Through the Doorway

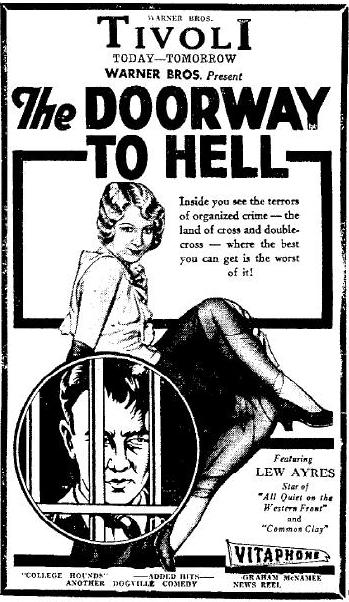

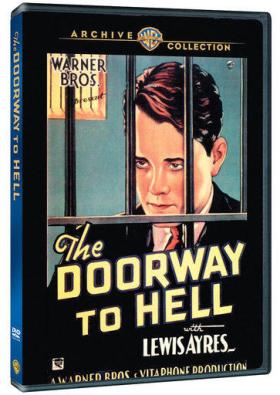

Little Caesar came to theaters in January 1931 and The Public Enemy followed that April. But before either and coming courtesy of the same studio, Warner Brothers, The Doorway to Hell made a huge hit with theatergoers in October 1930.

Little Caesar came to theaters in January 1931 and The Public Enemy followed that April. But before either and coming courtesy of the same studio, Warner Brothers, The Doorway to Hell made a huge hit with theatergoers in October 1930.

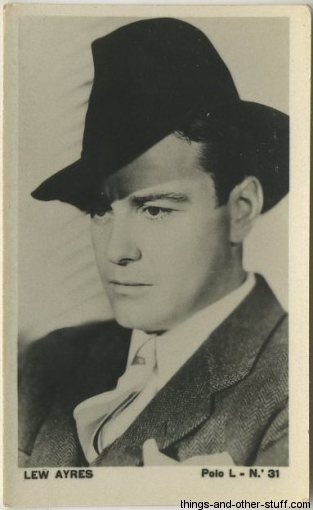

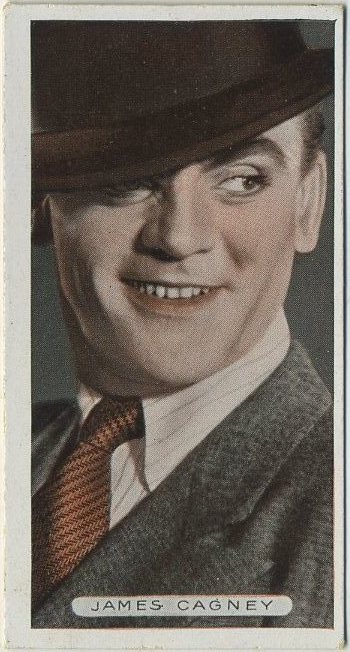

The Doorway to Hell is no static early talkie. It is driven by action punctuated by violence as well as dynamic acting from a cast of mostly unfamiliar faces though headed by a breakout 21-year-old star in Lew Ayres. A face then unfamiliar would have been that of James Cagney who gives us a big taste of what was to come in only his second film appearance.

Directed by Archie Mayo, already long with Warner Brothers and with exciting future releases such as The Life of Jimmy Dolan (1932), The Mayor of Hell (1933), Bordertown (1935) and The Petrified Forest (1936) awaiting him at the same studio, The Doorway to Hell was an early example of producer Darryl F. Zanuck’s trademark ripped from the headlines stories animated by the modern slangy dialogue that would soon be seen as a staple of Warner Brothers films. And like many that would follow, this baby moves!

Biographer George F. Custen

Biographer George F. Custen wrote about Zanuck’s early struggles to make a living off his writing and noted his first financial score actually came in writing ad copy for a hair restorative product being hawked by patent medicine huckster A.F. Foster (48). Foster later followed the money and went into the bootlegging line, an entrepreneurial endeavor which ended with his murder. Custon wrote that a stunned Zanuck then took a major interest in crime and according to a 1934 New Yorker article that he cites became obsessed with contemporary Chicago literature and history (133).

The Doorway to Hell soon followed as the first entry in the Warner’s gangster cycle. It would be a popular money-maker but history soon usurped its standing with those explosive twin follow-up hits early in 1931. Little Caesar and The Public Enemy no doubt perfect the effort put behind The Doorway to Hell and probably the only negative side effect that their towering stature has had is in leaving The Doorway to Hell completely in the dust, practically forgotten.

The Doorway to Hell was based on an unpublished story by Rowland Brown titled “A Handful of Clouds.” While the title was dropped the phrase was used a couple of times in The Doorway to Hell. Despite its seemingly obvious connotation today, it’s explained inside the movie after Cagney’s character utters it as a threat. “I mean the kind that comes out of a 38 automatic,” he explains to a puzzled gangster. Brown’s original story would receive Doorway’s only Oscar nomination but it lost out to the John Monk Saunders based thriller The Dawn Patrol (1930).

The Doorway to Hell was based on an unpublished story by Rowland Brown titled “A Handful of Clouds.” While the title was dropped the phrase was used a couple of times in The Doorway to Hell. Despite its seemingly obvious connotation today, it’s explained inside the movie after Cagney’s character utters it as a threat. “I mean the kind that comes out of a 38 automatic,” he explains to a puzzled gangster. Brown’s original story would receive Doorway’s only Oscar nomination but it lost out to the John Monk Saunders based thriller The Dawn Patrol (1930).

Despite its original acclaim and, more importantly today, Cagney’s presence The Doorway to Hell somehow escaped modern video release. It would have been a natural in one of the Warner Brothers boxed sets of Gangster Films released a few years back, but it never made the cut. This has been remedied as of March 2012 with the Warner Archives release of The Doorway to Hell as a Made to Order DVD. Perhaps now that it is widely available

to everyone The Doorway to Hell can begin to reclaim its audience and at least carve out a better remembered place as an important precursor to the major gangster hits soon to follow.

Passing Through the Doorway

Out of the black a newspaper printing press rattles off copies which serve as the backdrop for our opening credits. Ripped from the headlines indeed! These are your headlines, 1930. Zanuck and company are just breathing life into your newspapers and getting ready to introduce you to the real Monks, Midgets and Gimpys of the streets. Newspapers will play an important role throughout The Doorway to Hell, whether they are to silently offer a transition in between scenes or be used to horrify our murderous characters with the body counts resulting from their misdeeds.

That body count is high and even if some of that carnage is only reported on screen by the newspapers other killings are shown meticulously planned and executed. While not so startling today there are a few hits that I am sure played more original in 1930. There is also one scene of outright total chaos involving rival mobs rioting in the streets with machine gun fire coming from overhead and causing fiery explosions in the middle of the brawling crowd. This scene only comes to an end as a fleet of motorcycle cops arrive at the scene, sirens blaring.

While we see Cagney as soon as the opening scene of The Doorway to Hell it’s only to whisper some instructions to young Dwight Frye, pre-Dracula, here playing hitman Monk. The scene takes place in a smoky pool hall filled to the brim with a collection of shady looking characters. Monk leaves the table to retrieve his violin case, which everyone knows contains no musical instrument, and when a crony asks him what he’s up to Monk says, “I’m going out to teach a guy a lesson.”

The guy is Whitey Eckhart (John Kelly), who is lounging on the couch while his girl, Jane (Collette Merton), gets her fortune read by a friend (Marie Astaire). When a horn honks outside Whitey tells Jane to see who it is and Jane has a brief and pleasant conversation with Monk, who remains in the car and asks her to fetch Whitey. As Jane scampers up the steps of her building Monk pulls out the violin case and begins piecing his machine gun together. Whitey peels himself off the couch and heads out leaving Jane’s friend to ask her if Whitey had double-crossed anyone lately–the cards “read awful funny.”

Whitey no more than greets Monk before realizing what’s about to happen. Begging for mercy three or four shots scream and Whitey tumbles down the front steps as Monk and the boys ride off into the clear.

Instead of digging too deep into the overall story I’d rather concentrate on three of the main characters: Lew Ayres as Louie Ricarno; James Cagney as his number two, Mileaway; and forgotten Dorothy Matthews as Louie’s wife, Doris.

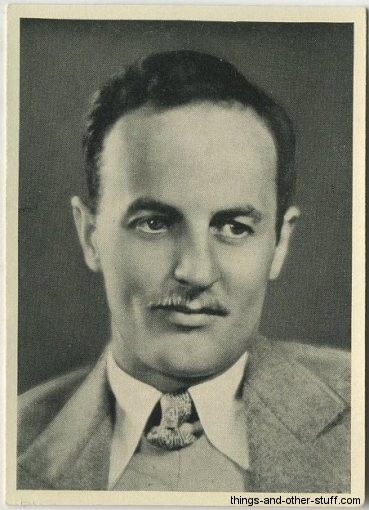

Lew Ayres as Louie Ricarno

Lew Ayres won’t turn twenty-two until a couple of months after The Doorway to Hell is released. He looks every bit as baby-faced as that statement of fact would imply. And he’s riding ridiculously high at the moment.

The teenager had scored a break in landing a couple of small parts at Pathe Studios where he managed to be noticed by outgoing executive Paul Bern, who’d soon be boy wonder Irving Thalberg’s closest associate at MGM. Through Bern Ayres would be cast in MGM’s final all-silent film, The Kiss (1929), where he played young love interest to Greta Garbo. Quite the break! An even bigger one followed when his performance in The Kiss led to a test and eventually the leading role in the Oscar winning classic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Ayres was immediately one of the hottest properties in Hollywood. With All Quiet’s incredible success Universal put Ayres under contract and the loaned him out: first to Fox for Common Clay (1930) opposite Constance Bennett, next to Warner Brothers as the lead in our movie, The Doorway to Hell.

The teenager had scored a break in landing a couple of small parts at Pathe Studios where he managed to be noticed by outgoing executive Paul Bern, who’d soon be boy wonder Irving Thalberg’s closest associate at MGM. Through Bern Ayres would be cast in MGM’s final all-silent film, The Kiss (1929), where he played young love interest to Greta Garbo. Quite the break! An even bigger one followed when his performance in The Kiss led to a test and eventually the leading role in the Oscar winning classic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Ayres was immediately one of the hottest properties in Hollywood. With All Quiet’s incredible success Universal put Ayres under contract and the loaned him out: first to Fox for Common Clay (1930) opposite Constance Bennett, next to Warner Brothers as the lead in our movie, The Doorway to Hell.

After the Whitey Eckhart hit, a newspaper headline blares: “Police Search for Louie Ricarno: Napoleon of Underworld Sought for Questioning of Whitey Eckhart Murder”

Robert Elliott is Pat O’Grady, the police Captain on the case who has a long, but never revealed, history with Louie. Elliott is humorless as O’Grady though somehow manages to hint at some warmth while delivering lines with as little emotion as he can muster. O’Grady isn’t the typical cheery Irish cop of the screen by any stretch, he’s the hardened veteran who’s seen so much it has drained his voice right down to a monotone. He has his men looking out for Louie when a call buzzes in announcing the arrival of, who else, the highly sought kingpin, Louie Ricarno.

“Well, here I am with all the answers,” says Ayres as Louie Ricarno, strutting into police headquarters like he owns the place. Ayres threatens to come off as a bit too smarmy in this initial scene, but he tones it down some to go head to head with the Captain, Pat O’Grady, who’s all over him about the hit on Whitey. Louie won’t spill and when O’Grady pushes him he spits out that “My racket is beer and you know it. I’m in a legitimate business, I am.” Ayres’ line delivery isn’t great, but he’s got a bit of a mean fire burning behind his eyes in this scene.

O’Grady for his part doesn’t despise Louie, he actually feels a bit sorry for him even saying that it’s too bad to see such a swell kid involved in this racket. Louie talks of getting out one day and writing a book about his exploits, or as he puts it, a history of his life at $3.50 a copy. O’Grady doesn’t think so, he sees a far darker end coming for Louie. “So you think the chair will be the blow-off for me?” Louie says. “I don’t think I’ll mind, sweetheart, if I can have you sitting on my lap,” he tells him. Louie laughs at O’Grady as he goes on his way, walking right out of police headquarters.

Critics find Ayres too young for the part of Louie, but I’d imagine that a baby faced killer probably should be pretty young. While we’re never told how Louie made his way into crime we’re given a good idea when we learn that his parents are dead and that he lost two siblings to a bout of typhoid caused by some bad milk delivered out a shack he wishes he burned down long ago. It’s never stated, but maybe it was through all that tragedy that Pat O’Grady first came in contact with Louie. The police Captain certainly hints about having known Louie when he was a good kid.

On showing his new bride the neighborhood he grew up in, the worldly Doris (Dorothy Mathews) comments that “Life’s cheap in a neighborhood like this.” So it is no secret how Louie found his way into a life of crime, though it is left a mystery how he managed such a fast rise at such a young age.

Equipped with not much more than a Napoleon fetish and a capable and trusted second in command in Cagney’s Mileaway, Louie soon hosts a meeting in which he organizes crime in the city with himself at the head of the syndicate. It’s at this meeting that we get a hint of the tactics which certainly aided Louie’s rise.

Louie goes nose to nose with a couple of the older men and his over-the-top threats get them to back down. When the toughest nut of the group, Rocco (Noel Madison), refuses to cave and Louie notices his henchman pointing a semi-concealed weapon at his gut, the young mobster looks like he’s beginning to waver. Wiping his brow and commenting on the heat, Louie has Mileaway open the blinds to get some air in the room and, lo and behold, two of Louie’s boys sit with machine guns aimed at the entire mob.

“How do you like it, sucker?” Louie asks, his smirk making him look a bit demented. “I ought to give you a little of that heat just for luck. Go on,” he says to Rocco’s muscle. “Put that toy away, it’s too small.”

While Rocco is surely going to be a thorn in Louie’s side there’s no doubt this antic put him over with the rest of the room. The baby faced killer leads the organization not only because he has brains but because he knows how to use fear.

James Cagney as Mileaway

Before Louie takes the town over we get to meet James Cagney as Mileaway as he goes around town making sure all of the right people come to that overheated meeting.

The Doorway to Hell is James Cagney’s second film role after Warner Brothers called him and Joan Blondell out to Hollywood for Sinners’ Holiday. It’s a fantastic warm-up for what would be his fourth film, the all-time classic gangster flick, The Public Enemy, just six months later. In The Doorway to Hell, Cagney is sixth billed, but honestly he and Dorothy Mathews, perhaps along with fifth billed Robert Elliott as the lawman O’Grady, are the most memorable actors in the film after Lew Ayres. No doubt Ayres is the star, but a case can be made for Cagney enjoying the second most important role in The Doorway to Hell.

The Doorway to Hell is James Cagney’s second film role after Warner Brothers called him and Joan Blondell out to Hollywood for Sinners’ Holiday. It’s a fantastic warm-up for what would be his fourth film, the all-time classic gangster flick, The Public Enemy, just six months later. In The Doorway to Hell, Cagney is sixth billed, but honestly he and Dorothy Mathews, perhaps along with fifth billed Robert Elliott as the lawman O’Grady, are the most memorable actors in the film after Lew Ayres. No doubt Ayres is the star, but a case can be made for Cagney enjoying the second most important role in The Doorway to Hell.

Just to show how little the actual billing matters in this one, Charles Judels is second-billed as Marconi the florist and had all of his scenes cut. He’s not in the movie at all. The closest he comes is when Ayres tries to phone him but the line is busy.

While Mileaway is not nearly the psycho that Tom Powers of The Public Enemy will be, Cagney already shows in The Doorway to Hell that he can manage to be a charming as hell killer. My favorite bit of Cagney comes when Louie sends him out to tell each of the local mobsters that they had better show up for that big meeting. Everyone Mileaway visits knows what’s coming, that Louie plans to take over, and each of them is hesitant about going. Mileaway makes his point to attend with typical Cagney flourishes at each stop.

First Cagney visits Midget (Edwin Argus) on his turf at the Acme Brewing Company. A little banter involving Mileaway strongly suggesting Midget make tonight’s meeting comes to an end as Cagney says, “I’ll see you there sweetheart,” while pulling a cigar out of Midget’s breast pocket. Before Midget can protest, Cagney waves the cigar under his nose and then replaces the cheap cigar to Midget’s pocket looking as though he’d just tortured his nostrils with something especially rancid.

Next Mileaway stops by Hymie’s (Eddie Moran) to assure the reluctant and somewhat meek mobster that he’s okay with the meeting Louie has called. It’s just business, Cagney tells Hymie with two gentle pats of the cheek. Hymie asks “What kind of business?” and Mileaway replies, “A certain business,” in a good-humored tone while deftly reaching up to Hymie’s shoulders, taking hold of his suspenders and casually tugging them down to his waist before walking away.

This business with Hymie’s suspenders, just like the cigar trick with Midget, comes so fast that it’s almost like sleight of hand!

Finally Mileaway has to pay a visit to the toughest customer of the bunch, Rocco (Noel Madison), who doesn’t want to be told anything by anybody. He’s a hard guy. Cagney finally resorts to a threat saying, “Something’s liable to happen if you don’t show up.” Rocco coolly replies, “Something’s liable to happen if I do show up.”

Noel Madison as Rocco at the left. I'd love to know who the actor is to the right of him because he might be the scariest SOB in the entire movie!

Mileaway informs Rocco, as he has the others, not to carry any weapons to the meeting. Rocco says he doesn’t need weapons, he has friends. Pausing a moment Mileaway finally asks, “Wasn’t that a lovely funeral they gave Whitey Eckhart the other day?” hearkening back to the opening scene outside the apartment building. “All his friends were there. If you know what I mean,” finishes Mileaway, waving his hand in an expression I use myself to describe something as so-so.

The funny part of that last line Cagney delivers is that we don’t actually her him speak the word mean at the end of that sentence. The line is “All his friends were there. If you know what I m–” and then we cut to the next scene while Cagney’s hand only begins to waver in the air. It’s like after that 1-2-3 punch of what we’d soon think of as classic Cagney showmanship Mayo and Zanuck decided, C’mon, we don’t need to do this guy any favors to put him over.

No sir, James Cagney has arrived. After having finally seen The Doorway to Hell I’m left thinking William Wellman is much less the genius than I had believed for having the idea of swapping Cagney and Edward Woods’ roles in The Public Enemy. After Doorway it was obvious.

By the same token I’m glad Cagney and Lew Ayres didn’t swap parts in The Doorway to Hell. Oh, I have no doubt Cagney would have hit it out of the park as Louie, but Lew Ayres is more than serviceable in the part. Ayres is especially good when the hard facts of his gangster life come back to crush his spirits and leave him every bit as far in doldrums as he had been in All Quiet on the Western Front. I don’t know if Cagney could have managed those scenes as well as Ayres, whose youthfulness aids him in pulling off a good deal of sympathy with those masterful hangdog expressions of his.

Dorothy Mathews as Doris

Dorothy Mathews plays Doris, Louie’s girlfriend and quickly his wife in The Doorway to Hell. She’s a pretty blonde though a bump in the middle of what’s a bit of a pretty long and sharp nose stops me from calling her a great beauty. Ayres might be too pretty for her. Cagney is just right. But even if you don’t find Mathews to be a looker, she’s more than feminine enough to be an object of desire for the boys. The more she talked, the more I liked her. Reminded me a bit of a poor man’s Virginia Bruce.

Born in New York, 1912, Miss Mathews had a small part in A Girl in Every Port with Victor McLaglen, disappearing long before Louise Brooks takes things over (I think Mathews is the girl that gets in between McLaglen and Robert Armstrong’s first meeting, but I’m not positive), and later played in The Widow from Chicago for First National, then controlled by Warner Brothers. Her screen career only consisted of a few bit appearances and from what I can tell her Doris in The Doorway to Hell would be her biggest role. It seems a bit odd, but she is listed as having appeared in Millie’s Daughter for Columbia in 1947, her final screen appearance and first since 1935 if that information is correct.

Dorothy Mathews and husband Donald Davis pictured on a 1952 press photo published in the Baytown Sun of Baytown TX, April 10, 1952

She and Davis continued to be involved in show business, specifically producing a few episodes of various anthology television series, including Studio One, for CBS in the early 1950’s. The original caption on the photo picturing the couple together here said that they even won a Peabody Award in 1949. Dorothy Mathews died in Los Angeles in 1977.

As you can tell the Dorothy Mathews biography is a bit shaky. She impressed me in The Doorway to Hell and I’m left to wonder what her unique circumstances were in not getting the break that should have followed (Perhaps she opted out after marrying. I didn’t discover the info putting a 1932 date to her marriage until after completing this piece). She obviously wanted to act. The later Ethan Frome clipping proves that. In The Doorway to Hell she has a plum part and handles it well enough that I’d expect to find more strong work from her in the future. Not so.

Her Doris comes from the same gutter that Louie and Mileaway develop out of and in playing her Mathews comes across as naturally good-natured and subtly seductive. I thought one of the weaknesses of Doorway was in not completing her character’s story. I became quite attached to Doris, but she’s just dropped in favor of the boys after awhile and we never learn what becomes of her.

The love triangle between Louie, Doris, and Mileaway is more complicated than you’d expect in a story like this. Louie is never made aware that Doris is two-timing him with Mileaway and he’s dedicated to the both of them right until the end. Doris seems to use Mileaway for general kicks while there’s never any reason, beyond the physical relationship with Mileaway, to doubt that deep down she loves Louie. Doris doesn’t come off as cheap. Her relationship with Mileaway isn’t so much tawdry as just something that happened and continues to happen.

By the time Doris meets Louie’s kid brother, Jackie (Leon Janney), at the military academy we already know she has something on the sly with Mileaway. Yet she’s beaming in that scene and seems very taken with young Jackie who plants a big kiss on her after hearing that she has married his brother. Later on in Florida, despite a phone conversation with Mileaway where she tells him how much Louie has begun to bore her, “I feel like I married an ex-champion or something,” she says, there remains a genuine warmth between the married pair of Doris and Louie.

By the time Doris meets Louie’s kid brother, Jackie (Leon Janney), at the military academy we already know she has something on the sly with Mileaway. Yet she’s beaming in that scene and seems very taken with young Jackie who plants a big kiss on her after hearing that she has married his brother. Later on in Florida, despite a phone conversation with Mileaway where she tells him how much Louie has begun to bore her, “I feel like I married an ex-champion or something,” she says, there remains a genuine warmth between the married pair of Doris and Louie.

There’s a scene where Louie believes he’s come to the end of the book he’s writing when he asks Doris what that Latin word is that comes at the end of books. Doris, casually sunk into a big chair a few feet away looks puzzled for a moment before it occurs to her to flip to the back of the book she has on her lap. “Finis,” she says, smiling and looking as proud of herself for thinking of a solution as she is of Louie for finishing the book. It’s just a little moment of domesticity in The Doorway the Hell, one actually leading to a much bigger moment, but the couple looks so settled together that it’s almost quaint. Somehow it impressed me as one of my favorite scenes.

Louie completely trusts both Doris and Mileaway and when he makes his return to his former territory he even sends the pair out on a date so he can take care of some personal business. We next see Mileaway and Doris in the back of a cab, Doris leaning comfortably into him as they decide where they should go that night. “I could think of a thousand places if you weren’t married to Louie,” Mileaway says to her. The line seems to be as much about loyalty as it is fear. Doris pauses a moment, raises her hand to her mouth and casually wets the area around her wedding ring before sliding it off her finger and placing it in Mileaway’s hand. “Now, where do you want to go,” she practically purrs. It’s a very sexy scene!

Reign of Terror, Napoleon, Exile

Louie Ricarno quit the mob and once the chaos that grows out of that gets personal he finds himself pulled back in. As Louie exacts his cold-blooded vengeance both Mileaway and Doris are pushed aside and the police chief, O’Grady, begins to play a bigger role. It’s O’Grady along with a portrait of Napoleon in Exile who play out Louie’s final scene with him.

While that portrait is a bit too convenient the Napoleon legacy pervades throughout The Doorway to Hell.

When Doris asks Louie why he wants to send Jackie to military school and turn him into a soldier, Louie drifts off into his own world and says, “Because war is a grand racket. You know, I was just thinking. If I was born a couple of hundred years ago I might have been a big as man as Napoleon.” He practically swoons at the idea as an amused Doris looks up to Mileaway, who slowly tucks his hand over his gut and inside his shirt as the historical figure was known to do (oh, that Cagney!).

Louie later goes off on the same topic with the head of Jackie’s academy (Kenneth Thomson) who stuns Louie with his reply that war is “cruel and profitless” and that they’re much more concerned with making the boys “good citizens.” Louie looks concerned, perhaps a bit puzzled by this idea, but he soon follows through on his plans of retirement.

When Louie comes back North the headlines scream “Reign of Terror.” Sure, the history is a bit backwards but it still makes for a nice play with the Napoleon element already in place. “Return from Exile” would have been more appropriate to our story but Louie’s grand return did feature more senseless violence rather than his earlier calculated plays at power.

The result of Louie’s reign of terror is a second exile. This time not of his own choosing.

A Hit!

While The Doorway to Hell delivers a satisfying pay-off it falls far short of the memorable last shots of Edward G. Robinson in Little Caesar or Cagney in The Public Enemy that I easily recall to mind simply in typing out this sentence. I wouldn’t call the final moments of The Doorway to Hell inconclusive by any stretch, but it lacks the definitive endings given to Robinson and Cagney in those classics which followed.

It was a hell of template to kick off a cycle with though and it was still paying off for the studio as those other films were released.

The November 1, 1930 edition of Motion Picture News trumpeted that “the big noise in theatre circles was the $23,000 piled up by The Doorway to Hell at the Stanley.” The same publication a week later reported “record-breaking business at the Embassy in San Francisco, the Palace in Toledo, the Lyric in Indianapolis, the Earle in Washington, the Stanley in Philadelphia, the Downtown in Los Angeles and the Stanley in Pittsburgh!” By the November 22 edition noted that the movie was “continuing its sensational run at the Strand. The film, now in its third week, has ridden high over the business slump to chalk up a record for the house. Getting $41,322 in its second week, the film proved a real surprise and its unheralded strength created plenty of talk.”

By the same token the same publication reported it flopped in Minneapolis where Whoopee with Eddie Cantor and the Amos and Andy title Check and Double Check did the big business instead. Likewise in Detroit where the Amos and Andy picture was cited again as was documentary, Africa Speaks! It would seem these areas had a better taste for comedy than the action packed urban gangster story.

The New York Times called The Doorway to Hell “an intelligent and exciting motion picture of Chicago gangland.” The Times sees through Doorway’s chaos to observe that “The film has humor, but it is a humor growing almost always out of a grim irony.” While noting that Lew Ayres may seem a bit young for the part The Times goes out of its way to praise him as well as call special attention to Robert Elliott as Captain O’Grady. Of Louie’s relationship with Doris they capture the spirit of the movie in reporting that “The story has its romance, but it is plausible and cruel like the rest of the film.”

The Doorway to Hell is innovative and influential. Anybody who revels in the big three classic gangster movies, and that includes the slightly later Scarface (1932), and certainly anyone who has purchased those boxed sets I referenced earlier, has to own The Doorway to Hell. Head to Warner Archives now.

Judge Lew Ayres for yourself, I like him, but I can understand the criticism of those who don’t. Ignore the references to Cagney having a small role. It’s not. Arguably only Ayres has more to do than Cagney here. Ignore the 1930 release date, The Doorway to Hell plays like a film from 1932 or ’33, and if you watch a lot of movies from this period you’ll know exactly what I mean.

The Doorway to Hell was a hit. Now it’s an often forgotten template for those great gangster movies soon to follow. It should be more. More than a curiosity, The Doorway to Hell deserves to recapture some of that popularity it had back before audiences knew anything better was on the way.

Highest recommendation for anyone who likes gangster movies and especially to Cagney fans for whom The Doorway to Hell is a must.

Sources:

- Ankerich, Michael. Broken Silence: Conversations with 23 Silent Film Stars

. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1993.

- Butterfield, C.E. “Red Caposella To Broadcast Kentucky Derby; Clem McCarthy to Be Missing.” The Bee (Danville, VA) 14 April 1952: 20.

- Custen, George F. Twentieth Century’s Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck And The Culture Of Hollywood

. New York: BasicBooks, 1997.

- “Walter Hampden to De Starred in Ethan Frome at Des Moines.” Ames Daily Tribune-Times. 24 March 1938: 9.

[phpbay]James Cagney|Lew Ayres|Dwight Frye, 12, “”, “”, “”, “”, 39[/phpbay]

Loved your post, Cliff — and I love Doorway to Hell. In fact, while I often read blog posts that make me want to see or re-watch a film, yours here is the first one that literally made me get up and find my copy. It’s on right now! I thought Lew Ayres was great in his role — fearsome and appealing at the same time — of course, Cagney was outstanding, and I remember being really shocked by the violence in the film the first time I saw it. I enjoyed reading about the info you provided about Doris Mathews, and will be giving her a closer look as I watch the film again now. Really enjoyed your post. Back to the movie! 😮 )

@0e7459ee9cf9233de5ae1ece96537cf9:disqus I’ve been working the past 12 hours or so putting together all of these notes and collecting my thoughts into the writing that appears above (doorway to hell, indeed!) and your comment just gave me instant gratification that it was all worth while–THANK YOU!

I couldn’t believe what a finished product Cagney was, it’s all there. Those three quick scenes I described, which all come back to back, simply perfect!

Do let me know what you think of Dorothy Mathews, I thought she had a very subtle appeal. Heck, maybe she was supposed to be something else and blew the part, but what I got out of her was clean and natural, really enjoyed her.

Outstanding article, Cliff — “Doorway to Hell” is a favorite of mine, but I don’t have a copy! Like Karen, I would pull mine out right away to watch it — so frustrating, and it’s all your fault! LOL! I loved Lew Ayres in the part — he had that sweet baby face, and that always works for me when such an actor plays the bad guy. I had only seen him in the Doctor Kildare movies before I saw Doorway, and he did great. Cagney, of course, is always a treat to see. You are so right — seems like Cagney was the whole package right from the start of his career. Your background info and insights were so well done, and I really enjoyed this!

Thanks Becky! I’m still stunned at how hard this one was to find until just last month when Warner Archive released it! Ayres is so young he makes a 31-year-old Cagney seem like an old-timer!

Cliff, Thanks for your wonderful review; I really enjoyed reading it.

I agree with you that this is a movie that any serious fan of gangster films fan should see. It’s not on the level of the all-time greats like The Public Enemy and The Roaring Twenties, but it’s the best of all the “non-famous” (ie. I’d never heard of it until I saw it playing on TCM a few days ago) 30’s gangster films I’ve seen.

There’s nothing as great as enjoying a movie that you enjoy and then reading a review about it that you enjoy; great to know there are other serious fans of the 30’s WB gangster cycle that like this stuff, and that it isn’t forgotten.

Thanks again!

Hi Steven,

So glad you enjoyed The Doorway to Hell and also my coverage of it. Thank you!

I agree, it’s not as good as the better-known classics, but I think it’s an important movie in the development of the genre. Having Cagney in it is like a cherry on top!

Wellman said he swapped Cagney into the starring role of The Public Enemy after seeing what the kid could do. I wonder if Doorway would be a classic if director Archie Mayo made that move with Cagney/Ayres.

Though I like Ayres in the part myself (psycho babyface in a gangster flick, works for me!) he seems to be the main problem for detractors.

Doorway released in October 1930, followed by Little Caesar in January 1931 and The Public Enemy in April of 1931. Watch them consecutively and you can really see the genre grow up as well as witness the general advancement of early talkies.

Thanks again,

Cliff

I agree with you about Ayres, I liked him. Yes, he’s young; but it wouldn’t make sense for the cop to give him the speech in the beginning otherwise. The cop sees a kid who is making bad decisions, and wants to save him. If he was 35 or 40 years old, no way would the cop be giving him that speech. I like the idea of a kid who goes from rags-to-riches, stares down the bigger guys. So, I have no problem with Ayres. Of course, if it had Cagney in the lead, maybe it would have been considered a classic like The Public Enemy; who knows. Ayres isn’t Cagney (nor is anyone else), but Ayres did fine for himself.

There’s lots of versions of when/why the switch with Cagney was made in The Public Enemy. One version I heard is that Cagney had a supporting role in “The Millionaire” (released like a week after The Public Enemy, but must have been shot before), and he stole the film. Another version is that it was only after filming began on The Public Enemy, and they realized Cagney was so much better than Edward Woods. I don’t think we’ll ever know for certain when/why/by whom the switch was made.

RE: your statement that The Doorway to Hell was the first in the WB gangster cycle: what about Lights of New York (1928), the first all-talking picture

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lights_of_New_York_%281928_film%29

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0019096/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

Not sure if you’re distinguishing between “Crime” and “Gangster.” I never saw Lights of New York, but I think (though I’m not sure) I’ve heard it referred to as a gangster film, I read the plot description on wikipedia on imdb; and it definitely was made by Warner Bros. Do you still stand by your statement that it was the first of the Warners gangster cycle? (or are you specifically referring to the THIRTIES gangster cycle, thereby excluding a film from 1928?

p.s. wasn’t Edward Woods sooooo bad in The Public Enemy? and even more so for Donald Cook (who plays Cagney’s brother), especially in that scene where he throws away the keg of beer and screams “it’s beer and blood.” God, what bad actors those were. The Public Enemy was a great movie (it’s my favorite of all gangster films prior to The Godfather films) but I don’t know how in hell Wellman kept that “beer and blood” scene in, without doing a re-take or having Cook fired

Another interesting film to see, as far as the birth of the gangster genre is concerned, is Smart Money (1931). It was released a few months after The Public Enemy (July of 1931), not sure when it was shot, it’s the only film in which Edward G. Robinson and Cagney appear together. Robinson is the lead, Cagney is the big supporting role.

It’s not really a gangster film cuz it’s not about organized crime – Robinson plays a gambler, Cagney his buddy. But Robinson is the fast-talking guy, you know, it could just as easily have been a gangster film, so definitely an early “birth of the genre type of film). According to IMDB, Little Caesar was released in January ’31, The Public Enemy in April ’31, and Smart Money in July ’31. So Smart Money must have been filmed before The Public Enemy was released; I doubt Cagney would have been given that supporting role if they knew what a start he would become in The Public Enemy.

You can tell Smart Money is definitely pre-Code (or, as the nerds call it, “pre-Code enforcement” 😉 there’s an implication that Cagney and Robinson are more than just gambling partners (there’s a scene where they’re eating breakfast together in pajamas!); there’s a scene where Cagney is doing sign language to Robinson, and he mimes cunnilingus.

IMO, Smart Money is as good a film as The Doorway to Hell

Hi Steven,

Regarding Smart Money — It’s another one I’ve covered on the site: Smart Money here. I actually do a timeline on that page that includes some of what Robinson and Cagney (and Karloff) were up to that year: By what I have there Smart Money went into production 4 days before The Public Enemy opened.

(I also have a mini-biography of Evalyn Knapp and a bit on the awesome Noel Francis tucked in that post.)

By the way, you can access all of my writing about gangster movies here and, with some repetition, here. I may have to give myself a refresher on a few of those to talk intelligently with you, but you may just enjoy the posts too!

On the Cagney-switch in The Public Enemy, you’re right. There are a ton of versions. I’ve seen Wellman claim credit in those filmed interviews; pretty sure I’ve read quotes from Zanuck where he claimed credit as well.

No, I didn’t mean it came first (unless I mistakenly wrote that elsewhere). In my reply above I just meant that this specific trio (Doorway, TPE and Caesar) grouped together show how far the genre came at just one studio over the course of just 6 or 7 months. I consider each of the three a great leap from the one that preceded it and find that wildly interesting!

Yup, Woods is pretty bad and, I hate to say it, Cook isn’t too good either (he gets better in later stuff, at least!). They’ve both grown on me over time, which is good for me at least! I also used to find Fairbanks, Jr. absolutely terrible in Little Ceasar, but he didn’t bug me too much when I last watched a couple of months ago. So glad familiarity doesn’t breed contempt within movies I love!

I don’t think I’ve seen Lights of New York myself–and I also don’t know why, pretty sure it’s public domain and easily accessible online–but some of the background gets a mention in my biography of Hugh Herbert, who co-wrote dialogue (yes, the later Woo Woo man).

By the way, I’m doing a little project this month writing about a few different titles from 1931. I plotted out four movies to talk about, each from a different studio and in a different genre, and one of them is planned to be City Streets, an April 1931 release, with hopes of showing Paramount’s spin on the gangster.

Cliff

I haven’t seen Lights of New York myself.

I was just saying that in the fifth paragraph of this review, you wrote, “The Doorway to Hell soon followed as the first entry in the Warner’s gangster cycle.” But if Lights of New York is a gangster film, then The Doorway to Hell, which was released two years later, was not the first Warners’ gangster cycle films. And if what I am saying is correct, then you may wanna delete that erroneous sentence from your review 😉

Thanks for sharing those links with your previous writings; I’ll be sure to check them out soon

—-

btw, I couldn’t stand Little Caesar, and here’s why: I love Robinson, but the rest of the cast got on my nerves with their waaaaaaay over the top tough guy accents, which went way above and beyond any other movie; I wanted to tear my ears out every time anyone besides Robinson opened their mouth. That cop, that guy who took over as Robinson’s right-hand man (and probably his lover) once he became the big shot, so many others; like they were all trying to out-do each other with those awful gangster accents, way beyond any other movie, and that singlehandedly ruined the movie for me. It’s a shame, cuz otherwise it was mostly very good movie – I couldn’t stand the part with the one guy who turns yellow, how he is crying in the car, crying in his room, that was awful; also, the whole subplot with Fairbanks was annoying [but I guess he was the “moral” voice against the criminal (as well as homosexual 😉 ) life ] – otherwise, this could have been a real good movie if not for the way the dialogue is delivered; I mean, how can I enjoy a movie when anytime anyone other than Robinson starts talking, it makes me wanna kill myself?

For me, the best of the 30’s gangster films is:

The Public Enemy 10/10

The Roaring Twenties 9.5/10

Dead End 9/10

Angels with Dirty Faces 9/10

Scarface 8/10

Martin Scorsese has said that The Roaring Twenties was the last great gangster film before the advent of film noir, and I agree with him.

Best of the ’40’s is White Heat.

As you can see, I’m a Cagney man 😉 I love Robinson and Bogie as actors, but IMO the gangster roles are not their best roles; are alright as gangsters but much better in other roles. Cagney is king of the gangsters

Hi Steven,

I think I’m going to stick with that paragraph as written. Of what I know of Lights of New York it had more of an impact as the first all-talkie rather than as a specific genre film. Even if that were not the case, I don’t really see it as part of this cycle of films. In other words, it led to more talkies, not necessarily more gangster films, whereas Doorway was precursor to Caesar which linked up to Public Enemy and beyond.

Of course, all this talk has jumped Lights of New York towards the top of my viewing list; I could revise my opinion after watching.

I can’t really nitpick your ratings too much, you named all of my favorites. I’d probably bump Scarface and Angels ahead of all but The Public Enemy and, I must confess, I love Little Caesar too, though I can understand if the dialogue rubbed your ears wrong.

I’m aware of the talk around the homosexual subtext in Caesar, but it’s not something I ever recognized for myself until after reading about it. I really think it plays more that way today then it did then, when, probably because of the Great War, male bonding in general seemed more intimate, but that’s probably a separate conversation and/or lengthy post.

Another one I’d put up near the top of my list is The Racket (1928), a silent film starring Louis Wolheim and Thomas Meighan.

Absolutely agree on White Heat.

Cliff

Cliff,

There’s no doubt that Little Caesar the character is homosexual. They just couldn’t mention that explicitly – I guess that even in the pre-Code days, homosexuality could only be implied (as it is in “Smart Money,” with Robinson and Cagney eating breakfast together in pajamas 😀 )

In “Little Caesar,” Caesar is fighting the woman for the affections of the Fairbanks, Jr. character. Why would he care if his friend wants to leave the mob and go dance? Why should he be sooo hurt that his buddy wants to go live anew life with that woman. There is a (not so) hidden implication there. Caesar shows zero interest in women. Normally, one of the rewards of great wealth, for a heterosexual gangster, would be pretty dames – Muni and Cagney love them some hot dames in “Scarface” and “The Public Enemy,” but Caesar shows not the slightest interest in the opposite sex.

When he’s getting dressed, his underling, played by George E. Stone, has to tell him how good he looks – and notice how Stone jumps onto the bed, too?

And then … when it finally comes down to killing the Fairbanks character … Caesar looks at him but just can’t pull the gun. As he said, that’s what you get for “liking” a guy too much. Just swap the word “like” for “love,” and there you have it.

Little Caesar’s got no use for dames.

Hey Steven,

Great to see you back, pretty much one year to the day since we last communicated!

All of your points are valid, though I’d start up top and say that there’s plenty of doubt, perhaps not by you, but I’m still wishy-washy over the idea and I know others are as well. So doubt exists. Let me put it this way, I’ve seen the movie at least two dozen times, probably more than that and at least twice since my reply last year, but I’m not ready to concede the point.

I think that’s part of what makes it so great though, different conclusions can be drawn.

I think we’d agree that Caesar is emotionally stunted. I can remember as a kid, some of the guys, myself included, getting upset when one of the fellows chose to spend too much time with a girl and not enough with the gang. We missed having him around and we were probably jealous he could get the girl while we were busy doing the same old thing. That’s how I see Little Rico, missing his pal with an undercurrent of jealousy. Immature and self-obsessed.

I’d absolutely agree with your final line, “Little Caesar’s got no use for dames,” but don’t think the two ideas are mutually exclusive.

I’ll get back to you ASAP on the other comments you left, in the meantime I’m working on a new post that I hope you’ll like–it’s about a movie starring, you guessed it, Edward G. Robinson! I’ll tease a little by adding one of his co-stars is a fella named War Cry.

Glad to hear from you, Cliff

Hi Cliff! I stumbled onto the most recent showing of “The Doorway to Hell” midstream, just at the “Finis” scene – it was indeed a sweet little scene.

While The New York Times loved the film at the time of release, I am amazed that other critics have called the direction “stodgy”. As I watched it, I wondered that a film with such original and powerful scenes such as the kid brother being dragged out from under the offending truck from the perspective of us being under the axle ourselves as his head dragged away on the pavement away from us; your aforementioned machine gun melee in wider perspective cutting to the bloody head shot of your scary SOB in a slow eye panning death stare; and then Louie deftly scaling down a three story drainpipe in longshot like a little spider after escaping his cell. I kept thinking that this is a William Wellman film, with all of his toughness and style, then I looked it up and found ARCHIE MAYO. Interesting. Learn something new every day.

Great to see Dwight Frye as something just as frightening and unsettling as Renfield – to me HE was the scariest SOB in this one, and he was just dreangedly staring in the scene of his that I caught (came in too late for his violin case).

Lew Ayers gave a very good performance in the style of the day, and very effective and believable in that context.

Dorothy Matthews- cute with those slightly downturned 30’s eyes (Marion Davies clones?) until she turned in profile. You’re right about the nose, but after a while I got to like her selling of her unique looks and her natural acting. I guess it just wasn’t the era for personality noses like Barbara Steisand or Sarah Jessica Parker (Jennifer Grey of “Dirty Dancing” had a great schnoz but got it “fixed” and thus derailed her career).

Thanks for your all your positives on “The Doorway to Hell”. I wish more critics would look at a film in period style without comparing it to modern styles. It’s like dinging Turner landscapes because they look “creaky”, “stodgy” or, the worst one, “Old Fashioned” in comparison to Picasso, or Warhol. Same art, different styles, different era, all great.

I’ll definitely look to add this one to my collection!

Marilyn Small