I hadn’t thought much of Alma Rubens in the several years since publishing Tammy Stone’s biographical piece about her in the old Profiles & Premiums Newsletter. When I was digging through NewspaperArchive.com a few days ago for background information about Ricardo Cortez for my Symphony of Six Million (1932) article I was struck by a line in Wood Soanes’ October 2, 1932 piece about the Symphony star:

The manliness with which Cortez conducted himself throughout the affair with the late Alma Rubens earned him commendation in many quarters outside of Hollywood. Even before all of the facts of the case were known, this troubled young husband had the sympathy of his screen followers as much as the ill-starred wife did from those who knew her plight.

“Hollywood can be cruel to romance,” Cortez said as we discussed the dark days of his life. “I’ve been given a lot of credit that I don’t deserve.”

Alma Rubens was a major film star by age 19 in 1916 after co-starring in a couple of Douglas Fairbanks hits. She already had two husbands behind her by the time of her January 1926 marriage to Cortez and was by that time, by her own account, already a drug addict. By the time of her death, January 22, 1931, she had already separated from Cortez with papers announcing her plans to sue for divorce as late as September 1930.

Cortez later claimed that he’d had no idea of how seriously ill Alma was until just two hours before she passed. She’d been in a coma for 60 hours before her death. After her death Alma Rubens’ mother sued Photoplay Magazine for an April 1931 article she claimed was libelous for stating, among other claims, that Rubens and Cortez were already divorced. Cortez testified in June 1932, the million dollar suit was reported as settled and taken off the judicial calendar at the start of February 1933.

Alma Rubens completed her memoirs just over one month before she died. They’re available in book form today as Alma Rubens, Silent Snowbird, but I fell into them online last night as they were originally published in The San Antonio Light just a couple of months after her death. I probably would have just bought the book and waited had I realized how hard this task was going to be on my eyes! Perhaps attesting to how big a deal Rubens’ passing was it should be noted that the Light serialized all 44 chapters of what it called “Alma Rubens’ Own Story” daily between March 16 and May 7, 1944.

It’ll be impossible to forget Alma Rubens after reading her life story in her own words. I spent the better part of two hours shaking my head in disbelief as the poor woman perpetually slipped back into addiction time and time again. At one point the star who claimed to have made as much as $3,000 per week at one time was forced to put her maid to work as her supplier because Rubens had no cash on hand for dealers but the maid was willing to take her expensive clothes in return for drugs.

As I read the Alma Rubens story I initially had no idea how close she was to her own death as she wrote it. Everytime I reached the bottom of a new entry to find the message To be continued I was stunned as the timeline of Rubens’ narrative came closer and closer to the day she died.

It was only after reaching the final installment on May 7 that an Editor’s Note explained the timing of Rubens’ memoir. She completed the book one day before she left New York, December 15, 1930, to return West where she was greeted by her mother and family doctor on December 19 in Los Angeles. On January 5, 1931 she’d be arrested in San Diego on a federal charge of smuggling and possession of narcotics–specifically Rubens was nabbed with a hundred grains of morphine sewed into the lining of an evening gown found in her overnight bag.

“I’ve been framed,” Rubens claimed. “They haven’t given me a chance. I’m making a hard fight, but if the newspapers, the public and the officers won’t give me a square deal, what can I do?” While Rubens honestly and bluntly admits exactly what she is and what’s she done throughout her life story, it doesn’t take a very careful reading between the lines the see she usually managed to find someone else, whether it be doctors, pushers or even husbands, to share the blame for her addiction and constant relapses.

This January 27, 1929 headline seems to be the first public indication of Alma Rubens' troubles. Prior to that her absenses were explained as vacations and health issues. This kind of put it all out there for the public.

From jail in San Diego on January 5, 1931 she claimed “I’m not taking drugs and never shall. I’m off the hop for good. I never though I would see the day when I wouldn’t take a drink, but I didn’t today.”

This same woman concluded her autobiography on December 14, 1930 by writing, “God pity me, God forgive me, and God help all poor mortals who fall into the clutches of the monster–dope” (7 May). This was her final sentence of a long account of addiction to morphine, cocaine and heroin filled with sanitarium stays perpetually followed by relapses. In retrospect the events of January 5 were a loud announcement that nothing had changed. Despite being back West with her mother it seemed her downward spiral was all set to repeat itself.

Except Rubens caught a cold. She got sick shortly after she was released from jail on a $5,000 bond to await trial. The cold turned to pneumonia and Rubens, her body weakened by all those years of addiction, died, January 22. With the exact timeline spelled out it’s no wonder estranged spouse Cortez didn’t know until the last minute.

“Alma Rubens Own Story” is a complete biography told by Miss Rubens from the time of her birth up until those few weeks before her death. It’s opinionated and filled with memories which seem at times too vivid for somebody in Rubens’ condition. The graphic details of her sanitarium stays kept bringing to mind the later film The Snake Pit (1948). In fact, it read like source material. But her time institutionalized is told in detail that I’m not quite sure somebody as bad off as Rubens would be able to recall. Typically she’s barely functioning during this period, yet she remembers several specific incidents and conversations that always seem to find her being bullied or taken advantage of. This presumed paranoia only adds to Rubens’ shocking story.

Sadly Rubens comes close to glamorizing her highs, especially when she writes of her almost being predestined to the lifestyle years before she’d touched a narcotic: “Even then, governed as I was by that almost uncontrollable impulse to do the forbidden, the bizarre, the unusual, I could mentally transport myself into the character of a dope fiend, a huge vampire bat, and as such, in my imagination, I could flit hither and yon, making my deathly visitations at will just for the sheer thrill of feeling my own power” (20 Mar).

Rubens is hot and cold with little in between when it comes to husband Ricardo Cortez. She almost seems to glory in exposing him as the son of a New York butcher; as a Jew and not a Spaniard. She claims not to have known of Cortez’s actual heritage until after they’d been married for over a year. She also tells a specific story purporting to be how she discovered the truth. At a restaurant one night a waiter, recognizing Cortez, sat down with them and tried conversing with him in Spanish. Rubens glories in telling her readers that Cortez had no clue what he was saying. She says she needled Ricardo over this in a fun loving way but that he had no humor about it.

Newspaper photo of Ricardo Cortez with Alma Rubens (sorry about the poor quality!)

But Rubens also writes, “To do Mr. Cortez justice he never suspected that I was an addict, not for a long time, and when he did begin to suspect it, he did everything he could to help me” (4 Apr). Then later, after her release from an Institution and meeting up with Cortez in New York she realizes that their marriage is all but over. “Poor Ric–I don’t wonder he lost patience with me … At first I used to cry about him, but gradually his image faded–until I would scarcely have known him had we met in the street” (4 May).

Towards the end of her life Alma Rubens is trying her hardest to get clean with hopes of taking a part she claims to have been offered in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Problem is she cannot remember her lines. The last few chapter entries obsess over cleaning up, remembering her lines, doing Lady Chatterley, but then she writes “At the last instant of my endurance I took a sniff of cocaine, or a shot of morphine, but these doses were as weak as I could make them” (5 May). The line is somewhat shocking as immediately after she continues to talk about how she’s worked so hard to have gotten herself clean. Then there’s a knock at her door and she’s moments from another relapse.

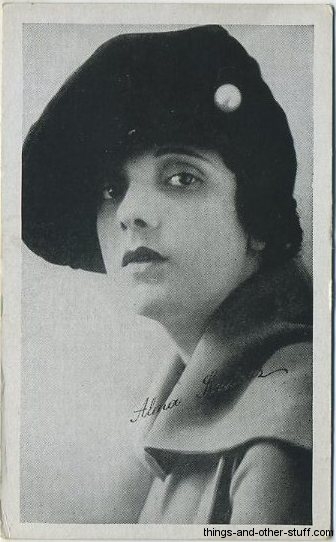

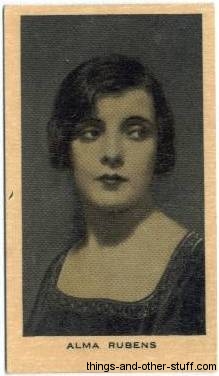

The San Antonio Light published two photos of Alma Rubens when they announced the coming publication of “Alma Rubens’ Own Story.” The Light’s editors stressed that you could not look at one photo without taking in the other. The first photo was of Rubens in the early 1920’s, at the height of her career, before any problems. The second photo was from weeks before her death and the woman pictured was far from glamorous. In fact, I focused on the later photo first and it didn’t immediately click that it was Alma Rubens.

In her final chapter Alma Rubens wrote, “That’s all I wanted–death, cool, restful death, and oblivion. I would leave behind me my poor, feeble attempt at the story of my life” (7 May). Let’s hope she found what she wanted.

Sources:

- “Former Film Star Held on Narcotics Charges.” The Billings Gazette 5 Jan 1931: 9.

- Rubens, Alma. “Alma Rubens Own Story.” The San Antonio Light 20 Mar 1931: 21.

- Soanes, Wood. “Ricardo Cortez Utilizes Wall Street Training With Talent for Films.” Oakland Tribute 2 Oct 1932: 18.

[phpbaysidebar title=”Alma Rubens on eBay” keywords=”Alma Rubens” num=”5″ siteid=”1″ category=”45100″ sort=”EndTimeSoonest” minprice=”29″ maxprice=”599″ id=”2″]

Wow – what a harrowing story. Thanks for posting.

Thanks. Yes, depressing stuff … but I couldn’t stop reading.

I loved every sentence that you wrote!

It is a shame that they couldn’t make a go of it…They were the both of them two

good people…And maybe they should have been honest with one another..

I wonder if Cortez ever talked about her later in his life. I haven’t gone looking for that info, so I wonder if it’s out there.