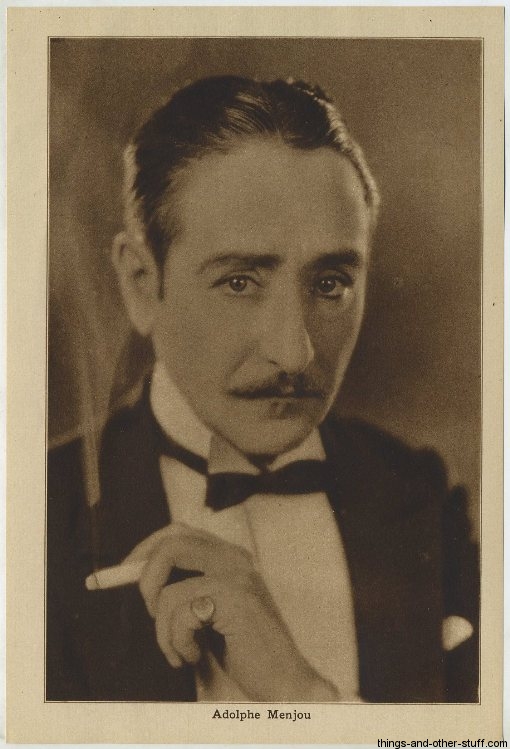

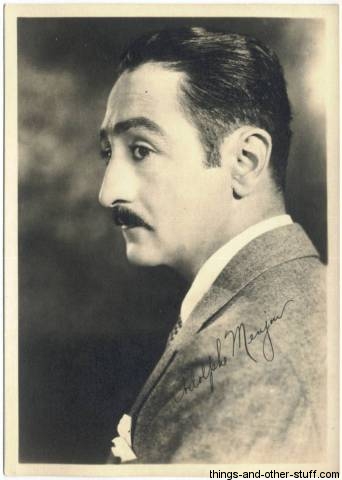

I love connecting the dots. When I began building those Hub Pages I keep pushing on you one of the things I realized as a benefit to myself was that I’d have an easy way to peek and see who needed more coverage here on Immortal Ephemera. I immediately noticed that Adolphe Menjou’s Hub was light and so I got to work on a light post eventually titled Adolphe Menjou’s Mustache … and Legacy. Putting that post together led me to Menjou’s own 1948 auto-biography, It Took Nine Tailors, a book I would not have even realized existed if I didn’t keep connecting those dots from the start.

I had reservations ordering It Took Nine Tailors. I had brushed upon Menjou’s politics in the Mustache/Legacy post and given the 1948 date I was really nervous that I’d be ordering a Red Scare era political treatise, which is not what I wanted no matter my opinion. I even skimped on my purchase of the long out of print title, opting for a decent hard cover copy but opting out of the extra dollars a dust jacket would have cost me. I expected the 63 year old book to be stale at best. Wrong.

It Took Nine Tailors is a brisk 238 page story told in Menjou’s own voice that recounts life from his 1890 birth in Pittsburgh through days spent working in his father’s restaurants and early travails breaking into the acting business right into detailed stories of breaking into movies and climbing the ladder to leading man.

Oh Menjou definitely colors a few of his stories, of that there’s no doubt, but unlike some of the more recently written autobiographies I’ve read it’s not a questionable tell-all and it’s star doesn’t make excuses to cover themselves at every wrong turn. Make no mistake the man telling the story is cocky, a bit full of himself in spots, but never mean-spirited and he doesn’t talk out of turn though he’s more than willing to recount a funny tale if the laughs come at his own expense. Names are dropped, but never tread upon and there isn’t even a whiff of politics of any kind. I only wish there was a follow-up volume before his death, though I think we’re lucky this interesting character waited as long as he did to pen his memoirs.

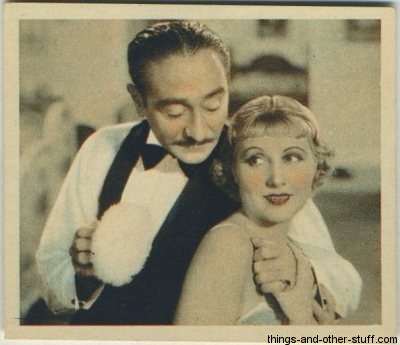

The forward was written by Menjou’s friend and sometimes golf partner Clark Gable and can be found online in its entirety. The book is crammed with photographs on slick pages, one plate every 10 or 15 pages with up to 4 images per plate. Menjou includes several still shots from films but also early family photos, pictures of himself in his developing years and candids with friends and co-workers at leisure.

It’s a quality overall package (I wish I went for one with the jacket now!) but the real good stuff inside is Menjou’s story. It Took Nine Tailors is one of those superior autobiographies where sitting down to read it feels as though you’re sitting back to listen to the writer tell you his story. And so what follows is a brief biography of Menjou highlighted by several snippets from the man himself as written in It Took Nine Tailors (page numbers follow the quotes).

Menjou, Adolphe and M.M. Musselman. It Took Nine Tailors. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1948.

Of course John Barrymore used to have an explanation for my love of the theater. “You bear a remarkable resemblance to my late uncle, John Drew,” he once told me, then added, with a Rabelaisian gleam in his eyes, “Did your mother, by any chance, ever pass through Philadelphia, my uncle’s home town?” (10).

Adolphe Menjou was born February 18, 1890 in Pittsburgh, PA. His father, Jean Adolphe Menjou, had been born in a French village called Commune D’Arbus and his mother was from the village of Letterfrach in Ireland. Menjou’s father was in the hotel and restaurant business and spent many years riding out the ups and downs of the economy through his businesses. He’d worked in New York and Chicago after arriving in the U.S. and subsequently ran his own businesses in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and eventually, back to New York, where Adolphe followed. As you might imagine he was drawn to the bright lights from there.

I was twenty-three years old when I arrived on Broadway; in my pocket was a wad of old-style, 100-cent-on-the-dollar folding money; my mustache, waxed and pointed with loving care, was as jaunty and debonair as my spirit. But Broadway gave me the cold shoulder, the bum’s rush, and a fast “NO” (34).

Menjou lived the high life until his money ran out, finally whipped after spending a few nights in a charity hotel. He returned to Cleveland where he took up a job as a traveling salesman until one day his father wrote from New York to offer him a position as assistant at his new restaurant, the Maison Menjou. According to Menjou, “the paint had hardly dried on the new sign … when I became a movie actor” (38). Menjou began picking up $5 per day as an extra in Vitagraph one and two-reelers.

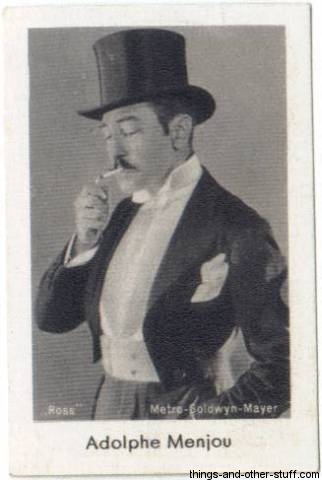

When I realized that they had me pegged as a foreign-nobleman type, I began to live the part. I bought a pair of white spats, an ascot tie, and a walking stick; and I tried to look as decadent as possible. It paid off, too. I did so many of those parts for Vitagraph that my nickname in Brooklyn was “The Duke” (39).

Menjou soon began working as an extra for Edison and Biograph as well and then spread his wings further when he realized that the Indpendents paid extras double, $10 per day, and so he soon began playing parts for World Films, IMP, Metro and other companies. After a brief whirl at vaudeville Menjou would return to work for his father once more, this time in 1915 at the Villa Menjou in Lynbrook on Long Island. It was there Menjou met the general manager of Equitable Pictures Corporation and was offered him $75 a week to work in a picture being filmed in Florida. The Florida deal fell through but Menjou used his experience and a little ingenuity to land a job with Fox, located in the same building as Equitable, at $100/week.

After a little over a year of World War I service, Menjou returned to the U.S. in 1919 and decided that the true path to riches was as a movie executive, not an actor, so he landed a job as a production manager at a $40 weekly salary. After some time of struggle Menjou decided the time had come to head west to Hollywood and go back to acting. It was tough going at first, but luckily Menjou knew a lot of people from New York, claiming Roscoe Arbuckle even lent him his Pierce Arrow a few times to let him commute to the studios. Eventually he landed a role in The Faith Healer (1921), starring Milton Sills, at $350/week.

Menjou on money in Hollywood at that time:

Those were the days when a strange new thing was happening to actors. They were becoming millionaires. Those who didn’t own their own companies drew fantastic salaries and paid their income taxes out of petty cash. Uncle Sam took less than 1 per cent out of the first $20,000; and an actor who made $5,000 a week only paid about 3 percent in taxes. No wonder the big names of Hollywood could live like Indian potentates.

Unless a person earned $1,000 a week he was a mendicant. If he didn’t have a swimming pool, three saddle horses, four servants, and an Isotta-Franchini town car, he was just a peasant. I considered myself one of the underprivileged because in my first year in Hollywood I earned only $6,500. That was more money than I’d ever made before in my life, but it was less then a week’s salary for some actors (84).

Menjou would play Louis XIII in Douglas Fairbanks’ The Three Musketeers (1921) which led to “another lucky break” after when he was cast in The Sheik (1921) starring Rudolph Valentino. After that Menjou considered himself in a bit of a slump, stuck earning $350/week and becoming typecast:

During my first few years in Hollywood I was seldom cast as anything but the villain–the no-good in the opera. I was such a deep-dyed scoundrel that the kids in the audience would start hissing as soon as I appeared on the screen–even before they knew the plot. They recognized me as a heel, a low-down, unscrupulous despoiler of women and a wrecker of homes. I was the kind of heavy who sneered at old ladies, kicked dogs, and slapped little children. I was so mean that most of the time the scenarists killed me in the last reel just to make the audience happy.

But after asking for and receiving $500 per week at Selznick for work on Rupert of Hentzau (1923), Menjou began getting better parts and more money beginning with Bella Donna (1923), Paramount’s springboard for their newest star, Pola Negri. Menjou then dedicates multiple chapters to the movie that “was a milestone in my career,” Charlie Chaplin’s dramatic reward for Edna Purviance, A Woman of Paris (1923):

We were shooting for over eight months on the picture, a period that seems fantastic today. But Chaplin’s studio overhead was small and there were no $5,000-a-week stars to be paid. I think we all finally became inspired by Chaplin’s devotion to perfection. It was not as though we were working for a salary; it was do or die for alma mater. The actors and the crew became a team trying to make the best picture it could (111).

After A Woman of Paris Menjou “was beginning to feel that I was a real somebody in Hollywood” (136). His pay was up to $1,000 per week and so:

Having been recognized by the critics as a man of the world, a sophisticate, and a connoisseur of the arts, I decided that I needed a place where I could properly entertain other men of the world … So I bought a house, spent $15,000 remodeling it, then began visiting antique shops and Persian-rug dealers. The word quickly spread around town that another sucker was on the buy (136).

Menjou would eventually sign a contract with Paramount beginning at the $1,000 per week with options for two additional years eventually boosting him to $3,000 per week. After an initial run at Paramount that he considered disappointing the 35-year-old Menjou was leery over being told he was to play the part of Betty Bronson’s father in Are Parents People? (1925). Even worse than being pushed into what he considered a character role was the director, Mal St. Clair, whom Menjou thought of as a “dog director” because of his work on the Rin-Tin-Tin pictures. Well, that all changed after they met and Menjou wound up considering St. Clair his favorite Paramount director. He was especially grateful for St. Clair’s directing him “in one of the best silent pictures I ever made, entitled The Grand Duchess and the Waiter (1926)”:

The picture boosted me up to the top rungs of the Hollywood ladder with such male stars as Rudolph Valentino, John Gilbert, John Barrymore, Tommy Meighan, William Haines, and Emil Jannings (148).

Menjou on nicknames:

I am sure I have had more nicknames than any man who ever lived. People call me “Duke,” “Menjie,” “Monjie,” and “Dolph.” In Culver I was always “Frenchie.” In Cornell I was known as “Ade” or “Ad.” During my early days in pictures my roommate Ned Hay called me “Joe.” I have a few old friends who knew me when I used my middle name, and they often call me “Jean.” But to all the members of the old Divot Diggers I am still known as “Froggy.”

Menjou discusses his career towards the end of the silent era: “… I portrayed practically the same character that had been created for me by Chaplin in A Woman of Paris. Such typing is one of Hollywood’s great faults. The studios and the producers hold desperately to formulas–not only for stories but also for actors” (179).

At the time The Jazz Singer ushered in the talkie revolution Menjou was in Paris on honeymoon with his second wife, Kathryn Carver. When everyone in Hollywood realized talkies were going to totally take over and wipe silents off the screen “I suddenly realized that I was in a very precarious position. I was a silent actor, so nobody thought I could act in talkies. The biggest Paramount stars were being replaced by stars from the stage; they knew how to talk. Tommy Meighan, who had been the highest-paid actor in the business, was finished; Gloria Swanson, the highest-paid actress, was on her way out. The studio had paid off Emil Jannings, the wonderful German actor, and he was on his way back to Germany” (191).

Menjou was in the final year of his contract making $7,500 a week when this was going on. “I knew that unless I proved I could talk before my contract expired, I would be a dead pigeon” (191). While Menjou passed his voice test he found Hollywood so distracted by the hunt for actors with stage experience that movie stars such as himself were brushed aside for a time. Menjou heard nothing from Paramount when his contract expired in May 1929 so he decided to take his wife and go on vacation in France to wait for the dust to settle some.

During the eight months I was away Hollywood had changed. The entire population consisted of ex-millionaires; the golf courses were practically empty; Rolls Royce salesmen had switched to apples; and for premieres at Grauman’s Chinese only three searchlights instead of twenty were used …

Styles were changing–had already changed. The slick, sophisticated, dress-suited characters I had been playing were out of step with the depression that was closing in on the country. They were as phoney as a plugged nickel; the public knew it and the producers knew it. I wished I had never seen a dress suit (200).

The multilingual Menjou, who had acted for the cameras during that previous Paris vacation, stayed busy by appearing in alternate language releases of Hollywood pictures in 1930. In an age before dubbing Menjou would star in both the Spanish and French language versions of Slightly Scarlet (1930), which had starred his friend Clive Brook in the main English language release. Menjou would eventually swallow his pride and offer his services to MGM at a discount. They’d give him a contract, not as a star however, but “ironically enough, I was no sooner under contract to MGM than Paramount called to offer me a job in Morocco” (201).

Menjou wasn’t satisfied with his work at MGM after returning from work on Morocco, but another big break availed itself during a chance meeting with Howard Hawks who told Menjou that Lewis Milestone was looking for him. Louis Wolheim, scheduled to star in The Front Page, had just taken ill and Milestone needed a new Walter Burns.

An odd bit of Menjou trivia: “My instructor in mathematics at University Prep was the late Louis Wolheim. He had a mind like a calculating machine and a face that looked as though it had been run over by a truck” (26). Wolheim, one of the stars of the classic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) was pegged for the lead in The Front Page, but died just a few days into production and was replaced by Adolphe Menjou! The part was huge for Menjou who would at last make his mark in the talkies with The Front Page’s success:

Professionally, The Front Page meant as much to me as A Woman of Paris. Up to that time I had made fifty-nine pictures in Hollywood; that is usually a career in this town. I had risen to stardom, hit the skids, and headed for oblivion. But as this is being written, I have made fifty-four more pictures since The Front Page and my earning power is greater than when I was a star. Hollywood has been very good to me (205).

Menjou would appear in fourteen additional films dated after It Took Nine Tailors 1948 copyright.

It was during work on one of Menjou’s favorite pictures, Little Miss Marker (1934), that he’d meet actress Verree Teasdale at a party thrown by Frank Morgan. The two were married in 1934 and would remain together for the rest of Menjou’s life.

After finishing 100 Men and a Girl I had just about run the gamut of Hollywood parts. Since then I have been entrusted with almost every type of role. In A Star Is Born I played a motion-picture producer … In Roxie Hart I was a flamboyant trial lawyer. In Bachelor Father I was a floorwalker. I have played dapper fathers, pathetic fathers, delinquent fathers.

I think I’ve finally licked the bugaboo of type casting (235).

[phpbay]adolphe menjou, 12, “45100”, “”, “”, “”, 39[/phpbay]

Thanks for this wonderful post on one of my favorite actors – politics aside, Menjou was a versatile and talented performer, w/a special flair for comedy. I enjoyed the quotes you included from his bio (especially on buying antiques: “The word quickly spread around town that another sucker was on the buy”) – he sounds like a witty man – glad you bought the bio!

Thanks much, he’s definitely a favorite here as well! I left out his funniest story because it would have taken up too much space, but basically he decided that the best investment was Gold, at the same time he didn’t trust the banks (must have been during the Depression, can’t recall). So he claims he stored all of these Gold bars in a safe located in the middle of the basement of his mansion and then a pretty good sized earthquake hit California. Fearing looters he went into a panic and starting lugging out sacks of gold to his car where he hid during the tumult! The story is hilarious as he tells it, as you can imagine in much the same voice used in the bits I included here, but it was a few pages long.