Boris Karloff: A Gentleman’s Life by Scott Allen Nollen was originally published by Midnight Marquee Press in 1999. The 2005 revised edition is currently in print and available from the Midnight Marquee website and other booksellers.

Introduction: These interviews with film book authors have fast become my favorite topic to post here at Immortal Ephemera! This time around we have the prolific Scott Allen Nollen, the authorized biographer and life-long fan of Boris Karloff as well as the author of several other film and music books published over the past thirty-plus years. You can see some of Scott’s available output on the right side of the page this interview appears on, titles including not only multiple Boris Karloff offerings but books about Frank Sinatra, Paul Robeson, Abbott and Costello, Laurel and Hardy, Louis Armstrong, Jethro Tull, Robin Hood on film, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle on film, and Warner Wiseguys: All 112 Films That Robinson, Cagney and Bogart Made for the Studio. This large body of work is all the more amazing when I take my experience with Boris Karloff: A Gentleman’s Life

into account as it’s as exhaustively researched a biography as you’re going to find on the market, not just about Karloff, but any subject!

Scott and I began our exchange of emails through, of all places, eBay. After realizing that “that’s where I’d heard that name before!” I quickly added Scott’s Boris Karloff biography, A Gentleman’s Life, to my own library of film books. I knew Karloff on screen, but after finishing A Gentleman’s Life I feel that it’s impossible to know the life of Karloff without Scott’s indispensable volume. Needless to say I was impressed, swallowed deep, and asked Scott if he wouldn’t mind answering some questions about the book and Karloff himself. Well, I think you’ll find that Scott Allen Nollen has cooperated beyond expectations, not only with his thoughtful answers about his screen hero but with the incredible trove of images he’s allowed me to put alongside his words. While Karloff led a Gentleman’s Life, I’m thrilled to say that it’s been captured in full by a Gentleman biographer, Scott Allen Nollen:

Question: Right on the front cover of A Gentleman’s Life it’s noted that this is Karloff’s authorized biography with participation of his daughter, Sara Jane Karloff. In addition your bibliography is littered with precious primary source material including letters and documents written to and by Boris Karloff. My question is how did you gain access to Ms. Karloff and what part of her father’s life did she help you best come to understand?

Scott Allen Nollen: “Gain access” makes me smile, because it was Sara Jane who tracked me down. For a lifelong Karloff admirer, that was a mind-blower right from the start!

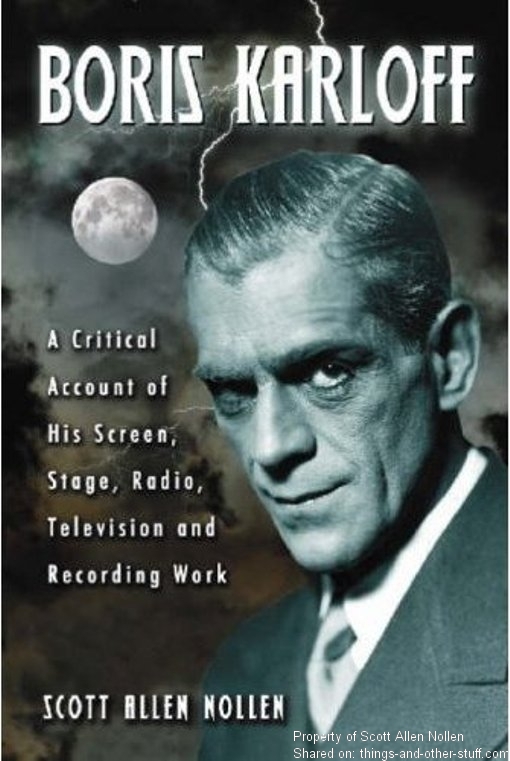

In 1991, my first book on the Anglo-Indian phenomenon born in London on November 23, 1887, as William Henry Pratt, Boris Karloff: A Critical Account of His Screen, Stage, Radio, Television and Recording Work, was published by McFarland (and is still in print, by the way). I had begun working on this book, which focuses primarily on his “terror” films (as Boris liked to call them), from the time I was in high school. During the summer of 1981, on a trip with my parents to London and various parts of England and Wales (a very generous graduation gift), I contacted Boris’ widow, Evelyn Karloff, who became my faithful correspondent and friend for the last decade of her life.

Evelyn wrote scores of letters, and she also sent me several items that belonged to Boris, including rare photos, a custom Christmas card that she and Boris sent to friends during the 1950s, and Boris’ program from the Arsenic and Old Lace stage production which he altruistically starred in to raise money for a community college theater in Anchorage, Alaska, in 1957.

Evie lived long enough to read my book (which, much to my relief, she enjoyed). After she passed away in June 1993, Boris’ daughter eventually contacted me to get acquainted and learn about my relationship with her late stepmother. In 1995, a good friend who lived in Hollywood drove me down to Rancho Mirage to meet Sara and her husband, Bill, at her home, and the idea for a second book—this time a family-authorized, in-depth biography—popped up during our visit.

My first concern was if there was enough “un-mined” primary research material to make such a book possible. After all, throughout his life, Boris deliberately obscured much of the truth about his past. He was a very private man who acted because he loved the work, not because he wanted to bask in the limelight, especially after he became a major star during the early 1930s. The ironic thing is that, during a period when sound was the new rage in films, Boris, in Frankenstein, gave a brilliant, star-making performance without uttering a single word.

Boris was one of the few actors who survived the transition from silents to talkies, because he could be such a subtle performer. He understood that understatement and nuance are the stuff of great art, not the bombast to which, unfortunately, so many performers have succumbed. “Less is more” was his approach. He rarely overacted unless he wanted to—and when he did, he usually was mocking a ludicrous script—and there were more than a few of those over the years.

During 1996, I spent weeks at a time at Sara’s homes in Rancho Mirage and at Lake Tahoe (what a lovely place to work that was!), literally being the first scholar given access to everything that still existed of Boris’ belongings, including all his documents, letters (which hadn’t been seen since they were first read by the recipients during the 1930s and ‘40s), photographs (many of them personal, and the majority never seen by the public, much less published), and even his personally annotated script he used on Broadway in The Lark, for which he was nominated for a Tony Award.

The only part of Boris’ life that Sara really recalled personally was the brief, seven-year span when she actually lived with him, the first years of her life, prior to her parents’ divorce. After Boris married Evelyn, or “Evie,” in 1946, Sara didn’t see her father very often, only during brief visits, and she enjoyed a brand-new life with her mother and stepfather, whom she really adored, in San Francisco. When Boris and Evie left their apartment at the Dakota in Manhattan (the same building in which John Lennon and Yoko Ono later lived) and moved back to England during the 1950s, Sara saw him even less. Evie liked to keep Boris all to herself as much as possible.

Sara was fantastic in putting me in touch with every possible person still living who knew and/or worked with her father, and all their wonderful memories, combined with the several steamer trunks full of the primary research materials, made for a Karloff scholar’s dream come true. The amazing thing about Boris is that no one ever made a negative remark about him: that’s why A Gentleman’s Life was the only title I ever considered for the book, and Sara concurred instantly. Working with Sara has been one of the highlights of a career now spanning 32 years, more than 40 books as an author and editor, and working with an incredible array of artists in the fields of film, music and literature.

Writing scholarly books is a poverty-generating career: One spends far more on the projects than is recouped in royalties. Book sales are now about 25% of what they were just a few years ago, so these volumes are always a labor of love and an attempt to discover the truth for people who like to read (a group dwindling rapidly). The challenge, as a trained research historian—a detective, really—is always the effort to remain as “objective” as possible (to whatever extent that is possible).

Simply put, Boris Karloff was a lovely man, a great human being, the kind who has rarely existed, and is very difficult to find as more time passes into the mists of history.

Photo Interlude – More Q&A Follow Below!

Scott Allen Nollen’s first book on William Henry Pratt, Boris Karloff: A Critical Account of His Screen, Stage, Television, Radio and Recording Work (1991), is currently available in this softcover edition from McFarland and Co. at www.mcfarlandpub.com.

Interior of the custom Christmas card sent to friends by Boris and Evelyn Karloff, designed by Mrs. Karloff’s sister, Kate Adamson, during the 1950s. [author’s collection; owned by Boris Karloff; a gift from the late Evelyn Karloff]

The original program from the 1957 amateur production of Arsenic and Old Lace staged in Anchorage, Alaska, where Karloff donated his salary to the fund for the building of a community college theater. [author’s collection; owned by Boris Karloff; a gift from the late Evelyn Karloff]

One of the research highlights of creating Boris Karloff: A Gentleman’s Life was visiting the Screen Actors Guild in Los Angeles. Here the author discusses the content of Karloff documents and photographs with Sara Jane Karloff and SAG archivist Valerie Yaros, 1996. [author’s collection]

During a “research break,” the author and his good companions took time to celebrate the 40th birthday of Ron Chaney (grandson and great-grandson of Lon Chaney Jr. and Lon Chaney Sr., respectively) at a restaurant in Rancho Mirage. Seated (left to right): Linda Chaney, Ron’s wife; William “Sparky” Sparkman, Sara Karloff’s late husband; Russ Jones, whose illustrations graced the covers of Famous Monsters of Filmland; Ron Chaney; Sara Jane Karloff; Harold N. Nollen, the author’s father; and Scott Allen Nollen, 1996. [author’s collection]

The current, revised edition of Boris Karloff: A Gentleman’s Life (2005), which includes an updated introduction and additional material concerning Boris’ role in the development of the Screen Actors Guild, is available from Midnight Marquee Press at www.midmar.com.

Question: In addition A Gentleman’s Life is jam packed with rare photographs from Karloff’s life and career with some of the early photos well worth the price of the book alone! Can you talk about any other interesting collectibles or Hollywood memorabilia that you came across that didn’t make the book?

Scott Allen Nollen: This is an easy question, requiring a very brief answer: No! It’s really all in there—even some of the priceless material Sara had on display in the (you won’t believe it) guest bathroom at the Rancho Mirage house! Even Boris’ Grammy Award was in there. One of my favorite photos shows Boris training with the U.S. Marines in 1945, prior to heading into the South Pacific to perform Arsenic and Old Lace with a group of military actors, including future Hogan’s Heroes commandant Werner Klemperer!

Karloff learns some basic combat principles with the U.S. Marines before heading into the South Pacific to perform in a military version of Arsenic and Old Lace. Standing behind Boris is Private Werner Klemperer, who played Mortimer Brewster in the 1945 production. [author’s collection; a print from the original owned by Boris Karloff]

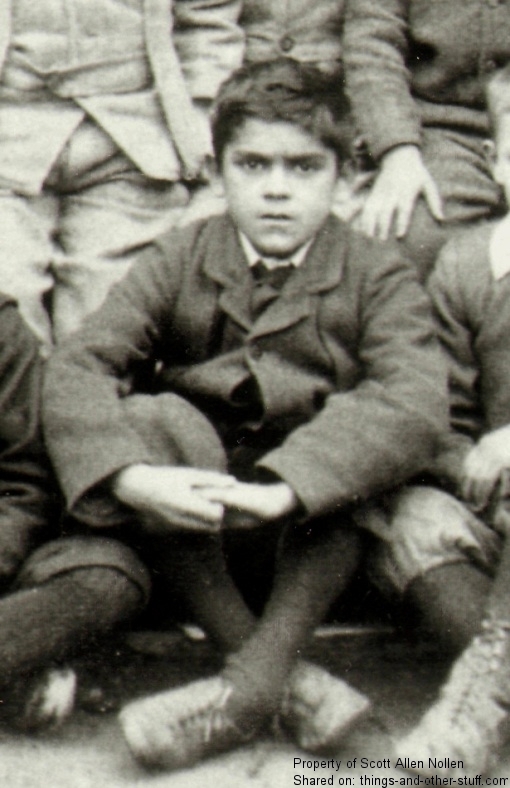

Ten-year-old “Billy” Pratt, while a student at Enfield Grammar School in 1897. [author’s collection; a print from the original at Enfield Grammar School, England]

Question: You’ve written biographies of other stars as varied as Abbott and Costello to Paul Robeson, but your introduction makes it quite clear that Boris Karloff holds a very special place for you. What’s your personal favorite of Karloff’s films and has this choice changed over the years?

Scott Allen Nollen: Boris was the first hero I ever had, and every book I’ve written is about one of my heroes who has inspired me for most of my life. My mother is responsible for introducing me to Boris when she asked me to watch Frankenstein on a Saturday night in 1968, when I was just five years old. I understood the Monster. I identified with him, and still do. He’ll always be my favorite cinematic character. I love the poor, misunderstood creature who Boris pointed out, like all of us, “had no say in his creation.”

The Monster is a metaphor for an outcast, a minority being, an underdog, who suffers due to the prejudice that plagues all human beings. After you learn about Boris’ political beliefs (which helped to create the much-needed Screen Actors Guild in 1933), you realize that they’re all there in the speechless Monster. If that’s not genius, I don’t know what is.

I have two favorite Karloff films, because you have to divide them into two categories: the ones in which he wears heavy makeup; and the ones in which he doesn’t. The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) is my favorite in the former category, and The Body Snatcher (1945) is my favorite in the latter. Bride is a towering masterpiece on a myriad of levels, the finest achievement of the great James Whale, one of the most innovative, original filmmakers of all time.

The Body Snatcher is based on a story by Robert Louis Stevenson, my favorite author and a contender for the greatest writer of English prose (his Auld Scots isn’t too bad, either). The incredible thing about this Val Lewton production directed by Robert Wise is that it greatly improves on Stevenson’s short story, which was based on the infamous 1828 Burke and Hare murders in Edinburgh.

Question: I mentioned in my email to you that I love the early parts of film biographies, especially right up to the point where the subject makes it big. What kind of film career do you expect Boris Karloff would have had had he never appeared in Frankenstein?

Scott Allen Nollen: That is really a question impossible to answer, of course, because it requires pure speculation. Considering the fact that he toiled in films for 12 years before Whale chose him to play the Monster, basically because Jimmy was fascinated by Boris’ face, he may just have continued to play character parts, like so many other British actors who migrated to Hollywood. Boris learned his craft working in small stock companies, constantly traveling and playing a vast array of parts, so he had the versatility required for character roles. However, I suspect that, if it wasn’t Frankenstein, perhaps another film could have tapped into his truly unique, natural talent.

Boris was an instinctual actor: He learned his lines and then just went on and “did it.” I asked Julie Harris if there was any “clash of techniques” between her and Boris while preparing for The Lark, because she was trained in “The Method.” She told me that Boris said, “As long as you get there, it doesn’t matter how you get there.” He was exceptionally gifted, so I suspect he would have excelled in another role if the Monster hadn’t come along. However, he was 43 when Whale shot Frankenstein, and we all know about the youth-obsessed culture of Hollywood, and America in general.

So I guess the most truthful answer to the question is that no one will ever know, but I like to think positively about “Dear Boris.”

Frankenstein lives! Harold N. Nollen, the author’s father, takes a snooze with “The Monster” in Boris Karloff’s bed! In 1996, Mr. Nollen accompanied his son on a two-week research trip to California, where they primarily stayed at the Rancho Mirage home of Sara Karloff. The bed was used by Karloff in his Beverly Hills home during the 1930s. [author’s collection]

Question:Regarding Karloff the man. I was struck by his continuing to take almost any job even after he had found success. He’d even mentioned that a working actor should never turn down a job offer. But in A Gentleman’s Life we see that Karloff takes this to extremes such as when Maurice Evans asked for a photo of him in Arsenic and Old Lace so he could model the part on Boris in his own production, yet Karloff offers himself for the part instead of just a photo! And the call from the small production company in Alaska asking him to play that same part, a call that Boris originally thought was a joke, he wound up taking that too! What drove this man to continue working, often through great pain and later advanced age?

Scott Allen Nollen: The complicated, truthful answer is that Evie kept him working. She was really his “unofficial” agent and enjoyed the lifestyle that her husband’s work made possible. She would actually accept parts for him. Why else would be appear, unable to walk and hardly able to breathe, in that dreadful Mexican quartet of horror films, after which he didn’t live long enough to cash the check? But Evie also took very good care of Boris, and helped make it possible for him to have such a lengthy, productive career.

The easy answer is that Boris loved it. He was a working actor. He always said he’d “die with his boots on,” and he very nearly did. He had just finished performing in a television show in the States before he entered the hospital for the final time, after he’d flown back to London.

Evie and Boris, following a successful deep-sea fishing expedition while on holiday in Acapulco, March 1953. Evie enjoyed the globetrotting lifestyle made possible by Boris’ professionalism as a “working actor.” [author’s collection; owned by Boris Karloff; a gift from the late Evelyn Karloff]

Question: Life seems to have changed becoming even busier after Karloff married for the final time. Karloff was in his late 50s when he married Evie, an age you’d think would have him set in his ways, but the pace really picks up after they get together! What kind of impact do you think Evie had on Karloff’s life, especially in comparison to Sara Jane’s mother, Dorothy, who was married to Boris at the time his film career really took off?

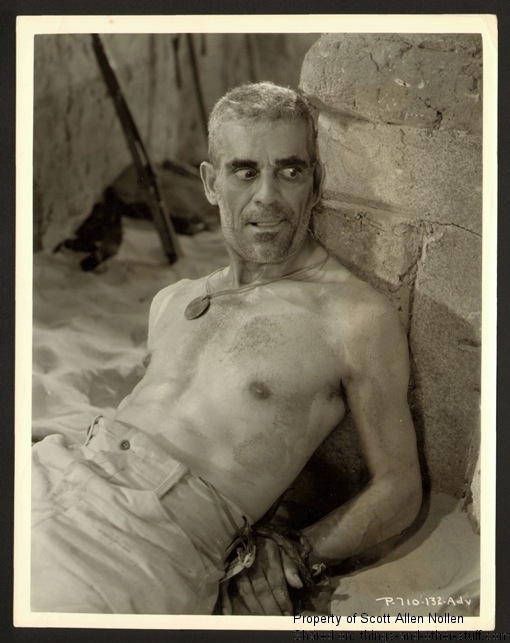

Scott Allen Nollen: Dorothy was married to Boris when he was still fairly young and in really impressive physical condition. Just look at the photos of him taken around the swimming pool at the Beverly Hills home during the late 1930s. (I was able to spend some time there while working on the book, by the way—and the pool, and Boris’ pen for his pet pig, was still there!) He was solid muscle, a fine figure of a man.

By the time Boris married Evie, he was suffering from acute back problems, and then arthritis and emphysema as time went on. He became somewhat dependent on Evie. All of the details about these relationships are carefully revealed in the book (where many such Karloff lingering “mysteries” are solved, due to exhaustive detective work!).

Apparently, the man never complained, no matter how awful he felt or now much pain he suffered.

One of the author’s favorite photos of Boris, this original “beefcake” publicity still for John Ford’s The Lost Patrol (1934), in which Karloff portrays a religious fanatic who goes totally insane in the Mesopotamian desert during World War I, displays the fine physical condition he still enjoyed at age 46. [author’s collection; original studio publicity still]

Evie and Boris, on location in Hawaii during the shooting of Voodoo Island (1956). [author’s collection; Polaroid snapshot owned by Boris Karloff; a gift from the late Evelyn Karloff]

Question: Finally I’d asked you about your favorite Karloff movies and how that choice had evolved. How did your opinion of Karloff the man change as you came to know him so intimately during the writing of A Gentleman’s Life?

Scott Allen Nollen: It didn’t really change. The impression that initially hit me as a child, expressed to me through Karloff’s extraordinarily expressive eyes (necessary tools for a great actor), and then developed further as I earnestly began to study about him as a teenager, was continually reinforced as I researched and wrote both books. Everyone who knew him, worked with him—loved him—had the same things to say about the man. The great character actor Henry Brandon, a straight-shooter who always told it like it was, admitted to me that he saw Boris lose his temper only once—and that was in Rome, when he observed tourists being treated with disrespect.

No matter what Boris did in his career—which included the stage, films, radio, television and spoken-word recordings—or fighting for his colleagues as a pioneering labor organizer in the creation of the Screen Actors Guild, or in the charity and humanitarian work he did, he was first and foremost, a gentleman.

Even though he emerged from the Victorian Era, Boris had a strikingly open mind, was an egalitarian, a visionary,, and referred to himself as a “philosophical anarchist.” He truly was, as the English would say, a “one off.”

I would use the old cliché and say that “they broke the mold” after he arrived on this Earth, but—in Boris’ case—there was no mold to begin with.

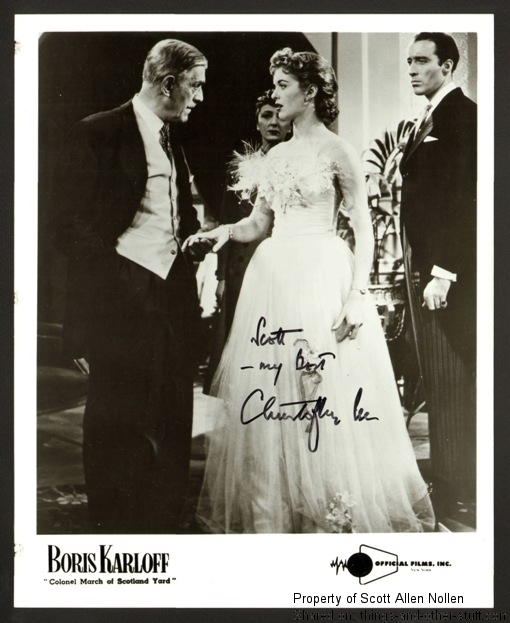

Original publicity still for the March 21, 1956, “At Night All Cats Are Grey” episode of Karloff’s British television series Colonel March of Scotland Yard, signed to the author by Christopher Lee (right). [author’s collection; original studio publicity still]

One of the last formal publicity portraits of Karloff, 1966. [author’s collection; owned by Boris Karloff; a gift from the late Evelyn Karloff]

Handwritten testimonial from the late Vincent Price, sent to the author in 1982. [author’s collection]

Many thanks once more to Scott Allen Nollen for this fantastic contribution to the Immortal Ephemera site.

Mr. Nollen and Mr. Aliperti, thank you for a most pleasant morning sitting in front of the computer, sipping my tea and enjoying talk about the great Karloff.

This interview was DELIGHTFUL!

Wow, to have Nollen’s experience would be a dream come true for those who watch Karloff’s movies and admire the man who made Frankensteins monster our favorite movie character. Although I’ve never thought of his character as a villain for some reason. I am curious what Nollen thought of the film “Gods and Monsters”, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

I’m glad the question was asked regarding Boris continuing to work since his later scripts weren’t up to par with his talent. In doing the snarky review of The Ape recently it pained me to see Karloff in that role. It was so beneath him as a great actor.

Thanks so much for sharing this interview and the wonderful collection of photos. I’ll definitely be adding Mr. Nollen’s book to my collection.

Page

I absolutely adore the film GODS AND MONSTERS, since James Whale is practically one on my “gods!” and you know what I think of the Monster! A beautiful film about a beautiful man. I had the absolute pleasure of writing about “Jimmy” again in my just-published book on Paul Robeson, which includes an entire chapter on the great SHOW BOAT (1936), Jimmy’s favorite of his own films, along with THE INVISIBLE MAN (1933). Ian McKellen should have received the Oscar for his uncanny performance as Whale, although the politics obviously weren’t on his side. (I’ve known people on the Academy, and the truth they’ve told me about how it all works is truly sickening–I’m not the only film scholar who thinks Boris should have won a Best Actor Oscar for THE BODY SNATCHER!) In any event, GODS AND MONSTERS is brilliant, beautiful, and I don’t have time to watch it enough. I have loved James Whale all my life–my first real published piece was on him and the making of FRANKENSTEIN–and while seeing GODS for the first time, I couldn’t actually believe it was real–it was like a dream (come true). Thanks–I’m glad you enjoyed the interview–Scott Allen Nollen

My father, pictured in this interview several times–including in that fantastic shot of him “in bed with the Monster,” died this past Friday, August 19. He was 86 years old, and was able to keep laughing about this incident and SO many other wonderful film-oriented things almost right up until the end. I have appreciated the hundreds of lovely messages I have received from people across the globe–Scott Allen Nollen