him seem all the more different, foreign, to me. And after all, no matter how exposed you are to the film, this is Count Dracula. Putting myself in Renfield’s shoes, his bidding me welcome scares the hell out of me.

But in Renfield’s shoes Count Dracula is just an eccentric at this point. There is no menace beyond the (ridiculous!) stories he has heard from the locals. It’s just all very odd to him.

We soon meet a very different Renfield on board the Vesta bound for England. Dracula has had has way with him and made Renfield into the madman that he will remain throughout the rest of Dracula. As a storm rocks the ship’s crew above, Renfield whispers sweet nothings to his master’s coffin, eventually alerting him that the sun is gone.

Dracula rises and soon casts an eye on the busy crew. When the Vesta docks we see the shadow of the Captain, dead and tied to the wheel. The authorities receiving the ship at the harbor assume that there have been no survivors until they hear a high pitched breathless sort of cackling coming from below. “Why he’s mad,” one says as we see Renfield, teeth bared, cackling. “Look at his eyes. Why the man’s gone crazy.”

Renfield is soon locked up at Doctor Seward’s Sanitarium near London, which just happens to adjoin Dracula’s new property at Carfax Abbey. Dracula pays a visit to his new neighbors at the symphony that evening—draining the blood and killing a young flower girl on his way—greeting Seward (Herbert Bunston), his daughter Mina (Helen Chandler), her fiance, John Harker (David Manners), and her friend, Lucy Weston (Frances Dade).

Lucy gives Dracula his open by reciting a morbid poem and Dracula charms his new neighbors in the opera box by sticking to topics he knows and loves: “To die, to really be dead. That must be glorious,” he says, adding, “There are far worse things awaiting man than death.” Pleased to meet you too. The next day Mina mocks his accent while Lucy speaks of how fascinating she found him. Oh, poor Lucy!

Meanwhile Doctor Seward and company are really having a time keeping Renfield under wraps. He somehow manages to escape his cell at will. A sample of Renfield’s blood is taken to a specialist, Professor Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan), who declares, “Gentleman, we are dealing with the undead.”

From there the bulk of the action of Dracula takes place at the Seward home, which is seemingly attached to the Doc’s Sanitarium because Renfield keeps popping in on them. Count Dracula stops by a few times as well. Van Helsing manages to make Dracula a bit edgy after his keen eye spies the odd revelations of a mirror found on the inside cover a cigarette box in the Seward home.

Van Helsing sells Doctor Seward on the vampirism idea, but has a harder time getting Harker to buy in. Especially after Harker’s beloved Mina becomes Dracula’s latest victim and, from his perspective, Van Helsing’s latest experiment. It takes a moment of lucidity on Mina’s part to finally make Harker believe.

Let’s Get Personal

While there can be no argument that the first section of the film far outclasses what follows, Dracula still seems less stage bound than other adaptations of the period.

First to my mind comes the highly acclaimed Street Scene, which I’ve had reason to talk around on a couple of occasions recently, and which, for me, every second reeks of stage adaptation. The same goes for Smart Woman, also 1931. Also MGM’s Private Lives, also, yep, 1931.

Doesn’t make them bad. I don’t know about you, but I wasn’t around to punch my ticket to the original show, so I’ll take the filmed version. While the “talky” section of Dracula is not nearly as effective as the earlier scenes at Dracula’s Castle, it is still effective.

As someone who has become rather well steeped in a wide variety of movies from the same period as Dracula I can tell you it is consistent in many regards with the films of that time. The exception being the entirely original mood and subject matter that makes it unlike any other movie of the immediate period, a contradiction which makes it special by comparison.

On a personal level I came to Dracula as a small boy when it aired on television. It is the first movie of this time period I can recall. It is probably only rivaled in my memories by King Kong, which came along a couple of years later on their original timeline. 1933 production standards had far eclipsed those of 1931, though my memories set these two films as equal entities each personally discovered sometime in the late 1970s. I didn’t distinguish one from the other beyond knowing that I’d get to see Dracula at Halloween and King Kong at Thanksgiving. Dracula was scary and King Kong was fun. Those simple notions still stick.

Each has had the same lasting impression. Dracula has never suffered in my mind as stagey or in any way lacking in comparison to the source material because when I first absorbed it, it was the source material.

These personal reminiscences do make Dracula a tough sell to those who didn’t come to it quite early enough.

It is very hard to praise Dracula to the unconvinced without qualifying it at every step either against its own bygone era or via personal memories, but perhaps the best evidence I can offer in its defense is that I am far from alone in according it a special place. It also speaks volumes that the film itself has continued to be beloved multiple generations removed from that bygone era.

There are many better movies you can’t say that about.

Sources

- Skal, David J. The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror

. New York: Norton, 1993.

- Weaver, Tom, Michael Brunas and John Brunas. Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931-1946

. 2nd ed. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007.

[phpbaysidebar title=”eBay Shopping” keywords=”Bela Lugosi” num=”5″ siteid=”1″ category=”45100″ sort=”EndTimeSoonest” minprice=”99″ maxprice=”699″ id=”2″]

Can’t believe I have NEVER seen this movie! (Insert head smack.) I really liked this well-written review.

Oh, there are still plenty of major ones I haven’t seen that I’m sure would blow your mind too (It’s too much fun seeking out the little ones!). That said, this makes me glad I removed the section blaming the parents of anyone who hadn’t seen this one 😉

Unfortunately, I think this is the only big one TCM isn’t airing this month … though I do think I saw it on Netflix Instant.

Thanks for the compliment, glad you liked it!